Liberation Theology: Problematizing the Historical Projects of Democracy and Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grassroots Catholic Groups and Politics in Brazil

GRASSROOTS CATHOLIC GROUPS AND POLITICS IN BRAZIL, 1964-1985 Scott Mainwaring Working Paper #98 - August 1987 Scott Mainwaring is Assistant Professor of Government and member of the Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame. He has written extensively on the Catholic Church and politics, social movements, and transitions to democracy. The author wishes to thank Caroline Domingo, Frances Hagopian, Margaret Keck, Alfred Stepan, and Alexander Wilde for helpful suggestions. ABSTRACT During most of its lengthy history, the Catholic Church in Latin America has been identified with dominant elites and the state. This situation has changed in recent decades as Church leaders have supported popular protest aimed at changing unjust social structures. At the forefront of the process of ecclesiastical change have been a panoply of new grassroots groups, the most famous of which are the ecclesial base communities (CEBs). This paper examines the relationship between such grassroots groups and politics in Brazil. The author calls attention to the strong linkages between these groups and the hierarchy. He also underscores the central religious character of CEBs and other groups, even while arguing that these groups did have a political impact. The paper traces how the political activities of CEBs and other grassroots groups evolved over time, largely in response to macropolitical changes. It pays particular attention to the difficulties poor Catholics often encountered in acting in the political sphere. RESUMEN Durante la mayor parte de su larga historia, la Iglesia Católica en Latinoamérica se ha identificado con las élites dominantes. Esta situación ha cambiado en las décadas recientes ya que líderes de la Iglesia han apoyado la protesta popular dirigida al cambio de estructuras sociales injustas. -

And Unemployment in South Africa Today

Page 1 of 8 Original Research Modern slavery in the post-1994 South Africa? A critical ethical analysis of the National Development Plan promises for unemployment in South Africa Author: In African ethics, work is not work if it is not related to God or gods. Work, or umsebenzi, is 1 Vuyani S. Vellem for God or gods ultimately; work without God is the definition of slavery in my interpretation Affiliation: of the African ethical value system. If one succeeds from that understanding to define what 1Department of Dogmatics slavery is, then God-lessness in work might imply the need for us to search for the gods of and Christian Ethics, modernity post-1994 that have dethroned God, if they have not disentangled work from God. University of Pretoria, This article looks at the problem of unemployment by analysing the National Development South Africa Plan (NDP) and in particular the solutions proposed in relation to unemployment in South Correspondence to: Africa. The article examines the language and grammar of the NDP to evaluate its response to Vuyani Vellem the violent history of cheap, docile and migratory labour in South Africa. Email: [email protected] Moderne slawerny in die post-1994 Suid-Afrika? ‘n Kritiese en etiese analise van die Postal address: nasionale Ontwikkelingsplan se beloftes aangaande werkloosheid in Suid-Afrika. Private Bag X20, Hatfield 0028, South Africa In Afrika-etiek word die idee van ‘werk’ aan God of gode gekoppel. Werk, of umsebenzi, is uiteindelik vir God of gode; volgens my interpretasie van die Afrika-etiese waardestelsel Dates: is werk sonder God gelykstaande aan slawerny. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Joerg Rieger Distinguished Professor of Theology Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair in Wesleyan Studies Founding Director of the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice Divinity School and Graduate Department of Religion Vanderbilt University ACADEMIC POSITIONS Vanderbilt University, Divinity School and Graduate Program in Religion Distinguished Professor of Theology and Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair in Wesleyan Studies, 2016-. Founding Director of the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice, 2019-. Affiliate Faculty Turner Family Center for Social Ventures, Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University. Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University Wendland-Cook Endowed Professor of Constructive Theology, 2009-2016. Professor of Systematic Theology, 2004-2008. Associate Professor of Systematic Theology, 2000-2004. Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology, 1994-2000. Visiting Professor/Scholar Theologisches Studienjahr, Dormitio Abbey, Jerusalem, Israel, November 2018. United Theological College (UTC), Bangalore, India, October 2018. Seminary Consortium for Urban Pastoral Education (SCUPE), Chicago, June 2016. Claremont School of Theology, Claremont, CA, Spring 2015. Universidade Metodista Sao Paulo, Brazil, Semana Wesleyana, May 2014. Hamline University, St. Paul, Minnesota, Mahle Lecturer in Residence, April 2013. National Labor College, Silver Springs, Maryland, Fall 2013, semester-long seminar on labor and social movements. University of Kwazulu Natal, School of Religion and Theology, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, Spring 2008. Lecturer Duke University Divinity School, Durham, NC, 1992-1994. Theologisches Seminar in Reutlingen, Germany, Lecturer in Greek, 1988-1989. EDUCATION Duke University, Durham, NC: Ph.D., Theology and Ethics, 1994. Duke University Divinity School, Durham, NC: Th.M., Theology and Ethics, 1990. Theologische Hochschule Reutlingen, Reutlingen, Germany: M.Div., 1989. -

