AC18 Armscor History Extract the Will To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa's Defence Industry: a Template for Middle Powers?

UNIVERSITYOFVIRGINIALIBRARY X006 128285 trategic & Defence Studies Centre WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY University of Virginia Libraries SDSC Working Papers Series Editor: Helen Hookey Published and distributed by: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax: 02 624808 16 WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds National Library of Australia Cataloguirtg-in-Publication entry Mills, Greg. South Africa's defence industry : a template for middle powers? ISBN 0 7315 5409 4. 1. Weapons industry - South Africa. 2. South Africa - Defenses. I. Edmonds, Martin, 1939- . II. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. III. Title. 338.4735580968 AL.D U W^7 no. 1$8 AUTHORS Dr Greg Mills and Dr Martin Edmonds are respectively the National Director of the South African Institute of Interna tional Affairs (SAIIA) based at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Director: Centre for Defence and Interna tional Security Studies, Lancaster University in the UK. South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? 1 Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds Introduction The South African arms industry employs today around half of its peak of 120,000 in the 1980s. A number of major South African defence producers have been bought out by Western-based companies, while a pending priva tisation process could see the sale of the 'Big Five'2 of the South African industry. This much might be expected of a sector that has its contemporary origins in the apartheid period of enforced isolation and self-sufficiency. -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

NSIAD-98-176 China B-279891

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Joint Economic GAO Committee, U.S. Senate June 1998 CHINA Military Imports From the United States and the European Union Since the 1989 Embargoes GAO/NSIAD-98-176 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-279891 June 16, 1998 The Honorable James Saxton Chairman, Joint Economic Committee United States Senate Dear Mr. Chairman: In June 1989, the United States and the members of the European Union 1 embargoed the sale of military items to China to protest China’s massacre of demonstrators in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. You have expressed concern regarding continued Chinese access to foreign technology over the past decade, despite these embargoes. As requested, we identified (1) the terms of the EU embargo and the extent of EU military sales to China since 1989, (2) the terms of the U.S. embargo and the extent of U.S. military sales to China since 1989, and (3) the potential role that such EU and U.S. sales could play in addressing China’s defense needs. In conducting this review, we focused on military items—items that would be included on the U.S. Munitions List. This list includes both lethal items (such as missiles) and nonlethal items (such as military radars) that cannot be exported without a license.2 Because the data in this report was developed from unclassified sources, its completeness and accuracy may be subject to some uncertainty. The context for China’s foreign military imports during the 1990s lies in Background China’s recent military modernization efforts.3 Until the mid-1980s, China’s military doctrine focused on defeating technologically superior invading forces by trading territory for time and employing China’s vast reserves of manpower. -

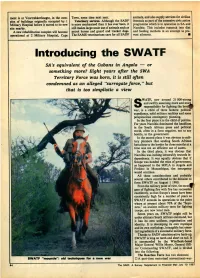

Introducing the SWATF

ment is at Voortrekkerhoogte, in the com Town, some time next year. animals, and also supply services for civilian plex of buildings originally occupied by 1 Veterinary services. Although the SADF livestock as part of the extensive civic action Military Hospital before it moved to its new is more mechanised than it has ever been, it programme which is in operation in SA and site nearby. still makes large-scale use of animals such as Namibia. This includes research into diet A new rehabilitation complex will become patrol horses and guard and tracker dogs. and feeding methods in an attempt to pre operational at 2 Military Hospital, Cape The SAMS veterinarians care for all SADF vent ailments. ■ Introducing the SWATF SA’s equivalent of the Cubans in Angola — or something more? Eight years after the SWA Territory Force was born, it is still often condemned as an alleged "surrogate force," but that is too simplistic a view WATF, now around 21 000-strong and swiftly assuming more and more S responsibility for fighting the bord(^ war, is a child of three fathers: political expediency, solid military realities and some perspicacious contingency planning. In the first place it is the child of politics. For years Namibia dominated the headlines in the South African press and political world, often in a form negative, not to say hostile, to the government. In the second place it was obvious to mili tary planners that sending South African battalions to the border for three months at a time was not an efficient use of assets. -

