Stanislav Grof, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth in Buddhism

Piya Tan SD 36.1 Myth in Buddhism Myth in Buddhism 1 Symbols and stories in our actions and the potential for good An essay by Piya Tan ©2007, 2011 Dedicated to Patrick Ong, Singapore, who loves mythology and the divine. 1 The myths we live by 1.0 DEFINITIONS 1.0.1 Theories of Buddhist myth 1.0.1.1 A myth is a story that is bigger than we are, lasts longer than we do, and reflects what lies deep in our minds and hearts, our desires, dislikes and delusions.1 When a story grows big enough, be- yond the limits of everyday imagination and language, it becomes a myth. To recognize and understand myths is to raise our unconscious2 into the realm of narrative and our senses, so that we are propelled into a clear mindfulness of what we really (the truth) and what we can be (the beauty). Such a vision of truth and beauty inspire us to evolve into true individuals and wholesome communities.3 1.0.1.2 A myth breaks down the walls of language, with which we construct our worlds of sights, sounds, smells, tastes and touches. Next, we begin to identify with these creations like a creator-God priding over his fiats. Then, we delude ourselves that we have the right to dominate others, other nations, and nature herself. Since we have deemed ourselves superior to others, we surmise that we have the right to command and rule others, to be served and indulged by them. This is the beginning of slavery and colonialism. -

Samprayoga Concept in the Text of Paururava Manasija Sutra

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A SAMPRAYOGA CONCEPT IN THE TEXT OF PAURURAVA MANASIJA SUTRA I GedeSuwantana* I GustiNgurahPertuAgung ** Abstract: ‘PaururavaManasija Sutra’ is one of the kama's texts that talks about sexual pleasure and all related to it. The unique thing in this text is to use religious-spiritual terms in its descriptions. One of the interesting terms becomes the subject of this study is the word 'samprayoga' which refers to the meaning of 'achieving pleasure from sexual intercourse'. In yoga literature, the word 'samprayoga' has the meaning of 'union' and the like in the spiritual context. The reason why the term is used in this study due to theterm is the chosen focus that fulfil this study. The concept of ‘samprayoga’ in the ‘PurauravaManasija Sutra’ text that describes sexual pleasure will be read through the view of yoga and tantra. The literature of tantra, for example, once stated that sex acts will become only divine when it is able to be transcended. Sex action is the medium to achieve the highest awareness. ‘Shiva’ and ‘Sakti’ are the cosmic principles that underlie this teaching. In the physical context, energy flows through sex, and in a spiritual context, the energy flows toward the highest source of all existences. -

Haṭha Yoga – in History and Practice

Haṭha yoga – in history and practice. Haṭha yoga as tantric yoga Haṭha yoga – in history and practice. Haṭha yoga as tantric yoga Gitte Poulsen Faculty Humaniora och samhällsvetenskap. Subject Points 30 ECTS Supervisor Kerstin von Brömssen Examiner Sören Dalevi Date 1/10-2014 Serial number Abstract: The study investigates the field of haṭha yoga as it is described in the medieval Haṭhayogapradīpikā, a work on yoga composed in Sanskrit from the Nāth tradition. The study have then compared these practices, practitioners and the attitudes towards them, with interviews conducted in modern Varanasi, India. The focus in the assignment is the connection between haṭha yoga and tantric practices since tantra has been crucial in the forming of the early haṭha yoga and classical haṭha yoga, but slowly has been removed through different reformations such as under the Kashmir Śaivism. The tantric practices, especially those associated with left hand tantra, became less progressive and were slowly absorbed in mainstream Hinduism under several reformations during the 9th-15th century. Ideas about topics like austerities and alchemy were more and more replaced by conceptions of the subtle body and kuṇḍalinī and the practices became more symbolized and viewed as happening inside the practitioner’s body. Tantra was important in the framework of haṭha yoga but the philosophy and practitioners of haṭha yoga has like tantra been absorbed and mixed into different philosophies and forms of yoga practice. The practitioners has gone from alchemists, ascetics and left hand tantrics to be absorbed into the wider community which is evident in modern Varanasi. None of the haṭha yoga practitioners interviewed were Nāths, ascetics or alchemists and combined their haṭha practice with not only tantric philosophy but many different philosophies from India. -

Cosmic Riddles!

