V5. Wint-Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seismic Philately

Seismic Philately adapted from the 2008 CUREE Calendar introduction by David J. Leeds © 2007 - All Rights Reserved. Stamps shown on front cover (left to right): • Label created by Chicago businessmen to help raise relief for the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1944 San Juan, Argentina Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1954 Orleansville, Algeria Earthquake • Stamp commemorating the 1953 Zante, Greece Earthquake • Stamp from 75th Anniversary stamp set commemorating the 1931 Hawkes Bay, New Zealand Earthquake • Stamp depicting a lake formed by a landslide triggered by the 1923 Kanto, Japan Earthquake Consortium of Universities for Research in Earthquake Engineering 1301 South 46th Street, Richmond, CA 94804-4600 tel: 510-665-3529 fax: 510-665-3622 CUREE http://www.curee.org Seismic Philately by David J. Leeds Introduction Philately is simply the collection and the study of postage stamps. Some of the Secretary of the Treasury, and as a last resort, bisected stamps could stamp collectors (philatelists) collect only from their native country, others be used for half their face value. (see March) collect from the stamp-issuing countries around the world. Other philately collections are defined by topic, such as waterfalls, bridges, men with beards, FDC, first day cover, or Covers, are sometimes created to commerate the nudes, maps, flowers, presidents, Americans on foreign stamps, etc. Many first day a new stamp is issued. As part of the presentation, an envelope of the world’s stamps that are related to the topic of earthquakes have been with the new postage stamp is cancelled on the first day of issue. Additional compiled in this publication. -

Chartrand Madeleine J O 201

Gendered Justice: Women Workers, Gender, and Master and Servant Law in England, 1700-1850 Madeleine Chartrand A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University Toronto, Ontario September 2017 © Madeleine Chartrand, 2017 ii Abstract As England industrialized in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, employment relationships continued to be governed, as they had been since the Middle Ages, by master and servant law. This dissertation is the first scholarly work to conduct an in-depth analysis of the role that gender played in shaping employment law. Through a qualitative and quantitative examination of statutes, high court rulings, and records of the routine administration of the law found in magistrates’ notebooks, petty sessions registers, and lists of inmates in houses of correction, the dissertation shows that gendered assumptions influenced the law in both theory and practice. A tension existed between the law’s roots in an ideology of separate spheres and the reality of its application, which included its targeted use to discipline a female workforce that was part of the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution. A close reading of the legislation and judges’ decisions demonstrates how an antipathy to the notion of women working was embedded in the law governing their employment relationships. An ideological association of men with productivity and women with domesticity underlay both the statutory language and key high court rulings. Therefore, although the law applied to workers of both sexes, women were excluded semantically, and to some extent substantively, from its provisions. -

Jamaica-Wikipedia-Re

4/15/2017 Jamaica Wikipedia Coordinates: 18°N 77°W Jamaica From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia i Jamaica ( /dʒәˈmeɪkә/) is an island country situated in the Jamaica Caribbean Sea, consisting of the thirdlargest island of the Greater Antilles. The island, 10,990 square kilometres (4,240 sq mi) in area, lies about 145 kilometres (90 mi) south of Cuba, and 191 kilometres (119 mi) west of Hispaniola (the island containing the nationstates of Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Jamaica is the fourthlargest island country in the Caribbean, by area.[6] Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Out of Many, One People" Inhabited by the indigenous Arawak and Taíno peoples, the island came under Spanish rule following the arrival of Anthem: Christopher Columbus in 1494. Many of the indigenous people "Jamaica, Land We Love" died of disease, and the Spanish imported African slaves as 0:00 MENU labourers. Named Santiago, the island remained a possession of Royal anthem: "God Save the Queen" Spain until 1655, when England (later Great Britain) conquered it and renamed it Jamaica. Under British colonial rule Jamaica became a leading sugar exporter, with its plantation economy highly dependent on slaves imported from Africa. The British fully emancipated all slaves in 1838, and many freedmen chose to have subsistence farms rather than to work on plantations. Beginning in the 1840s, the British imported Chinese and Indian indentured labour to work on plantations. The island achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 6 August 1962.[7] With 2.8 million people, Jamaica is the thirdmost populous Anglophone country in the Americas (after the United States and Canada), and the fourthmost populous country in the Caribbean. -

