The Meaning of Meteora As an Orthodox Monastic Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DONALD NICOL Donald Macgillivray Nicol 1923–2003

DONALD NICOL Donald MacGillivray Nicol 1923–2003 DONALD MACGILLIVRAY NICOL was born in Portsmouth on 4 February 1923, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister. He was always proud of his MacGillivray antecedents (on his mother’s side) and of his family’s connection with Culloden, the site of the Jacobite defeat in 1745, on whose correct pronunciation he would always insist. Despite attending school first in Sheffield and then in London, he retained a slight Scottish accent throughout his life. By the time he left St Paul’s School, already an able classical scholar, it was 1941; the rest of his education would have to wait until after the war. Donald’s letters, which he carefully preserved and ordered with the instinct of an archivist, provide details of the war years.1 In 1942, at the age of nineteen, he was teaching elementary maths, Latin and French to the junior forms at St-Anne’s-on-Sea, Lancashire. He commented to his father that he would be dismissed were it known that he was a conscientious objector. By November of that year he had entered a Friends’ Ambulance 1 The bulk of his letters are to his father (1942–6) and to his future wife (1949–50). Also preserved are the letters of his supervisor, Sir Steven Runciman, over a forty-year period. Other papers are his diaries, for a short period of time in 1944, his notebooks with drawings and plans of churches he studied in Epiros, and his account of his travels on Mount Athos. This material is now in the King’s College London Archives, by courtesy of the Nicol family. -

Preserving & Promoting Understanding of the Monastic

We invite you to help the MOUNT ATHOS Preserving & Promoting FOUNDATION OF AMERICA Understanding of the in its efforts. Monastic Communities You can share in this effort in two ways: of Mount Athos 1. DONATE As a 501(c)(3), MAFA enables American taxpayers to make tax-deductible gifts and bequests that will help build an endowment to support the Holy Mountain. 2. PARTICIPATE Become part of our larger community of patrons, donors, and volunteers. Become a Patron, OUr Mission Donor, or Volunteer! www.mountathosfoundation.org MAFA aims to advance an understanding of, and provide benefit to, the monastic community DONATIONS BY MAIL OR ONLINE of Mount Athos, located in northeastern Please make checks payable to: Greece, in a variety of ways: Mount Athos Foundation of America • and RESTORATION PRESERVATION Mount Athos Foundation of America of historic monuments and artifacts ATTN: Roger McHaney, Treasurer • FOSTERING knowledge and study of the 2810 Kelly Drive monastic communities Manhattan, KS 66502 • SUPPORTING the operations of the 20 www.mountathosfoundation.org/giving monasteries and their dependencies in times Questions contact us at of need [email protected] To carry out this mission, MAFA works cooperatively with the Athonite Community as well as with organizations and foundations in the United States and abroad. To succeed in our mission, we depend on our patrons, donors, and volunteers. Thank You for Your Support The Holy Mountain For more than 1,000 years, Mount Athos has existed as the principal pan-Orthodox, multinational center of monasticism. Athos is unique within contemporary Europe as a self- governing region claiming the world’s oldest continuously existing democracy and entirely devoted to monastic life. -

Post-ADE FAM Tour Classical Tour of History, Culture and Gastronomy April 18 - 22, 2018

