University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moisture-Excluding Effectiveness of Finishes on Wood Surfaces

United States Department of Agriculture The Moisture- Forest Service Forest Excluding Products Laboratory Research Paper Effectiveness FPL 462 of Finishes on Wood Surfaces William C. Feist James K. Little Jill M. Wennesheimer Abstract Permeability to water vapor is one of the more important properties affecting the performance of coatings and other wood finishes. Often, one of the main purposes of finishing wood is to restrict moisture movement from the surroundings. We evaluated the moisture-excluding effectiveness (MEE) of 91 finishes on ponderosa pine sapwood, using the Forest Products Laboratory method in which finished and unfinished wood specimens in equilibrium with 30 percent relative humidity (RH) at 80 °F are weighed before and after exposure to 90 percent RH at 80 °F. Finishes with the best MEE were pigmented, nonaqueous (solvent-borne) finishes. Two-component epoxy paint systems had MEE values greater than 85 percent after 14 days when three coats were put on the wood. Molten paraffin wax and a sheathing grade, two-component epoxy material with no solvent were the very best finishes found in this study for controlling moisture vapor movement into wood. The MEE is a direct function of the number of coats of finish applied to the wood (film thickness) and the length of time of exposure to a particular humidity. Only 11 finishes were found to retard moisture vapor movement into wood with any degree of success over the relatively short time of 14 days, and then only when two or three coats were applied. These studies include evaluations of MEE by finish type, number of coats, substrate type, sample size, and time of exposure, and describe the effect on MEE of repeated adsorption/desorption cycles. -

Understanding Wood Bonds–Going Beyond What Meets the Eye: a Critical Review

Understanding Wood Bonds–Going Beyond What Meets the Eye: A Critical Review Christopher G. Hunt1*, Charles R. Frihart1, Manfred Dunky2 and Anti Rohumaa3 1Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin, USA 2Kronospan GmbH Lampertswalde, Lampertswalde, Germany 3FibreLaboratory, South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Sciences (XAMK), Savonlinna, Finland Abstract: Understanding why wood bonds fail is an excellent route toward understanding how to make them better. Certifying a bonded product usually requires achieving a specifc load, percent wood failure, and an ability to withstand some form of moisture exposure without excessive delamination. While these tests protect the public from catastrophic failures, they are not very helpful in understanding why bonds fail. Understanding failure often requires going beyond what meets the naked eye, conducting additional tests, probing the wood surface, the fracture surface, adhesive properties, and the interaction of wood and adhesive during bond formation and service. This review of wood bond analysis methods reviews fundamentals of wood bonding and highlights recent developments in the analyses and understanding of wood bonds. It concludes with a series of challenges facing the wood bonding community. Keywords: Wood adhesive, wood bond, microscopy, penetration, failure List of Abbreviations AFM Atomic Force Microscopy AP Average Penetration CLSM Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy CV Collapsed Vessel CWBL Chemical Weak Boundary Layer DCB Dual Cantilever Beam DIC Digital Image Correlation DMA -

System Three Clear Finishing of Outdoor Wood

apply a second coat. See Product Application Guide for complete Sanding: Allow the unassembled wood parts to cure for instructions. several days before sanding. Wipe each piece with a damp The epoxy coating is as thick as ten coats of dry varnish or sponge prior to sanding. Begin sanding with 80 or 100 polyurethane, so only two or three coats of clear varnish or LPU grit paper. Finish with 150 or 220 paper. Wet sanding will usually be required to build a deep, rich fi nish. on thoroughly coated pieces is acceptable as the wood is now waterproof. Maintenance: If the fi nish becomes dull or begins to fl ake after PREMIUM ADHESIVES & COAT INGS several years of exposure it can easily be sanded to remove any Assembly: After sanding, put the parts together once loose or chalky material, and recoated. Reapplying varnish or more without glue to make sure that the joints still LPU before it weathers off will allow you to avoid reapplying the fi t. Sand to a fi t if necessary. Use System Three T- epoxy coating. 88® structural epoxy adhesive to glue the parts. It is waterproof and will not shrink on curing. Apply mixed With the System Three resin and varnish combination protecting adhesive to both bonding surfaces, with an excess on your clear-fi nished project from the elements, it will remain bright and beautiful for years to come. CLEAR the concave or female surface. Press the pieces together and wipe up any excess glue. Keep glued parts in place during cure. Avoid excess clamping pressure. -

