Vitis AI User Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

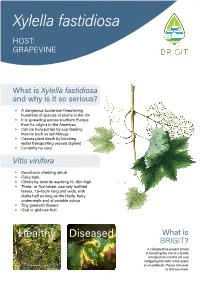

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

The Muscadine Grape (Vitis Rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C

HS763 The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C. Andersen, Ali Sarkhosh, Dustin Huff, and Jacque Breman2 Introduction from improved selections, and in fact, one that has been found in the Scuppernong River of North Carolina has The muscadine grape is native to the southeastern United been named ‘Scuppernong’. There are over 100 improved States and was the first native grape species to be cultivated cultivars of muscadine grapes that vary in size from 1/4 to in North America (Figure 1). The natural range of musca- 1 ½ inches in diameter and 4 to 15 grams in weight. Skin dine grapes extends from Delaware to central Florida and color ranges from light bronze to pink to purple to black. occurs in all states along the Gulf Coast to east Texas. It also Flesh is clear and translucent for all muscadine grape extends northward along the Mississippi River to Missouri. berries. Muscadine grapes will perform well throughout Florida, although performance is poor in calcareous soils or in soils with very poor drainage. Most scientists divide the Vitis ge- nus into two subgenera: Euvitis (the European, Vitis vinifera L. grapes and the American bunch grapes, Vitis labrusca L.) and the Muscadania grapes (muscadine grapes). There are three species within the Muscadania subgenera (Vitis munsoniana, Vitis popenoei and Vitis rotundifolia). Euvitis and Muscadania have somatic chromosome numbers of 38 and 40, respectively. Vines do best in deep, fertile soils, and they can often be found in adjacent riverbeds. Wild muscadine grapes are functionally dioecious due to incomplete stamen formation in female vines and incom- plete pistil formation in male vines. -

Sustainable Viticulture: Effects of Soil Management in Vitis Vinifera

agronomy Article Sustainable Viticulture: Effects of Soil Management in Vitis vinifera Eleonora Cataldo 1, Linda Salvi 1 , Sofia Sbraci 1, Paolo Storchi 2 and Giovan Battista Mattii 1,* 1 Department of Agriculture, Food, Environment and Forestry (DAGRI), University of Florence, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI), Italy; eleonora.cataldo@unifi.it (E.C.); linda.salvi@unifi.it (L.S.); sofia.sbraci@unifi.it (S.S.) 2 Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Research Centre for Viticulture and Enology (CREA-VE), 52100 Arezzo, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: giovanbattista.mattii@unifi.it; Tel.: 390-554-574-043 Received: 19 October 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 11 December 2020 Abstract: Soil management in vineyards is of fundamental importance not only for the productivity and quality of grapes, both in biological and conventional management, but also for greater sustainability of the production. Conservative soil management techniques play an important role, compared to conventional tillage, in order to preserve biodiversity, to save soil fertility, and to keep vegetative-productive balance. Thus, it is necessary to evaluate long-term adaptation strategies to create a balance between the vine and the surrounding environment. This work sought to assess the effects of following different management practices on Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon during 2017 and 2018 seasons: soil tillage (T), temporary cover cropping over all inter-rows (C), and mulching with plant residues every other row (M). The main physiological parameters of vines (leaf gas exchange, stem water potential, chlorophyll fluorescence, and indirect chlorophyll content) as well as qualitative and quantitative grape parameters (technological and phenolic analyses) were measured. -

Chemical Composition of Red Wines Made from Hybrid Grape and Common Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Cultivars

444 Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, 2014, 63, 4, 444–453 Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, 2014, 63, 4, 444–453 doi: 10.3176/proc.2014.4.10 Available online at www.eap.ee/proceedings Chemical composition of red wines made from hybrid grape and common grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivars Priit Pedastsaara*, Merike Vaherb, Kati Helmjab, Maria Kulpb, Mihkel Kaljurandb, Kadri Karpc, Ain Raald, Vaios Karathanose, and Tõnu Püssaa a Department of Food Hygiene, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Kreutzwaldi 58A, 51014 Tartu, Estonia b Department of Chemistry, Tallinn University of Technology, Akadeemia tee 15, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia c Department of Horticulture, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Kreutzwaldi 1, 51014 Tartu, Estonia d Department of Pharmacy, University of Tartu, Nooruse 1, 50411 Tartu, Estonia e Department of Dietetics and Nutrition, Harokopio University, 70 El. Venizelou Ave., Athens, Greece Received 21 June 2013, revised 8 May 2014, accepted 23 May 2014, available online 20 November 2014 Abstract. Since the formulation of the “French paradox”, red grape wines are generally considered to be health-promoting products rather than culpable alcoholic beverages. The total wine production, totalling an equivalent of 30 billion 750 mL bottles in 2009, only verifies the fact that global demand is increasing and that the polyphenols present in wines are accounting for a significant proportion of the daily antioxidant intake of the general population. Both statements justify the interest of new regions to be self-sufficient in the wine production. Novel cold tolerant hybrid grape varieties also make it possible to produce wines in regions where winter temperatures fall below – 30 °C and the yearly sum of active temperatures does not exceed 1750 °C. -