Post-ADE FAM Tour Classical Tour of History, Culture and Gastronomy April 18 - 22, 2018 WHERE: Athens – Argolis – Olympia – Meteora –Athens WHEN: April 18-22, 2018 ITINERARY AT A GLANCE: • Wednesday, April 18 o Athens - Corinth Canal - Argolis - Nafplio • Thursday, April 19 o Nafplio – Arcadia - Olympia • Friday, April 20 o Nafpaktos – Delphi - Arachova • Saturday, April 21 o Hosios Lukas – Meteora • Sunday, April 22 o Meteora Monasteries – Thermopylae - Athens COST: Occupancy Price* Double Occupancy $735 Single Occupancy $953 Reservations on this tour MUST be made by December 31, 2017. WHAT’S INCLUDED*: • Private Land Travel o 5-day excursion o Private vehicle o English speaking driver o Gas and toll costs o Fridge with water, refreshments and snacks • Private Guided tours o Mycenae (1.5hr) - State licensed guide o Epidaurus (1.5hr) - State licensed guide o Nafplio Orientation tour (1.5 hr) - State licensed guide o Olympia (2hrs) - State licensed guide o Augmented reality Ipads o Delphi (2hrs) - State licensed guide o Meteora (3.5hrs) – Sunset tour – Specialized local guide o Meteora (5 hrs) – Monasteries tour - State licensed guide Classical Tour of History, Culture and Gastronomy I April 18 - 22, 2018 I Page 1 of 6 WHAT’S INCLUDED (cont.)*: • Entry Fees o Mycenae o Epidaurus o Olympia o Delphi o Hosios Lukas o Meteora Monasteries • Activities o Winery Visit & Wine Tasting in Nemea o Winery Visit & Wine Tasting in Olympia o Olive oil and olives tasting in Delphi • Meals o Breakfast and lunch or dinner throughout the 5-day itinerary • Taxes o All legal taxes • Accommodations– Double room occupancy o Day 1– Nafplio 4* hotel o Day 2 – Olympia 4* hotel o Day 3 – Arachova 5* hotel o Day 4 – Meteora 4* Hotel ESSENTIAL INFORMATION: • A minimum of 2 persons is required to operate this tour. -

Grand Tour of Greece, 7 Days

GRAND TOUR OF GREECE Escorted Motor-Coach Tour Departure dates: April 22, May 13 & 27, June 24 & 26, July 15, August 5, September 9, 16 & 23 7 days / 6 nights: 1 night in Olympia, 1 night in Delphi, 1 night in Kalambaka, 3 nights in Thessaloniki Accommodation Meals Tours Transportation Transfer Also includes Olympia Breakfast daily Tours as per itinerary. Modern Airport transfers Professional tour Hotel Arty Grand or similar air-conditioned included if arrival and director (English Delphi For the Monasteries, motorcoach or departure is on the language only) Hotel Amalia or similar ladies are requested minibus. scheduled days. Kalambaka Hotel Amalia or similar to wear a skirt and Service charge & hotel Thessaloniki gentlemen long taxes Mediterranian Palace or similar trousers. Land Rates 2021 US$ per Person Day by Day Itinerary Dates Twin Single Day 1: 8:45am - departure from Athens. Drive on and visit the Theatre of Epidaurus. Then All dates $1,572 $1,998 proceed to the Town of Nafplio, drive on to Mycenae and visit their major sights. Then depart for Olympia the cradle of the ancient Olympic Games. Overnight here. ← Thessaloniki Day 2: In the morning visit the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus, the Ancient Stadium, the spot where the torch of the modern Olympic Games is lit and the Archaeological Museum. Then drive on through the plains of Ilia and Achaia. Pass by the picturesque towns of Nafpactos (Lepanto) and Itea, arrive in Delphi. ← Day 3: In the morning visit the Museum of Delphi, the most famous oracle of the ancient Kalabaka ← world. Depart for Kalambaka, a small town located at the foot of the astonishing complex of Meteora. -

