Pillbugs, Sowbugs, Centipedes, Millipedes, and Earwigs1 P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Chiricahua July 16–28, 2019

CAMP CHIRICAHUA JULY 16–28, 2019 An adult Spotted Owl watched us as we admired it and its family in the Chiricahuas © Brian Gibbons LEADERS: BRIAN GIBBONS, WILLY HUTCHESON, & ZENA CASTEEL LIST COMPILED BY: BRIAN GIBBONS VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM By Brian Gibbons Gathering in the Sonoran Desert under the baking sun didn’t deter the campers from finding a few life birds in the parking lot at the Tucson Airport. Vermilion Flycatcher, Verdin, and a stunning male Broad-billed Hummingbird were some of the first birds tallied on Camp Chiricahua 2019 Session 2. This was more than thirty years after Willy and I had similar experiences at Camp Chiricahua as teenagers—our enthusiasm for birds and the natural world still vigorous and growing all these years later, as I hope yours will. The summer monsoon, which brings revitalizing rains to the deserts, mountains, and canyons of southeast Arizona, was tardy this year, but we would see it come to life later in our trip. Rufous-winged Sparrow at Arizona Sonora Desert Museum © Brian Gibbons On our first evening we were lucky that a shower passed and cooled down the city from a baking 104 to a tolerable 90 degrees for our outing to Sweetwater Wetlands, a reclaimed wastewater treatment area where birds abound. We found twittering Tropical Kingbirds and a few Abert’s Towhees in the bushes surrounding the ponds. Mexican Duck, Common Gallinule, and American Coot were some of the birds that we could find on the duckweed-choked ponds. -

Occasional Invaders

This publication is no longer circulated. It is preserved here for archival purposes. Current information is at https://extension.umd.edu/hgic HG 8 2000 Occasional Invaders Centipedes Centipede Millipede doors and screens, and by removal of decaying vegetation, House Centipede leaf litter, and mulch from around the foundations of homes. Vacuum up those that enter the home and dispose of the bag outdoors. If they become intolerable and chemical treatment becomes necessary, residual insecticides may be Centipedes are elongate, flattened animals with one pair of used sparingly. Poisons baits may be used outdoors with legs per body segment. The number of legs may vary from caution, particularly if there are children or pets in the home. 10 to over 100, depending on the species. They also have A residual insecticide spray applied across a door threshold long jointed antennae. The house centipede is about an inch may prevent the millipedes from entering the house. long, gray, with very long legs. It lives outdoors as well as indoors, and may be found in bathrooms, damp basements, Sowbugs and Pillbugs closets, etc. it feeds on insects and spiders. If you see a centipede indoors, and can’t live with it, escort it outdoors. Sowbugs and pillbugs are the only crustaceans that have Centipedes are beneficial by helping controlArchived insect pests and adapted to a life on land. They are oval in shape, convex spiders. above, and flat beneath. They are gray in color, and 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch long. Sowbugs have two small tail-like Millipedes appendages at the rear, and pillbugs do not. -

House Centipedes: Lots of Legs, but Not a Hundred House Centipedes Are Predatory Arthropods That Can Be Found Both Indoors and Outdoors

http://hdl.handle.net/1813/43838 2015 Community House Centipedes: Lots of Legs, but not a Hundred House centipedes are predatory arthropods that can be found both indoors and outdoors. They prefer damp places, including basements, bathrooms and even pots of over-watered plants, where they feed on insects and spiders. As predators of other arthropods, they can be considered a beneficial organism, but are most often considered a nuisance pest when present in the home. Did you know … ? • By the Numbers: There are approximately 8,000 species of Common House Centipede (Scutigera coleoptrata Linnaeus). Photo: G. Alpert. centipedes. • Form-ally Speaking: Centipedes come in a variety of forms and sizes. Depending on the species they can be red, brown, black, white, orange, or yellow. Some species are shorter than an inch, while tropical species can be up to a foot in length! • Preying on the Predators: Larger centipedes can feed on mice, toads, and even birds. • Preference or Requirement? Centipedes prefer moist areas because they lack a waxy exoskeleton. In dry areas, centipedes can die from desiccation or drying out. Identification Common House Centipede close-up. Photo: G. Alpert. Adult house centipedes measure one to two inches in length, but may appear larger because of their 15 pair of long legs. House centipedes are yellow-gray in color, with three black stripes that span the length of the body, and black bands on their legs. The last pair of legs is very long and is modified to hold onto prey items. These and other legs can be detached defensively if grasped by a predator. -

