The Turn of the Century Are the Years of Devlopment, Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnami Tanulmányútjának Összefoglaló Kiadványa

a Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem Építészmérnöki Kar, Építőművészeti Doktori Iskola vietnami tanulmányútjának összefoglaló kiadványa 2016. 01. 07. - 2016. 01. 17. Vietnam a Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem Építészmérnöki Kar, Építőművészeti Doktori Iskola vietnami tanulmányútjának összefoglaló kiadványa 2016. 01. 07. - 2016. 01. 17. Szervező csapat: Balázs Marcell Biri Balázs Bordás Mónika Molnár Szabolcs Giap Thi Minh Trang A Doktori Iskola vezetője: Balázs Mihály DLA A Doktori Iskola titkárai: Nagy Márton DLA egyetemi adjunktus Szabó Levente DLA egyetemi adjunktus Együttműködők, támogatók: Nemzeti Kulturális Alap Hanoi Építészeti Egyetem Építészmérnöki Kar Budapesti Műszaki Egyetem Kiadvány Szövegek szerkesztése: Kerékgyártó Béla Kiadvány szerkesztése: Beke András Lassu Péter Molnár Szabolcs Tóth Gábor Rajzok: Ónodi Bettina Fotók: A tanulmányút résztvevői BME Építőművészeti Doktori Iskola, 2016 ISBN 978-963-313-222-7 Tartalomjegyzék Előhang (Beke András) Megjelenés Beszámoló Üdv Vietnamnak! (Török Bence) 1 | 10 Konferencia Konferencia a HAU egyetemen Opening speech (Le Quan) 2 | 15 Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem Építészmérnöki Kar (Nagy Márton) The Doctoral School of Architecture at the Faculty of Architecture of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (Szabó Levente DLA) Hungary - (Vasáros Zsolt) Budapest - Built and Cultural environment (Szabó Árpád) Social housing for low-income people in hanoi – current situation and solutions (Khuat Tan Hung) Revitalization of Újpest Central -

The Case of Chinese Entrepreneurs in The

Why Would We Need A “Chinatown”? The case of Chinese entrepreneurs in the rust belts of the 8th and 10th districts of Budapest By MELINDA SZABÓ Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Supervisors Professor Ayse Caglar CEU eTD Collection Assistant Professor Daniel Monterescu Budapest, Hungary 2009 Abstract Although the number of Chinese immigrants in Budapest is lower than it used to be in the early- and mid-90s, Chinese traders’ enduring presence can be expected in the city – especially in the rust belts of the 8th and 10th districts of Budapest, which became reviving areas thanks to migrants’ investments and business activities. The aim of my thesis is to explore what may reason the fact that despite the spatial concentration of Chinese trading enterprises these areas have not turned to form the basis of a “Chinatown”. However, according to my presumption, the formal recognition of a “Chinatown” would be beneficial both for the city and Chinese migrants. It may promote transnational migrants’ urban incorporation and could advance the city’s position as branding itself with the multicultural environment that these places constitute. For seeking answers to this question I have scrutinized not only the structural opportunities of the city and migrants’ transnational networks which surely condition these processes, but also made qualitative research on the city leadership’s and migrants’ opinion about the idea. Hence I both applied a top-down and a bottom-up approach for investigations. I paid special attention to determine that within the local context who may be affected by the institutionalization of a “Chinatown” negatively in terms of social inclusion. -