Epidemic Waves of the Black Death in the Byzantine Empire

Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 3, 193-201, 2011 Le infezioni Epidemic waves of the Black nella sto - Death in the Byzantine Empire ria della medicina (1347-1453 AD) Ondate epidemiche della Morte Nera nell’Impero Bizantino Infections (1347-1453 d.C.) in the history of medicine Costas Tsiamis 1, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou 2, Athanassios Tsakris 3, Eleni Petridou 1 1Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Athens Medical School, University of Athens, Greece; 2Department of History of Medicine, Athens Medical School, University of Athens, Greece; 3Department of Microbiology, Athens Medical School, University of Athens, Greece n INTRODUCTION a small geographical area is impressive; it is ba - sically a case of “all against all”. The Republics he completeness of the Byzantine historiog - of Venice and Genova held strategic and eco - raphy of the plague epidemics in the 14 th and nomically important areas in the region after T15 th century cannot be compared with that the 4 th Crusade (1204) and were in permanent of the West. References made to the plague are conflict with the Byzantines for control of the often in conjunction with other concurrent his - Aegean Sea and the trade roads [2, 3]. torical events. The political turmoil and the de - In the east, the Ottoman Turks of Asia Minor cline experienced by the Empire in the 13 th and exert pressure on the Empire of Trebizond, in - 14 th century gradually changed the mentality of vading the Balkan Peninsula, detaching Greek Byzantine scholars. Military defeats, civil wars, territories of the Byzantine Empire, while fight - earthquakes and natural disasters were joined by ing with Venice, Genova and the Knights of the plague, which exacerbated the people’s sense Saint John of Rhodes for control of the sea [4, 5]. -

Contested Authenticity Anthropological Perspectives of Pilgrimage Tourism on Mount Athos

religions Article Contested Authenticity Anthropological Perspectives of Pilgrimage Tourism on Mount Athos Michelangelo Paganopoulos Global Inquiries and Social Theory Research Group, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; [email protected] Abstract: This paper investigates the evolution of customer service in the pilgrimage tourist industry, focusing on Mount Athos. In doing so, it empirically deconstructs the dialectics of the synthesis of “authentic experience” between “pilgrims” and “tourists” via a set of internal and external reciprocal exchanges that take place between monks and visitors in two rival neighboring monasteries. The paper shows how the traditional value of hospitality is being reinvented and reappropriated according to the personalized needs of the market of faith. In this context, the paper shows how traditional monastic roles, such as those of the guest-master and the sacristan, have been reinvented, along with traditional practices such as that of confession, within the wider turn to relational subjectivity and interest in spirituality. Following this, the material illustrates how counter claims to “authenticity” emerge as an arena of reinvention and contestation out of the competition between rival groups of monks and their followers, arguing that pilgrimage on Athos requires from visitors their full commitment and active involvement in their role as “pilgrims”. The claim to “authenticity” is a matter of identity and the means through which a visitor is transformed from a passive “tourist” to Citation: Paganopoulos, an active “pilgrim”. Michelangelo. 2021. Contested Authenticity Anthropological Keywords: authenticity; spirituality; Mount Athos; hospitality; pilgrimage tourism Perspectives of Pilgrimage Tourism on Mount Athos. -

Athens, Corinth, Meteora, Philippi, Thessalonica & Delphi

First Class 8 Day Winter Package Athens, Corinth, Meteora, Philippi, Thessalonica & Delphi Day 1: Departure from US nearby Acropolis where our guide will speak on the worship prac - Today we embark on our Journey to the lands of ancient treasures tices and point out the bird’s eye view of what was a bustling city and Christian history with an overnight flight to Athens. Prepare of around 800,000 during Paul’s stay. Before ending our day we yourself for a life-changing experience. Get some rest on the visit Cenchreae, the ancient port region of Corinth. Acts 18:18, flight…Tomorrow you will be walking where the apostles walked! states the Apostle Paul stopped at Cenchreae during his second missionary journey, where he had his hair cut to fulfill a vow. We Day 2: Arrive Athens return to Athens for the evening. We arrive in Athens and check into our hotel. You will have the re - mainder of the day free to relax or take a stroll along the streets of Day 4: Athens, Acropolis & Mars Hill Athens to enjoy the flavor of the city. This evening our group will We visit the Acropolis, the Parthenon, and Erectheum before enjoy the first of many delectable European style dinners. viewing Athens atop Mars Hill where Paul stood and preached the truth to the Gentile nation. Additional sites include the Agora (an - Day 3: Ancient Corinth cient market place and center of Athenian public life), the House Departing Athens, we stop for a rest stop and photos at the of Parliament, Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Olympic Stadium, Corinth Canal and then travel to the ancient city of Corinth, an - and Presidential Palace. -