Cosmic Riddles! COSMIC RIDDLES BY Kavi Yogi Mahrshi Dr Shuddhananda Bharathi Published BY Shuddhananda Library, Thiruvanmiyur, Chennai 600 041. Ph: 97911 77741 Copy Right : @Shuddhananda Yoga Samaj(Regd), Shuddhananda Nagar, Sivaganga - 630 551 Cosmic Riddles! 1. RIDDLES, RIDDLES !! Riddles, riddles everywhere, in and out, up and down, right and left! Humanity is confronted with problems--domestic, social, economic, cultural, religious! We live in a changing world-thoughts change, modes change, and deeds change, leaders change, governments change and times change out of recognition. But something, some inner urge seeks for a lasting peace bliss and power. The central Truth coos ‘I’m Aum with every heart beat. But we do not know how to open the inner door and reach it. It is the living sym- phony of existence!. Behold a watch: A living hand turns the key and it runs tickticking. The watch goes on saying’O man, watch your word, act, thought, character and heart’. Even so a mystic destiny has given force to this throbbing heart which pumps up blood to the brain and feeds the nerves and runs the human mecha- nism. To rediscover this I-am-ness within is the way to solve the riddle of exist- ence. A gentleman had a faithful servant. He went one day on a pilgrimage with all the members of his family ordering the servant to take care of the door. The faithful servant was earnestly looking at the door all day long. He got sleepy. So he took the door home and spread his bed upon it and dozed. -

Lord Shree Jagannath - a Great Assimilator of Tantric Impressions for Human Civilization

Orissa Review Lord Shree Jagannath - a Great Assimilator of Tantric Impressions for Human Civilization Rajendra Kumar Mohanty Dynamics of social changes find expression, sensitivity to the beautiful and abiding besides other channels, through religious institution equanimity and the calm joy of the spirit which as religious beliefs and dictums cover the major characterise the sages and many of the part of our community life. humblest people in the Orient.” Language and literature are the vehicles Indian literature possesses what is best and mirrors of those in the world of human changes. Hence, language knowledge and wisdom. A and religious institutions, close relationship between both of which contain values religion and culture is for changing social systems, undeniable. Religion is have inseparable link. India ultimately a code of ethics possesses many languages based on spiritualism. and literatures, but Indian Religious beliefs, ideas and literature is one, though concepts are, in reality, written in many languages. projections of human value Indian literature systems. Religious life is an consisting of its Vedas, expression of the collective Upanishads, Ramayan, values and life of a social Mahabharat in ancient group (Emile Durkhem period has always observed). Shri Jagannath demonstrated that, “It Dharma or Shri Jagannath should eventually be Cult and its offsoot possible to achieve a Jagannath culture propagate society for mankind some specific human values. generally in which the higher standard of living What is generally called the Jagannath cult of the most scientifically advanced and is not in the narrow and limited sense of a school theoretically guided western notions is of thought or a system of rituals or liturgies. -

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism James G. Lochtefeld, Ph.D. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. New York Published in 2001 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © 2001 by James G. Lochtefeld First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lochtefeld, James G., 1957– The illustrated encyclopedia of Hinduism/James G. Lochtefeld. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1 (set) ISBN 0-8239-3180-3 (volume 2) 1. Hinduism Encyclopedias. I. Title BL1105.L63 2000 294.5'03—dc21 99-27747 CIP Manufactured in the United States of America Nachiketas poetry are dedicated to Krishna, a dif- ferent form of Vishnu. This seeming divergence may reflect her conviction that all manifestations of Vishnu are ultimately the same or indicate the dif- N ference between personal devotion and literary expression. The thirty poems in the Nacciyar Tirumoli are told by a group of unmar- ried girls, who have taken a vow to bathe Nabhadas in the river at dawn during the coldest (c. 1600) Author of the Bhaktamal month of the year. This vow has a long (“Garland of Devotees”). In this hagio- history in southern India, where young graphic text, he gives short (six line) girls would take the oath to gain a good accounts of the lives of more than two husband and a happy married life. -

