2. Thomas Aquinas on Conscience. 33 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

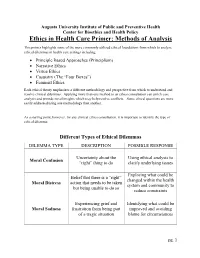

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

Early Medieval G

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2001 History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval G. Scott aD vis University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, G. Scott. "History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval." In Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker, 709-15. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, 2001. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval Copyright 2001 from Encyclopedia of Ethics by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis, LLC, a division of Informa plc. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval ''Medieval" and its cognates arose as terms of op probrium, used by the Italian humanists to charac terize more a style than an age. Hence it is difficult at best to distinguish late antiquity from the early middle ages. It is equally difficult to determine the proper scope of "ethics," the philosophical schools of late antiquity having become purveyors of ways of life in the broadest sense, not clearly to be distin guished from the more intellectually oriented ver sions of their religious rivals. This article will begin with the emergence of philosophically informed re flection on the nature of life, its ends, and respon sibilities in the writings of the Latin Fathers and close with the twelfth century, prior to the systematic reintroduction and study of the Aristotelian corpus. -

NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, and the FUNCTION of CONSCIENCE in THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan –

Diametros 47 (2016): 1–18 doi: 10.13153/diam.47.2016.865 NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, AND THE FUNCTION OF CONSCIENCE IN THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan – Abstract. Both the function of one’s conscience, as Thomas Aquinas understands it, and the work of casuistry in general involve deliberating about which universal moral principles are applicable in particular cases. Thus, understanding how conscience can function better also indicates how casuistry might be done better – both on Thomistic terms, at least. I claim that, given Aquinas’ de- scriptions of certain parts of prudence (synesis and gnome) and the role of moral virtue in practical knowledge, understanding particular cases more as narratives, or parts of narratives, likely will result, all else being equal, in more accurate moral judgments of particular cases. This is especially important in two kinds of cases: first, cases in which Aquinas recognizes universal moral principles do not specify the means by which they are to be followed; second, cases in which the type-identity of an action – and thus the norms applicable to it – can be mistaken Keywords: Thomas Aquinas, conscience, narrative, casuistry, prudence, virtue, moral judgment, moral development, moral knowledge. Introduction ‘Casuistry’ has a bad reputation in some circles. It tends to be associated wi- th formalized, but too legalistic, approaches to determining and enumerating mo- ral faults. In a more generic sense, though, casuistry just refers to deliberating about and discerning what universal moral principles apply in particular cases, based on relevant details of the case at issue. As Thomas Aquinas understands things, casuistry parallels the ordinary, everyday function of one’s conscience, which specifically regards particular cases in which one deliberates about one’s own morally relevant actions.1 Given this, we might be able to gain insight to how formalized casuistry can be done well by drawing an analogy from what it takes for conscience to function well. -

Health Care Ethics and Casuistry

Jrournal ofmedical ethics, 1992, 18, 61-62, 66 J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.18.2.61 on 1 June 1992. Downloaded from Guest editorial: A personal view Health care ethics and casuistry Robin Downie University ofGlasgow In an editorial (1) Dr Gillon looks at some recent method of teaching and discussing medical ethics. The difficulties which have been raised about philosophy answer to Smith here is to point out that what is taking and the teaching ofhealth care ethics. This matter is of place in such discussions is a form of what he calls sufficient importance to the readers of this journal that 'natural jurisprudence'. It is an attempt to translate it is worth looking at it again, this time in an historical into case law, to give concrete application to, the ideals perspective. contained in codes. If natural jurisprudence is a One claim which is often made by those advocating legitimate activity, so too is this. the study of health care ethics is that such a study will Smith's second group ofarguments against casuistry assist in the solving of what have come to be called are to the effect that it does not 'animate us to what is 'ethical dilemmas'. Since health care ethics is so widely generous and noble' but rather teaches us 'to chicane taught for this reason the claim is worth examining. Is with our consciences' (4). Smith is certainly correct in health care ethics in this sense possible? Is it desirable? claiming that casuistry is concerned mainly with whatcopyright. Is it philosophy? In other words, can a case be made out is required or forbidden, that is, with rules, rather than for what earlier centuries called 'casuistry, or the with questions of motivation. -