Millipedes and Centipedes

MILLIPEDES AND CENTIPEDES Integrated Pest Management In and Around the Home sprouting seeds, seedlings, or straw- berries and other ripening fruits in contact with the ground. Sometimes individual millipedes wander from their moist living places into homes, but they usually die quickly because of the dry conditions and lack of food. Occasionally, large (size varies) (size varies) numbers of millipedes migrate, often uphill, as their food supply dwindles or their living places become either Figure 1. Millipede (left); Centipede (right). too wet or too dry. They may fall into swimming pools and drown. Millipedes and centipedes (Fig. 1) are pedes curl up. The three species When disturbed they do not bite, but often seen in and around gardens and found in California are the common some species exude a defensive liquid may be found wandering into homes. millipede, the bulb millipede, and the that can irritate skin or burn the eyes. Unlike insects, which have three greenhouse millipede. clearly defined body sections and Life Cycle three pairs of legs, they have numer- Millipedes may be confused with Adult millipedes overwinter in the ous body segments and numerous wireworms because of their similar soil. Eggs are laid in clutches beneath legs. Like insects, they belong to the shapes. Wireworms, however, are the soil surface. The young grow largest group in the animal kingdom, click beetle larvae, have only three gradually in size, adding segments the arthropods, which have jointed pairs of legs, and stay underneath the and legs as they mature. They mature bodies and legs and no backbone. soil surface. -

Millipedes and Centipedes? Millipedes and Centipedes Are Both Arthropods in the Subphylum Myriapoda Meaning Many Legs

A Teacher’s Resource Guide to Millipedes & Centipedes Compiled by Eric Gordon What are millipedes and centipedes? Millipedes and centipedes are both arthropods in the subphylum Myriapoda meaning many legs. Although related to insects or “bugs”, they are not actually insects, which generally have six legs. How can you tell the difference between millipedes and centipedes? Millipedes have two legs per body segment and are typically have a body shaped like a cylinder or rod. Centipedes have one leg per body segment and their bodies are often flat. Do millipedes really have a thousand legs? No. Millipedes do not have a thousand legs nor do all centipedes have a hundred legs despite their names. Most millipedes have from 40-400 legs with the maximum number of legs reaching 750. No centipede has exactly 100 legs (50 pairs) since centipedes always have an odd number of pairs of legs. Most centipedes have from 30- 50 legs with one order of centipedes (Geophilomorpha) always having much more legs reaching up to 350 legs. Why do millipedes and centipedes have so many legs? Millipedes and centipedes are metameric animals, meaning that their body is divided into segments most of which are completely identical. Metamerization is an important phenomenon in evolution and even humans have a remnant of former metamerization in the repeating spinal discs of our backbone. Insects are thought to have evolved from metameric animals after specializing body segments for specific functions such as the head for sensation and the thorax for locomotion. Millipedes and centipedes may be evolutionary relatives to the ancestor of insects and crustaceans. -

House Centipede

Colorado Arthropod of Interest House Centipede Scientific Name: Scutigera coleoptrata (L.) Class: Chilopoda (Centipedes) Order: Scutigeromorpha (House centipedes) Figure 1. House centipede. Family: Scutigeridae (House centipedes) Description and Distinctive Features: The house centipede (Figure 1) has 15 pairs of extraordinarily long legs, the last pair often exceeding the body length (Figure 2). The overall body is usually grayish-yellow and marked with three stripes running longitudinally. Banding also occurs on the legs. A pair of very long antennae protrude from the head (Figure 3). The eyes, although not prominent, are larger than found with most other centipedes. Full- grown the body length typically ranges from 1- 1 ½ inches; with the legs and antennae extended it may be 3-4 inches. Distribution in Colorado: Native to the Mediterranean, the house centipede has spread over Figure 2. House centipede, side-view. Some much of the world, largely with the aid of human legs are missing on the left side of the body. transport. Potentially it can occur in any home in the state. Life History and Habits: Typical of all centipedes, the house centipede is a predator of insects and other small invertebrates, immobilizing them with a pair of specialized fang-like front legs (maxillipeds). They are normally active at night but may hunt during the day in dark indoor rooms. The house centipede is the only centipede that can adapt to indoor life, provided it has some access to moisture. Populations may also develop outdoors; with the advent of cool weather many of these may be forced indoors, causing an increase in sighting during late summer and early fall. -