Tantricism in the Cult of Lord Jagannath

Orissa Review June - 2009 Tantricism in the Cult of Lord Jagannath Dr. Sidhartha Kanungo The cult of Jagannath is not a sectarian religion, Yantras play an important role in tantricism. but a cosmopolitan and eclectic philosophy. In Various Yantras have been engraved on the course of time, the cult of Jagannath took an Ratnasimhasan on which Lord Jagannath, Lord Aryanised form and various major faiths like Balbhadra and Devi Subhadra are worshipped. Saivism, Saktism, Vaishnavism, Tantricism, In the daily worship of Lord and also at the time Jainism and Buddhism have of Darupratistha (installation been assimilated into this cult. of new image), representation Whatever may be the origin of Sri Yantra, Bhubaneswari, of this cult, it has been Yantra and various Mandalas admitted both by the scholars are also noticed. Jagannath is belonging to different worshipped as Krushna- religious traditions and faiths Basudev. But due to the that this culture is centre influence of Tantricism, around which in course of Jagannath is perceived as time divergent currents and 'Dakshin Kali', Balabhadra as cross currents have revoked. 'Jyotirmayeem Tara' and Devi However, this paper Subhadra as 'Adyasakti makes an attempt to analyse Bhubaneswari'. the influence of Trantricism on It is known from the cult of Lord Jagannath. different tantric texts that Tantricism in a number of ways influences Orissa as well as Puri, which Jagannath cult. Jagannath is worshipped as God is otherwise known as 'Srikshetra', is a great of Tantra. We notice various Nyasas such as tantric pitha or place. After the death of Sati in Sadanga-nyasa, Kasbadi-nyasa, Matrkanyasa, 'Dakshya Yanga'. -

Mahanirvana Tantra

Mahanirvana Tantra Tantra of the Great Liberation Translated by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe) Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE Indian Tantras, which are numerous, constitute the Scripture (Shastra) of the Kaliyuga, and as such are the voluminous source of present and practical orthodox "Hinduism." The Tantra Shastra is, in fact, and whatever be its historical origin, a development of the Vaidika Karmakanda, promulgated to meet the needs of that age. Shiva says: "For the benefit of men of the Kali age, men bereft of energy and dependent for existence on the food they eat, the Kaula doctrine, O auspicious one! is given" (Chap. IX., verse 12). To the Tantra we must therefore look if we would understand aright both ritual, yoga, and sadhana of all kinds, as also the general principles of which these practices are but the objective expression. Yet of all the forms of Hindu Shastra, the Tantra is that which is least known and understood, a circumstance in part due to the difficulties of its subject-matter and to the fact that the key to much of its terminology and method rest with the initiate. The present translation is, in fact, the first published in Europe of any Indian Tantra. An inaccurate version rendered in imperfect English was published in Calcutta by a Bengali editor some twelve years ago, preceded by an Introduction which displayed insufficient knowledge in respect of what it somewhat quaintly described as "the mystical and superficially technical passages" of this Tantra. A desire to attempt to do it greater justice has in part prompted its selection as the first for publication. -

Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls : Popular Goddess

Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal JUNE McDANIEL OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls This page intentionally left blank Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal june mcdaniel 1 2004 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Sa˜o Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright ᭧ 2004 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McDaniel, June. Offering flowers, feeding skulls : popular goddess worship in West Bengal / June McDaniel. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-19-516790-2; ISBN 0-19-516791-0 (pbk.) 1. Kali (Hindu deity)—Cult—India—West Bengal. 2. Shaktism—India—West Bengal. 3. West Bengal (India)— Religious life and customs. I. Title. BL1225.K33 W36 2003 294.5'514'095414—dc21 2003009828 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Acknowledgments Thanks go to the Fulbright Program and its representatives, whose Senior Scholar Research Fellowship made it possible for me to do this research in West Bengal, and to the College of Charleston, who granted me a year’s leave for field research. -

JPM QUARTERLY Jan - Mar ’19 the Participants Watching the Screening of ‘Looks of a Lot’ Table of Contents Director’S Note

JPM QUARTERLY Jan - Mar ’19 The participants watching the screening of ‘Looks of a Lot’ Table Of Contents Director’s Note ................................................................. Page 01 Aesthetics ........................................................................ Page 03 Indian Aesthetics ............................................................. Page 04 Forthcoming Programmes in Indian Aesthetics ................ Page 10 Islamic Aesthetics ............................................................ Page 11 Forthcoming Programme in Islamic Aesthetics ............. Page 15 Yoga and Tantra ................................................................ Page 19 Buddhist Aesthetics ......................................................... Page 24 Forthcoming Programmes in Buddhist Aesthetics ........... Page 27 Criticism and Theory ......................................................... Page 29 Critical Theory, Aesthetics, and Practice ......................... Page 30 Forthcoming Programmes in Criticism and Theory ........... Page 37 Theoretical Foundations .................................................... Page 38 Forthcoming Programmes in Theoretical Foundations ..... Page 40 Community Engagement ................................................. Page 41 Forthcoming Programmes in Community Engagement .. Page 46 Creative Processes ......................................................... Page 47 Curatorial Processes ....................................................... Page 48 JPM Supporters ................................................................ -