Climate Change and Southern Theologies. a Latin American Insight ∗∗∗ As Alterações Climáticas E As Teologias Do Sul

Dossiê: Biodiversidade, Política, Religião – Artigo original DOI Licença Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Climate change and Southern theologies. A Latin American insight ∗∗∗ As alterações climáticas e as teologias do sul. Uma visão da América Latina. ∗∗ Guillermo Kerber Resumo A luta pela justiça e libertação encontra-se no centro dos movimentos e das reflexões teológicas latino-americanas há décadas. De que modo os movimentos sociais, os líderes políticos, os teólogos e os cristãos tratam atualmente os desafios da mudança climática? Como eles os relacionam com o contexto global? O presente artigo, baseado numa apresentação feita pelo autor para uma audiência nórdica européia, apresenta a gênesis e a matriz das teologias latino-americanas e alguns de seus principais expoentes, como Leonardo Boff, Juan Luis Segundo e Gustavo Gutierrez. Destaca também os novos empreendimentos que permitem uma abordagem dos assuntos relacionados às mudanças climáticas, chamados de teologias indígenas, eco-teologias, teologia e economia e teologia eco- feminista, construídos a partir das publicações de teólogos como Boff e Ivone Gebara. Em seguida, o autor destaca alguns dos principais componentes dessa relação, enfocando o imperativo ético de justiça climática, a renovada teologia da criação e a dimensão espiritual da abordagem. Palavras-chave : Teologia latino-americana; Ecologia; Alterações climáticas; Ética; Justiça. Abstract The struggle for justice and liberation has been at the core of theological movements and reflections in Latin America for decades. How do social movements, political leaders, theologians and Christians address the challenges of climate change nowadays? How do they relate them to the global context? This article, based on a presentation made by the author to a European Nordic audience, focuses on the genesis and matrix of Latin American theologies and some of their key authors, such as Leonardo Boff, Juan Luis Segundo and Gustavo Gutierrez. -

The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: a Practical Theology Approach

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2016 The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: A Practical Theology Approach Hannah Kristine Adams Ingram University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Practical Theology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Hannah Kristine Adams, "The Myth of the Saving Power of Education: A Practical Theology Approach" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1229. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1229 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE MYTH OF THE SAVING POWER OF EDUCATION: A PRACTICAL THEOLOGY APPROACH __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Hannah Adams Ingram November 2016 Advisor: Katherine Turpin ©Copyright by Hannah Adams Ingram 2016 All Rights Reserved Author: Hannah Adams Ingram Title: THE MYTH OF THE SAVING POWER OF EDUCATION: A PRACTICAL THEOLOGY APPROACH Advisor: Katherine Turpin Degree Date: November 2016 Abstract U.S. political discourse about education posits a salvific function for success in formal schooling, specifically the ability to “save” marginalized groups from poverty by lifting them into middle- class success. -

“The Fall of the Second Wall”: the Normalization of Relations Between Cuba and the United States and the Role of Pope Francis

Pablo A. Baisotti1 Oригинални научни рад Sun Yat Sen University UDC: 327(729.1:73) China 272-732.2:929 Francis, Pope “THE FALL OF THE SECOND WALL”: THE NORMALIZATION OF RELATIONS BETWEEN CUBA AND THE UNITED STATES AND THE ROLE OF POPE FRANCIS Abstract The pastoral trips of Pope Francis to Cuba and to the United States were not only religious. The political activity that he organized to consolidate the relation- ship between the two recently reconciled countries was remarkable. Through visits, meetings and masses the Pope expressed his position and concerns about various arguments, beyond the recomposed Cuban-American relationship. Dur- ing the trip he addressed subjects including the environment, poverty, family, union, freedom, all of which were themes that the Pontiff had clearly stated in his encyclical Laudato Si ‘(2015) and his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (2013). With this trip, Pope Francis ended up consolidating his status as a global politician as well as a pastor with a high degree of acceptance not only among Catholics. Keywords: Pope Francisco, Cuba, United States, Obama, Castro, Apostolic Journey Introduction The centrality and notoriety that Pope Francis2 has obtained over the last few years is undeniable. It can even be said that few pontiffs have played as much of a global political role as Francis. This, of course, has raised voices from both defenders and detractors. The former have affirmed that a renewal was neces- sary, and praise the Pope’s approach to addressing the “common” people with simple language and an energetic way of acting, defying the rigid vatican struc- tures. -

