The Jamaican Crime Problem: Peace Building and Community Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamaica-Wikipedia-Re

4/15/2017 Jamaica Wikipedia Coordinates: 18°N 77°W Jamaica From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia i Jamaica ( /dʒәˈmeɪkә/) is an island country situated in the Jamaica Caribbean Sea, consisting of the thirdlargest island of the Greater Antilles. The island, 10,990 square kilometres (4,240 sq mi) in area, lies about 145 kilometres (90 mi) south of Cuba, and 191 kilometres (119 mi) west of Hispaniola (the island containing the nationstates of Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Jamaica is the fourthlargest island country in the Caribbean, by area.[6] Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Out of Many, One People" Inhabited by the indigenous Arawak and Taíno peoples, the island came under Spanish rule following the arrival of Anthem: Christopher Columbus in 1494. Many of the indigenous people "Jamaica, Land We Love" died of disease, and the Spanish imported African slaves as 0:00 MENU labourers. Named Santiago, the island remained a possession of Royal anthem: "God Save the Queen" Spain until 1655, when England (later Great Britain) conquered it and renamed it Jamaica. Under British colonial rule Jamaica became a leading sugar exporter, with its plantation economy highly dependent on slaves imported from Africa. The British fully emancipated all slaves in 1838, and many freedmen chose to have subsistence farms rather than to work on plantations. Beginning in the 1840s, the British imported Chinese and Indian indentured labour to work on plantations. The island achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 6 August 1962.[7] With 2.8 million people, Jamaica is the thirdmost populous Anglophone country in the Americas (after the United States and Canada), and the fourthmost populous country in the Caribbean. -

RESOLVING POVERTY in the CARIBBEAN 1 Akilah Jones

RESOLVING POVERTY IN THE CARIBBEAN 1 Akilah Jones Introduction The Caribbean Sea has a host of islands that are adjacent to the Americas; it is full of nation states more or less developed. Haiti and Jamaica are the poorest nations in the Caribbean; the wealthiest are Trinidad and Tobago, The Bahamas, and Puerto Rico. Environmental issues and natural disasters are some of the continuous battles that these nations have faced, but some have found ways to cultivate their land and rise above these issues that plague them. Hurricanes, earthquakes and droughts are just some of the natural disasters. While Trinidad and Tobago and The Bahamas have made great strides in overcoming long-lasting economic devastation in the region, Haiti and Jamaica are overwhelmed by poverty still. Environmental factors certainly assist in the obstacles to overcome poverty, yet they alone are not the cause. Economies must develop to withstand natural disasters through preparation; one of those ways is by creating emergency funds. Mutually beneficial relationships with other countries are also necessary to ensure contributable funds in isolated disasters. These are also some beginning steps for the individual seeking financial freedom and security; savings is one of the most important, and friends with likeminded financial principles another. History also plays a major role in the development of relationships; is not only ensures swift response to help align countries, but also creates partnership in mercantilism. The lack of morale and economic integrity of a nation plays a role in the causes of poverty, resulting in a loss of respect among other nations-- affecting the desire for trade and cooperation. -

Country Information and Guidance Jamaica: Fear of Organised Criminal Gangs

Country Information and Guidance Jamaica: Fear of organised criminal gangs Version 1.0 July 2015 Preface This document provides guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling claims from – as well as country of origin information (COI) about – persons fearing organised criminal gangs in Jamaica. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the guidance and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please e-mail us. -

The Importance of Jamaica

THE EFFECT OF DRUGS, GANGS AND FEAR OF CRIME ON ATTITUDES ABOUT DEMOCRACY AND GOVERNMENT IN JAMAICA By LUIS ALBERTO CARABALLO A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Luis Alberto Caraballo 2 To Mami and Papi 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research would not have been feasible without the help of the faculty and staff at the Center for Latin American Studies and the Latin American Collection Library at the University of Florida, who provided so many of the necessary resources over my course of study. I would like to thank Dr. Ron Akers and Dr. Tim Clark who provided some much needed early assistance towards completing my project. Finally and most importantly, I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Leann Brown and Dr. Charles Wood, whose patience and encouragement was of monumental importance in both finishing this thesis and completing the master’s program. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................ 6 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... -