Some Aspects of the Ecology of Millipedes (Diplopoda) Thesis

Some Aspects of the Ecology of Millipedes (Diplopoda) Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Monica A. Farfan, B.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Hans Klompen, Advisor John W. Wenzel Andrew Michel Copyright by Monica A. Farfan 2010 Abstract The focus of this thesis is the ecology of invasive millipedes (Diplopoda) in the family Julidae. This particular group of millipedes are thought to be introduced into North America from Europe and are now widely found in many urban, anthropogenic habitats in the U.S. Why are these animals such effective colonizers and why do they seem to be mostly present in anthropogenic habitats? In a review of the literature addressing the role of millipedes in nutrient cycling, the interactions of millipedes and communities of fungi and bacteria are discussed. The presence of millipedes stimulates fungal growth while fungal hyphae and bacteria positively effect feeding intensity and nutrient assimilation efficiency in millipedes. Millipedes may also utilize enzymes from these organisms. In a continuation of the study of the ecology of the family Julidae, a comparative study was completed on mites associated with millipedes in the family Julidae in eastern North America and the United Kingdom. The goals of this study were: 1. To establish what mites are present on these millipedes in North America 2. To see if this fauna is the same as in Europe 3. To examine host association patterns looking specifically for host or habitat specificity. -

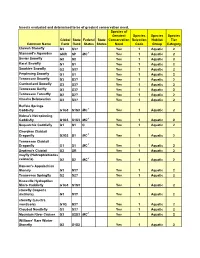

Insects Evaluated and Determined to Be of Greatest Conservation Need

Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. Species of Greatest Species Species Species Global State Federal State Conservation Selection Habitat Tier Common Name Rank Rank Status Status Need Code Group Category Etowah Stonefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Stannard's Agarodes GNR SP MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sevier Snowfly G2 S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Karst Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Smokies Snowfly G2 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Perplexing Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cumberland Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Sallfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Forestfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cheaha Beloneurian G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Buffalo Springs Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Helma's Net-spinning Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sequatchie Caddisfly G1 S1 C Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cherokee Clubtail Dragonfly G2G3 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Clubtail Dragonfly G1 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Septima's Clubtail G2 SR Yes 1 Aquatic 2 mayfly (Habrophlebiodes celeteria) G2 S2 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Hanson's Appalachian Stonely G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Springfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Knoxville Hydroptilan Micro Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Isoperla distincta) G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Leuctra monticola) G1Q S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Clouded Needlefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Mountain River Cruiser G3 S2S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Williams' Rare Winter Stonefly G2 S1S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Con't...Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. -

Scolopendra Gigantea (Giant Centipede)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Scolopendra gigantea (Giant Centipede) Order: Scolopendromorpha (Tropical Centipedes) Class: Chilpoda (Centipedes) Phylum: Arthropoda (Arthropods) Fig. 1. Giant centipede, Scolopendra gigantea. [http://eol.org/data_objects/31474810, downloaded 2 February 2017] TRAITS. Scolopendra gigantea is the world’s largest species of tropical centipede, with a documented length of up to about 30cm (Shelley and Kiser, 2000). They have flattened and unequally segmented bodies, separated into a head and trunk with lateral legs; covered in a non- waxy exoskeleton (Fig. 1). Coloration: the head ranges from dark brown to reddish-brown and the legs are olive-green with yellow claws (Khanna and Yadow, 1998). Each segment of the trunk has one pair of legs, of an odd number; 21 or 23 pairs (Animal Diversity, 2014). There are two modified pairs of legs, one pair at the terminal segment are long and antennae-like (anal antennae), for sensory function, and the other pair are the forcipules, located behind the head, modified for venom delivery from a poison gland in predation and defence (UTIA, 2017). S. gigantea displays little sexual dimorphism in the segment shape and gonopores (genital pores), however, the females may have more segments (Encyclopedia of Life, 2011). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. Found in the north parts of Colombia and Venezuela, and the islands of Margarita, Trinidad, Curacao, and Aruba (Fig. 2) (Shelley and Kiser, 2000). HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. Scolopendra gigantea is a neotropical arthropod with a non- waxy, impermeable exoskeleton (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1958). -