SSRN-Id1373826.Pdf (328.4Kb)

Sanctioning Faith: Religion, Politics, and U.S.-Cuban Relations The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Goldenziel, Jill I. "Sanctioning Faith: Religion, State, and US-Cuban Relations." Journal of Law and Politics 25 (2009): 179-210. Published Version https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jlp25&i=183 Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364804 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, WARNING: This file should NOT have been available for downloading from Harvard University’s DASH repository.;This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of-use#OAP 1 Sanctioning Faith: Religion, State, and U.S.-Cuban Relations Jill I. Goldenziel1 Forthcoming, 25 J. LAW AND POLITICS 2 (2009) Abstract Fidel Castro’s government actively suppressed religious life in Cuba for decades. Yet in recent years Cuba has experienced a dramatic flourishing of religious life. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cuban government has increased religious liberty by opening political space for religious belief and practice. In 1991, the Cuban Communist Party removed atheism as a prerequisite for party membership. One year later, Cuba amended its constitution to deem itself a secular state rather than an atheist state. Since that time, religious life in Cuba has grown exponentially. All religious denominations, from the Catholic Church to Afro-Cuban religious societies and the Jewish and Muslim communities, report increased participation in religious rites. -

Radicalizing Reformation – Provoked by the Bible and Today's Crises 94 Theses

Radicalizing Reformation – Provoked by the Bible and Today's Crises 94 Theses “You shall proclaim liberation throughout the land” (Lev. 25:10). Martin Luther began his 95 Theses of 1517 with Jesus’ call for repentance as a change of mind and direction: “Return, the just world of God has come near!” Five hundred years later is also a time that brings to mind the biblical “Jubilee Year” (Lev 25), calling for repentance and conversion toward a more just society. For us today, this is not in opposition to the Catholic Church and the many liberation movements rooted there, but in opposition to the realities of empire that rule. As we hear the testimony of the cross (1 Cor 1:18) and the groaning of the abused creation ( Rom 8:22) and as we actively hear the cries of those victimized by our world (dis-)order driven by hyper-capitalism – only then can we turn this Reformation commemoration into a liberating jubilee. Christian self-righteousness, supporting the dominating system, is in contradiction to faith-righteousness as proclaimed by the Reformation. This must be lived out through just, all-inclusive solidarity. We are theologians – predominantly Lutheran but also Reformed, Methodist, Anglican, and Mennonite – from different parts of the world, who are involved in an ongoing project of reconsidering the biblical roots and contemporary challenges facing Reformation theology today. The rampant destruction of human and non-human life in a world ruled by the totalitarian dictatorship of money and greed, market and exploitation requires a radical re-orientation towards the biblical message, which also marked the beginning of the Reformation. -

Interpretations of Church and State in Cuba, 1959–1961

INTERPRETATIONS OF CHURCH AND STATE IN CUBA, 1959–1961 BY JOHN C. SUPER* Unrestrained excitement greeted Fidel Castro when he entered Ha- vana on January 8, 1959. More than any other leader of the revolution- ary forces,he personified Cuba’s potential to become a progressive and democratic republic. Castro’s immense popularity helped to overcome for a brief period the divisions over political philosophies and programs that soon fractured Cuban life. The Catholic Church stood at the center of the controversies that un- folded, for both what it did and did not do. Until recently, the Church was one of the least studied aspects of the Cuban revolution, almost as if it were a voiceless part of Cuban society,an institution and faith that had little impact on the course of events. Beginning in the 1980’s more extensive and serious analyses of the revolution began to appear, and for the most part these studies lacked the emotional charges and coun- tercharges so common in revolutionary historiographies. Instead of at- tempting systematically to survey all of the literature, this essay selects works that represent the main interpretations of church-state relations. Among the many works available, those of Juan Clark and John M. Kirk deserve notice at the outset.1 Though their works differ in tone, focus, *Dr.Super is a professor of history in West Virginia University.He wishes to thank Juan M. Clark and Antonio de la Cova for their many helpful suggestions on this essay. 1Juan Clark,Cuba:Mito y Realidad.Testimonios de un Pueblo (Miami,1990),which in- cludes much of his Religious Repression in Cuba (Coral Gables: 1985); John M. -

The Unmarried (M)Other: a Study of Christianity, Capitalism, and Counternarratives Concerning Motherhood and Marriage in the United States and South Africa

