An Archaeological Survey of Ntsweng in Molepolole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance of Goats and Sheep Under Communal Grazing in Botswana Using Various Growth Measures

B07 Performance of goats and sheep under communal grazing in Botswana using various growth measures L. Baleseng, O. E Kgosikoma, A. Makgekgenene | Department of Agricultural Research, Private | Gaborone | Botswana M. Coleman, P. Morley | Institute for Rural Futures, School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences, University of New England | Armidale | Australia D. Baker, O. | UNE Business School, University of New England | Armidale | Australia S. Bahta | International Livestock Research Institute | Nairobi | Kenya DOI: 10.1481/icasVII.2016.b07 ABSTRACT We conducted a survey to evaluate the growth of goats and sheep under communal grazing, and to determine the relationship between weight, heart girth, shoulder height, and body condition score in Kweneng, Central and Kgalagadi districts, Botswana. The same animals were measured on two separate occasions, approximately one month apart, to allow growth rates to be recorded. Significant differences in growth rates between the three case study districts were found for both goats and sheep. Amongst the goats measured, gains in height and weight were significantly greater in the Kweneng district, while gains in heart girth measurement were greatest in the Central district. In the case of sheep, weight gain was significantly higher in the Central and Kgalagadi districts, increases in girth measurement were significantly higher in the Central district, and shoulder height gain was significantly greater in the Kweneng district. Statistical tests were used to determine the relationships between animal weight and the other measures taken for goats and sheep. Heart girth in both goats and sheep was shown to be a significant predictor of weight across all three districts. Likewise, shoulder height proved to be a statistically significant predictor of animal weight for both goats and sheep, across each district. -

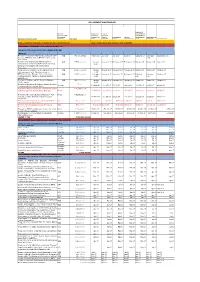

Submission Of

PROCUREMENT PLAN TEMPLATE Submission of Method of Submission of Issuing of Evaluation Reports Procurement (ICB, Documets to Invitation to to PPADB/MTC for NCB, selective, PPADB/MTC for Tender by Closing Date for Evaluation Adjudication and Award Decision by Description of Procurement activity QPP,Direct) Cost Estimate Vetting PPADB/MTC Tenders Completion by PE Award PPADB?MTC Contracts Signatire NAME OF MINISTRY: MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS NAME OF PERSONS(S) RESPONSIBLE FOR PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Category of Procurement (services/Supplies/Works) SERVICES Provision of Hardware Maintenance Services for IBM NCB P 6,070,179.26 March 2017 June 2017 July 2017 July 2017 August 2017 September September 2017 P-Series, IBM Blade Center, IBM 6400 printers and 2017 IBM Storage Provision of Unix/Linux and Windows System NCB P 5,500,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 May 2017 Administration Services for IBM P-Series and Linux 2017 Services in the Department of Information Technology Procurement of Hardware for the replacement of NCB P 12,000,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 March 2017 x86 environment with Migrations Services. 2017 IBM Tivoli Storage Manager Licenses Renewal NCB P 1,500,000.00 December January 2017 January 2017 February 2017 February February March 2017 (Licenses used for backup of business systems 2016 2017 2017 applications) Renewal of VMWare and Site Recovery Manager NCB P 5,000,000.00 January January 2017 February 2017 February 2017 March 2017 March 2017 March 2017 (SRM) Licenses 2017 Selectionof the Microsoft Software Advisor (Selection P 0.00 Selective 17/11/2016 01/01/2017 27/1/2017 02/10/2017 02/12/2017 16/2/2017 28/2/2017 of License Solution Provider (LSP)) Provision of Microsoft products - Desktop and Server P 45,699,130.69 (Enterprise Enrollment and Server & Cloud). -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

Bank of Botswana

PAPER 4 BANK OF BOTSWANA DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2009 PREPARED AND DISTRIBUTED BY THE BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT BANK OF BOTSWANA Foreword This directory is compiled and distributed by the Banking Supervision Department of the Bank of Botswana. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this directory, such information is subject to frequent revision, and thus the Bank accepts no responsibility for the continuing accuracy of the information. Interested parties are advised to contact the respective financial institutions directly for any information they require. This directory excludes Collective Investment Undertakings and International Financial Services Centre non-bank entities, whose regulation and supervision have been transferred to the Non-Bank Financial Institutions Regulatory Authority. Oabile Mabusa DIRECTOR BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT 1 DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CENTRAL BANK ............................................................................................................................................. 4 2. COMMERCIAL BANKS ................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 ABN AMRO BANK (B OTSWANA ) LIMITED ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2 ABN AMRO BANK (B OTSWANA ) OBU LIMITED ........................................................................................... -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Department of Road Transport and Safety Offices

DEPARTMENT OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND SAFETY OFFICES AND SERVICES MOLEPOLOLE • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 5920148 Fax: 5910620 P/Bag 52 Molepolole Next to Molepolole Police MOCHUDI • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate P/Bag 36 Mochudi Tel : 5777127 Fax : 5748542 White House GABORONE Headquarters BBS Mall Plot no 53796 Tshomarelo House (Botswana Savings Bank) 1st, 2nd &3rd Floor Corner Lekgarapa/Letswai Road •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Road safety (Public Education) Tel: 3688600/62 Fax : Fax: 3904067 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE VTS – MARUAPULA • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Vehicle Examination Tel: 3912674/2259 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst Near Roads Training & Roads Maintenance behind Maruapula Flats GABORONE II – FAIRGROUNDS • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination : Theory Tel: 3190214/3911540/3911994 Fax : P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE - OLD SUPPLIES • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Transport Permits • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 3905050 Fax :3932671 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone Plot 1221, Along Nkrumah Road, Near Botswana Power Corporation CHILDREN TRAFFIC SCHOOL •Road Safety Promotion for children only Tel: 3161851 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst RAMOTSWA •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Driver Examination (Theory & Practical -

Directory of Financial Institutions Operating in Botswana As at December 31, 2019

PAPER 4 BANK OF BOTSWANA DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2019 PREPARED AND DISTRIBUTED BY THE BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT BANK OF BOTSWANA Foreword This directory is compiled and distributed by the Banking Supervision Department of the Bank of Botswana. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this directory, such information is subject to frequent revision, and thus the Bank accepts no responsibility for the continuing accuracy of the information. Interested parties are advised to contact the respective financial institutions directly for any information they require. This directory excludes collective investment undertakings and International Financial Services Centre non-bank entities, whose regulation and supervision falls within the purview of the Non-Bank Financial Institutions Regulatory Authority. Lesedi S Senatla DIRECTOR BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT 2 DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CENTRAL BANK ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. COMMERCIAL BANKS ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 ABSA BANK BOTSWANA LIMITED ........................................................................................................... 7 2.2 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION OF BOTSWANA LIMITED .................................................................. -

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

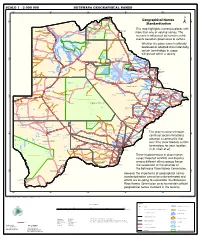

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe