A Historical Perspective of Casuistry and Its Application to Contemporary Biomedical Ethics Alexander J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

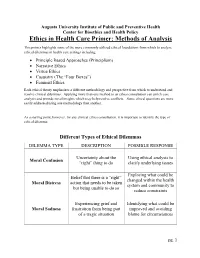

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

Philosophy and the Art of Living Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel

Philosophy and the Art of Living Osher Life-Long Learning Institute (UC Irvine) 2010 The Masters of Reason and the Masters of Suspicion: Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre When: Mondays for six weeks: November 1 ,8, 15, 22, 29, and Dec. 6. Where: Woodbridge Center, 4628 Barranca Pkwy. Irvine CA 92604 NOTES AND QUOTES: Aristotle: 384 BCE- 322 BCE (62 years): Reference: http://www.jcu.edu/philosophy/gensler/ms/arist-00.htm Theoretical Reason contemplates the nature of Reality. Practical Reason arranges the best means to accomplish one's ends in life, of which the final end is happiness. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-ethics/#IntVir Aristotle distinguishes two kinds of virtue (1103a1-10): those that pertain to the part of the soul that engages in reasoning (virtues of mind or intellect), and those that pertain to the part of the soul that cannot itself reason but is nonetheless capable of following reason (ethical virtues, virtues of character). Intellectual virtues are in turn divided into two sorts: those that pertain to theoretical reasoning, and those that pertain to practical thinking 1139a3-8). He organizes his material by first studying ethical virtue in general, then moving to a discussion of particular ethical virtues (temperance, courage, and so on), and finally completing his survey by considering the intellectual virtues (practical wisdom, theoretical wisdom, etc.). Life : Aristotle was born in northern Greece in 384 B.C. He was raised by a guardian after the death of his father, Nicomachus, who had been court physician to the king of Macedonia. Aristotle entered Plato's Academy at age 17. -

Contradiction and Aporia in Early Greek Philosophy John Palmer

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11015-1 — The Aporetic Tradition in Ancient Philosophy Edited by George Karamanolis , Vasilis Politis Excerpt More Information chapter 1 Contradiction and Aporia in Early Greek Philosophy John Palmer An aporia is, essentially, a point of impasse where there is puzzlement or perplexity about how to proceed. Aporetic reasoning is reasoning that leads to this sort of impasse, and an aporia-based method would be one that centrally employs such reasoning. One might describe aporia, more basically, as a point where one does not know how to respond to what is said. In the Platonic dialogues dubbed ‘aporetic’, for instance, Socrates brings his interlocutors to the point where they no longer know what to say. Now, it should be obvious that there was a good deal of aporetic reasoning prior to Socrates. It should also be obvious that the form of such reasoning is immaterial so long as it leads to aporia. In particular, the reasoning that leads to an aporia need not take the form of a dilemma. Instances of reasoning generating genuine dilemmas – with two equally unpalatable alternatives presented as exhausting the possibilities – are actually rather rare in early Greek philosophy. Moreover, there need not in fact be any reasoning or argumentation as such to lead an auditor to a point where it is unclear how to proceed or what to say. Logical paradoxes such as Eubulides’ liar do not rely on argumentation at all but on the exploitation of certain logical problems to generate an aporia. All that is required in this instance is the simple question: ‘Is what a man says true or false when he says he is lying?’ It is hard to know how to answer this question because any simple response snares one in contradiction. -

Early Medieval G

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2001 History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval G. Scott aD vis University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, G. Scott. "History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval." In Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker, 709-15. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, 2001. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval Copyright 2001 from Encyclopedia of Ethics by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis, LLC, a division of Informa plc. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval ''Medieval" and its cognates arose as terms of op probrium, used by the Italian humanists to charac terize more a style than an age. Hence it is difficult at best to distinguish late antiquity from the early middle ages. It is equally difficult to determine the proper scope of "ethics," the philosophical schools of late antiquity having become purveyors of ways of life in the broadest sense, not clearly to be distin guished from the more intellectually oriented ver sions of their religious rivals. This article will begin with the emergence of philosophically informed re flection on the nature of life, its ends, and respon sibilities in the writings of the Latin Fathers and close with the twelfth century, prior to the systematic reintroduction and study of the Aristotelian corpus. -

NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, and the FUNCTION of CONSCIENCE in THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan –

Diametros 47 (2016): 1–18 doi: 10.13153/diam.47.2016.865 NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, AND THE FUNCTION OF CONSCIENCE IN THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan – Abstract. Both the function of one’s conscience, as Thomas Aquinas understands it, and the work of casuistry in general involve deliberating about which universal moral principles are applicable in particular cases. Thus, understanding how conscience can function better also indicates how casuistry might be done better – both on Thomistic terms, at least. I claim that, given Aquinas’ de- scriptions of certain parts of prudence (synesis and gnome) and the role of moral virtue in practical knowledge, understanding particular cases more as narratives, or parts of narratives, likely will result, all else being equal, in more accurate moral judgments of particular cases. This is especially important in two kinds of cases: first, cases in which Aquinas recognizes universal moral principles do not specify the means by which they are to be followed; second, cases in which the type-identity of an action – and thus the norms applicable to it – can be mistaken Keywords: Thomas Aquinas, conscience, narrative, casuistry, prudence, virtue, moral judgment, moral development, moral knowledge. Introduction ‘Casuistry’ has a bad reputation in some circles. It tends to be associated wi- th formalized, but too legalistic, approaches to determining and enumerating mo- ral faults. In a more generic sense, though, casuistry just refers to deliberating about and discerning what universal moral principles apply in particular cases, based on relevant details of the case at issue. As Thomas Aquinas understands things, casuistry parallels the ordinary, everyday function of one’s conscience, which specifically regards particular cases in which one deliberates about one’s own morally relevant actions.1 Given this, we might be able to gain insight to how formalized casuistry can be done well by drawing an analogy from what it takes for conscience to function well. -

Nietzsche's Platonism

CHAPTER 1 NIETZSCHE’S PLATONISM TWO PROPER NAMES. Even if modified in form and thus conjoined. As such they broach an interval. The various senses of this legacy, of Nietzsche’s Platonism, are figured on this interval. The interval is gigantic, this interval between Plato and Nietzsche, this course running from Plato to Nietzsche and back again. It spans an era in which a battle of giants is waged, ever again repeating along the historical axis the scene already staged in Plato’s Sophist (246a–c). It is a battle in which being is at stake, in which all are exposed to not being, as to death: it is a gigantomac√a p'r¥ t›V o¶s√aV. As the Eleatic Stranger stages it, the battle is between those who drag every- thing uranic and invisible down to earth, who thus define being as body, and those others who defend themselves from an invisible po- sition way up high, who declare that being consists of some kind of intelligibles (nohtº) and who smash up the bodies of the others into little bits in their l¬goi, philosophizing, as it were, with the hammer of l¬goV. Along the historical axis, in the gigantic interval from Plato to Nietzsche, the contenders are similarly positioned for the ever re- newed battle. They, too, take their stance on one side or the other of the interval—again, a gigantic interval—separating the intelligible from the visible or sensible, t¿ noht¬n from t¿ aÎsqht¬n. Those who station themselves way up high are hardly visible from below as they wield their l¬goi and shield themselves by translating their very position into words: m'tΩ tΩ fusikº. -

Charles S. Peirce's Conservative Progressivism

Charles S. Peirce's Conservative Progressivism Author: Yael Levin Hungerford Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107167 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2016 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Charles S. Peirce’s Conservative Progressivism Yael Levin Hungerford A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Boston College Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences Graduate School June 2016 © copyright 2016 Yael Levin Hungerford CHARLES S. PEIRCE’S CONSERVATIVE PROGRESSIVISM Yael Levin Hungerford Advisor: Nasser Behnegar My dissertation explores the epistemological and political thought of Charles S. Peirce, the founder of American pragmatism. In contrast to the pragmatists who followed, Peirce defends a realist notion of truth. He seeks to provide a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge that does justice to our commonsense experience of things. Similarly in contrast to his fellow pragmatists, Peirce has a conservative practical teaching: he warns against combining theory and practice out of concern that each will corrupt the other. The first three chapters of this dissertation examine Peirce’s pragmatism and related features of his thought: his Critical Common-Sensism, Scholastic Realism, semeiotics, and a part of his metaphysical or cosmological musings. The fourth chapter explores Peirce’s warning that theory and practice ought to be kept separate. The fifth chapter aims to shed light on Peirce’s practical conservatism by exploring the liberal arts education he recommends for educating future statesmen. -

Read Article

Title: "Not Buying in to Words and Letters: Zen, Ideology, and Prophetic Critique" Author: Christopher Ives Word length: 2515 Date of Submission: May 2, 2006 Professional Address: Department of Religious Studies, Stonehill College, 320 Washington Street, Duffy 257, Easton, MA 02357-4010 Email: [email protected] Phone: 508-565-1354 Abstract: Judging from the active participation of Zen leaders and institutions in modern Japanese imperialism, one might conclude that by its very nature Zen succumbs easily to ideological co-optation. Several facets of Zen epistemology and institutional history support this conclusion. At the same time, a close examination of Zen theory and praxis indicates that the tradition does possess resources for resisting dominant ideologies and engaging in ideology critique. Not Buying in to Words and Letters: Zen, Ideology, and Prophetic Critique D.T. Suzuki once proclaimed that Zen is "extremely flexible in adapting itself to almost any philosophy and moral doctrine" and "may be found wedded to anarchism or fascism, communism or democracy, atheism or idealism, or any political or economic dogmatism."1 Scholars have recently delineated how, in the midst of Japan's expansionist imperialism, Zen exhibited that flexibility in "adapting itself" and 1 becoming "wedded" to the reigning imperial ideology. And for all of its rhetoric about "not relying on words and letters" and functioning compassionately as a politically detached, iconoclastic religion, Zen has generally failed to criticize ideologies—and specific social and political conditions—that stand in tension with core Buddhist values. Several facets of Zen may account for its ideological co-optation before and during WWII. -