Greek Tourism 2009 the National Herald, September 26, 2009

The National Herald a b September 26, 2009 www.thenationalherald.com 2 GREEK TOURISM 2009 THE NATIONAL HERALD, SEPTEMBER 26, 2009 RELIGIOUS TOURISM Discover The Other Face of Greece God. In the early 11th century the spring, a little way beyond, were Agios Nikolaos of Philanthropenoi. first anachorites living in the caves considered to be his sacred fount It is situated on the island of Lake in Meteora wanted to find a place (hagiasma). Pamvotis in Ioannina. It was found- to pray, to communicate with God Thessalonica: The city was ed at the end of the 13th c by the and devote to him. In the 14th cen- founded by Cassander in 315 B.C. Philanthropenoi, a noble Constan- tury, Athanassios the Meteorite and named after his wife, Thessa- tinople family. The church's fres- founded the Great Meteora. Since lonike, sister of Alexander the coes dated to the 16th c. are excel- then, and for more than 600 years, Great. Paul the Apostle reached the lent samples of post-Byzantine hundreds of monks and thousands city in autumn of 49 A.D. painting. Visitors should not miss in of believers have travelled to this Splendid Early Christian and the northern outer narthex the fa- holy site in order to pray. Byzantine Temples of very impor- mous fresco depicting the great The monks faced enormous tant historical value, such as the Greek philosophers and symboliz- problems due to the 400 meter Acheiropoietos (5th century A.D.) ing the union between the ancient height of the Holy Rocks. They built and the Church of the Holy Wisdom Greek spirit and Christianity. -

Highlights of Ancient Greece Trip Notes

Current as of: September 26, 2019 - 15:22 Valid for departures: From January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020 Highlights of Ancient Greece Trip Notes Ways to Travel: Guided Group 9 Days Land only Trip Code: Destinations: Greece Min age: 16 AGM Leisurely Programmes: Culture Trip Overview Starting in the capital city Athens, we’ll visit some of the most signicant archaeological sites in the country, including the Acropolis, Ancient Mycenae and Epidaurus. We’ll also visit the mediaeval castle town of Mystras, Ancient Olympia, where the rst Olympic Games took place, Delphi, where heaven and earth met in the ancient world, and the unique 'stone forest' of Meteora, one of the largest Orthodox communities in Greece and the Balkans. At the same time we’ll cover a large part of mainland Greece, including the Peloponnese Peninsula and Central Greece, enjoying both the beautiful coastline and lush forests and mountains! At a Glance 8 nights 3-star hotels with en suite facilities Travel by minibus Trip Highlights Explore the ancient sites of Mystras and Delphi Visit Olympia, the site of the rst Olympic Games Enjoy spectacular Meteora- 'columns in the sky' Is This Trip for You? This is a cultural trip of Greece’s major archaeological sites, combining coastal areas in the Peloponnese Peninsula with several mountainous areas and villages in Greece. Beautiful landscapes, incredible history and culture are the highlights of this tour. A fair amount of travelling (by minibus) is involved, ranging from 2 to 4 hours per day, well balanced though between sightseeing en route, visiting key sites, lunch breaks and some free time, usually upon arrival at each day’s destination. -

Mount Athos(Greece)

World Heritage 30 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, 10 April / 10 avril 2006 Original: English / anglais Distribution limited / distribution limitée UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Thirtieth session / Trentième session Vilnius, Lithuania / Vilnius, Lituanie 08-16 July 2006 / 08-16 juillet 2006 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. JOINT UNESCO/WHC-ICOMOS-IUCN EXPERT MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION CONJOINTE DES EXPERTS DE L’UNESCO/CPM, DE L’ICOMOS ET DE L’IUCN Mount Athos (Greece) (454) / Mont Athos (Grece) (454) 30 January – 3 February 2006/ 30 janvier – 3 février 2006 This mission report should be read in conjunction with Document: Ce rapport de mission doit être lu conjointement avec le document suivant: WHC-06/30.COM/7A WHC-06/30.COM/7A.Add WHC-06/30.COM/7B WHC-06/30.COM/7B.Add REPORT ON THE JOINT MISSION UNESCO – ICOMOS- IUCN TO MOUNT ATHOS, GREECE, FROM 30 JANUARY TO 3 FEBRUARY 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS 1 BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION o Inscription history o Inscription criteria -

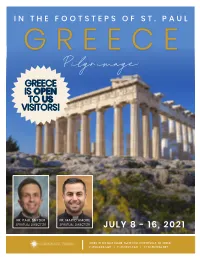

Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN to US VISITORS!

