Communal (1990)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

JUNE 26–30, Prague • Andrzej Kremer, Delegation of Poland, Poland List of Participants • Andrzej Relidzynski, Delegation of Poland, Poland • Angeles Gutiérrez, Delegation of Spain, Spain • Aba Dunner, Conference of European Rabbis, • Angelika Enderlein, Bundesamt für zentrale United Kingdom Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Germany • Abraham Biderman, Delegation of USA, USA • Anghel Daniel, Delegation of Romania, Romania • Adam Brown, Kaldi Foundation, USA • Ann Lewis, Delegation of USA, USA • Adrianus Van den Berg, Delegation of • Anna Janištinová, Czech Republic the Netherlands, The Netherlands • Anna Lehmann, Commission for Looted Art in • Agnes Peresztegi, Commission for Art Recovery, Europe, Germany Hungary • Anna Rubin, Delegation of USA, USA • Aharon Mor, Delegation of Israel, Israel • Anne Georgeon-Liskenne, Direction des • Achilleas Antoniades, Delegation of Cyprus, Cyprus Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères et • Aino Lepik von Wirén, Delegation of Estonia, européennes, France Estonia • Anne Rees, Delegation of United Kingdom, United • Alain Goldschläger, Delegation of Canada, Canada Kingdom • Alberto Senderey, American Jewish Joint • Anne Webber, Commission for Looted Art in Europe, Distribution Committee, Argentina United Kingdom • Aleksandar Heina, Delegation of Croatia, Croatia • Anne-Marie Revcolevschi, Delegation of France, • Aleksandar Necak, Federation of Jewish France Communities in Serbia, Serbia • Arda Scholte, Delegation of the Netherlands, The • Aleksandar Pejovic, Delegation of Monetenegro, Netherlands -

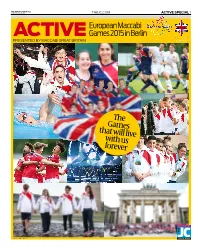

The Games That Will Live with Us Forever

THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 1 European Maccabi ACTIVE Games 2015 in Berlin PRESENTED BY MACCABI GREAT BRITAIN The Games that will live with us forever MEDIA partner PHOTOS: MARC MORRIS THE JEWISH CHRONICLE THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 2 ACTIVE SPECIAL THEJC.COM 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 3 ALL ALL WORDS PHOTOS WELCOME BY DAnnY BY MARC CARO MORRIS Maccabi movement’s ‘miracle’ in Berlin LDN Investments are proud to be associated with Maccabi GB and the success of the European Maccabi Games in Berlin. HIS SUMMER, old; athletes and their families; reuniting THE MACCABI SPIRIT place where they were banished from first night at the GB/USA Gala Dinner, “By SOMETHING hap- existing friendships and creating those Despite the obvious emotion of the participating in sport under Hitler’s winning medals we have not won. By pened which had anew. Friendships that will last a lifetime. Opening Ceremony, the European Mac- reign was a thrill and it gave me an just being here in Berlin we have won.” never occurred But there was also something dif- cabi Games 2015 was one big party, one enormous sense of pride. We will spread the word, keep the before. For the first ferent about these Games – something enormous celebration of life and of Having been there for a couple of days, torch of love, not hate, burning bright. time in history, the that no other EMG has had before it. good triumphing over evil. Many thou- my hate of Berlin turned to wonder. -