In Vitro Clonal Propagation of Grapevine (Vitis Spp.)

In vitro clonal Propagation of grapevine (Vitis spp.) By Magdoleen Gamar Eldeen Osman B.Sc. Agriculture Science (Honours) Sudan University of Science and Technology Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of science in Agric Supervisor :Prof.Abd El Gaffar Al Hag Said Co supervisor :Dr.Mustafa .M.El Balla Department of Horticulture Faculty of Agriculture University of Khartoum October 2oo4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication………………………………. Acknowledgment………………………….……… i Contents…………………………………………… ii Abstract……………………………………………. iv Arabic Abstract…………………………………… vi 1. Introduction ………………………………………. 1 2. Literature review………………………………… 3 2.1 Origin and distribution of grape (vitis sp)………. 3 2.2 Botany……………………………………………... 3 2.3 Soil and Location………………………………… 4 2.4 Yield and storage…………………………………. 4 2.5 Pests and diseases…………………………………. 2.6 World production………………………………… 2.7 Propagation methods…………………………… 7 2.7.1 Traditional propagation ………………………… 7 2.7.2 Propagation by tissue culture……………………. 8 2.7.2.1 The ex-plant……………………………………….. 9 2.7.2.2 Media composition ……………………………….. 11 2.7.2.2.1 Inorganic nutrients ……………………………… 11 2.7.2.2.2 Organic nutrien…………………………………… 13 2.7.2.2.2.1 Carbohydrates…………………………………… 14 2.7.2.2.2.2 Growth regulators………………………………… 15 3. Materials and methods…………………………… 19 3.1 Plant material……………………………………... 19 3.2 Sterilization……………………………………… 19 3.3 Preparation of ex-plants …………………………. 19 3.4 Basal nutrient medium…………………………… 20 3.5 Culture incubation……………………………….. 20 3.6 Experimentation………………………………….. 20 3.6.1 Effect of MS salts mix……………………………. 20 3.6.2 Effect of supplementary phosphate …………………….. 21 3.6.3 Effect of ex-plant……………………………. 21 3.6.4 Growth regulators………………………………… 21 3.6.4.1 Combined effect of kinetin annaphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) on 21 different growth parameters…… 3.6.4.2 Induction of roots…………………………………. -

Machine Vision for Ripeness Estimation in Viticulture Automation

horticulturae Review Machine Vision for Ripeness Estimation in Viticulture Automation Eleni Vrochidou , Christos Bazinas , Michail Manios, George A. Papakostas * , Theodore P. Pachidis and Vassilis G. Kaburlasos HUMAIN-Lab, Department of Computer Science, School of Sciences, International Hellenic University (IHU), 65404 Kavala, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.P.P.); [email protected] (V.G.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2510-462-321 Abstract: Ripeness estimation of fruits and vegetables is a key factor for the optimization of field management and the harvesting of the desired product quality. Typical ripeness estimation involves multiple manual samplings before harvest followed by chemical analyses. Machine vision has paved the way for agricultural automation by introducing quicker, cost-effective, and non-destructive methods. This work comprehensively surveys the most recent applications of machine vision techniques for ripeness estimation. Due to the broad area of machine vision applications in agriculture, this review is limited only to the most recent techniques related to grapes. The aim of this work is to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art algorithms by covering a wide range of applications. The potential of current machine vision techniques for specific viticulture applications is also analyzed. Problems, limitations of each technique, and future trends are discussed. Moreover, the integration of machine vision algorithms in grape harvesting robots for real-time in-field maturity assessment is additionally examined. Citation: Vrochidou, E.; Bazinas, C.; Manios, M.; Papakostas, G.A.; Keywords: machine vision; grape ripeness estimation; image analysis; precision agriculture; agrobots; Pachidis, T.P.; Kaburlasos, V.G. -