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov. Architectural form and representation: Some principles American beginnings of modernism: The Chicago School Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” 1896 https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/architecture/4-205-analysis-of-contemporary- architecture-fall-2009/readings/MIT4_205F09_Sullivan.pdf 18 Nov. Organic architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture,” 1908 https://www.architecturalrecord.com/ext/resources/news/2016/01- Jan/InTheCause/Frank-Lloyd-Wright-In-the-Cause-of-Architecture-March- 1908.pdf “Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect,” Museum of Modern Art, 1940: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2992 Architectural Forum, special issue on Wright, January 1938: https://usmodernist.org/AF/AF-1938-01.pdf 25 Nov. European beginnings of modernism: Walter Gropius Gropius, “Bauhaus Manifesto and Programme,” 1919 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropBau19.p df Gropius, “Principles of Bauhaus Production,” 1926 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropPrdctn.p df Gropius, ”The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus,” 1923, in Herbert Bayer, Bauhaus 1919-1928, Museum of Modern Art: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2735_300190238.pdf De Stijl: Gerrit Rietveld Theo van Doesburg, First De Stijl Manifesto, 1918 https://www.readingdesign.org/de-stijl-manifesto Rietveld, “The New Functionalism in Dutch Architecture,“ 1932 https://modernistarchitecture.wordpress.com/2010/10/20/gerrit-rietveld- %E2%80%9Cnew-functionalism-in-dutch-architecture%E2%80%9D-1932/ Machines for Living: Le Corbusier Le Corbusier, “Five Points Towards a New Architecture,” 1926 https://www.spaceintime.eu/docs/corbusier_five_points_toward_new_archit ecture.pdf Le Corbusier, “Towards a New Architecture,” 1927 https://archive.org/details/TowardsANewArchitectureCorbusierLe/page/n91/ mode/2up E1027: Eileen Gray Joseph Rykwert, “Eileen Gray, Design Pioneer,” 1968. -

The Design of New Buildings in Historical Urban Context: Formal Interpretation As a Way of Transforming Architectural Elements of the Past

THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ELİF BEKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE SEPTEMBER 2018 Approval of the thesis: THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST submitted by ELİF BEKAR in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar _________________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Cânâ Bilsel _________________ Head of Department, Architecture Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Supervisor, Architecture Dept., METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc.Prof. Dr. Haluk Zelef _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Esin Boyacıoğlu _________________ Department of Architecture, Gazi University Date: 07.09.2018 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Elif Bekar Signature : ____________________ iv ABSTRACT THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST Bekar, Elif M.Arch., Department of Architecture Supervisor: Prof. -

Interpretation of Minimalism in Architecture According to Various Culture

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 10 Issue 07, July-2021 Interpretation of Minimalism in Architecture According to Various Culture Swetha Elangovan1 , Madhumathi.A2 1 Student, School of Architecture, VIT University, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India 2Professor, School of Architecture, VIT University, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India Abstract:- Minimalism is agreeable as a cultural definition that has an aesthetic approach towards various fields. Since the 1960s, minimalism has been a common movement of art, architecture and lifestyle. Minimalism is a name used to define arts that flourish in content and form with simplicity, as well as a sign of private expressiveness. Minimalism is recognized by reasoning as concept of culture. The modern culture is somehow impregnated by minimalism. Simplicity in architecture allows the user’s/ viewers to experience and grasp the work instantly. Necessary elements in architecture to achieve a simplicity design is limited no. of. materials, play with light, color, and geometric forms and most importantly removing the minor elements to highlight the major elements. The idea of this study is to comprehend how different cultures have diverse understandings towards minimalist architecture. Key words: Minimalist Architecture, Culture, Interpretation, Western, Japanese. 1. INTRODUCTION From 1960s, minimalism has been a common movement of art, architecture and lifestyle. Visual arts and architecture are differentiated and conveyed at one of the points is modernism as a category of art-object (Macarthur, 2002). It is reasonable to say that minimalism is a self-aware version of modernism where it reflects the current way of life. Minimalism concentrated on the most essential elements and a form’s simplicity and it is believed to be evolved from the modern movement whereas few philosophers tend to disagree by indicating that minimalism is indeed very closely linked to a user’s lifestyle and culture. -

PETER ZUMTHOR RECONSIDERS LACMA on VIEW: JUNE 9-SEPTEMBER 15, 2013 LOCATION: Resnick Pavilion

^ Pacific Standard Time PRESENTS: MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN L.A. EXHIBITION: THE PRESENCE OF THE PAST: PETER ZUMTHOR RECONSIDERS LACMA oN VIEW: JUNE 9-SEPTEMBER 15, 2013 LOCATION: resnick pavilion (Los Angeles-January 14, 2013) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA. This exhibition about the proposed future of LACMA’s campus is part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. initiative. The exhibition will be divided into three sections, with the first devoted to an exploration of the museum’s buildings within the complicated history of Hancock Park—a unique site with explicit ties to Los Angeles’s primordial past. For the first time in an exhibition, LACMA will analyze the development of its campus and explain how financial restrictions, political compromises, and unrealized plans have impacted the museum’s architectural aesthetic and art-viewing experience. This section will include rarely seen materials relating to unrealized master plans for LACMA by Renzo Piano and Rem Koolhaas, as well as new insights about the designs by William Pereira, Bruce Goff, and more. Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has been commissioned to rethink the east campus at LACMA by addressing challenges raised by the original structures, and to present a different approach, one that posits a new relationship to the historic site as well as examines the function of an encyclopedic museum in the twenty-first century. The exhibition will display Zumthor’s preliminary ideas about housing LACMA’s permanent collections, including several large models built by the architect’s studio. -

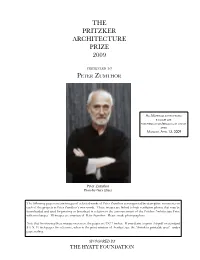

The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2009

THE PRITZKER ARCHITECTURE PRIZE 2009 PRESENTED TO PETER ZUMTHOR ALL MA TERI A LS IN THIS PHOTO BOOKLET A RE FOR PUBLICATION/BRO A DC A ST ON OR A FTER MOND A Y , APRIL 13, 2009 Peter Zumthor Photo by Gary Ebner The following pages contain images of selected works of Peter Zumthor accompanied by descriptive comments on each of the projects in Peter Zumthor’s own words. These images are linked to high resolution photos that may be downloaded and used for printing or broadcast in relation to the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize with no charges. All images are courtesy of Peter Zumthor. Please credit photographers. Note that for viewing these images on screen, the pages are 9X12 inches. If you desire to print this pdf on standard 8½ X 11 inch paper for reference, when in the print window of Acrobat, use the “shrink to printable area” under page scaling. SPONSORED BY THE HYatt FOUNDatION 2007 Brother Klaus Field Chapel Wachendorf, Eifel, Germany (this page and opposite) Photo by Walter Mair sketch by Peter Zumthor The field chapel dedicated to Swiss Saint Nicholas von der Flüe (1417–1487), known as Brother Klaus, was commissioned by farmer Hermann- Josef Scheidtweiler and his wife Trudel and largely constructed by them, with the help of friends, acquaintances and craftsmen on one of their fields above the village. The interior of the chapel room was formed out of 112 tree trunks, which were configured like a tent. In twenty- four working days, layer after layer of concrete, each layer 50 cm thick, was poured and rammed around the tent- like structure. -

The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990S

Redesigning the Physical Boundary: The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990s 潘 夢斐* Mengfei PAN 1.INTRODUCTION Contemporary museum architecture is buildings’ exalted status. This kind of seeing an age of glass. Both renovation extensive glazing has become an almost projects and new constructions have been indispensable part of the new generation of exploiting glass extensively, as if it is the museum architecture. best solution to serve the spatial functions, By contextualizing the phenomenon of present the architects’ concepts, and address extensive glazing in museum architecture, the institutions’ missions and social this paper aims to discern its connections expectations. Prominent examples include with the museum situation and the the Louvre Pyramid by I. M. Pei (1989) contemporaneity and locality of Japan. It and SANAA’s designs for The 21st Century argues that the increasing exploitation of Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa glass in museum architecture demonstrates (2004) and Louvre-Lens, France (2012). the influence of Neoliberalism on the public This trend of increasing use of glass by institutions and the architects to embrace museum architecture deviates from the visually appealing, technologically demanding, previous model of museums, temples and and commercial elements. It challenges the shrines, with grand staircases and formidable pre-dominant association of glass with look. A new physical boundary of museums, transparency and modernity and argues for a glass walls with their possibility to mediate contextualized reading of glass. Previous visual penetration and similarity with media research in the field of architectural studies interfaces that interact with the surrounding focused on glass employment in all types of and the spectators, is designed in contrast buildings and overlooked the specific with the older type that stresses the situation of museums; while museum studies * Ph. -