Israeli Reactions in a Soviet Moment: Reflections on the 1970 Leningrad Affair

No. 58 l September 2020 KENNAN CABLE Mark Dymshits, Sylva Zalmanson, Edward Kuznetsov & 250,000 of their supporters in New York Ciry, 1979. (Photo:Courtesy of Ilya Levkov; CC-BY-SA) Israeli Reactions in a Soviet Moment: Reflections on the 1970 Leningrad Affair By Jonathan Dekel-Chen The Kennan Institute convened a virtual meeting and public demonstrators pushed the Kremlin to retry in June 2020 marking the 50th anniversary of the the conspirators, commute death sentences for their attempted hijacking of a Soviet commercial flight from leaders, and reduce the prison terms for the rest. Leningrad.1 The 16 Jewish hijackers hoped to draw international attention to their struggle for emigration to A showing of the 2016 documentary filmOperation Israel, although many of them did not believe that they Wedding (the code name for the hijacking) produced by would arrive at their destination. Some were veterans Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, daughter of two conspirators, of the Zionist movement who had already endured preceded the Kennan panel and served as a backdrop punishment for so-called “nationalist, anti-Soviet for its conversations. The film describes the events from crimes,” whereas others were newcomers to activism.2 the vantage point of her parents. As it shows, the plight Their arrest on the Leningrad airport tarmac in June of the hijackers—in particular Edward Kuznetsov and 1970, followed by a show trial later that year, brought Sylva Zalmanson—became a rallying point for Jewish the hijackers the international attention they sought. and human rights activists in the West. Both eventually Predictably, the trial resulted in harsh prison terms. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight Against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area Rome, Italy, 29 January 2018 PROGRAMME Monday, 29 January 10.00 - 10.30 Registration of participants and welcome coffee 10.45 - 13.30 Plenary session, International Conference Hall 10.45 - 11.30 Opening remarks: - H.E. Angelino Alfano, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, OSCE Chairperson-in-Office - H.E. Ambassador Thomas Greminger, OSCE Secretary General - H. E. Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, ODIHR Director - Ronald Lauder, President, World Jewish Congress - Moshe Kantor, President, European Jewish Congress - Noemi Di Segni, President, Union of the Italian Jewish Communities 11.30 – 13.00 Interventions by Ministers 13.00 - 13.30 The Meaning of Responsibility: - Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Chairman of Yad Vashem Council - Daniel S. Mariaschin, CEO B’nai Brith - Prof. Andrea Riccardi, Founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio 13.30 - 14.15 Lunch break - 2 - 14.15 - 16.15 Panel 1, International Conference Hall “Responsibility: the role of law makers and civil servants” Moderator: Maurizio Molinari, Editor in Chief of the daily La Stampa Panel Speakers: - David Harris’s Video Message, CEO American Jewish Committee - Cristina Finch, Head of Department for Tolerance and Non- discrimination, ODHIR - Katharina von Schnurbein, Special Coordinator of EU Commission on Anti-Semitism - Franco Gabrielli, Chief of Italian Police - Ruth Dureghello, President of Rome Jewish Community - Sandro De -

1988-09-09 -Needs Redos.Pdf

*************** ********5-DIGIT 029)l 2239 li/3J/8 ft 34 7 R. I. 2Ei,JSH HIS JR I CAL ;sSSOCIATION Inside: Local News, pages 2-3 130 SESSIONS ST. Opinion, page 4 P~O~lDENCE, R'. 02906 Around Town, page 8 THE ONLY ENGL/SH--JEW!SH WEEKLY IN R./. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. VOLUME LXXV, NUMBER 41 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 1988 35¢ PER COPY The Sons of ,Jacob Synagogue is as the Baal Koreh, Torah reader, at various chassidic t<!xts. Yea riv. he the oldest "shul" in Rhode Island Mishkan Tefilah. He also would complete a tractat.e in the A New Beginning outside of the Touro Synagogue in co- published a brn,k with Rabbi Gomorah so that first-born men Newport. Conveniently located Mendel Alperin. The book. called would not have l<i fast the day of nea r downtown and the Marriott Se/er Dvash, was written to relate Passover. He a lso completed Hotel. the Sons of Jacob became the Torah insighLs of his studying all 14 volumes of the place where ,Jewish father-in-law, Rav Shabse Alperin. Maimonides Mishne Torah in one husinessmen depended on fo r a of blessed memory. year. and made a community-wide <laily minyan. Over the years, the While other men Rabbi Drazin's "siyum" lo help celebrate the Synagogu~ has hosted visitors age have retired or at least slowed Anniversary of Maimonides hirth. coming to Providence for the down. he has continued wo rking at While his future plans have yet -Jewelry Show and American Math a young man's pace. -