ABSTRACT a Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment

1 ABSTRACT A Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment of the Norman Manley International Airport and its Access Route Kevin Patrick Douglas M.Sc. in Disaster Management The University of the West Indies 2011 The issue of disaster risk reduction through proper assessment of vulnerability has emerged as a pillar of disaster management, a paradigm shift from simply responding to disasters after they have occurred. The assessment of vulnerability is important for countries desiring to maintain sustainable economies, as disasters have the potential to disrupt their economic growth and the lives of thousands of people. This study is a preliminary assessment of the hazard vulnerabilities the Norman Manley International Airport (NMIA) in Kingston Jamaica and its Access Route, as these play an important developmental role in the Jamaican society. The Research involves an analysis of the hazard history of the area along with the location and structural vulnerabilities of critical facilities. Finally, the mitigation measures in place for the identified hazards are assessed and recommendations made to increase the resilience of the facility. The findings of the research show that the NMIA and its access route are mostly vulnerable to earthquakes, hurricanes with flooding from storm surges, wind damage and sea level rise based 2 on their location and structure. The major mitigation measures involved the raising of the Access Route from Harbour View Roundabout to the NMIA and implementation of structural protective barriers as well as various engineering design specifications of the NMIA facility. Also, the implementation of structural mitigation measures may be of limited success, if hazard strikes exceed the magnitude which they are designed to withstand. -

Jamaica Country Document on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2014

Jamaica Country Document on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2014 Prepared by: Disaster Risk Reduction Centre (DRRC) University of the West Indies December 5, 2014 Jamaica Country Document on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2014 December 2014 Office of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Management (ODPEM) National coordination: Office of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Management (ODPEM) Mr. Richard Thompson, Director General (acting) Ms. Michelle Edwards, Senior Director Preparedness and Emergency Operations Ms. Anna Tucker, Disaster Risk Management Specialist Regional coordination: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Alexc ia Cooke & Sandra Amlang Authors: Disaster Risk Reduction Centre (DRRC) University of West of Indies Dr. Barbara Carby Mr. Dorlan Burrell Mrs. Cleonie Samuels-Williams Proof Readers Dr. Barbara Carby Mr. Craig Williams Cover page design : Maria Camila García Ruiz This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the Europe an Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. ECHO U&ISDR European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Civil Protection department Reduction Regional office for the Caribbean Regional office for the Americas Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Ciudad del Saber (Clayton) , Panamá Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] URL: http://ec.europa.eu/echo/ URL: http://www.eird.org/ http://www.dipecholac.net/ http://www.unisdr.org/americas ii Table of Contents Pages i. List of Figures vi-vii ii. List of Tables vii-viii iii. -

The Jamaican Crime Problem: Peace Building and Community Action

CgCED CARIBBEAN GROUP FOR COOPERATION IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CONTROLLING THE JAMAICAN CRIME PROBLEM: PEACE BUILDING AND COMMUNITY ACTION DISCUSSION DRAFT Anthony Harriott Department of Government The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus CONTROLLING THE JAMAICAN CRIME PROBLEM: PEACE BUILDING AND COMMUNITY ACTION June 2000 Department of Government The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus Table Of Contents Page No. 1. Introduction............................................................................................1 2. Defining the Problem.............................................................................3 3. Sources of High Rate of Violent Crime.................................................12 4. Constraints on the Development of Policy ...........................................16 5. Some Possible Initiatives.......................................................................19 6. Community Crime Control and Peace Building...................................20 7. Community control and Reform of the Criminal Justice System.........22 8. Order in Public Places ..........................................................................26 9. Implementation Strategies.....................................................................28 10. Conclusion ...........................................................................................29 11. Endnotes...............................................................................................30 12. References ............................................................................................31 -

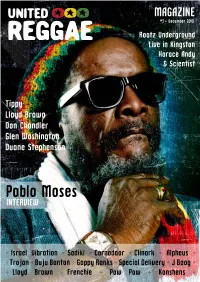

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

RESOLVING POVERTY in the CARIBBEAN 1 Akilah Jones

RESOLVING POVERTY IN THE CARIBBEAN 1 Akilah Jones Introduction The Caribbean Sea has a host of islands that are adjacent to the Americas; it is full of nation states more or less developed. Haiti and Jamaica are the poorest nations in the Caribbean; the wealthiest are Trinidad and Tobago, The Bahamas, and Puerto Rico. Environmental issues and natural disasters are some of the continuous battles that these nations have faced, but some have found ways to cultivate their land and rise above these issues that plague them. Hurricanes, earthquakes and droughts are just some of the natural disasters. While Trinidad and Tobago and The Bahamas have made great strides in overcoming long-lasting economic devastation in the region, Haiti and Jamaica are overwhelmed by poverty still. Environmental factors certainly assist in the obstacles to overcome poverty, yet they alone are not the cause. Economies must develop to withstand natural disasters through preparation; one of those ways is by creating emergency funds. Mutually beneficial relationships with other countries are also necessary to ensure contributable funds in isolated disasters. These are also some beginning steps for the individual seeking financial freedom and security; savings is one of the most important, and friends with likeminded financial principles another. History also plays a major role in the development of relationships; is not only ensures swift response to help align countries, but also creates partnership in mercantilism. The lack of morale and economic integrity of a nation plays a role in the causes of poverty, resulting in a loss of respect among other nations-- affecting the desire for trade and cooperation. -