The New Casuistry

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers April 1999 The ewN Casuistry Paul R. Tremblay Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Paul R. Tremblay. "The eN w Casuistry." Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 12, no.3 (1999): 489-542. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New Casuistry PAUL R. TREMBLAY* Of one thing we may be sure. If inquiries are to have substantialbasis, if they are not to be wholly in the air the theorist must take his departurefrom the problems which men actually meet in their own conduct. He may define and refine these; he may divide and systematize; he may abstract the problemsfrom their concrete contexts in individual lives; he may classify them when he has thus detached them; but ifhe gets away from them, he is talking about something his own brain has invented, not about moral realities. John Dewey and James Tufts' [A] "new casuistry" has appearedin which the old "method of cases" has been revived.... 2 Hugo Adam Bedau I. PRACTICING PHILOSOPHY Let us suppose, just for the moment, that "plain people ' 3 care about ethics, that they would prefer, everything else being equal, to do the right thing, or to lead the good life. -

The Ethics of Armed Conflict John W

THE ETHICS OF ARMED CONFLICT JOHN W. LANGO JOHN W. THE ETHICS OF Cover image: photograph by the author of a burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia) standing beside a burrow amidst vegetation at the end of a beach in Ventura, California. Cover design: www.paulsmithdesign.com ISBN 978-0-7486-4574-9 ARMED CONFLICT A COSMOPOLITAN JUST WAR THEORY www.euppublishing.com JOHN W. LANGO THE ETHICS OF ARMED CONFLICT The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 1 09/12/2013 12:10:04 The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 2 09/12/2013 12:10:04 THE ETHICS OF ARMED CONFLICT A Cosmopolitan Just War Theory John W. Lango The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 3 09/12/2013 12:10:04 For my son, sister, mother, and father © John W. Lango 2014, under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives licence Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Times by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4575 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 4576 3 (webready PDF) The right of John W. Lango to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 4 09/12/2013 12:10:04 CONTENTS Preface vii 1 Introduction 1 2 Just War Theory 18 3 Moral Theory 48 4 Theory of Action 77 5 Just Cause 107 6 Last Resort 134 7 Last Resort and Noncombatant Immunity 156 8 Proportionality and Authority 178 9 All Things Considered 200 References 225 Index 239 The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 5 09/12/2013 12:10:04 The Ethics of Armed Conflict.indd 6 09/12/2013 12:10:04 PREFACE During the Cold War, I was startled awake when the ground shook, frightened that nuclear war had begun; but it was Los Angeles, and only an earthquake. -

Reflection and Particulars: Does Casuistry Offer Us Stable Beliefs About Ethics?

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1991 Reflection and arP ticulars: Does Casuistry Offer Us Stable Beliefs about Ethics? David J. Zacker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Zacker, David J., "Reflection and arP ticulars: Does Casuistry Offer Us Stable Beliefs about Ethics?" (1991). Master's Theses. 1004. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1004 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REFLECTION AND PARTICULARS: DOES CASUISTRY OFFER US STABLE BELIEFS ABOUT ETHICS? by David J. Zacker A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Philosophy Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1991 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. REFLECTION AND PARTICULARS: DOES CASUISTRY OFFER US STABLE BELIEFS ABOUT ETHICS? David J. Zacker, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1991 This enquiry suggests a solution to a challenge posed by Bernard Williams (1985) in Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy to develop a positive ethical theory that fulfills his guidelines. In particular, the theory is used to solve two problems: (1) reflection typically uproots and destroys ethical beliefs, and (2) modem ethical theories typically answer questions about ethics universally and ignore their practical characteristics. -

The Political Theology of David Hume

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Political Theology of David Hume A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Philosophy Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan H. Krause Washington, D.C. 2015 The Political Theology of David Hume Jonathan H. Krause, Ph.D. Director: John McCarthy, Ph.D. Hume’s concern for religion is evidenced by his references to it throughout his works. Indeed, he claims in the Natural History that “every enquiry, which regards religion, is of the utmost importance.” Commentators have often treated Hume’s interest in religion as theoretical, as though he was primarily concerned to establish religion’s truth or falsity. Yet in the Essays and History of England he indicates that disputes over religious forms and beliefs are “frivolous” and “utterly absurd.” This raises an obvious question: if disagreements concerning religion are “frivolous” and “absurd,” then why are inquiries regarding religion of “the utmost importance”? Hume’s answer is political in nature. “Religion,” he says in the History, “can never be deemed a point of small consequence in civil government.” He there calls our attention to religious disputes not on detached theoretical grounds, but “only so far as they have influence on the peace and order of civil society.” This dissertation argues that the way to approach Hume on religion is through his understanding of the relationship between religion and political life, that is to say, through his “political theology.” To bring out different aspects of the political problem of religion, each of this dissertation’s four chapters focuses on the textual analysis of a particular work: A Treatise of Human Nature, The Natural History of Religion, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, and The History of England. -

