Nonhuman Animals and the Promise of the Capabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophical Ethology: on the Extents of What It Is to Be a Pig

Society & Animals 19 (2011) 83-101 brill.nl/soan Philosophical Ethology: On the Extents of What It Is to Be a Pig Jes Harfeld Aarhus University, Denmark [email protected] Abstract Answers to the question, “What is a farm animal?” often revolve around genetics, physical attri- butes, and the animals’ functions in agricultural production. The essential and defining charac- teristics of farm animals transcend these limited models, however, and require an answer that avoids reductionism and encompasses a de-atomizing point of view. Such an answer should promote recognition of animals as beings with extensive mental and social capabilities that out- line the extent of each individual animal’s existence and—at the same time—define the animals as parts of wholes that in themselves are more than the sum of their parts and have ethological as well as ethical relevance. To accomplish this, the concepts of both anthropomorphism and sociobiology will be examined, and the article will show how the possibility of understanding animals and their characteristics deeply affects both ethology and philosophy; that is, it has an important influence on our descriptive knowledge of animals, the concept of what animal wel- fare is and can be, and any normative ethics that follow such knowledge. Keywords animal ethics, animal welfare, ethology, philosophy, sociobiology Preface The historical and theoretical background for this article is an ongoing debate in the interdisciplinary fields of biology and philosophy. On the one hand, the ideas presented in this article originate in the descriptive biological sciences— for example, classic and cognitive ethology, genetic evolutionary theory, and sociobiology. -

Of Becoming and Remaining Vegetarian

Wang, Yahong (2020) Vegetarians in modern Beijing: food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/77857/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Vegetarians in modern Beijing: Food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience Yahong Wang B.A., M.A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow March 2019 1 Abstract This study investigates how self-defined vegetarians in modern Beijing construct their identity through everyday experience in the hope that it may contribute to a better understanding of the development of individuality and self-identity in Chinese society in a post-traditional order, and also contribute to understanding the development of the vegetarian movement in a non-‘Western’ context. It is perhaps the first scholarly attempt to study the vegetarian community in China that does not treat it as an Oriental phenomenon isolated from any outside influence. -

It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: the Laterial Shift to Liberation

Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: The Lateral Shift to Liberation Barry Kew rom an acute and, some will argue, a harsh, a harsh, fantastic or even tactically naive F naive perspective, this article examines examines animal liberation, vegetarianism vegetarianism and veganism in relation to a bloodless culture ideal. It suggests that the movement's repeated anomalies, denial of heritage, privileging of vegetarianism, and other concessions to bloody culture, restrict rather than liberate the full subversionary and revelatory potential of liberationist discourse, and with representation and strategy implications. ‘Only the profoundest cultural needs … initially caused adult man [sic] to continue to drink cow milk through life’.1 In The Social Construction of Nature, Klaus Eder develops a useful concept of two cultures - the bloody and the bloodless. He understands the ambivalence of modernity and the relationship to nature as resulting from the perpetuation of a precarious equilibrium between the ‘bloodless’ tradition from within Judaism and the ‘bloody’ tradition of ancient Greece. In Genesis, killing entered the world after the fall from grace and initiated a complex and hierarchically-patterned system of food taboos regulating distance between nature and culture. But, for Eder, it is in Israel that the reverse process also begins, in the taboo on killing. This ‘civilizing’ process replaces the prevalent ancient world practice of 1 Calvin. W. Schwabe, ‘Animals in the Ancient World’ in Aubrey Manning and James Serpell, (eds), Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives (Routledge, London, 1994), p.54. 1 Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 human sacrifice by animal sacrifice, this by sacrifices of the field, and these by money paid to the sacrificial priests.2 Modern society retains only a very broken connection to the Jewish tradition of the bloodless sacrifice. -

