Evolutionary Genomics of Grape (Vitis Vinifera Ssp. Vinifera) Domestication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

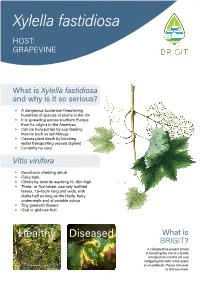

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

Grape Basics

Grape Basics s – any c ll grape olor – A vitamins C Shop and Save ntain and K co < For eating fresh, choose h help heal cu whic ts. table grapes. They have thinner skins and are sweet and juicy. Grapes grown for juice or wine have thicker skins and much Raisins more sugar. < Depending on the variety of < Look for firm, plump grapes grape, raisins (dried grapes) that are firmly attached to become dark brown or golden. green, flexible stems. < Look for tightly-sealed < Avoid grapes that are containers or covered bulk shriveled, sticky, have brown bins. Raisins should feel soft spots, or with dry, brittle and pliable. stems. < Store raisins in an airtight < Grapes are commonly purple, container in a cool, dry, dark red or pale green. They may place. be seedless or have seeds. Try < different colors, sizes and Once opened, reseal the textures by choosing the variety package tightly to help prevent that is lowest in price. hardening. For best quality use within 6 months. < If raisins become hard, soak in hot liquid for 5 to 15 minutes. Drain and use. < It takes 1 cup of grapes to make ¼ cup of raisins. They Store Well both have about 100 calories. Waste Less M Whole grapes are a I Leave grapes on the stem but remove any grapes that are serious choking hazard for shriveled, brown, or moldy. perforated plastic bag. For best children younger than four I Grapes can be kept on the quality, use within 7 to 10 days. years old. Cut grapes in countertop for a day or two, but I Rinse under cool water just half lengthwise or even last longer when refrigerated. -

So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee

Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee PB 1689 So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee 1 conditions. American grapes are So You Want to Grow versatile. They may be used for fresh consumption (table grapes) or processed into wine, juice, jellies or Grapes in Tennessee some baked products. Seedless David W. Lockwood, Professor grapes are used mostly for fresh Plant Sciences and Landscape Systems consumption, with very little demand for them in wines. Yields of seedless varieties do not match ennessee has a long history of grape production. Most recently, those of seeded varieties. They are T passage of the Farm Winery Act in 1978 stimuated an upsurge of also more susceptible to certain interest in grape production. If you are considering growing grapes, the diseases than the seeded American following information may be useful to you. varieties. French-American hybrids are crosses between American bunch 1. Have you ever grown winery, the time you spend visiting and V. vinifera grapes. Their grapes before? others will be a good investment. primary use is for wine. uccessful grape production Vitis vinifera varieties are used S requires a substantial commit- 3. What to grow for wine. Winter injury and disease ment of time and money. It is a American problems seriously curtail their marriage of science and art, with a - seeded growth in Tennessee. good bit of labor thrown in. While - seedless Muscadines are used for fresh our knowledge of how to grow a French-American hybrid consumption, wine, juice and jelly. crop of grapes continues to expand, Vitis vinifera Vines and fruits are not very we always need to remember that muscadine susceptible to most insects and some crucial factors over which we Of the five main types of grapes diseases. -

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • a GUIDE for PROSPECTIVE GROWERS •

Starting a Vineyard in Texas • A GUIDE FOR PROSPECTIVE GROWERS • Authors Michael C ook Viticulture Program Specialist, North Texas Brianna Crowley Viticulture Program Specialist, Hill Country Danny H illin Viticulture Program Specialist, High Plains and West Texas Fran Pontasch Viticulture Program Specialist, Gulf C oast Pierre Helwi Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Jim Kamas Associate Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist Justin S cheiner Assistant Professor and Extension Viticulture Specialist The Texas A&M University System Who is the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service? We are here to help! The Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service delivers research-based educational programs and solutions for all Texans. We are a unique education agency with a statewide network of professional educators, trained volunteers, and county offices. The AgriLife Viticulture and Enology Program supports the Texas grape and wine industry through technical assistance, educational programming, and applied research. Viticulture specialists are located in each region of the state. Regional Viticulture Specialists High Plains and West Texas North Texas Texas A&M AgriLife Research Denton County Extension Office and Extension Center 401 W. Hickory Street 1102 E. Drew Street Denton, TX 76201 Lubbock, TX 79403 Phone: 940.349.2896 Phone: 806.746.6101 Hill Country Texas A&M Viticulture and Fruit Lab 259 Business Court Gulf Coast Fredericksburg, TX 78624 Texas A&M Department of Phone: 830.990.4046 Horticultural Sciences 495 Horticulture Street College Station, TX 77843 Phone: 979.845.8565 1 The Texas Wine Industry Where We Have Been Grapes were first domesticated around 6 to 8,000 years ago in the Transcaucasia zone between the Black Sea and Iran. -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