Conceptual Foundations of Bioethics

Monica (wife): We need to think about David’s wishes. He was CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATIONS OF always in control of his life, always a part of every medical decision. His advance directive is very clear. He does not want BIOETHICS: OVERVIEW his life to be artificially extended. We need to tell Dr. Alderfer to Although bioethics has been around for more than four turn off the respirator. decades, the field of neuroethics is in its infancy. Philosophers Amy (sister #2): Just pull the plug? Can Dr. Alderfer do that? I have developed several conceptual frameworks that contain can’t believe that someone can be killed just because the right valuable insights concerning the analysis of questions of right areas don’t light up on a brain scan. I want to hear about how other patients have been treated, why some are left on a respira- and wrong, good and bad. These ethical theories can help us tor while others are removed. There must be some guidelines as as we struggle with the moral dilemmas presented to us by to how to proceed in cases like this. advances in brain science. In the sections that follow, a variety Ben (brother): I think we need to meet with Dr. Alderfer. Amy’s of theories and methods will be explained with reference to point is well taken. We haven’t been in this situation before; we the hypothetical scenario described below.. need some guidance. Before the meeting, however, I want us all to think about what the Cleavers have stood for, we want our actions to reflect the kind of people we are. -

Casuistry and Social Category Bias

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 2004 by the American Psychological Association 2004, Vol. 87, No. 6, 817–831 0022-3514/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.817 Casuistry and Social Category Bias Michael I. Norton Joseph A. Vandello Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of South Florida John M. Darley Princeton University This research explored cases where people are drawn to make judgments between individuals based on questionable criteria, in particular those individuals’ social group memberships. We suggest that indi- broadly. viduals engage in casuistry to mask biased decision making, by recruiting more acceptable criteria to justify such decisions. We present 6 studies that demonstrate how casuistry licenses people to judge on publishers. the basis of social category information but appear unbiased—to both others and themselves—while doing so. In 2 domains (employment and college admissions decisions), with 2 social categories (gender allied and race), and with 2 motivations (favoring an in-group or out-group), the present studies explored how disseminated its participants justify decisions biased by social category information by arbitrarily inflating the relative be of to value of their preferred candidates’ qualifications over those of competitors. one not or is and A male bank president is faced with hiring a new vice president ence. On the other hand, our bank president may feel that it is user in this traditionally male-dominated profession. Two finalists appropriate to give the edge to the woman to make up for tradi- Association emerge: a woman with a great deal of experience but mediocre tional underrepresentation. -

Of Monsters Unleashed: a Modest Beginning to a Casuistry of Cloning

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 32 Number 2 Spring 1998 pp.419-431 Spring 1998 Of Monsters Unleashed: A Modest Beginning to a Casuistry of Cloning Catharine Cookson Emily Ramsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Catharine Cookson and Emily Ramsey, Of Monsters Unleashed: A Modest Beginning to a Casuistry of Cloning, 32 Val. U. L. Rev. 419 (1998). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol32/iss2/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Cookson and Ramsey: Of Monsters Unleashed: A Modest Beginning to a Casuistry of Cloni OF MONSTERS UNLEASHED: A MODEST BEGINNING TO A CASUISTRY OF CLONING CATH JUNE COOKSON* If an educated man is armed with only reason, if he is disdainful of custom and ignores strength offeeling, if he thinks of "prejudice"and "intolerance" as words with no connotations that are not disgraceful and is blind to religious conviction, he had better not venture outside his academy, for if he does he will have to deal with forces he cannot understand.' Fear. Horror. Hunger for glory. The driving urge to create and to discover. These passions, and more, dominate the moral debate over cloning, and we ignore them at our peril. The challenge is how to take due account of the feelings and images that swirl around this issue, while not letting them dominate the public discourse.