Health Care Ethics and Casuistry

Jrournal ofmedical ethics, 1992, 18, 61-62, 66 J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.18.2.61 on 1 June 1992. Downloaded from Guest editorial: A personal view Health care ethics and casuistry Robin Downie University ofGlasgow In an editorial (1) Dr Gillon looks at some recent method of teaching and discussing medical ethics. The difficulties which have been raised about philosophy answer to Smith here is to point out that what is taking and the teaching ofhealth care ethics. This matter is of place in such discussions is a form of what he calls sufficient importance to the readers of this journal that 'natural jurisprudence'. It is an attempt to translate it is worth looking at it again, this time in an historical into case law, to give concrete application to, the ideals perspective. contained in codes. If natural jurisprudence is a One claim which is often made by those advocating legitimate activity, so too is this. the study of health care ethics is that such a study will Smith's second group ofarguments against casuistry assist in the solving of what have come to be called are to the effect that it does not 'animate us to what is 'ethical dilemmas'. Since health care ethics is so widely generous and noble' but rather teaches us 'to chicane taught for this reason the claim is worth examining. Is with our consciences' (4). Smith is certainly correct in health care ethics in this sense possible? Is it desirable? claiming that casuistry is concerned mainly with whatcopyright. Is it philosophy? In other words, can a case be made out is required or forbidden, that is, with rules, rather than for what earlier centuries called 'casuistry, or the with questions of motivation. -

Nietzsche's Ethic

Nietzsche’s Ethic: Virtues for All and None? A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Daniel Robinson May 2015 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Daniel Robinson B.A., University of South Alabama, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Linda Williams, Associate Professor, Masters Advisor Deborah Barnbaum, Chair, Department of Philosophy James Blank, Associate Dean, Dean of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………….……………......01 Chapter I. Solomon’s Nietzsche: A Summary………………….………….....04 Introduction…………………………………..………...………….04 Concern for Character …………………………………………….05 Passion as the Root to the Virtues…………………………..……..15 Building Nietzsche’s Ethic: Virtues for All……………….….…...22 II. Nietzsche on Ethics……………………………………...……..….32 Introduction………………………………………………………..32 Custom & Natural Morality……………………………………….35 Master-type and Slave-type Moralities…………………………...41 Slave-type’s Universalization ……………………………………48 Nietzsche on Virtue and Virtues …………………….……………52 III. Ethical Contortions: Fitting Nietzsche into Virtue Ethics……...…59 Introduction…………………………………………………….…59 Against a Prescriptive Interpretation……………………….….….60 Redefining Virtue and Ethics……………………………….….…64 Nietzsche’s Individualism …………………………………..…....74 Relevant Bibliography…………………………………………………………….83 i Introduction A year ago I read Robert Solomon’s Living with Nietzsche: What the Great “Immoralist” Has to Teach Us for the first time with the hopes of finding a greater understanding of both Nietzsche and virtue ethics. I was undecided on whether Nietzsche was a virtue ethicist, but I was considering it, simply because of how frequently he mentions virtue and because Aristotle was one of the few major philosophers I knew of that Nietzsche didn’t routinely, vehemently reject. The beginning and middle of Solomon’s text made me very hopeful for his conclusion. -

The Fragments of the Poem of Parmenides

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM: ESSAYS TOWARD A NEW ARRANGEMENT OF THE FRAGMENTS BASED ON A REASSESSMENT OF THE ORIGINAL SOURCES by Christopher John Kurfess B.A., St. John’s College, 1995 M.A., St. John’s College, 1996 M.A., University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, 2000 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Christopher J. Kurfess It was defended on November 8, 2012 and approved by Dr. Andrew M. Miller, Professor, Department of Classics Dr. John Poulakos, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Dr. Mae J. Smethurst, Professor, Department of Classics Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Edwin D. Floyd, Professor, Department of Classics ii Copyright © by Christopher J. Kurfess 2012 iii RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM Christopher J. Kurfess, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 The history of philosophy proper, claimed Hegel, began with the poem of the Presocratic Greek philosopher Parmenides. Today, that poem is extant only in fragmentary form, the various fragments surviving as quotations, translations or paraphrases in the works of better-preserved authors of antiquity. These range from Plato, writing within a century after Parmenides’ death, to the sixth-century C.E. commentator Simplicius of Cilicia, the latest figure known to have had access to the complete poem. Since the Renaissance, students of Parmenides have relied on collections of fragments compiled by classical scholars, and since the turn of the twentieth century, Hermann Diels’ Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, through a number of editions, has remained the standard collection for Presocratic material generally and for the arrangement of Parmenides’ fragments in particular.