(Vitis Vinifera L.) Cultivars from Shoot and Leaf Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.6, No.23, 2016 Review on Invitro Regeneration of Some Selected Grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.) Cultivars from Shoot and Leaf Culture Fikadu Kumsa Department of Biology, College of Natural and Computational Science, Ambo University, Ethiopia Abstract Invitro regeneration is aseptic culture of cells, tissues, organs or whole plants under controlled nutritional and environmental conditions. Grapevine ( Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the most widely distributed fruit crops in the world. Conventional method of grapevine propagation is time consuming and allows disease transmission. A planted grape vine needs four to five years to be a propagation material by cutting, due to its long juvenility period. Therefore, the establishment of efficient in vitro regeneration is too much needed. The optimal levels of growth regulators and light conditions on callus induction and organogenesis of in-vitro cultured grapevine were assessed. Accordingly, maximum calluses and shoots were produced by using medium supplemented with different concentrations of growth regulators (BAP, IBA, TDZ and NAA) as alone or in combinations. For successful production of propagules, the occurrence and effect of in vitro shoot vetrification /hyperhydricity/were assessed. From the tested different concentrations of BAP and agar, the best mean numbers of vetrification free shoots were obtained at 0.5 mg/l BAP in 7.5g/l agar for both cheninblanc and canonannon cultivars. -

Tannin Content in Vitis Species Red Wines Quantified Using Three

molecules Article Tannin Content in Vitis Species Red Wines Quantified Using Three Analytical Methods Aude A. Watrelot Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Iowa State University, 536 Farm House Lane, Ames, IA 50011-1054, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-515-294-0343 Abstract: Tannin content in red wines is positively correlated with astringency perception and wine grade; however, tannin quantification is one of the main challenges. In this study, tannin content was quantified using three analytical methods in commercial red wines from Vitis vinifera and interspecific cold-hardy hybrids including Marquette, Frontenac, and Petite pearl cultivars. Protein (PP) and methylcellulose precipitation (MCP) methods were compared to a HPLC-DAD method, which is based on the interaction between tannins and a hydrophobic surface (RPC). Frontenac wines were the poorest in tannins and Cabernet sauvignon wines were the richest regardless of the method used. In cold-hardy red wines, the tannin content was higher in Marquette with high alcohol content, which suggested that the tannins were extracted from seeds rather than skins. The high limit of quantification of the PP method and the presence of anthocyanin di-glucosides in cold-hardy wines were parameters suggesting that protein and methylcellulose precipitation methods were neither suitable nor reliable for the quantification of tannins in cold-hardy red wines. The tannin content quantified by RPC was positively correlated to tannin quantified by MCP, suggesting that the RPC method would be relevant for the quantification of tannins in red wines. Citation: Watrelot, A.A. Tannin Keywords: proanthocyanidins; interspecific hybrid grapes; methylcellulose precipitation; protein Content in Vitis Species Red Wines precipitation; HPLC-PLRP Quantified Using Three Analytical Methods. -

Environmental Sources of Agrobacterium Vitis, the Cause Of

Environmental Sources of Agrobacterium vitis, the Cause of Crown Gall on Grape Tom Burr, Kameka Johnson, Cherie Reid, Didem CANIK Orel, Marcela Yepes, and Marc Fuchs Section of Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology, SIPS, Cornell University, NYSAES, Geneva, NY rown gall disease of grapes is caused by the bacterium, as a problem on Concord grapes, but is more prevalent in Niagara Agrobacterium vitis, and can significantly impact vine vineyards. In addition, grape rootstocks differ in susceptibility, growth and vineyard production. Although crown gall varying from highly susceptible to resistant. For example, crown C occurs on many gall is rarely seen on rootstocks C3309 and R. Gloire, but is more “We developed a highly sensitive method plant species, A. prevalent on rootstock 110-R. It should be noted that, because vitis is specific to the bacterium is systemic in vines, even resistant scion varieties for detecting the pathogen in grapevines grape, whereas and rootstocks may carry the pathogen internally. ... which is manyfold more sensitive other species of Because injuries are required for initiation of crown gall than previous detection methods ... and Agrobacterium infections, any management strategies that minimize injury and has greatly expanded our knowledge of c a u s e c r o w n particularly freeze injury will be of benefit. These include selec- where the bacterium persists in nature.” gall on different tion of planting sites that have good air drainage and are on well- crops, particularly drained soils. The disease is often first noted in low-lying regions fruits, nuts and of vineyards. These may have persistently wet soils, which affects o r n a m e n t a l s vine vigor and winter acclimation, and they are also locations where (Otten et al. -