Civil-Military Relations in the MENA: Between Fragility and Resilience

CHAILLOT PAPER Nº 139 — October 2016 Civil-military relations in the MENA: between fragility and resilience BY Florence Gaub Chaillot Papers European Union Institute for Security Studies CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN THE MENA: BETWEEN FRAGILITY AND RESILIENCE Florence Gaub CHAILLOT PAPERS October 2016 139 The author Florence Gaub is a Senior Analyst at the EUISS where she works on the Middle East and North Africa and on security sector reform. In her focus on the Arab world she monitors post-conflict developments, Arab military forces, conflicts structures and geostrategic dimensions of the Arab region. European Union Institute for Security Studies Paris Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print: ISBN: 978-92-9198-502-9 ISSN: 1017-7566 doi:10.2815/359131 QN-AA-16-003-EN-C PDF: ISBN: 978-92-9198-501-2 ISSN: 1683-4917 doi:10.2815/567568 QN-AA-16-003-EN-N Contents Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli Introduction 7 1 Civil-military relations: the basics 9 2 Objective or subjective control? 13 3 Cooperation or distance? 25 4 Neutral or politicised? 29 5 Degrees of legitimacy 35 Conclusion 39 Annex 41 A Abbreviations 41 Foreword One of the key words (and concepts) of the freshly released EU Global Strategy (EUGS) is resilience. The term originates from medicine (patients who have suffered a severe trauma or illness need to become ‘resilient’ to its possible recurrence) as well as engineering (‘resilient’ materials are capable of absorbing stress and strain and even of bouncing back). -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

Airpower Journal: Fall 1987, Volume I, No. 2

. Aionrm*JCD, SPECIAL FOURTH CLASS MAIL '/uiin/rrui CALCULATED POSTAGE JOURNAL PERMITG-1 USAF-ECI MAXWELL AFB. AL 36112 GUNTER AFB, AL 36118 OFFICIAL BUSINESS PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300 RETURN POSTAGE GUARANTEED Secretary of the Air Force Edvvard C. Aldridge, Jr. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Larry D. Welch Commander, Air University Lt Gen Truman Spangrud Commander, Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Gol Sidney ). Wise Professional Staff Editor Col Keith VV. Geiger Associate Editor Maj Michael A. Kirtland Contributing Personnel Hugh Richardson, Associate Editor |ohn A. Westcott. Art Director and Production Manager Steven C. Garst. Illustrator Address manuscripls to Editor. Airpower /ournal, VValker Hall. Maxwell AFB. Alabama 36112-5532. Jour- nal telephone listings are AUTOVON 875-5322 and commercial 205-293-5322. Manuscripls should be typed, double-spaced, and submitted in duplicate. Au- thors should enclose a short biographical sketch indi- cating current and previous assignments. academic and professional military education. and other particulars. Printed by Government Printing Office. Subscription re- nuests and change of address notifications should be sent to: Superinlendent of Documents. US Government Print- ing Office. Washington. D.C. 20402, Air Force Recurring Publication 50-2. ISSN: 0002-2594. JOURNAL FALL 19 87 , Vol. 1, No. 2 AFRP 50-2 From the Editor 2 The Decade of Opportunity: Air Power in the 1990s AVM R. A. Mason. RAF 4 Doctrine, Technology, and Air Warfare: A Late Twentieth-Century Perspective Dr Richard P. Hallion 16 Coalition Air Defense in the Persian Gulf Lt Col Ronald C. Smith, USAF 28 Editorial—End of an Era Maj Michael A. -

Sanctuary Lost: the Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974

Sanctuary Lost: The Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Martin Hurley, MA Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Professor John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Alan Beyerchen Professor Ousman Kobo Copyright by Matthew Martin Hurley 2009 i Abstract From 1963 to 1974, Portugal and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) waged an increasingly intense war for the independence of ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, then a colony but today the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. For most of this conflict Portugal enjoyed virtually unchallenged air supremacy and increasingly based its strategy on this advantage. The Portuguese Air Force (Força Aérea Portuguesa, abbreviated FAP) consequently played a central role in the war for Guinea, at times threatening the PAIGC with military defeat. Portugal‘s reliance on air power compelled the insurgents to search for an effective counter-measure, and by 1973 they succeeded with their acquisition and employment of the Strela-2 shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile, altering the course of the war and the future of Portugal itself in the process. To date, however, no detailed study of this seminal episode in air power history has been conducted. In an international climate plagued by insurgency, terrorism, and the proliferation of sophisticated weapons, the hard lessons learned by Portugal offer enduring insight to historians and current air power practitioners alike. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide

WORLDWIDE EQUIPMENT GUIDE TRADOC DCSINT Threat Support Directorate DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Sep 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page Memorandum, 24 Sep 2001 ...................................... *i V-150................................................................. 2-12 Introduction ............................................................ *vii VTT-323 ......................................................... 2-12.1 Table: Units of Measure........................................... ix WZ 551........................................................... 2-12.2 Errata Notes................................................................ x YW 531A/531C/Type 63 Vehicle Series........... 2-13 Supplement Page Changes.................................... *xiii YW 531H/Type 85 Vehicle Series ................... 2-14 1. INFANTRY WEAPONS ................................... 1-1 Infantry Fighting Vehicles AMX-10P IFV................................................... 2-15 Small Arms BMD-1 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-17 AK-74 5.45-mm Assault Rifle ............................. 1-3 BMD-3 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-19 RPK-74 5.45-mm Light Machinegun................... 1-4 BMP-1 IFV..................................................... 2-20.1 AK-47 7.62-mm Assault Rifle .......................... 1-4.1 BMP-1P IFV...................................................... 2-21 Sniper Rifles..................................................... -