Biology Management Options House Centipede

Page: 1 (revision date:7/14/2015) House centipede Use Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for successful pest management. Biology The house centipede (<i>Scutigera coleoptrata</i>) is a slender, flattened, many-segmented arthropod approximately 1 to 1 1/2 inches long. It can be found throughout the United States, both in and outdoors in warmer areas, and primarily indoors in colder regions. This centipede is grayish-yellow in color with three dark stripes running along its back. Adults have fifteen pairs of long, fragile legs. The long, delicate antennae and the last pair of legs are both longer than the body. Newly hatched nymphs have four pairs of legs, with additional pairs being added with each molt. House centipedes are quick, agile hunters of spiders and insects, including flies, cockroaches, moths, and many other insects found indoors. They are usually active at night and run very quickly, holding their body up on its long legs. House centipedes prefer damp areas; frequently they are found in basements, bathrooms, closets, or potted plants. As with all centipedes, house centipedes have strong mouthparts with large jaws. They may inflict a painful bite if handled. While they can be considered beneficial since they are predators and aid in control of indoor insect pests, house centipedes usually alarm homeowners and can be a nuisance in the home. Management Options Non-Chemical Management ~ House centipedes prefer moist areas. To aid in control, reduce moisture in areas such as basements, bathrooms, etc. Provide adequate ventilation in crawl spaces. ~ Remove debris from houseplant pots and trays to reduce centipede hiding places. -

Sexual Behaviour and Morphological Variation in the Millipede Megaphyllum Bosniense (Verhoeff, 1897)

Contributions to Zoology, 87 (3) 133-148 (2018) Sexual behaviour and morphological variation in the millipede Megaphyllum bosniense (Verhoeff, 1897) Vukica Vujić1, 2, Bojan Ilić1, Zvezdana Jovanović1, Sofija Pavković-Lučić1, Sara Selaković1, Vladimir Tomić1, Luka Lučić1 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Studentski Trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: copulation duration, Diplopoda, mating success, morphological traits, sexual behaviour, traditional and geometric morphometrics Abstract Analyses of morphological traits in M. bosniense ..........137 Discussion .............................................................................138 Sexual selection can be a major driving force that favours Morphological variation of antennae and legs morphological evolution at the intraspecific level. According between sexes with different mating status ......................143 to the sexual selection theory, morphological variation may Morphological variation of the head between sexes accompany non-random mating or fertilization. Here both with different mating status .............................................144 variation of linear measurements and variation in the shape Morphological variation of gonopods (promeres of certain structures can significantly influence mate choice in and opisthomeres) between males with different different organisms. In the present work, we quantified sexual mating status ....................................................................144 behaviour of the -

Fossil Calibrations for the Arthropod Tree of Life

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/044859; this version posted June 10, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. FOSSIL CALIBRATIONS FOR THE ARTHROPOD TREE OF LIFE AUTHORS Joanna M. Wolfe1*, Allison C. Daley2,3, David A. Legg3, Gregory D. Edgecombe4 1 Department of Earth, Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 3 Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PZ, UK 4 Department of Earth Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fossil age data and molecular sequences are increasingly combined to establish a timescale for the Tree of Life. Arthropods, as the most species-rich and morphologically disparate animal phylum, have received substantial attention, particularly with regard to questions such as the timing of habitat shifts (e.g. terrestrialisation), genome evolution (e.g. gene family duplication and functional evolution), origins of novel characters and behaviours (e.g. wings and flight, venom, silk), biogeography, rate of diversification (e.g. Cambrian explosion, insect coevolution with angiosperms, evolution of crab body plans), and the evolution of arthropod microbiomes. We present herein a series of rigorously vetted calibration fossils for arthropod evolutionary history, taking into account recently published guidelines for best practice in fossil calibration.