The Story of Our Biodynamic Vineyard Biodynamics at Eco Terreno

The Story of Our Biodynamic Vineyard Biodynamics at Eco Terreno We staunchly believe that in order to become understanding of water usage to planting a successful grape growers and winemakers, we substantial bee garden, all of our work has must first create a healthy native ecosystem directly translated into us becoming more for our vineyards. In fact we’re so passionate informed stewards of our resources. In about being dedicated caretakers of the restoring the natural riparian areas on land that we named ourselves our property along the Russian “Great wines are not produced, Eco Terreno, which means “of River’s native wild habitats they are carefully cultivated.” the land” in Italian and “Land we are joining the cultivated Ecology in Spanish.” This and the non-cultivated lands passion has led to our transition together. We believe that by Mark Lyon, WINEMAKER to organic and biodynamic actively promoting biodiversity farming practices that are necessary to in our vineyards, we will explicitly becoming strong regenerative growers. From produce grapes and wine that reflect the planting cover crops to developing a holistic full expression of our terroir. The Biodynamic farming standard was the world’s first organic standard, started in 1928, by farmers in Austria and Germany. Today farmers in more than in 42 countries practice Biodynamic farming. how biodynamic is different Biodynamics is a holistic approach to farming In short, biodynamic viticulture takes us developed in the 1920’s as a response to the beyond organic farming, to a system where failures of chemical agriculture. Founded the subtle influences of the seasons, the by scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner, movement of the moon and planets, and the ancient practices were married with an dynamic interplay of life above and below understanding of chemistry and plant ground coalesces in the grapes grown and physiology to create a system that treats wines made. -

Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis Vinifera During Lasiodiplodia Theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis vinifera during Lasiodiplodia theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions Micael F. M. Gonçalves 1 , Rui B. Nunes 1, Laurentijn Tilleman 2 , Yves Van de Peer 3,4,5 , Dieter Deforce 2, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh 2, Ana C. Esteves 6 and Artur Alves 1,* 1 Department of Biology, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] (M.F.M.G.); [email protected] (R.B.N.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Campus Heymans, Ottergemsesteenweg 460, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (F.V.N.) 3 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, 9052 Ghent, Belgium 5 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 6 Faculty of Dental Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Estrada da Circunvalação, 3504-505 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-370-766 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: Lasiodiplodia theobromae is one of the most aggressive agents of the grapevine trunk disease Botryosphaeria dieback. Through a dual RNA-sequencing approach, this study aimed to give a broader perspective on the infection strategy deployed by L. theobromae, while understanding grapevine response. Approximately 0.05% and 90% of the reads were mapped to the genomes of L. -

Grape Growing

GRAPE GROWING The Winegrower or Viticulturist The Winegrower’s Craft into wine. Today, one person may fill both • In summer, the winegrower does leaf roles, or frequently a winery will employ a thinning, removing excess foliage to • Decades ago, winegrowers learned their person for each role. expose the flower sets, and green craft from previous generations, and they pruning, taking off extra bunches, to rarely tasted with other winemakers or control the vine’s yields and to ensure explored beyond their village. The Winegrower’s Tasks quality fruit is produced. Winegrowers continue treatments, eliminate weeds and • In winter, the winegrower begins pruning • Today’s winegrowers have advanced trim vines to expose fruit for maximum and this starts the vegetative cycle of the degrees in enology and agricultural ripening. Winegrowers control birds with vine. He or she will take vine cuttings for sciences, and they use knowledge of soil netting and automated cannons. chemistry, geology, climate conditions and indoor grafting onto rootstocks which are plant heredity to grow grapes that best planted as new vines in the spring, a year • In fall, as grapes ripen, sugar levels express their vineyards. later. The winegrower turns the soil to and color increases as acidity drops. aerate the base of the vines. The winegrower checks sugar levels • Many of today’s winegrowers are continuously to determine when to begin influenced by different wines from around • In spring, the winegrower removes the picking, a critical decision for the wine. the world and have worked a stagé (an mounds of earth piled against the base In many areas, the risk of rain, hail or apprenticeship of a few months or a of the vines to protect against frost. -

The Muscadine Grape (Vitis Rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C

HS763 The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx)1 Peter C. Andersen, Ali Sarkhosh, Dustin Huff, and Jacque Breman2 Introduction from improved selections, and in fact, one that has been found in the Scuppernong River of North Carolina has The muscadine grape is native to the southeastern United been named ‘Scuppernong’. There are over 100 improved States and was the first native grape species to be cultivated cultivars of muscadine grapes that vary in size from 1/4 to in North America (Figure 1). The natural range of musca- 1 ½ inches in diameter and 4 to 15 grams in weight. Skin dine grapes extends from Delaware to central Florida and color ranges from light bronze to pink to purple to black. occurs in all states along the Gulf Coast to east Texas. It also Flesh is clear and translucent for all muscadine grape extends northward along the Mississippi River to Missouri. berries. Muscadine grapes will perform well throughout Florida, although performance is poor in calcareous soils or in soils with very poor drainage. Most scientists divide the Vitis ge- nus into two subgenera: Euvitis (the European, Vitis vinifera L. grapes and the American bunch grapes, Vitis labrusca L.) and the Muscadania grapes (muscadine grapes). There are three species within the Muscadania subgenera (Vitis munsoniana, Vitis popenoei and Vitis rotundifolia). Euvitis and Muscadania have somatic chromosome numbers of 38 and 40, respectively. Vines do best in deep, fertile soils, and they can often be found in adjacent riverbeds. Wild muscadine grapes are functionally dioecious due to incomplete stamen formation in female vines and incom- plete pistil formation in male vines. -