Snapshots of the People Behind a Young State

Snapshots of the People Behind a Young State A Unique Display in Honor of Israel's 70th Anniversary From The Bernard H. and Miriam Oster Visual Documentation Center Beit Hatfutsot, The Museum of the Jewish People Curator: Yaara Litwin | Concept & design: Neta Harel YEARS בית הספר הבינלאומי The Koret ע"ש קורת International School Ministry for Social Equality ללימודי העם היהודי for Jewish Peoplehood - 1 - Celebrating Israel: Snapshots of the People Behind a Young State A Unique Photo Display in Honor of Israel's 70th Anniversary From the collection of The Bernard H. and Miriam Oster Visual Documentation Center Beit Hatfutsot, The Museum of the Jewish People, Tel Aviv This comprehensive exhibit showcases a selection Israel, online and around the world, through innovative of historical moments that embody the great exhibits, cutting edge technology and creative endeavor that was the establishment of the State programs. of Israel, as seen through the eyes of its people. Beit Hatfutsot maintains a digital database boasting Highlighted within are the experiences of Jews from millions of items including family trees, films, and around the world who escaped hatred and fear to much more. The Database helps connect the Jewish live freely in a Jewish state. People to their roots and strengthens their personal Depicted are primarily new citizens who made and collective Jewish identity Aliyah (immigrated to Israel; literally "ascended") The Bernard H. and Miriam Oster Visual Documentation to the young country. Their struggles and triumphs Center is an unparalleled catalogue of photographs and evidence how these immigrants overcame the films documenting Jewish life, heritage and history. -

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues Dr. Jonathan Petropoulos PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, LOYOLA COLLEGE, MD UNITED STATES Art Looting during the Third Reich: An Overview with Recommendations for Further Research Plenary Session on Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues It is an honor to be here to speak to you today. In many respects it is the highpoint of the over fifteen years I have spent working on this issue of artworks looted by the Nazis. This is a vast topic, too much for any one book, or even any one person to cover. Put simply, the Nazis plundered so many objects over such a large geographical area that it requires a collaborative effort to reconstruct this history. The project of determining what was plundered and what subsequently happened to these objects must be a team effort. And in fact, this is the way the work has proceeded. Many scholars have added pieces to the puzzle, and we are just now starting to assemble a complete picture. In my work I have focused on the Nazi plundering agencies1; Lynn Nicholas and Michael Kurtz have worked on the restitution process2; Hector Feliciano concentrated on specific collections in Western Europe which were 1 Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press). Also, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming, 1999). 2 Lynn Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1994); and Michael Kurtz, Nazi Contraband: American Policy on the Return of European Cultural Treasures (New York: Garland, 1985). -

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Introduction In his poem, The Second Coming (1919), William Butler Yeats captured the moment we are now experiencing: Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. As we see the deterioration of the institutions created and fostered after the Second World War to create a climate in which peace and prosperity could flourish in Europe and beyond, it is important to understand the role played by diplomacy in securing the stability and strengthening the shared values of freedom and democracy that have marked this era for the nations of the world. It is most instructive to read the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy, in which he encouraged Americans not only to do good things for their own country, but to do good things in the world. The creation of the Peace Corps is an example of the kind of spirit that put young American volunteers into some of the poorest nations in an effort to improve the standard of living for people around the globe. We knew we were leaders; we knew that we had many political and economic and social advantages. There was an impetus to share this wealth. Generosity, not greed, was the motivation of that generation. Of course, this did not begin with Kennedy. It was preceded by the Marshall Plan, one of the only times in history that the conqueror decided to rebuild the country of the vanquished foe. -

