Guanajuato, 1766-1767

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism, Heritage and Creativity: Divergent Narratives and Cultural Events in Mexican World Heritage Cities

Tourism, Heritage and Creativity: Divergent Narratives and Cultural Events in Mexican World Heritage Cities Tourismus, Erbe und Kreativität: Divergierende Erzählungen und kulturelle Ereignisse in mexi-kanischen Weltkulturerbe-Städten MARCO HERNÁNDEZ-ESCAMPA, DANIEL BARRERA-FERNÁNDEZ** Faculty of Architecture “5 de Mayo”, Autonomous University of Oaxaca “Benito Juárez” Abstract This work compares two major Mexican events held in World Heritage cities. Gua- najuato is seat to The Festival Internacional Cervantino. This festival represents the essence of a Mexican region that highlights the Hispanic past as part of its identity discourse. Meanwhile, Oaxaca is famous because of the Guelaguetza, an indigenous traditional festival whose roots go back in time for fve centuries. Focused on cultural change and sustainability, tourist perception, identity narrative, and city theming, the analysis included anthropological and urban views and methodologies. Results show high contrasts between the analyzed events, due in part to antagonist (Indigenous vs. Hispanic) identities. Such tension is characteristic not only in Mexico but in most parts of Latin America, where cultural syncretism is still ongoing. Dieser Beitrag vergleicht Großveranstaltungen zweier mexikanischer Städte mit Welt- kulturerbe-Status. Das Festival Internacional Cervantino in Guanajato steht beispiel- haft für eine mexikanische Region, die ihre spanische Vergangenheit als Bestandteil ihres Identitätsdiskurses zelebriert. Oaxaca wiederum ist für das indigene traditionelle Festival Guelaguetza bekannt, dessen Vorläufer 500 Jahre zurückreichen. Mit einem Fokus auf kulturellen Wandel und Nachhaltigkeit, Tourismus, Identitätserzählungen und städtisches Themenmanagement kombiniert die Analyse Perspektiven und Me- thoden aus der Anthropologie und Stadtforschung. Die Ergebnisse zeigen prägnante Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Festivals auf, die sich u.a. auf antagonistische Iden- titäten (indigene vs. -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

Periodico Oficial Del Gobierno Del Estado De Guanajuato

PERIODICO OFICIAL DEL GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE GUANAJUATO Fundado el 14 de Enero de 1877 Registrado en la Administración de Correos el 10. de Marzo de 1924 AÑO CVIII GUANAJUATO, GTO., A 15 DE FEBRERO DEL 2021 NUMERO 32 TOMO CLVIX SEGUNDA PARTE SUMARIO GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO - PODER LEGISLATIVO DECRETO Legislativo 306 por el cual se reforma el artículo 240 de la Ley Orgánica Municipal para el Estado de Guanajuato....... ............... ............. ............. ............. ............. ......... 4 DECRETO Legislativo 307 por el cual se adicionan al artículo 125 un párrafo segundo y al artículo 153 un párrafo segundo de la Ley Orgánica Municipal para el Estado de Guanajuato. 6 SECRETARíA DE FINANZAS, INVERSiÓN Y ADMINISTRACiÓN ACUERDO por el que se da a conocer a los Municipio del estado de Guanajuato el calendario de entrega, porcentajes, fórmulas y variables utilizadas, así como los montos estimados de participaciones estimadas para el ejercicio fiscal 2021. ...... ......... ......... ......... ......... ......... 9 PODER JUDICIAL DEL ESTADO DE GUANAJUATO CERTIFICACiÓN del Acuerdo número II del Consejo del Poder Judicial del Estado Guanajuato, por el que se asumen acciones derivadas de la permanencia del semáforo rojo, anunciado por la Autoridad de Salud, a partir del 12 de febrero de 2021.. ..... ... ..... ... ..... ........ ........ ..... 56 SECRETARíA DE INFRAESTRUCTURA, CONECTIVIDAD Y MOVILIDAD DEL ESTADO DE GUANAJUATO EDICTO emitido por la Dirección General de Servicios Jurídicos de la Secretaría de Infraestructura, Conectividad y Movilidad del Estado de Guanajuato, a fin de dar a conocer la terminación anticipada del contrato público número SICOM/RE/AM/PU/DPI/SERV/OP/2020- 0243, celebrado con la persona física Ignacio Maldonado Rodríguez, para el "Proyecto ejecutivo de la rehabilitación del cuerpo central y calles laterales del acceso sur de Celaya (Incluye colector pluvial), tramo Libramiento Sur de Celaya - Avenida Constituyentes.", para quienes se crean con derecho y así lo acrediten, se opongan a la presente determinación. -

El PINGUICO NI43-101

NI 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT FOR EL PINGUICO PROJECT GUANAJUATO MINING DISTRICT, MEXICO Guanajuato City, Guanajuato State Mexico Nearby Central coordinates 20°58' Latitude N, 101°13' longitude W Prepared for VANGOLD RESOURCES LTD. 1780-400 Burrard Street Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 3A6 Report By: Carlos Cham Domínguez, C.P.G. Consulting Geological Engineer Effective Date: February 28, 2017 1 DATE AND SIGNATURE PAGE AUTHOR CERTIFICATION I, Carlos Cham Domínguez, am Certified Professional Geologist and work for FINDORE S.A. DE C.V. located at Marco Antonio 100, col. Villa Magna, San Luis Potosi, S.L.P., Mexico 78210. This certificate applies to the technical report entitled NI 43-101 Technical Report for El Pinguico Project, Guanajuato Mining District, Mexico, with an effective date of February 28, 2017. I am a Certified Professional Geologist in good standing with the American Institute of Professional Geologists (AIPG) with registration number CPG-11760. I graduated with a bachelor degree in Geology from the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí (Mexico) in 2003. I graduated with a MBA (finance) degree from the Universidad Tec Milenio (Mexico) in 2012 and I have a diploma in Mining and Environment from the University Miguel de Cervantes (Spain) in 2013. I have practiced my profession continuously for 13 years and have been involved in: mineral exploration and mine geology on gold and silver properties in Mexico. As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43-101. I visited the El Pinguico Project between the 2nd and 5th of January, 2017. -

11GU2020I0024.Pdf

EL CONTENIDO DE ESTE ARCHIVO NO PODRÁ SER ALTERADO O MODIFICADO TOTAL O PARCIALMENTE, TODA VEZ QUE PUEDE CONSTITUIR EL DELITO DE FALSIFICACIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS DE CONFORMIDAD CON EL ARTÍCULO 244, FRACCIÓN III DEL CÓDIGO PENAL FEDERAL, QUE PUEDE DAR LUGAR A UNA SANCIÓN DE PENA PRIVATIVA DE LA LIBERTAD DE SEIS MESES A CINCO AÑOS Y DE CIENTO OCHENTA A TRESCIENTOS SESENTA DÍAS MULTA. DIRECION GENERAL DE IMPACTO Y RIESGO AMBIENTAL PLANTA RECICLADORA DE ACEITE MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO USADO NO LUBRICANTE AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD PARTICULAR DISTRIBUIDORA JP, S.A. DE C.V. JARAL DEL PROGRESO, GTO. CAPITULO I I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL I.1 Proyecto I.1.1 Nombre del Proyecto. Planta Recicladora de Aceite Usado no Lubricante I.1.2 Ubicación del Proyecto Este proyecto se encontrará ubicado en Rancho La Mora, Km. 2.5 Carr. Jaral- Cortazar, municipio de Jaral del Progreso Guanajuato, C.P. 38470. VER ANEXO 1 El municipio de Jaral del Progreso está situado en la región IV Sureste del Estado de Guanajuato, entre las coordenadas 20° 15’ 08” y 20° 26’ 03”de latitud Norte, y entre los 100° 59’ 01” y los 101° 07’ 00” de longitud Oeste. La altitud promedio en el municipio es de 1730 msnm. 1 PLANTA RECICLADORA DE ACEITE MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO USADO NO LUBRICANTE AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD PARTICULAR DISTRIBUIDORA JP, S.A. DE C.V. JARAL DEL PROGRESO, GTO. El municipio se localiza en la parte centro-sur del estado, limita al norte, este y noreste con el municipio de Cortazar, al sur y suroeste con el de Yuriria; al sur, este y sureste con el de Salvatierra y al norte, oeste y noroeste con el de Valle de Santiago. -