Youth Violence and Organized Crime in Jamaica

YOUTH VIOLENCE AND ORGANIZED CRIME IN JAMAICA: CAUSES AND COUNTER-MEASURES An Examination of the Linkages and Disconnections Final Technical Report AUTHORED BY HORACE LEVY October 2012 YOUTH VIOLENCE AND ORGANIZED CRIME IN JAMAICA: CAUSES AND COUNTER-MEASURES An Examination of the Linkages and Disconnections Final Technical Report AUTHORED BY HORACE LEVY October 2012 Name of Research Institution: The University of the West Indies (UWI) – Institute of Criminal Justice and Security (ICJS) International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Grant Number: 106290-001 Country: Jamaica Research Team: – Elizabeth Ward (Principal Investigator) – Horace Levy (Consultant – PLA Specialist) – Damian Hutchinson (Research Assistant) – Tarik Weekes (Research Assistant) Community Facilitators: – Andrew Geohagen (co-lead) – Milton Tomlinson (co-lead) – Vernon Hunter – Venisha Lewis – Natalie McDonald – Ricardo Spence – Kirk Thomas – Michael Walker Administrative Staff: – Deanna Ashley (Project Manager) – Julian Moore (Research Assistant) – Andrienne Williams Gayle (Administrative Assistant) Author of Report: Horace Levy Date of Presentation to IDRC: October 2012 This publication was carried out with the support of a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada. The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of IDRC. CONTENTS Acknowledgements 5 Synthesis 6 Background and Research Problem 8 Objectives 10 Methodology and Activities (Project Design & Implementation) 12 Project Outputs and Dissemination 22 Project Outcomes 24 A. Research Findings 24 1. Crews and Gangs Distinguished 24 2. Case of Defence Crew becoming Criminal Gang 29 3. Violence of Individuals 30 4. Influence of the Shower Posse 31 5. The Tivoli Gardens Incursion and Central Authority 32 6. Leadership 34 7. Gang Members and Legal Alternatives 34 8. Women 34 9. -

(“Wi Deal Wid It Wiself”): a Look at Life in the Jamaican Garrison by Marsha-Ann Tremaine Scott B.Sc., University of the West Indies, 2007

We Deal With It Ourselves (“Wi Deal Wid it Wiself”): A Look at Life in the Jamaican Garrison by Marsha-Ann Tremaine Scott B.Sc., University of the West Indies, 2007 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Criminology Faculty of Arts & Social and Sciences © Marsha-Ann Tremaine Scott 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2014 Approval Name: Marsha-Ann T. Scott Degree: Master of Arts (Criminology) Title of Thesis: We Deal With It Ourselves (“Wi Deal Wid it Wiself”): A Look at Life in the Jamaican Garrison Examining Committee: Chair: Bill Glackman, Ph.D. Associate Professor Brian Burtch, Ph.D. Senior Supervisor Professor Sheri Fabian, Ph.D. Supervisor Senior Lecturer Marlyn Jones, Ph.D. External Examiner Professor Division of Criminal Justice California State University Date Defended/Approved: March 21, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement iv Abstract Created by the Jamaican political administration to garner support from the marginalized and socially excluded groupings in the inner city, the garrison has morphed into a counter society that subverts all forms of legitimate authority. Protected and led by dons who were originally appointed to carry out the dictates of the politicians, these men now possess full control of the garrison and have an unswerving allegiance from the members of these communities. The provision of opportunities for skills training, jobs, and education for members of these areas could possibly remove the state of dependency and ultimately the power that those possessing an abundance of wealth wield. The study includes semi-structured interviews with ten (10) participants from the community of August Town, Jamaica who provided insight into life in the garrison. -

National Security Policy for Jamaica

i TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................................iii A Vision for National Security for Jamaica ....................................................................................viii CHAPTER ONE: – STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS..............................................1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................1 Setting the context..............................................................................................................................2 The impact of international geo-politics ............................................................................................3 The global economy ...........................................................................................................................3 Transnational & organised crime .......................................................................................................4 Domestic political maturity and human, social and economic development .....................................5 Global environmental hazards and disasters ......................................................................................5 Summary of Jamaica’s security concerns ..........................................................................................6 CHAPTER TWO: – THREATS TO JAMAICA’S NATIONAL SECURITY .................................8 -

Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Jamaica

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II.144 Doc. 12 10 August 2012 Original: English REPORT ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN JAMAICA 2012 Internet: http://www.cidh.org OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. Report on the situation of human rights in Jamaica = Informe sobre la situación de los derechos humanos en Jamaica. v. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5887‐3 Human rights‐‐Jamaica. 2. Civil rights‐‐Jamaica. I. Title. II. Title: Informe sobre la situación de los derechos humanos en Jamaica. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.144 Doc.12 Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on August 10, 2012 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS José de Jesús Orozco Henríquez Tracy Robinson Felipe González Dinah Shelton Rodrigo Escobar Gil Rosa María Ortiz Rose‐Marie Belle Antoine ****** Assistant Executive Secretary: Elizabeth Abi‐Mershed REPORT ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN JAMAICA TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................1 A. Scope and legal framework of the report....................................................1 B. The IACHR visit .............................................................................................2 C. Draft report and response by the Jamaican State .......................................4 CHAPTER II CITIZEN SECURITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS .............................................................5 -