May 2007, Vol. 5, Issue 1

Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study Volume 5, Issue # 1 May 2007 One of our favorite group pictures, taken during the 2005 GENACIS workshop in Riverside, California. Many Old (and New) Friends Coming to Budapest The GENACIS workshop in Budapest will be one of the best-attended workshops in recent years. Thanks to travel funds in the new GENACIS grant, and additional support from the KBS organizing committee, a number of members from WHO- and PAHO-funded countries will be able to participate. They include Julio Bejarano (Costa Rica), Vivek Benegal (India), Akan Ibanga (Nigeria/UK), Florence Kerr-Correa (Brazil), Raquel Magri (Uruguay), Myriam Munné (Argentina), Martha Romero (Mexico), and Nazarius Tumwesigye (Uganda). (We apologize if we have forgotten someone!) Several new members will also join us. Among them are Jennie Connor (New Zealand), Danielle Edouard (France), Maria Lima (Brazil) , and guest Nancy Poole (Canada). We are all looking forward to meeting many old and new friends soon in Budapest. Newsletter Page 1 of 10 Some Highlights of 2007 GENACIS Workshop The GENACIS workshop in Budapest will include several new features. One is a series of overview presentations that will summarize major findings to date in the various GENACIS components. The overviews will be presented by Kim Bloomfield (EU countries), Isidore Obot (WHO-funded countries), Maristela Monteiro (PAHO-funded countries), and Sharon Wilsnack (other countries). Robin Room will provide a synthesis of findings from the various components. On Saturday afternoon, Moira Plant will facilitate a discussion of “GENACIS history and process.” GENACIS has faced a number of challenges and Members of the GENACIS Steering Committee at generated many creative solutions in its 15-year their December 2006 meeting in Berlin. -

Budapest Guide Online.Indd

Üdvözlünk Budapesten! We’re pleased to welcome you in Budapest for the 5th European Transgender Council. The Council will take place at the Rubin Wellness & Conference Hotel, 1- 4 May 2014. Our Budapest Travel Guide will help you plan your stay. We wish you a wonder- ful time in Budapest and would like to give you all the information to have a safe and pleasant time as our guests at the Pearl of Danube. We are looking forward to seeing you soon! Transvanilla Transgender Association team Coming to Hungary Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Panno- nian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The country’s capital and its largest city is Budapest. Hungary is a member of the European Union and the Schengen Area. There are no border controls between the countries that have signed and imple- mented the Schengen Agreement, which is comprised from 26 countries -- most of the European Union (except from Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Roma- nia and the United Kingdom), Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Likewise, a visa granted for any Schengen member country is valid in all other countries that have signed and implemented the treaty. To ensure that your journey is smooth we encourage you to bring the following documents when travelling: 1 • Valid Passport (if required) or ID • Visa (if required) • Photocopies of travel documents (return tickets, accommodation information, travel/medical insurance, etc.) There are restrictions about what you can bring into Hungary. -

Hungary: the Assault on the Historical Memory of The

HUNGARY: THE ASSAULT ON THE HISTORICAL MEMORY OF THE HOLOCAUST Randolph L. Braham Memoria est thesaurus omnium rerum et custos (Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things) Cicero THE LAUNCHING OF THE CAMPAIGN The Communist Era As in many other countries in Nazi-dominated Europe, in Hungary, the assault on the historical integrity of the Holocaust began before the war had come to an end. While many thousands of Hungarian Jews still were lingering in concentration camps, those Jews liberated by the Red Army, including those of Budapest, soon were warned not to seek any advantages as a consequence of their suffering. This time the campaign was launched from the left. The Communists and their allies, who also had been persecuted by the Nazis, were engaged in a political struggle for the acquisition of state power. To acquire the support of those Christian masses who remained intoxicated with anti-Semitism, and with many of those in possession of stolen and/or “legally” allocated Jewish-owned property, leftist leaders were among the first to 1 use the method of “generalization” in their attack on the facticity and specificity of the Holocaust. Claiming that the events that had befallen the Jews were part and parcel of the catastrophe that had engulfed most Europeans during the Second World War, they called upon the survivors to give up any particularist claims and participate instead in the building of a new “egalitarian” society. As early as late March 1945, József Darvas, the noted populist writer and leader of the National Peasant -