Svoboda-Aghora-2-Text.Pdf

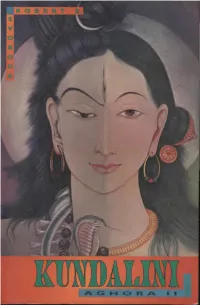

AGHORA 11= — IN THE SERIES — AGHORA, At the Left Hand of God, Robert E. Svoboda AGHORA II: Kundalini, Robert E. Svoboda Kundalini Forthcoming: AGHORA III: The Law of Karma, Robert E. Svoboda 6 Robert E. Svoboda Foreword by Robert Masters, Ph.D. Illustrations, Captions and Appendix by Robert Beer Brotherhood of Life Publishing Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA ©1993 Robert E. Svoboda Illustrations, Motifs, Captions (St Appendix: with Thanks to and ©1993 Robert Beer First Printed 1993, Reprinted 1995 Published by Brotherhood of Life, Inc. 110 Dartmouth, SE Albuquerque, NM 87106-2218 www.brotherhoodoflife.com ISBN 0-914732-3 1-5 Co-published 1998 with She, the Eternal One, is the Supreme Knowledge, the cause of freedom from Sadhana Publications C) delusion and the cause of the bondage of manifestation. 1840 Iron Street, Suite C She indeed is sovereign over all sovereigns. Bellingham, WA 98225 (Devi Mahatmya, 1.57-58) ISBN 0-9656208-2-4 Dedicated to the Great Goddess, the Divine Mother of the Universe. All rights reserved. No part of this publication including illustrations may be the Kundalini Shakti. reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information or retrieval system, including the Internet, without permission in writing from Brotherhood of Life, Inc. or Sadhana Publications. Reviewers may quote brief passages. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FOREWORD .13 INTRODUCTION.17 Chapter 1: AGNI.29 Chapter 2: KUNDALINI.51 Self-Identification.59 Coverings .62 Nadis and Chakras.64 The Nine Chakras.67 Raising Kundalini.72 Samadhi.76 Kula Kundalini.77 The Snake.82 The Chakras.83 Kula Kundalini.84 Chapter 3: PRELIMINARIES .87 Food.92 Panchamakara.95 Chapter 4: SADHANA.113 Khanda Manda Yoga.113 Name and Form. -

Tantra, Shakti, and the Secret Way Julius Evola

RELIGION / PHILOSOPHY $16.95 THE YOGA OF POWER ranslated into English for the first time, this book will come Tas a surprise to those who think of India as a civilization characterized only by contemplation and the quest for nirvana. The author introduces two Hindu movements - Tantrism and Shaktism - both of which emphasize a path of action as well as mastery over secret energies latent in the body. Tracing the influence of these movements on the Hindu tradition from the fourth century onward, Evola focuses on the perilous practices of the Tantric school known as Vamachara - the "Way of the Left Hand" - which uses human passions and the power of Nature to conquer the world of the senses. During the current cycle of dissolution and decadence, known in India as Kali Yuga, the spiritual aspirant can no longer dismiss the physical world as mere illusion but must grapple with - and ultimately transform - the powerful and often destructive forces with which we live. Evola draws from original texts to describe methods of self-mastery, including the awakening of the serpent power, initiatory sexual magic, and evoking the mantras of power. Author of Eros and the Mysteries of Love, Julius Evola (1898- 1974) was a controversial renegade scholar, philosopher, and social thinker. He has long been regarded as a master of European esotericism and occultism as well as a leading authority on Tantra and magic. INNER TRADITIONS ONE PARK STREET ROCHESTER, VERMONT 05767 Cover design by Nora Wertz THE YOGA OF POWER TANTRA, SHAKTI, AND THE SECRET WAY JULIUS EVOLA Translated by Guido Stucco Inner Traditions International Rochester, Vermont Inner Traditions International One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 First published in Italian under the title Lo Yoga Delia Potenza: Saggio sui Tantra by Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome, 1968 First U.S.