Western Timber Frame™ SCAPE

Made by: Western Timber Frame™ SCAPE TM ® The Ultimate Pergola & Pavilion Guide Everything you wanted to know about: Pergolas • Pavilions • Arbors • Trellises & More Coauthored by: Steven Bunker & Marilynn Thompson SCAPE TM ® Table of Contents Coauthored by: Steven Bunker and Marilynn Thompson Ultimate Pergola and Pavilion Guide Table of Contents ------------------------------ 6 What is a Pergola? ----------------------------- 8 What are Pavilions and Gazebos? ------------ 9 What is an Arbor or Trellis? ------------------ 10 Other Structures ----------------------------- 11 The Dovetail Difference™ -------------------- 12 Benefits of the Dovetail Difference™ --------- 14 Conventional Timber Framing --------------- 15 What makes us different -------------------- 16 Features and Benefits ----------------------- 17 Heavy Timber Kits ---------------------------- 18 Douglas Fir -------------------------------- 19 Douglas Fir Cont... Free Of Heart --------- 20 Vinyl --------------------------------------- 21 Aluminum ---------------------------------- 21 Customized Design --------------------------- 22 Choose your Style ---------------------------- 23 Tuscany Style -------------------------------- 26 Southwest Style ------------------------------ 26 ShadeScape™ series -------------------------- 27 Attached Kits - Extend your Home ---------- 38 Standard Options ----------------------------- 39 Color Selection ------------------------------- 49 Concept to Creation -------------------------- 76 Meet your Design Manager ------------------ 77 3D -

Investigating the Mechanisms of the Formation of Spiral Grain and Interlocked Grain in Wood

Investigating the mechanisms of the formation of spiral grain and interlocked grain in wood A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Plant Biotechnology in the University of Canterbury by Stephanie M. Dijkstra University of Canterbury 2020 Chapter 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisory team. To my original senior supervisor Dr David Collings – thank you for your crazy ideas that made this thesis possible. To Dr Ashley Garrill, thank you for your tireless support during this journey. To Dr Clemens Altaner, thank you for Secondly, I would like to acknowledge the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, both for the two scholarships that I received from them and for the whanaungatanga and mātauranga that being part of their scholars brought. I would like to acknowledge the technical staff from the school of biological sciences, the school of forestry and the school of geology for their support. Thank you for going along with the many left-field ideas that I often arrived with, and the generosity that each of you had with your time and knowledge. Thanks to the most amazing lab group (both past and present) that I could have asked for. Not only have you been fantastic co-workers, but I feel privileged to count you among my close friends (Cell bio Jedi for life!). Special thanks to Liz, Louise, Azy and Annabella for coffee, tea, chocolate and laughter when it was most needed Thanks to my family for always believing in me and providing support in all its forms. -

Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions, London, 2000-12

Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS lecture Art Pavilions in Public Parks SERPENTINE GALLERY ART PAVILIONS, LONDON, 2000-12 [email protected] Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) keyword: ART PAVILIONS IN PUBLIC PARKS 1811-17: Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (Sir John Soane) 1897-98: Secession Building, Vienna (Joseph Maria Olbrich) 1908-09: Jakopič Pavilion, Ljubljana (Maks Fabiani) 1895-1995: Bienalle National Pavilions, Venice 2000-12: Serpentine Gallery Pavilions, London 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013: Trimo Urban Crash Competition, Ljubljana Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) http://dulwichgalleryfriends.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/quiz-plan-soane.jpg https://museuminsider.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/dulwich-picture-gallery.jpg London, 1811-17: John Soane: first public art gallery; symmetrical ground floor plan; Dulwich Picture Gallery façade without windows; ground floor plan the sky lights illuminate the paintings indirectly; Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) Latham, I., (1980): Joseph Maria Olbrich. Academy Editions, London: str 25. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Secession_Vienna_June_2006_017.jpg Vienna, 1897-98: Joseph Maria Olbrich: public art gallery for Secession artists; symmetrical ground floor plan; Secession Building pure geometric forms; ground floor plan linear façade ornament; gold and white; Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) Kos, J., (1993): Umetniški paviljon