Budapest, the Banks of the Danube and the Buda Castle Quarter

WHC Nomination Documentation File name: 400.pdf UNESCO Region EUROPE SITE NAME ("TITLE") Budapest, the Banks of the Danube and the Buda Castle Quarter DATE OF INSCRIPTION ("SUBJECT") 11/12/1987 STATE PARTY ("AUTHOR") HUNGARY CRITERIA ("KEY WORDS") C (ii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: 11th Session The Committee took note of the statement made by the observer from Hungary that his Government undertook to make no modifications to the panorama of Budapest by adding constructions out of scale. BRIEF DESCRIPTION: This site, with the remains of monuments such as the Roman city of Aquincum and the Gothic castle of Buda, which have exercised considerable architectural influence over various periods, is one of the world's outstanding urban landscapes and illustrates the great periods in the history of the Hungarian capital. 1.b. State, province or region: Budapest 1.d Exact location: La zone concernée est situées au centre de la capitale, sur les deux rives du fleuve Danube. Sur la rive droite, à Buda, elle comprend le mont du Chateau avec le quartier annexe situé sur la rive et la masse du mont Géllert surplombant la fleuve. Application by the Hungarian Republic for the expansion of Budapests World Heritage Site Editor: Bálint Nagy and Partners Éva Tétényi Terézváros Program Office of Urban Development Zsófia Burányi, Erzsébet Buzál, László Jeager, András Tasnády Advisor: János Jelen, Ferenc Németh, Nóra Némethy, Dr. Lia Bassa, Ferenc Bor Szilvia Ódor, Róbert Kuszinger, Ilona Tahi Tóth, Piroska Czétényi Photographies: István Halas, Péter Tímár, József Hajdú, Zoltán Fábry, Teampannon Translation: Charles Horton, Csaba Czuczka Design: István Halas Published by: György Farkas Terézváros Municipality of Budapest Capital Supporter: Prof. -

Budapestflow.Com

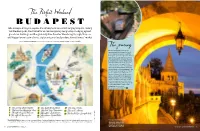

The Perfect Weekend BUDAPEST Take a couple of days to explore the atmospheric streets of Hungary’s capital, finding tumbledown pubs, thermal baths and contemporary design shops nudging against grand civic buildings and the gloriously blue Danube. Wandering through, fill up on old Magyar favourites in a Soviet-style canteen or local produce from a farmers’ market WORDS AMANDA CANNING @amandacanning l PHOTOGRAPHS SARAH COGHILL @SarahCoghill1 TheThe doors of Margit are pulledjourney shut, its passengers huddled within, and the tiered, wooden funicular is hoisted up Castle Hill, clanking beneath two wrought-iron pedestrian bridges on its 95-metre journey. Opened in 1870, the Budavári Sikló funicular still exerts a particular pull on visitors to Budapest: you can’t come and not ride at least once in its burgundy carriages. Emerging at the top, people soon disperse – some stopping to take photos with the armed sentries guarding the presidential palace, others rummaging for lace in an antiques shop or stopping for a Borsodi beer on a cobbled square. All will end up at Fisherman’s Bastion, a fanciful, Neo-Gothic terrace, complete with turrets, and dragons hiding in the stonework. It’s worth jostling past the inevitable crowds to peer through the bastion’s open windows at the Danube and Parliament far below, before diving back into the quieter streets of Castle Hill and making your own discoveries. l Return journey on funicular £4 Fisherman’s Bastion, built in the TRAVEL ESSENTIALS BA, easyJet, Jet2.com, Norwegian Air Shuttle, Ryanair and Wizz Air fly to Budapest from the UK (from £70; wizzair.com). -