V5. Wint-Dissertation

Copyright by Traci-Ann Simone Patrice Wint 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Traci-Ann Simone Patrice Wint Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: After Paradise: Jamaican Tourism and Nationalism in the Wake of Colonialism Committee: Edmund T. Gordon, Supervisor Lyndon Gill Deborah Thomas Lisa Thompson João Vargas After Paradise: Jamaican Tourism and Nationalism in the Wake of Colonialism by Traci-Ann Simone Patrice Wint Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2019 Dedication To Naima and Zora. My music and my poetry. My inspiration and my reason. Acknowledgements One, one cocoa full basket, every mickle mek a muckle, and I could not have done this alone. My journey to this point has been circuitous and without the support of a large community of friends, family, scholars, and mentors I would not have made it through what at many times felt like a Sisyphean task. I am grateful that this work benefitted from a committee of scholars generous with their time and their knowledge, who supported me not only as a scholar but as a whole person. My advisor Edmund T. Gordon has made it clear time and time again that he does not like long introductions or awkward displays of praise, but he and I have been on this road too long for me to let his humility stop me, so even though I know this will probably make him cringe, I have to say thank you. -

Crime, Violence and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options In

Report No. 37820 Crime, Violence, and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options in the Caribbean March 2007 A Joint Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Latin America and the Caribbean Region of the World Bank ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution CEM Country Economic Memorandum CFATF Caribbean Financial Action Task Force CGNAA COSAT Guard for the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba CONANI Consejo Nacional de la Niñez CPI Corruption Perceptions Index CPTED Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design CTS Crime Trends Surveys – United Nations DALYs Disability-Adjusted Life Years DHS Department of Homeland Security EBA Educación Básica para Adultos y Jóvenes ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean ENHOGAR Encuesta Nacional de Hogares de Propósitos Múltiples EU/LAC European Union/Latin American and the Caribbean FARC Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia GDP Gross Domestic Product ICS Investment Climate Survey ICVS International Crime Victims Survey LAC Latin America and Caribbean OECS Organization of Eastern Caribbean States PATH Program for Appropriate Technology in Health RNN Royal Navy of the Netherlands RSS Regional Security System RTFCS Regional Task Force on Crime and Security UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime WDR World Development Report WHO World Health Organization Vice President: Pamela Cox Country Director: Caroline Anstey PREM Director: Ernesto May Sector Manager: Jaime Saavedra Chanduvi Lead Economist: Antonella Bassani Task Managers: -

The Influence of Violent Crimes on Health in Jamaica: a Spurious Correlation Policy Section

DOI: JCDR/2012/3179:1860.1 Original Article The Influence of Violent Crimes on anagement & M Health in Jamaica: A Spurious Correlation Policy Section Health and an Alternative Paradigm PAUL A. BOURNE, COLLIN PINNOCK, DAMION K. BLAKE ABSTRACT Methods: By using 21 years of data which were collected Background: The discourse on crime and health in Jamaica is from different publications of the government departments in devoid of the influence of violent crimes on the nature of the Jamaica, this study utilized different econometric techniques to health. The discourse on health recognizes that violent crime carry out the data analyses. is a cause of mortality; however, health researchers have paid Findings: On seeking to reduce the specification errors, this limited attention to this area, despite the fact that annually work found that there existed no real relationship between violent murders have taken more lives than HIV/AIDS. crime and the illness rate, and that the illness rate was a function Objectives: The objectives of this study were to test the of 1) health care utilization, 2) unemployment and 3) GDP. hypotheses that 1) violent crime directly influenced the health Conclusion: The positive correlation between GDP and the status, 2) the correlation between violent crime and health was illness rate in Jamaica suggested that health policies should a spurious one, 3) other selected macroeconomic variables be planned differently in the periods of growth as against the influenced the health status of Jamaica, 4) explained the model economic downturn. illness rate 5) established a number of violent crime equations, and 6) explained the cyclical distribution of the illness rates. -

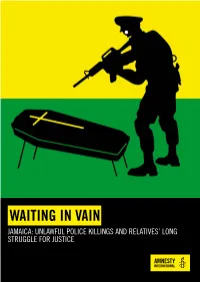

Waiting in Vain

WAITING IN VAIN JAMAICA: UNLAWFUL POLICE KILLINGS AND RELATIVES’ LONG STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover: Art produced by Argentinean graphic artist, Dr. Alderete, for Amnesty International, Mexico 2016. Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. @Amnesty International / Dr. Alderete https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AMR 38/5092/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 Key recommendations 6 Methodology 7 Obstacles to Amnesty International’s research 8 Acknowledgements 8 Terminology 8 2. A DECADES-OLD EPIDEMIC OF VIOLENCE 9 Challenging impunity 13 3. HOW THE POLICE KILL 15 The impact on women of police operations 15 Killing criminal suspects 17 “Killa police” 18 Mistaken identities 20 Planned operations 22 Tampering with the crime scene 22 Letting victims “bleed out” 24 Stray bullets 25 Deaths in custody 25 Standards on use of force 26 WAITING IN VAIN 3 Jamaica: unlawful police killings and relatives’ long struggle for justice AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL 4.