Activities of the World Jewish Congress 1975 -1980

ACTIVITIES OF THE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS 1975 -1980 REPORT TO THE SEVENTH PLENARY ASSEMBLY OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL GENEVA 5&0. 3 \N (i) Page I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Israel and the Middle East 5 Action against Anti-Semitism. 15 Soviet Jewry. 21 Eastern Europe 28 International Tension and Peace..... 32 The Third World 35 Christian-Jewish Relations 37 Jewish Communities in Distress Iran 44 Syria 45 Ethiopia 46 WJC Action on the Arab Boycott 47 Terrorism 49 Prosecution of Nazi Criminals 52 Indemnification for Victims of Nazi Persecution 54 The WJC and the International Community United Nations 55 Human Rights 58 Racial Discrimination 62 International Humanitarian Law 64 Unesco 65 Other international activities of the WJC 68 Council of Europe.... 69 European Economic Community 72 Organization of American States 73 III. CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 75 IV. RESEARCH 83 (ii) Page V. ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS Central Organs and Global Developments Presidency 87 Executive 87 Governing Board 89 General Council.... 89 New Membership 90 Special Relationships 90 Relations with Other Organizations 91 Central Administration 92. Regional Developments North America 94 Caribbean 97 Latin America 98 Europe 100 Israel 103 South East Asia and the Far East 106 Youth 108 WJC OFFICEHOLDERS 111 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS CONSTITUENTS 113 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS OFFICES 117 I. INTRODUCTION The Seventh Plenary Assembly of the World Jewish Congress in Jerusalem, to which this Report of Activities is submitted, will take place in a climate of doubt, uncertainty, and change. At the beginning of the 80s our world is rife with deep conflicts. We are perhaps entering a most dangerous decade. -

Parshat Beshalach

Mazel Tov Yahrzeits to the Dror and Sedgh families on Mrs. Marcelle Faust - Husband the birth of Mika Rachel. Mrs. Marion Gross - Mother 2020-2021 Registration Mrs. Batya Kahane Hyman - Husband Rabbi Arthur Schneier Mrs. Rose Lefkowitz - Brother Mr. Seymour Siegel - Father Park East Day School Mr. Leonard Brumberg - Mother Early Childhood Mrs. Ginette Reich - Mother Elementary School: Grades 1-5 Mr. Harvey Drucker - Father Middle School: Grades 6-8 Mr. Jack Shnay - Mother Ask about our incentive program! Mrs. Marjorie Schein - Father Mr. Andrew Feinman - Father Mommy & Me Mrs. Hermine Gewirtz - Sister Taste of School Mrs. Iris Lipke - Mother Tuesday and Thursday Mr. Meyer Stiskin - Father 9:00 am - 10:30 am or 10:45 am - 12:15 pm Ms. Judith Deich - Mother Mr. Joseph Guttmann - Father Providing children 14-23 months with a wonderful introduction to a more formal learning environment. Through Memorial Kaddish play, music, art, movement, and in memory of Shabbat and holiday programming, children learn to love school and Ethel Kleinman prepare to separate from their beloved mother of our devoted members February 7-8, 2020 u 12-13 Shevat, 5780 parents/caregivers. Elly (Shaindy) Kleinman, Leah Zeiger and Register online at ParkEastDaySchool.org Rabbi Yisroel Kleinman. Shabbat Shira - Tu B’Shevat or email [email protected] May the family be comforted among Musical Shabbat with Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Leon & Gina Fromer the mourners of Zion & Jerusalem. Youth Enrichment Center and Cantor Maestro Yossi Schwartz Hebrew School Parshat Beshalach Pre-K (Age 4) This Shabbat is known as Shabbat Shira Parshat Beshalach Kindergarten (Age 5) because the highlight of the Torah Reading Exodus 13:17-17:16 Haftarah Elementary School (Ages 6-12) is the Song at the Sea. -

Communism's Jewish Question

Communism’s Jewish Question Europäisch-jüdische Studien Editionen European-Jewish Studies Editions Edited by the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies, Potsdam, in cooperation with the Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg Editorial Manager: Werner Treß Volume 3 Communism’s Jewish Question Jewish Issues in Communist Archives Edited and introduced by András Kovács An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-041152-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041159-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041163-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover illustration: Presidium, Israelite National Assembly on February 20-21, 1950, Budapest (pho- tographer unknown), Archive “Az Izraelita Országos Gyűlés fényképalbuma” Typesetting: