Ubu Roi: a Directorial Adventure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture's Ephemeral Practices

____________________ A PATAPHYSICAL READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE ______183 A “PATAPHYSICAL” READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE Mary Vaughan Johnson Virginia Tech The Maison de Verre (1928-32) is a glass-block the general…(It) is the science of imaginary house designed and built by Pierre Chareau solutions...”3 According to Roger Shattuck, in (1883-1950) in collaboration with the Dutch his introduction to Jarry’s Exploits & Opinions architect Bernard Bijvoët and craftsman Louis of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, “(i)f Dalbet for the Dalsace family at 31, rue St. mathematics is the dream of science, ubiquity Guillaume in Paris, France. A ‘pataphysical the dream of mortality, and poetry the dream reading of the Maison de Verre, undoubtedly of speech, ‘pataphysics fuses them into the one of the most powerful modern icons common sense of Dr. Faustroll, who lives all representing modernism’s alliance with dreams as one.” In the chapter dedicated to technology, is intended as an alternative C.V. Boys, Jarry, for instance, with empirical history that will yield new meanings of precision, describes Dr. Faustroll’s bed as modernity. Modernity in architecture is all too being 12 meters long, shaped like an often associated with the constitution of an elongated sieve that is in fact not a bed, but a epoch, a style developed around the turn of boat designed to float on water according to the 20th century in Europe albeit intimately tied Boys’ principles of physics.4 The image of a to its original meaning related to an attitude boat that is also a bed, at the same time, towards the passage of time.1 To be truly brings to mind the poem by Robert Louis modern is to be in the present. -

Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts Paintings, Drawings, Calligrammes

! 44a Charlotte Road, London, EC2A 3PD Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts paintings, drawings, calligrammes 4 November - 16 December 2016 ____________________ Private View: 3 November 6.30 - 8.30 pm Calligramme XXIII (‘fossil’),1961 (?), Black, gold and red paint on paper, 52 x 63.5cm, © Themerson Estate, courtesy of l’étrangère. " It seemed to me that the interrelation between these two sides: order in nature on the one side, and the human condition on the other, was the undefinable drama to be grasped, dealt with and communicated by me. - Franciszka Themerson, Bi-abstract Pictures, 1957 l’étrangère is delighted to present a solo exhibition of paintings, drawings and calligrammes by Franciszka Themerson - a seminal figure in the Polish pre-war avant-garde. She developed her unique pictorial language during the shifting years of pre- and post-war Europe, having settled in Britain in 1943. Together with her husband, writer, poet and filmmaker, Stefan Themerson, she was involved with experimental film and avant-garde publishing. Her personal domain, however, focused on painting, drawing, theatre sets and costume design. This exhibition brings together Franciszka’s three paintings completed in 1972 and a selection of drawings, dated from 1955 to 1986, which demonstrate the breadth of her work. ! The paintings: Piétons Apocalypse, A Person I Know and Coil Totem, act as anchors in the exhibition, while the drawings demonstrate the variety of motifs recurring throughout her work. The act of drawing and the key role of the line remain a constant throughout her practice. The images are characterised by a fluidity of line, rhythmic composition and the humorous depiction of everyday life. -

MD Tour Press Release

Ubu Projex Press Information dated 2/28/11 [email protected] The Annotated Modern Dance Pere Ubu tours Europe in May 2011 with a special program, "The Annotated Modern Dance." The band will perform its seminal debut album in its entirety along with the Hearpen singles that preceded it. Brief anecdotes will precede the songs. "The Modern Dance" was released in February 1978 and stunned the pop and punk worlds with its vision and audac- ity. It quickly became a fixture in Great / Most Influential Albums Of All Time lists. Jon Savage, Sounds, 2/11/78 Uh-oh, this is getting frustrating, trying to tell you how good this is - black and white is an inadequate substitute for the impact heard... This is a brilliant debut. Granted it lacks the superficial accessibility of lesser works, but this time around the aroma lingers. This is built to last! Ubu's world is rarely comfortable, full of the space beyond the electric light and what it does to people, but always direct and unwavering. And courageous. Ian Birch, Melody Maker, 3/18/78 It's a devastating debut...this album has struck me with a vengeance. Because it delivers such a powerful, complex and open-ended punch, it's almost impossible at such an early stage to explain why or how in full detail. David Stubbs, Uncut, August 2006 - 5 Stars Announced by the siren squeal of Allen Ravenstine's analogue synth which launches "Non- Alignment Pact," The Modern Dance is a product of Cleveland, the living model of punk's post-industrial wasteland. -

Download (112Kb)

Deliciously Crazy By Order Of Mayor Pawlicki, Pere Ubu (2CD, Cherry Red) When I interviews David Thomas, lead singer of Pere Ubu, back the end of the 20th Century, he had this to say about gigs: 'We don't like touring. We like the playing but not the driving. We don't like being in the newspaper. We don't have anything to say that anybody wants to hear. We don't care. I think that sums it up.' Mind you, he also said that he 'always thought [Pere Ubu] were a very traditional rock band. No, we are a very traditional rock band and always have been. It's not our fault that others have abandoned their roots and culture and traditions.' If you've heard the lurching, cacophonous monster that is Pere Ubu making music then you will probably be as sceptical as me. Pere Ubu came screaming out of Cleveland Ohio on the tail of American new wave and punk. Desperate to find new things to write about, the UK music press created scenes were there were none, invented fictional success stories and nonsensical controversies, launching a thousand bands they would later torpedo and sink. Some how, Pere Ubu are still afloat on an ocean of ragged vocals, jagged guitar, squawky synthesizers and offbeat rhythms. The press release uses the phrases 'dedicated brutality' which comes pretty close. I love Pere Ubu. They have never sounded like anyone else, have never bowed to peer or critical pressure, and have ploughed their own way through the music industry from the word go. -

The Blank Generation

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Blank Generation (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Akron 1976-80 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The "blank generation" came out of a moral vacuum. While punks roamed the suburban landscape, blue-collar workers were feeling the pinch of an economic revolution: human society had left the industrial age and entered the post-industrial age, the age in which services (such as software) prevail over manufacturing. Computers now rule the world, from Wall Street to Boeing. The assembly line took away a bit of the personality of the worker, but that was nothing: the new service- based economy takes away the worker completely, physically. In the post-industrial society the individual is even less of a "person". The individual is merely a cog in a huge organism of interconnected parts that works at the beat of a gigantic network of computers. This highly sophisticated economy treats the individual as a number, as a statistic. The goal is no longer to create a robot that behaves like a human being, but to create a human being that behaves like a robot: robots are efficient and lead to manageable and profitable businesses, whereas humans are inefficient and difficult to manage. -

Ubu Roi Short FINAL

media contact: erica lewis-finein brightbutterfly[at]hotmail.com CUTTING BALL THEATER CONTINUES 15TH SEASON WITH “UBU ROI” January 24-February 23, 2014 In a new translation by Rob Melrose SAN FRANCISCO (December 16, 2013) – Cutting Ball Theater continues its 15th season with Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI in a new translation by Rob Melrose. Russian director Yury Urnov (Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company) helms this irreverent take on world leaders. Featuring David Sinaiko, Ponder Goddard, Marilet Martinez, Bill Boynton, Nathaniel Justiniano, and Andrew Quick, UBU ROI plays January 24 through February 23 (Press opening: January 30) at the Cutting Ball Theater in residence at EXIT on Taylor (277 Taylor Street) in San Francisco. For tickets ($10-50) and more information, the public may visit cuttingball.com or call 415-525-1205. When Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI premiered in Paris on December 10, 1896, the audience broke into a riot at the utterance of its first word. Jarry’s parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth defies theatrical tradition through its disregard for audience expectations, replacing Shakespeare’s tragic hero with a greedy, sadistic ogre who becomes the King of Poland by force and through the debasement of his people. Set in a modern luxury kitchen, this re-visioned UBU ROI features a wealthy American couple who play out their fantasies of wealth and power to excess as they take on the roles of Mother and Father Ubu. Cutting Ball’s version of UBU ROI may bring to mind the fall from grace of many a contemporary political leader corrupted by power, from Elliot Spitzer to Dominique Strauss-Kahn. -

ABBAYE Livres

GEOFFROY J.-R. et BEQUET Y. S.VV Commissaires-Priseurs Habilités ROYAN, 6, Rue R. Poincaré, (17207 ) Tél: 05.46.38.69.35 -Fax: 05.46.39.28.05 E-mail : [email protected] SAINTES , 38 Bld Guillet-Maillet (Bureau annexe) Tél: 05.46.93.39.14 E-mail : [email protected] ,N° d’agrément 2002-204 VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES Jeudi 7 Décembre à 11h15 (Lots 1 à125) Jeudi 7 Décembre à 14h15 (Lots 125à fin) Abbaye aux Dames 17100 Saintes LIVRES et AUTOGRAPHES Expositions : Mercredi 6 Décembre de 14h à 19h et Jeudi 7 Décembre de 9h à 11h Expert Christine CHATON – 3, rue Gautier – 17100 Saintes Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés (C.N.E.S.) Tél : 06.08.92.27.75 / Fax : 09.81.70.96.13 / [email protected] : LISTE Vente du matin (11h15) 1 1. ALMANACHS & ÉTRENNES. XVIIIe - XIXe s. Réunion d’une trentaine de volumes 250 350 dont : - Le Meilleur Livre ou Les meilleures Etrennes que l’on puisse donner et recevoir. Paris, Prault, 1745. Cart. papier gaufré avec motifs doré. Etat moyen. - Calendrier de la Cour. (1764). In-32, reliure maroquin brun. - Les Spectacles de Paris ou Calendrier … des Théâtres (1770). - Étrennes Intéressantes (1780, An VI, An VIII, 1816), avec étuis. - Étrennes Nouvelles, commodes et utiles, imprimées par ordre de son Eminence Monseigneur le Cardinal de La Rochefoucauld… à l’usage de son diocèse. Rouen, Seyer, 1783. In-16, reliure veau brun (usagée). - Almanach des Muses (1783). In-12, broché. Pas de page de titre. - Calendrier du Limousin (Barbou, 1787). -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I am using the terms ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Michel de Certeau’s sense, in that ‘space is a practiced place’ (Certeau 1988: 117), and where, as Lefebvre puts it, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’ (Lefebvre 1991: 26). Evelyn O’Malley has drawn my attention to the anthropocentric dangers of this theorisation, a problematic that I have not been able to deal with fully in this volume, although in Chapters 4 and 6 I begin to suggest a collaboration between human and non- human in the making of space. 2. I am extending the use of the term ‘ extra- daily’, which is more commonly associated with its use by theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe the per- former’s bodily behaviours, which are moved ‘away from daily techniques, creating a tension, a difference in potential, through which energy passes’ and ‘which appear to be based on the reality with which everyone is familiar, but which follow a logic which is not immediately recognisable’ (Barba and Savarese 1991: 18). 3. Architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton distinguishes between the ‘sceno- graphic’, which he considers ‘essentially representational’, and the ‘architec- tonic’ as the interpretation of the constructed form, in its relationship to place, referring ‘not only to the technical means of supporting the building, but also to the mythic reality of this structural achievement’ (Frampton 2007 [1987]: 375). He argues that postmodern architecture emphasises the scenographic over the architectonic and calls for new attention to the latter. However, in contemporary theatre production, this distinction does not always reflect the work of scenographers, so might prove reductive in this context. -

REFASHIONING the FIGURE the Sketchbooks of Archipenko C.1920

41 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920 Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture MAREK BARTELIK 2 3 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.19201 MAREK BARTELIK Anyone who cannot come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate…but with his other hand he can note down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different (and more) things than the others: after all, he is dead in his own lifetime, he is the real survivor.2 Franz Kafka, Diaries, entry on 19 October 1921 The quest for paradigms in modern art has taken many diverse paths, although historians have underplayed this variety in their search for continuity of experience. Since artists in their studios produce paradigms which are then superseded, the non-linear and heterogeneous development of their work comes to define both the timeless and the changing aspects of their art. At the same time, artists’ experience outside of their workplace significantly affects the way art is made and disseminated. The fate of artworks is bound to the condition of displacement, or, sometimes misplacement, as artists move from place to place, pledging allegiance to the old tradition of the wandering artist. What happened to the drawings and watercolours from the three sketchbooks by the Ukrainian-born artist Alexander Archipenko presented by the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a poignant example of such a fate. Executed and presented in several exhibitions before the artist moved from Germany to the United States in the early 1920s, then purchased by a private collector in 1925, these works are now being shown to the public for the first time in this particular grouping. -

Mise En Page 1

BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. EDITIONSORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHESET MANUSCRITSDU XX E SIÈCLE MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 - SOTHEBY’S PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 Experts de la vente DOMINIQUE COURVOISIER Expert de la Bibliothèque nationale de France Membre du Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en œuvres d’art 5, rue de Miromesnil 75008 Paris Tél./Fax. + 33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 [email protected] ANNE HEILBRONN SOTHEBY’S 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré 75008 Paris Tél. +33 (0)1 53 05 53 18 Fax. +33 (0)1 53 05 52 23 [email protected] Tous nos remerciements à Monsieur Jean-Paul Goujon pour l’aide précieuse apportée à la rédaction des notices des manuscrits et des autographes MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 À 14H30 VENTE À PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHES ET MANUSCRITS DU XXE SIÈCLE Vente dirigée par Cyrille Cohen et Alexandre Giquello Agréments du Conseil des Ventes Volontaires de Meubles aux Enchères Publiques n° 2001-002 et n° 2002-389 EXPOSITION Vendredi 3 et samedi 4 octobre de 10h à 18h Lundi 6 octobre de 10h à 20h sothebys.com/bidnow 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré - 75008 Paris tél. 33 (0)1 53 05 53 05 www.sothebys.com SPÉCIALISTES RESPONSABLES DE LA VENTE Pour toute information complémentaire concernant les lots de cette vente, veuillez contacter les experts listés ci-dessous. RÉFÉRENCE DE LA VENTE ENCHÈRES TÉLÉPHONIQUES PF1453 “Médaillon” & ORDRES D’ACHAT +33 (0)1 53 05 53 48 Fax +33 (0)1 53 05 52 93/94 EXPERTS DE LA VENTE [email protected] Dominique Courvoisier Les demandes d’enchères +33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 téléphoniques doivent nous [email protected] parvenir 24 heures avant la vente. -

By William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why Give

Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why give Welcome to our 2015 season with Measure for Measure. you me this Our Russian company were last here with The Tempest and we are delighted to be back. We are particularly grateful to shame? Evgeny Pisarev and Anna Volk of the Pushkin Theatre in Moscow, without whom this production would not have been possible. Act III Scene I Thanks also to Toni Racklin, Leanne Cosby, and the entire team at the Barbican, London for their continued enthusiasm and support, and to Katy Snelling and Louise Chantal at the Oxford Playhouse. We’d also like to thank our other co-producers, Les Gémeaux/ Sceaux/Scène Nationale, in Paris, and Centro Dramático Nacional, in Madrid, as well as Arts Council England. We do hope you enjoy the show… Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod Petr Rykov & Company 1 2 3 Cheek by Jowl in Russia In 1986, Russian theatre director Lev Dodin of Valery Shadrin, commissioned Donnellan invited Donnellan and Ormerod to visit his and Ormerod to form their own company of company in Leningrad. Ten years later, they Russian actors in Moscow. This sister company 4 5 6 directed and designed The Winter’s Tale performs in Russia and internationally and its for the Maly Drama Theatre, which is still current repertoire includes Boris Godunov running in St. Petersburg. Throughout the by Pushkin, Twelfth Night and The Tempest 1990s the Russian Theatre Confederation by Shakespeare, and Three Sisters by Anton regularly invited Cheek by Jowl to Moscow Chekhov. Measure for Measure is Cheek as part of the Chekhov International Theatre by Jowl’s first co-production with Moscow’s Festival, and this relationship intensified in Pushkin Theatre. -

Pere Ubu Stage Plot 7/4/2

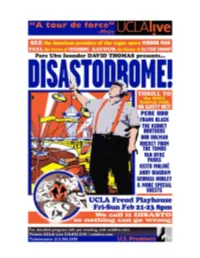

What is Disastodrome? Disastodrome is a three day festival of voice and vision where the reputations of 18 avant-garage heroes will be collectively tested. These boundary-breakers, forever outside the world of music-by-numbers, are led by Pere Ubu founder, David Thomas. David Thomas is "one of America's most enigmatic and visionary talents" and a vocalist of genuine originality. His avant-rock group Pere Ubu is a byword for the uncompromising pursuit of musical vision. His improvisational trio, David Thomas and two pale boys, is the latest in a line of pop experiments intent on rewriting the rules of music production. He has collaborated with musicians of all sorts from the steppes of Siberia to the canals of Manchester, lectured at universities and art centers on "The Geography of Sound in the Magnetic Age" and, in 2002, starred in the West End production of "Shockheaded Peter." Disastodrome 2003, staged at the Freud Playhouse, UCLA, Los Angeles, February 21-23, 2003, and produced by UCLA Live, includes live performances from Pere Ubu, Frank Black, and The Kidney Brothers, as well as the first appearance in 27 years of the legendary Rocket From The Tombs and the American premiere of David Thomas' rogue opera, Mirror Man. The festival will be hosted by Johnny Dromette, creator of the original datapanik range of goods and services, and will feature a variety of lobby events, displays and motivational apparatus items called Foyerdrome, one component of which is the roving Voices From The Fringe, delivered by neo-beat poet Bob Holman. The early Disastodromes (1977-78) were staged at a radio theater in a broken part of Cleveland and featured burst steam pipes, flaming sofas and voice-of-doom winos lurking in all the dark corners.