The Future of the Air Forces and Air Defence Units of Poland’S Armed Forces

The future of the Air Forces and air defence units of Poland’s Armed Forces ISBN 978-83-61663-05-8 The future of the Air Forces and air defence units of Poland’s Armed Forces Pulaski for Defence of Poland Warsaw 2016 Authors: Rafał Ciastoń, Col. (Ret.) Jerzy Gruszczyński, Rafał Lipka, Col. (Ret.) dr hab. Adam Radomyski, Tomasz Smura Edition: Tomasz Smura, Rafał Lipka Consultations: Col. (Ret.) Krystian Zięć Proofreading: Reuben F. Johnson Desktop Publishing: Kamil Wiśniewski The future of the Air Forces and air defence units of Poland’s Armed Forces Copyright © Casimir Pulaski Foundation ISBN 978-83-61663-05-8 Publisher: Casimir Pulaski Foundation ul. Oleandrów 6, 00-629 Warsaw, Poland www.pulaski.pl Table of content Introduction 7 Chapter I 8 1. Security Environment of the Republic of Poland 8 Challenges faced by the Air Defence 2. Threat scenarios and missions 13 System of Poland’s Armed Forces of Air Force and Air Defense Rafał Ciastoń, Rafał Lipka, 2.1 An Armed attack on the territory of Poland and 13 Col. (Ret.) dr hab. Adam Radomyski, Tomasz Smura collective defense measures within the Article 5 context 2.2 Low-intensity conflict, including actions 26 below the threshold of war 2.3 Airspace infringement and the Renegade 30 procedure 2.4 Protection of critical 35 infrastructure and airspace while facing the threat of aviation terrorism 2.5 Out-of-area operations 43 alongside Poland’s allies Chapter II 47 1. Main challenges for the 47 development of air force capabilities in the 21st century What are the development options 2. -

The Gulf Military Forces in an Era of Asymmetric War Oman

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -7325 • Fax: 1 (202) 457 -8746 Web: www.csis.org/burke The Gulf Military Forces in an Era of Asymmetric War Oman Anthony H. Cordesman Khalid R. Al -Rodhan Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy Visiting Fellow [email protected] [email protected] Working Draft for Review and Comments Revised: June 28, 2006 Cordesman & Al -Rodhan: The Gulf Military Forces in an Era of Asymmetric Wars Oman 6/28/06 Page 2 In troduction Oman is a significant military power by Gulf standards, although its strength lies more in the quality of its military manpower and training than its equipment strength and quality. It also occupies a unique strategic location in the lower Gulf. As Map 1 shows, Oman controls the Mussandam Peninsula, and its waters include the main shipping and tanker routes that move in and out of the Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz. Its base at Goat Island is almost directly opposite of Iran’s base and port a t Bahdar Abbas. Oman would almost certainly play a major role in any confrontation or clash between Iran and the Southern Gulf states. The Strait of Hormuz is the world's most important oil chokepoint, and the US Energy Information agency reports that some 17 million barrels of oil a day move through its shipping channels. These consist of 2 -mile wide channels for inbound and outbound tanker traffic, as well as a 2 -mile wide buffer zone. -

OE Threat Assessment: United Arab Emirates (UAE)

DEC 2012 OE Threat Assessment: United Arab Emirates (UAE) TRADOC G-2 Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) Complex Operational Environment and Threat Integration Directorate (CTID) [Type the author name] United States Army 6/1/2012 OE Threat Assessment: UAE Introduction The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is important because of its location near the Strait of Hormuz and its willingness to work with Western nations. The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow body of water that separates the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman, through which 20% of the world’s oil passes annually. The UAE, seven emirates that work under a federalist structure, also is an important hydrocarbon producer in its own right with the world’s seventh largest known oil reserves and the eleventh largest known natural gas fields. The UAE allows both the U.S. and France to operate military bases in the country from where the two countries support their military activities in Afghanistan and elsewhere in the Middle East. Political Seven former members of what was known in the 19th century as the Trucial or Pirate Coast currently comprise the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In order of size, the emirates are: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Umm al Qaywayn, Ajman, Al Fajayrah, and Ras al Khaymah. Ras al Khaymah joined the UAE in February 1972 after the other six states agreed on a federal constitution the year before. The UAE, with its capital in Abu Dhabi, is a federation with specified powers delegated to the central government and all other powers reserved to the emirates. Due to the prosperity of the country, most of its inhabitants are content with the current political system.