The Jewish Quarter of Budapest

The Jewish Quarter of Budapest: Authenticity and Commodification of Culture ———— Fruzsina Csala Supervisor: Tatiana Debroux Advisor: Ruba Saleh Date of submission: 1st June 2020 Master thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies (VUB) and Master of Science in Geography, general orientation, track ‘Urban Studies’ (ULB) Master in Urban Studies – Academic year 2019-2020 Abstract Since the 1989 regime change, Inner-Erzsébetváros has undergone rapid transformation and gentrification. This process was not planned but the dialectics of top-down policies and bottom- up initiatives have been the force that shaped the neighbourhood for the past three decades. As being both the Jewish Quarter and the Party Quarter of Budapest, Inner-Erzsébetváros is the most controversial area of the historic city centre of Budapest. The Jewish Quarter is a symbolic space, as most of the representative places of the religious institutional system are located there, and also a space where Jewish culture is present in a commodified way both for Jews & non-Jews and tourists & locals alike. The Party Quarter as an accumulation of bars, nightclubs and eateries is a recent phenomenon of the 2010s. Such function of the neighbourhood is a result of unregulated service hours and a growing number of party tourists. In this context, the main research question – How does the Jewish heritage contribute to the present-day character of Inner-Erzsébetváros – provides a framework to the thesis. Two complementary sets of methods were used to answer the research question(s): (1) online desk research & stakeholder and expert interviews, and (2) perceptions mapping & in-depth field observation. -

Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal • 2020 Winter

HUNGARIAN ARCHAEOLOGY E-JOURNAL • 2020 WINTER www.hungarianarchaeology.hu A STRATIGRAPHIC SEQUENCE OF SIX THOUSAND YEARS Preliminary report on the rescue excavation at the site of the former Óbuda Distillery (BUSZESZ) Gábor SzilaS1 – Tibor budai baloGh2 – barbara hajdu3 – VikTória kiSjuháSz4 – adrienn Papp5 – nóra Szabó6 Hungarian Archaeology Vol. 9 (2020), Issue 4, pp. 1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.36338/ha.2020.4.6 Árpád period pit houses with a stone oven, Roman period brick graves and a public bath, debris from Middle Bronze Age buildings, an Early Bronze Age cemetery, and Late Copper Age clay pit complexes – the thousands of archaeological features that appeared one below the other in a several metres thick stratigraphic sequence, and the nearly thousand boxes of finds are only one side of the coin. The other is represented by the constant roar of the machines, the deafening noise and the dust clouds from the pneu- matic drill, the rhythmical sound of the suburban railway, the hubbub of construction workers, and the tight archaeological deadlines. At the site of the former Óbuda Distillery, during the almost three years of test and rescue excavations, we have encountered nearly all known elements of urban archaeology. We also appreciate that, in spite of the difficulties, we were given a unique, extraordinary and perhaps unparal- leled opportunity. The site, after all, lies at the edge of the historical cores of the Roman Military Town and medieval Óbuda. The excavation site is noteworthy not only in terms of its vertical but also its horizontal extent. Following the highly informative period of fieldwork, hopefully we can begin the analysis as soon as possible, through which we may understand, step by step, the significance of this special place, where, until now, there lay the stratigraphic sequence of six thousand years of human presence. -

THE PANTRIES of BUDAPEST TOURING the MARKET HALLS Ji Manu Delago Ensemble Akram Khan Company Ton Koopman

AT BUDAPEST’S BSF40 AMENHOTEP II’S MASTERFUL GATE: COLOUR YOUR BURIAL KNIVES RÁCKEVE SPRING CHAMBER FREE PUBLICATION FREE THE SPRING | 2020 FIVE STAR CITY GUIDE THE PANTRIES OF BUDAPEST TOURING THE MARKET HALLS Ji Manu Delago Ensemble Akram Khan Company Ton Koopman Tank and the Bangas Staatskapelle Weimar Kristine Opolais www.bsf.hu 1 SPRING | 2020 CONTENTS Budapest’s pantries 4 6 Colourful menu 6 Budapest's At Budapest’s Gate: pantries Ráckeve 14 Boat market on the shore 16 Cultural Quarter 20 The dream of the founders 22 NoGravity – Emiliano Pellisari 24 Nóra Bujdosó – set and costume designer 26 Music from the archives 28 Viennese evening 14 with Gábor Farkas 30 At Budapest's Ernő Kállai in the Vigadó 32 Russian pictures in French frames gate: – Marcell Szabó’s solo evening 34 anno 1935 Ráckeve Piazzolla in the market hall 36 Amenhotep II and his age 38 Pre-Raphaelites in the National Gallery 40 THE BEST DOBOS CAKE City Guide 42 Szamos Gourmet House 24 Jewellery box in the park 44 NoGravity Spring sporting events 46 The Szankovits Knives House 50 Dance Budapest100 Company – a weekend of open gates 52 Twentysix 54 Sándor Lakatos and slow fashion 56 Fashion queen behind the iron curtain 58 Stand25 relocated 60 58 Recommended reading 63 Fashion queen Programme corner 64 On the cover: behind the Cover photo: The Great Market Hall (Photo: © István Práczky ) iron curtain To see the location on the map, simply scan the QR code with your smartphone. SzamosGourmetHaz | www.szamos.hu | Tel.: +36 30 570 5973 2 Budapest, 5th district, Váci street 1. -