VITICULTURE and ENOLOGY RESOURCE GUIDE

VITICULTURE and ENOLOGY RESOURCE GUIDE VITICULTURE ONLINE RESOURCES Napa County UCCE - Viticulture Home Page. Use for access to: http://ucanr.org/sites/NapaCountyUCCE/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/# 1. Growing Grapes (table, wine, raisins) in Your Backyard http://ucanr.edu/sites/gardenweb/Growing_Grapes_in_the_California_Garden/# 2. UC Integrated Grape Team of Napa Co. Intake Form http://ucce.ucdavis.edu/survey/survey.cfm?surveynumber=8328 3. UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines - Grape Pests http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/selectnewpest.grapes.html 4. European Grapevine Moth http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/European_Grapevine_Moth/ 5. Vine Mealybug http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Vine_Mealybug/# 6. Argentine Ants http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Argentine_ants/# 7. Berry Shrivel http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Berry_Shrivel/# 8. Mystery Disease http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Mystery_Disease/# 9. Frost Protection http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Frost_Protection/# 10. Irrigation http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Viticulture/Irrigation/# 11. Sample Costs to Establish a Vineyard and Produce http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/files/52946.pdf Winegrapes 12. Weed Science http://cenapa.ucanr.edu/Napa_County_Programs/Weed_Science/ UC Integrated Viticulture - Use for finding publications, video http://iv.ucdavis.edu/ seminars, and useful links on relevant topics from research by the University of California. -

Grape Information Sheet

Grape Information Sheet Purchasing Specifications Bunch Size Specifications should state grade and color. Individual bunches should Measure Minimum be full. Grapes should be plump and firmly attached to green pliable Small Under 3/4 LB stems, and grapes should be uniform in size and seedless. No more than Medium 3/4 to 1 1/4 LB 12% should have defects that make grapes unusable, and no more than Large Over 1 1/24 LB 1% should be affected by decay. U.S. Grades • U.S. Extra Fancy Table - 90% of grapes must meet minimum size (11/16” or 13/16” depending on variety) • U.S. Fancy Table - 90% of grapes must meet minimum size (11/16” or 12/16” depending on variety) • U.S. No. 1 Table* - 75% of grapes must meet minimum size (9/16” or 10/16” depending on variety) • U.S. No. 1 Institutional - 75% of grapes must meet minimum size (9/16” or 10/16” depending on variety) *U.S. No. 1 Table Grapes consist of bunches of grapes of one variety, except when designated as assorted varieties. U.S. No. 1 Table Grapes are mature and fairly well colored. The berries are firm, firmly attached to capstems, and not split, shattered, crushed, dried, or wet. Grapes are free from decay, waterberry and sunburn, and should not be damaged by any other cause. Stems should not be dry and brittle. Stems should be free from mold and decay and not damaged by freezing or any other cause. Color Requirements • Red and black grapes have a minimum color requirement depending on grade. -

Sustainable Viticulture: Effects of Soil Management in Vitis Vinifera

agronomy Article Sustainable Viticulture: Effects of Soil Management in Vitis vinifera Eleonora Cataldo 1, Linda Salvi 1 , Sofia Sbraci 1, Paolo Storchi 2 and Giovan Battista Mattii 1,* 1 Department of Agriculture, Food, Environment and Forestry (DAGRI), University of Florence, 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI), Italy; eleonora.cataldo@unifi.it (E.C.); linda.salvi@unifi.it (L.S.); sofia.sbraci@unifi.it (S.S.) 2 Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Research Centre for Viticulture and Enology (CREA-VE), 52100 Arezzo, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: giovanbattista.mattii@unifi.it; Tel.: 390-554-574-043 Received: 19 October 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 11 December 2020 Abstract: Soil management in vineyards is of fundamental importance not only for the productivity and quality of grapes, both in biological and conventional management, but also for greater sustainability of the production. Conservative soil management techniques play an important role, compared to conventional tillage, in order to preserve biodiversity, to save soil fertility, and to keep vegetative-productive balance. Thus, it is necessary to evaluate long-term adaptation strategies to create a balance between the vine and the surrounding environment. This work sought to assess the effects of following different management practices on Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon during 2017 and 2018 seasons: soil tillage (T), temporary cover cropping over all inter-rows (C), and mulching with plant residues every other row (M). The main physiological parameters of vines (leaf gas exchange, stem water potential, chlorophyll fluorescence, and indirect chlorophyll content) as well as qualitative and quantitative grape parameters (technological and phenolic analyses) were measured.