Periodico Oficial Del Gobierno Del Estado De Guanajuato

PERIODICO OFICIAL DEL GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE GUANAJUATO Fundado el 14 de Enero de 1877 Registrado en la Administración de Correos el 10. de Marzo de 1924 AÑO CVIII GUANAJUATO, GTO., A 20 DE ENERO DEL 2021 NUMERO 14 TOMO CLVIX SEGUNDA PARTE SUMARIO PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL - CORONEO, GTO. SEXTA Modificación al Pronóstico de Ingresos, Presupuesto de Egresos y Plantilla de Personal de la Administración Pública del Municipio de Coroneo, Gto., para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2020. ................................................................................................................... 2 PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL - DOLORES HIDALGO CUNA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA NACIONAL, GTO. PRIMERA Modificación al Pronóstico de Ingresos y Presupuesto de Egresos para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2020 del Instituto Municipal de la Vivienda de Dolores Hidalgo Cuna de la Independencia Nacional, Guanajuato. ........................................................................ 4 PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL - LEÓN, GTO. PERMISO de Venta que emite la Dirección General de Desarrollo Urbano del municipio de León, Guanajuato; para la sección 4 del fraccionamiento mixto denominado Jardines del Rio, de esa ciudad; documento remitido por la Dirección General de Desarrollo Urbano del municipio de León, Gto. ......................... ....................................... ........................... 7 PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL - SAN LUIS DE LA PAZ, GTO. PRESUPUESTO de Egresos de la Administración Pública Municipal de San Luis de la Paz, Guanajuato, para el ejercicio fiscal 2021. ......... .......... -

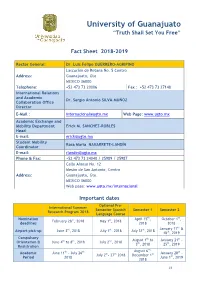

University of Guanajuato “Truth Shall Set You Free”

University of Guanajuato “Truth Shall Set You Free” Fact Sheet 2018-2019 Rector General: Dr. Luis Felipe GUERRERO-AGRIPINO Lascuráin de Retana No. 5 Centro Address: Guanajuato, Gto. MEXICO 36000 Telephone: +52 473 73 20006 Fax : +52 473 73 27148 International Relations and Academic Dr. Sergio Antonio SILVA-MUÑOZ Collaboration Office Director E-Mail : [email protected] Web Page: www.ugto.mx Academic Exchange and Mobility Department Erick M. SÁNCHEZ-ROBLES Head E-mail: [email protected] Student Mobility Rosa María NAVARRETE-LANDÍN Coordinator E-mail: [email protected] Phone & Fax: +52 473 73 24040 / 25989 / 25987 Calle Alonso No. 12 Mesón de San Antonio, Centro Address: Guanajuato, Gto. MEXICO 36000 Web page: www.ugto.mx/internacional Important dates Optional Pre- International Summer Semester Spanish Semester 1 Semester 2 Research Program 2018 Language Course Nomination April 15th, October 1st, February 28th, 2018 May 1st, 2018 deadlines 2018 2018 January 17th & Airport pick-up June 3rd, 2018 July 1st, 2018 July 31st, 2018 18th, 2019 Compulsory August 1th to January 21st – Orientation & June 4th to 8th, 2018 July 2nd, 2018 3th, 2018 25th, 2019 Registration August 6th- Academic June 11th – July 26th January 28th – July 2th- 27th 2018 December 1st Period 2018 June 1st, 2019 2018 1/5 Final December 3th – June 3th – 7th, July 27th, 2018 July 27th, 2018 Evaluation 7th, 2018 2019 Regular fee 2017: Fees Scholarships may apply Tuition waiver Tuition waiver 780USD Academic Information International Summer Research Program o Research project conducted in English or French o 10 week program with host family accommodation o Research project to be presented in a national congress under supervision of a researcher. -

Juan De Flandes and His Financial Success in Castile

Volume 11, Issue 1 (Winter 2019) Juan de Flandes and His Financial Success in Castile Jessica Weiss [email protected] Recommended Citation: Jessica Weiss, “Juan de Flandes and His Financial Success in Castile,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 11:1 (Winter 2019) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2019.11.1.2 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/juan-de-flandes-and-his-financial-success-in-castile/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 Juan de Flandes and His Financial Success in Castile Jessica Weiss During the late fifteenth century, the Netherlandish painter Juan de Flandes traveled to the court of Isabel, queen of Castile and León. He remained in her service until her death and subsequently secured multiple commissions for contributions to large-scale altarpiece projects. The financial documents associated with his career and his works reveal a high level of economic success in comparison to other artists active in Castile, including his fellow court painter Michel Sittow. This investigation into the fiscal opportunities available to a Netherlandish émigré demonstrates the economic power of locally produced Flemish art in sixteenth-century Iberia.. 1 The Netherlandish painter Juan de Flandes (active 1496–1519) had a lucrative career on the Iberian Peninsula, and his professional history serves as an important case study on the economic motivations for immigrant artists.1 He first appears in 1496 in the court documents of Isabel, queen of Castile and León (1451–1504), and he used his northern European artistic training to satisfy the queen’s demand for Netherlandish-style panel paintings. -

Constructing 'Race': the Catholic Church and the Evolution of Racial Categories and Gender in Colonial Mexico, 1521-1700

CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 i CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of the Catholic Church in defining racial categories and construction of the social order during and after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, then New Spain. The Catholic Church, at both the institutional and local levels, was vital to Spanish colonization and exercised power equal to the colonial state within the Americas. Therefore, its interests, specifically in connection to internal and external “threats,” effected New Spain society considerably. The growth of Protestantism, the Crown’s attempts to suppress Church influence in the colonies, and the power struggle between the secular and regular orders put the Spanish Catholic Church on the defensive. Its traditional roles and influence in Spanish society not only needed protecting, but reinforcing. As per tradition, the Church acted as cultural center once established in New Spain. However, the complex demographic challenged traditional parameters of social inclusion and exclusion which caused clergymen to revisit and refine conceptions of race and gender. -

Where Nomads Go Need to Know to Need

Art & Cities Nature 1 Welcome Culture & Towns & Wildlife Adventure Need to Know worldnomads.com Where Nomads Go Nomads Where your way from coast to coast. the curl at Puerto Escondido, and eat the curl at Puerto Escondido, an ancient pyramid at Muyil, shoot Dive with manatees in Xcalak, climb MEXICO 2 worldnomads.com World Nomads’ purpose is to challenge Contents travelers to harness their curiosity, be Adam Wiseman WELCOME WELCOME 3 brave enough to find their own journey, and to gain a richer understanding of Essential Mexico 4 Spanning almost 760,000mi² (2 million km²), with landscapes themselves, others, and the world. that range from snow-capped volcanos to dense rainforest, ART & CULTURE 6 and a cultural mix that’s equally diverse, Mexico can’t be How to Eat Mexico 8 contained in a handful of pages, so we’re not going to try. The Princess of the Pyramid 14 Think of this guide as a sampler plate, or a series of windows into Mexico – a selection of first-hand accounts from nomads Welcome The Muxes of Juchitán de Zaragoza 16 who’ve danced at the festivals, climbed the pyramids, chased Beyond Chichén Itzá 20 the waves, and connected with the locals. Meeting the World’s Authority Join our travelers as they kayak with sea turtles and manta on Mexican Folk Art 24 rays in Baja, meet the third-gender muxes of Juchitán, CITIES & TOWNS 26 unravel ancient Maya mysteries in the Yucatán, and take a Culture Mexico City: A Capital With Charisma 28 crash course in mole-making in Oaxaca. -

2010 CEOCB Monografia Cueramaro.Pdf

Este libro se imprimió en Linotipográfica Dávalos Hermanos, S.A. de C.V. Paseo del Moral 117 Col. Jardines del Moral, León Gto., México Diseño: Betzabe Lorelay Muñoz Arbaiza Ileana Villanueva Gómez Cuidado de la Edición: Isauro Rionda Arreguín Asesor de la Secretaría Técnica de la Comisión Estatal del Bicentenario Salvador Meza López Publicaciones Edición Especial, 2010 Derechos reservados de esta edición: © Gobierno del Estado de Guanajuato Secretaria Técnica Campanero No.6, Zona Centro, C.P.36000 Guanajuato, Guanajuato. México. Impreso y hecho en México HORACIO OLMEDO CANCHOLA Nació en Cuerámaro, Gto., en 1949. Es arquitecto, maestro y doctor en Arquitectura por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Es profesor, asesor y tutor al nivel de Maestría y Doctorado en la Facultad de Arquitectura de la UNAM, así como coordinador y expositor en diversos diplomados en la División de Educación Continua de la misma Facultad. Imparte cátedra y es titular del Seminario de Titulación en la Universidad Marista. En el ámbito profesional ha ocupado diversos cargos, tanto en la iniciativa pública cuanto en la privada. Actualmente es Director General de A3P Arquitectura, S. A. de C. V. Ha dictado conferencias y es autor de diversos artículos, libros y apuntes académicos. “El pasado inmediato, el tiempo más modesto del verbo. Los exagerados —los años los desengañarán— le llaman a veces el pasado absoluto. Tampoco hay para qué exaltarlo como un pretérito perfecto. Ojalá, entre todos, logremos presentarlo algún día como un pasado definido.” ALFONSO REYES: EL PASADO INMEDIATO “Despertar a la historia significa adquirir conciencia de nuestra singularidad, momento de reposo reflexivo antes de entregarnos al hacer. -

La Familia Drug Cartel: Implications for U.S-Mexican Security

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues related to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrate- gic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of De- fense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip re- ports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army par- ticipation in national security policy formulation. LA FAMILIA DRUG CARTEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S-MEXICAN SECURITY George W. Grayson December 2010 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S.