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Religious Studies Theses and Dissertations Religious Studies Winter 12-21-2019 The Unmarried (M)Other: A Study of Christianity, Capitalism, and Counternarratives Concerning Motherhood and Marriage in the United States and South Africa Haley Feuerbacher Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/religious_studies_etds Part of the Africana Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feuerbacher, Haley, "The Unmarried (M)Other: A Study of Christianity, Capitalism, and Counternarratives Concerning Motherhood and Marriage in the United States and South Africa" (2019). Religious Studies Theses and Dissertations. 19. https://scholar.smu.edu/religious_studies_etds/19 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE UNMARRIED (M)OTHER: A STUDY OF CHRISTIANITY, CAPITALISM, AND COUNTERNARRATIVES CONCERNING MOTHERHOOD AND MARRIAGE IN THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA Approved by: ____________________________________ Dr. Joerg Rieger Distinguished Professor of Theology, Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies, and Founding Director of the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice at Vanderbilt Divinity School Dr. Crista Deluzio Associate Professor and Altshuler Distinguished Teaching Professor of History and US Women, Children, and Families Dr. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Joerg Rieger Wendland-Cook Endowed

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Joerg Rieger Wendland-Cook Endowed Professor of Constructive Theology Perkins School of Theology Southern Methodist University ACADEMIC POSITIONS Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University Wendland-Cook Endowed Professor of Constructive Theology, since 2009. Professor of Systematic Theology, 2004-2008. Associate Professor of Systematic Theology, 2000-2004. Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology, 1994-2000. Visiting Professorships University of Kwazulu Natal, School of Religion and Theology, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, Spring 2008. Hamline University, St. Paul, Minnesota, Mahle Lecturer in Residence, April 2013. National Labor College, Silver Springs, Maryland, Fall 2013, semester-long seminar on labor and social movements. Universidade Metodista Sao Paulo, Brazil, Lecturer for Semana Wesleyana, May 2014. Duke University Lecturer, 1992-1994. Theologisches Seminar in Reutlingen, Germany Lecturer in Greek, 1988-1989. EDUCATION Duke University, Durham, NC: Ph.D., Theology and Ethics, 1994. Duke Divinity School, Durham, NC: Th.M., Theology and Ethics, 1990. Theologisches Seminar der Evangelisch-methodistischen Kirche, Reutlingen, Germany: M.Div., 1989. Universität Tübingen, Germany, Greek and Hebrew (Graecum, Hebraicum), 1987-1989. Heinrich-von-Zügel Gymnasium, Murrhardt, Germany: Abitur, 1983. Majors in German, Religion, Music, and Physics. ORDINATION Ordained Elder, North Texas Conference, United Methodist Church, June 1997. Ordained Deacon, North Texas Conference, United Methodist Church, June 1995. Affiliate member of the Süddeutsche Jährliche Konferenz of the United Methodist Church in Germany, 1984-1995. Curriculum Vitae: Joerg Rieger, p. 2 PUBLICATIONS Books, Authored: Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude. Theology in the Modern World Series. Co- authored with Kwok Pui-lan. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2012. Traveling: Christian Explorations of Daily Living. -

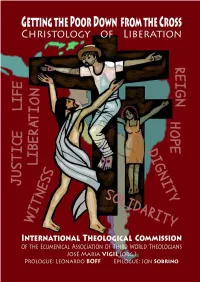

Getting the Poor Down from the Cross: a Christology of Liberation

GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation International Theological Commission of the ECUMENICAL ASSOCIATION OF THIRD WORLD THEOLOGIANS EATWOT GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation José María VIGIL (organizer) International Teological Commission of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians EATWOT / ASETT Second Digital Edition (Version 2.0) First English Digital Edition (version 1.0): May 15, 2007 Second Spanish Digital Edition (version 2.0): May 1, 2007 Frist Spanish Digital Edition (version 1.0): April 15, 2007 ISBN - 978-9962-00-232-1 José María VIGIL (organizer), International Theological Commission of the EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians, (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo). Prologue: Leonardo BOFF Epilogue: Jon SOBRINO Cover & poster: Maximino CEREZO BARREDO © This digital book is the property of the International Theological Commission of the Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT/ ASETT) who place it at the disposition of the public without charge and give permission, even recommend, its sharing, printing and distribution without profit. This book can be printed, by «digital printing», as a professionally formatted and bound book. Software can be downloaded from: http://www.eatwot.org/TheologicalCommission or http://www.servicioskoinonia.org/LibrosDigitales A 45 x 65 cm poster, with the design of the cover of the book can also be downloaded there. Also in Spanish, Portuguese, German and Italian. A service of The International Theological Commission EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo) CONTENTS Prologue, Getting the Poor Down From the Cross, Leonardo BOFF .