Assessment of Rehabilitation Possibilities in Case of Budapest Jewish Quarter Building Stock Viktória Sugár, Attila Talamon, András Horkai, Michihiro Kita

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Architectural and Environmental Engineering Vol:11, No:3, 2017 Assessment of Rehabilitation Possibilities in Case of Budapest Jewish Quarter Building Stock Viktória Sugár, Attila Talamon, András Horkai, Michihiro Kita network, the frequent T-shaped intersections, as well as the Abstract—The dense urban fabric of the Budapest 7th district is diverse width of the streets can be originated from the known as the former Jewish Quarter. The majority of the historical agricultural past of the area. This kind of organic fabric can building stock contains multi-story tenement houses with courtyards, th rarely be found in todays’ regulated Budapest [2]. built around the end of the 19 century. Various rehabilitation and urban planning attempt occurred until today, mostly left unfinished. Present paper collects the past rehabilitation plans, actions and their effect which took place in the former Jewish District of Budapest. The authors aim to assess the boundaries of a complex building stock rehabilitation, by taking into account the monument protection guidelines. As a main focus of the research, structural as well as energetic rehabilitation possibilities are analyzed in case of each building by using Geographic Information System (GIS) methods. Keywords—Geographic information system, Hungary, Jewish quarter, monument, protection, rehabilitation. I. INTRODUCTION HERE had been multiple “Jewish Quarters” in Budapest Tduring the previous centuries. On the Buda side of the River Danube, Jewish residents occupied a part of the Buda Castle Hill, and they also lived a little northern, in Óbuda. On the Pest side, the so-called Old Pest Jewish Quarter is situated in the neighborhood of the present District 7; the new Jewish Quarter of Budapest later became Újlipótváros, todays’ District 13 [1]. -

Museum Quarter As an Urban Formative Core the Urban Planning Aspects of Its Development and 1 Berlin

VÝSKUM NAVRHOVANIA MUSEUM QUARTER AS AN URBAN FORMative CORE MUSEUM QUARTER AS AN URBAN FORMative CORE THE URBAN PLANNING ASPECTS OF ITS DEVelopMENT AND 1 Berlin. Museum Island. Map with the Palace of the Republic, 2006. Electronic resource: http://mapsof. net/berlin/karte-berlin-museumsinsel. Request from POSITION IN THE CITY GRID culture, some kind of “museum models” of around the whole world and, especially, in the 01.02.2016 perception and interpretation of the world. USA and Western Europe. Presenting a huge The very postmodernism culture becomes scale of cultural area and combining usually (A CASE STUDY OF BERLIN, 4 a museum.” the most popular and valuable city museums, This new type of cultural thinking results MQ affects different branches of social, cul- VIENNA AND BUDAPEST in creation of some kind of virtual–spatial tural and urban development. The overview museum or an artistic medium, which usual- of pre-requirements of MQ shows that such ly doesn’t fit in a box of traditional museum a process is not an accident. The necessity of spatial MODELS) buildings and requires new principles of or- creation of Museum Quarter is a logical result ganization and functionality of museum ins- of several parallel tendencies: Ekaterina Kochergina titution. Exactly such principles lead to appe- – An outcome of long-term museum arance of Museum Quarters as new types of development, “In a contemporary This statement was announced in 1984 as a long time considered as elitist and conserva- socio-cultural environment. Here should be – The result