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ST. PAUL GREECE Pilgrimage GREECE IS OPEN TO US VISITORS! FR. PAUL SNYDER FR. MARIO AMORE SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR SPIRITUAL DIRECTOR JULY 8 - 16, 2021 41780 W SIX MILE ROAD, SUITE 1OO, NORTHVILLE, MI 48168 P: 866.468.1420 | F: 313.565.3621 | CTSCENTRAL.NET READY TO SEE THE WORLD? PRICING STARTING AT $1,699 PER PERSON, DOUBLE OCCUPANCY PRICE REFLECTS A $100 PER PERSON EARLY BOOKING SAVINGS FOR DEPOSITS RECEIVED BEFORE JUNE 11, 2021 & A $110 PER PERSON DISCOUNT FOR TOURS PAID ENTIRELY BY E-CHECK LEARN MORE & BOOK ONLINE: WWW.CTSCENTRAL.NET/GREECE-20220708 | TRIP ID 45177 | GROUP ID 246 QUESTIONS? VISIT CTSCENTRAL.NET TO BROWSE OUR FAQ’S OR CALL 866.468.1420 TO SPEAK TO A RESERVATIONS SPECIALIST. DAY 1: THURSDAY, JULY 8: OVERNIGHT FLIGHT FROM USA TO ATHENS, GREECE Depart the USA on an overnight flight. St. Paul the Apostle, the prolific writer of the New Testament letters, was one of the first Christian missionaries. Trace his journey through the ancient cities and pastoral countryside of Greece. DAY 2: FRIDAY, JULY 9: ARRIVE THESSALONIKI Arrive in Athens on your independent flights by 12:30pm.. Transfer on the provided bus from Athens to the hotel in Thessaloniki and meet your professional tour director. Celebrate Mass and enjoy a Welcome Dinner. Overnight Thessaloniki. DAY 3: SATURDAY, JULY 10: THESSALONIKI Tour Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, sitting on the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea. Founded in 315 B.C.E. by King Kassandros, the city grew to be an important hub for trade in the ancient world. -

ICONIC GREECE 2021 2 a Celebration of Eye, Mind and Spirit About Your Tour Leaders

Nick Melidonis [email protected] 0418912156 (from within Australia) +61418912156 (outside Australia) “Everything here speaks now as it did centuries ago, of illumination. Here the light penetrates directly to the soul, opens the door and windows of the heart, makes one naked, exposed, isolated in a metaphysical bliss which makes everything so clear without being known” ~Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussa After two decades of conducting tours to Greece and the Greek Islands; Nick and Eva offer more jewels of Greece to savour in an exciting new adventure. We will have our own personal coach and driver for the entire tour. This remarkable journey is about experiencing Greek culture, history, food, art, dance, shopping and connecting with the local people; plus, the opportunity to take stunning images with ‘insider’s knowledge’. It’s also about making friends and creating memories. Our journey commences in classical Athens from where we travel to ancient Delphi, with its evocative ruins surrounded by breathtaking mountain scenery; surely one the most beautiful historic sites in Greece. From Delphi; we travel north through the mighty chasms of the Eastern Pindus as they plummet abruptly onto the Thessalian plain. Here we will marvel at the massive grey coloured pinnacles with the imposing monasteries of Meteora perched on top. These monasteries make spectacular photographs, especially at dawn and dusk. We journey along a stunning coastline via the historic battle site of Thermopylae where the Spartan King Leonidas made his famous stand in 480 BC. Our journey continues to an area of stunning beauty and rich culture in the Peloponnese to the treasures of Byzantium as we commence with a visit to the old capital of Greece; the beautifully preserved city of Nafplion.