Wild Grape (Vitis Spp.) & Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus Spp.) WILD GRAPE

Weed Identification and Control Sheet: www.goodoak.com/weeds Wild Grape (Vitis spp.) & Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus spp.) WILD GRAPE: There are four species of wild grape native to Wisconsin. The most common by far is riverbank grape (Vitis riparia), sometimes just called wild grape. It is a woody vine that rambles over shrubs and fencerows and can even climb into the tree canopy. Occasionally you will find summer grape (V. aestiva- lis). This species has a more variable leaf shape, with the underside of leaves being strongly whitened. Note that if you find a very aggressive grape-like woody vine, in may in-fact be porcelaine berry, a new invasive species that must be ag- gressively eliminated. Grapes certainly have value in the natural community. Their small, greenish-yellow flowers are very attractive to small bees.Their berries are a popular treat for songbirds, gamebirds and many mam- mals, including human foragers. Over 20 species of moth caterpillars feed on wild grape including the fascinating sphinx moths as do other insects, such as impressive grapevine beetle. These insects are then food for larger animals, making grapes an important cornerstone in the foundation of the ecosystem. VIRGINIA CREEPER: A native woody vine in the grape family, Virginia creeper has compound, five-lobed leaves which radiate out from a central point. They have small green flowers that are typically pollinated by small solitary bees. They have black berries that are not as palatable to hu- mans as grapes, but are still highly valued by wildlife. Nearly a dozen species of insects feed on the foliage, making Virginia creeper another important component of our ecological community. -

Evolutionary Genomics of Grape (Vitis Vinifera Ssp. Vinifera) Domestication

Evolutionary genomics of grape (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera) domestication Yongfeng Zhou (周永锋)a, Mélanie Massonnetb, Jaleal S. Sanjaka, Dario Cantub, and Brandon S. Gauta,1 aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697; and bDepartment of Viticulture and Enology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 Edited by Andrew G. Clark, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and approved September 25, 2017 (received for review June 5, 2017) We gathered genomic data from grapes (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera), a of slightly deleterious variants (14, 15). The characterization of clonally propagated perennial crop, to address three ongoing myster- deleterious variants is important because they may be fitting targets ies about plant domestication. The first is the duration of domestica- for crop improvement (16). Consistent with a cost of domestica- tion; archaeological evidence suggests that domestication occurs over tion, annual crops are known to contain an increase in derived, millennia, but genetic evidence indicates that it can occur rapidly. We putatively deleterious variants relative to their wild progenitors – estimated that our wild and cultivated grape samples diverged (17 20). However, it is not yet clear whether these deleterious ∼22,000 years ago and that the cultivated lineage experienced a variants increase genetic load and whether this phenomenon ap- steady decline in population size (Ne) thereafter. The long decline plies to perennial crops. may reflect low-intensity management by humans before domestica- The distinction between annual and perennial crops is crucial tion. The second mystery is the identification of genes that contribute because perennial domestication is expected to differ from annual to domestication phenotypes. -

Collecting Vitis Berlandieri from Native Habitat Sites

Collecting Vitis berlandieri from Native Habitat Sites Joachim Schmid,1 Frank Manty,1 and Peter Cousins*2 1Fachgebiet Rebenzüchtung und Rebenveredlung, Forschungsanstalt Geisenheim, Germany 2United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service 630 W. North Street, Geneva, NY 14456 email: [email protected] Lime content is the major difference between Northern American and European vine growing soils. This resulted in significant difficulties in the development of rootstocks for European conditions at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. It was only the introduction of Vitis berlandieri as a breeding partner that led to lime tolerant rootstocks. Despite this key role of V. berlandieri for European viticulture, only a few accessions have so far been used for breeding purposes. In most cases these vines were only used because they were available in Europe at this time. The genetic range of the species is certainly much larger and has so far not been utilized. To preserve and evaluate genetic diversity in V. berlandieri, grape berries were collected in September 2005 from a large range of natural stands in Texas, United States. 86 individual vines were sampled. The collection locations were found in thirteen counties and across a distribution from N 31° 23′ to N 29° 43′ and W 100° 2′ to W 97° 26′. Berries were sent to USDA, Geneva, NY and seeds collected and shipped to Geisenheim for germination. Vines will be planted in germplasm collections and evaluated for their rooting and grafting ability, their lime tolerance, and other viticultural features. Superior types will then be utilized in the Geisenheim rootstock breeding program.