Jamaica Info Packet.Pdf

Flights Very tentative – TBD based on number of participants. If you would like to use miles to book flights, this can be arranged with Leah. Depart Thursday, February 11, 2016 at 11:20pm from JFK on Jet Blue #659 (non-stop), Arrive in Kingston at 4:30am (next day) Return Monday, February 15, 2016 at 2:55pm on Jet Blue #60, arrive at JFK at 6:45pm Hotel Knutsford Court Hotel (16 Chelsea Avenue, Kingston 5, Jamaica) ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Student code of conduct will be signed by parents and all participants. If any of the code is violated teens will be put on a direct flight back to NY immediately at the expense of their parents. Further consequences and participation in JCC Teen Action Committee program will be evaluated on return and on a per person basis. There will be NO ALCOHOL, NO DRUGS and NO CIGARETTES on this trip for any teen or adult participants or chaperones. Chaperones - Leah Schechter and an additional adult will accompany the minimum 8 participants. After that, chaperones will be at a 1:5 ratio. Parents interested in participating as a chaperone should speak to Leah. Deposit is non-refundable as of November 15th. Full payment is due prior to departure in February 2016. It is recommended that all participants purchase their own travel insurance. Following return of the travel experience all participants will receive formal letter of participation for over 36 hours of community service. Commitments between now and the trip All participants will be required to participate in two conference calls and one in person group meeting prior to departure. -

Jamaican Seismology with Reference to Other Islands in the Greater Antilles Margaret D

Jamaican Seismology with reference to other islands in the Greater Antilles Margaret D. Wiggins-Grandison Earthquake Unit University of the West Indies- Mona Jamaica December 5-6, 2005 MDWG-ISE/CD Contents Historical earthquakes Tectonic setting Recent significant earthquakes Current seismicity Research and development Future outlook December 5-6, 2005 MDWG-ISE/CD The Earthquake Unit • operate the Jamaica Seismograph Network (JSN) [12 stations, 8 accelerographs] • maintain a database of all earthquakes recorded by the JSN • inform the public about recent earthquakes • collect information about effects of earthquakes felt in Jamaica • conduct research on the seismicity, seismic hazard, site response and vibration analyses & related fields • Exchange data with international and regional networks • Jamaica’s National Data Centre of the Comprehensive (Nuclear) Test-Ban Treaty Organization’s (CTBTO) International Data Centre December• Welcome 5-6, 2005 visits from school MDWG-ISE/CD & community groups Global frequency of occurrence of earthquakes Magnitude Occurrence on Descriptor average per year ≥ 8 1 Great 7-7.9 17 Major 6-6.9 134 Strong 5-5.9 1,319 Moderate 4-4.9 Est. 13,000 Light 3-3.9 Est. 130,000 Minor 2-2.9 Est. 1,300,000 Very minor December 5-6, 2005 MDWG-ISE/CD Historical Earthquakes Eastern Jamaica Western Jamaica • 1692 (X) • 1839 (VII) • 1771 (VII) • 1943 (VII) • 1812 (VIII) • 1957 (VIII) • 1907 (IX) • 1914 (VII) • 1993 (VII) December 5-6, 2005 MDWG-ISE/CD 1692 Port Royal, Jamaica December 5-6, 2005 MDWG-ISE/CD 1946 DR earthquake -

Country Information and Guidance Jamaica: Fear of Organised Criminal Gangs

Country Information and Guidance Jamaica: Fear of organised criminal gangs Version 1.0 July 2015 Preface This document provides guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling claims from – as well as country of origin information (COI) about – persons fearing organised criminal gangs in Jamaica. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the guidance and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please e-mail us. -

The Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America

The Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America VOL. X JUNE, 1920 No. 2 JAMAICA EARTHQUAKES AND THE BARTLETT TROUGH By STEPHEN TABER INTRODUCTION The island of Jamaica lies between the parallels 17 ° 42' and 18 ° 32' north and the meridians 76 ° 11' and 78 ° 23' west. Its extreme length in an east-west direction is 232 kilometers and its greatest width north and south is 79 kilometers; the total area being 10,900 square kilometers. Within this relatively small area many earth- quakes have been felt since the discovery and settlement of the island over four centuries ago. Although most of the earthquakes have been of low intensity, several have resulted in destruction of property, and the earthquake of 1692 must be classed among the great earthquakes of history. The earthquake of 1907 was extremely destructive but did not equal that of 1692 in intensity. It is impossible to fix the origin of the large number of shocks that have caused no appreciable damage, for in most cases the only information preserved is the date and time of their occurrence. However, fairly good descriptions of the more destructive earthquakes are available, which make it possoble to fix their origins approximately at least; and it is a general rule that most of the weak shocks of a district originate in the same locali- ties as the stronger ones. TIlE EARTHOUAKE OF 1687 The first earthquake of which we have knowledge occurred on Sunday, February 19, 1687, at about 8 a.m. Sir Hans Sloane states that it "was generally felt all over the island at the same time, or near it; some houses therein being cracked and very near ruined, others being uncovered of their tiles; very few escaped some injury.