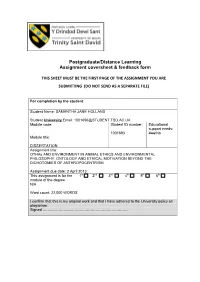

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

One Issue: Animal Liberation

One Issue: Animal Liberation We are occasionally asked why the Animal Rights Coalition is a “multi-issue” organization, instead of working solely on helping people to adopt a vegan diet. The Animal Rights Coalition mission states that ARC is “dedicated to ending the suffering, abuse, and exploitation of non-human animals through information, education, and advocacy.” One of the most important things about ARC is the consistency of our message and actions. ARC started out as, and has firmly remained, an abolitionist animal rights organization – which means that we challenge the dominant conversation that humans have about our relationships with other species. Most people view other animals as commodities for humans to use and own, and we view other animals as persons who are here for their own reasons and deserving of personal and bodily integrity. So, while some may consider us a multi-issue organization, the reality is that there is only one issue – animal liberation – and no matter what subject we’re talking about, we’re having essentially the same conversation again and again – emphasizing that animals matter in their own right, outside of what they can provide for humans, and that it is not justifiable for us to exploit or abuse them for any reason. As one facet of the conversations we have with people, we encourage them to adopt a plant-based (vegan) diet. However, we believe that veganism is about more than what one does and doesn’t eat. Veganism rejects the commodity status of animals, and with animals as commodities in more than just the food production system, we have a moral imperative to protest the use of animals in labs, circuses, the clothing industry, etc. -

Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge

1 Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge Reservation Joseph Stromberg Senior Honors Thesis Environmental Studies and Anthropology Washington University in St. Louis 2 Abstract Land is invested with tremendous historical and cultural significance for the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Widespread alienation from direct land use among tribal members also makes land a key element in exploring the roots of present-day problems—over two thirds of the reservation’s agricultural income goes to non-Natives, while the majority of households live below the poverty line. In order to understand how current patterns in land use are linked with federal policy and tribal culture, this study draws on three sources: (1) archival research on tribal history, especially in terms of territory loss, political transformation, ethnic division, economic coercion, and land use; (2) an account of contemporary problems on the reservation, with an analysis of current land policy and use pattern; and (3) primary qualitative ethnographic research conducted on the reservation with tribal members. Findings indicate that federal land policies act to effectively block direct land use. Tribal members have responded to policy in ways relative to the expression of cultural values, and the intent of policy has been undermined by a failure to fully understand the cultural context of the reservation. The discussion interprets land use through the themes of policy obstacles, forced incorporation into the world-system, and resistance via cultural sovereignty over land use decisions. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the Buder Center for American Indian Studies of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work as well as the Environmental Studies Program, for support in conducting research. -

Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm

[Expositions 6.1 (2012) 29–40] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 Unnaturally Cruel: Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm CHRISTIAN DIEHM University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point In 2010, over nine billion animals were killed in the United States for human consumption. This included nearly 1 million calves, 2.5 million sheep and lambs, 34 million cattle, 110 million hogs, 242 million turkeys, and well over 8.7 billion chickens (USDA 2011a; 2011b). Though hundreds of slaughterhouses actively contributed to these totals, more than half of the cattle just mentioned were killed at just fourteen plants. A slightly greater percentage of hogs was killed at only twelve (USDA 2011a). Chickens were processed in a total of three hundred and ten federally inspected facilities (USDA 2011b), which means that if every facility operated at the same capacity, each would have slaughtered over fifty-three birds per minute (nearly one per second) in every minute of every day, adding up to more than twenty-eight million apiece over the course of twelve months.1 Incredible as these figures may seem, 2010 was an average year for agricultural animals. Indeed, for nearly a decade now the total number of birds and mammals killed annually in the US has come in at or above the nine billion mark, and such enormous totals are possible only by virtue of the existence of an equally enormous network of industrialized agricultural suppliers. These high-volume farming operations – dubbed “factory farms” by the general public, or “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)” by state and federal agencies – are defined by the ways in which they restrict animals’ movements and behaviors, locate more and more bodies in less and less space, and increasingly mechanize many aspects of traditional husbandry. -

The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap

bs_bs_banner Journal of Applied Philosophy,Vol.31, No. 2, 2014 doi: 10.1111/japp.12051 The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap OSCAR HORTA ABSTRACT The argument from species overlap has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics and speciesism. However, there has been much confusion regarding what the argument proves and what it does not prove, and regarding the views it challenges.This article intends to clarify these confusions, and to show that the name most often used for this argument (‘the argument from marginal cases’) reflects and reinforces these misunderstandings.The article claims that the argument questions not only those defences of anthropocentrism that appeal to capacities believed to be typically human, but also those that appeal to special relations between humans. This means the scope of the argument is far wider than has been thought thus far. Finally, the article claims that, even if the argument cannot prove by itself that we should not disregard the interests of nonhuman animals, it provides us with strong reasons to do so, since the argument does prove that no defence of anthropocentrism appealing to non-definitional and testable criteria succeeds. 1. Introduction The argument from species overlap, which has also been called — misleadingly, I will argue — the argument from marginal cases, points out that the criteria that are com- monly used to deprive nonhuman animals of moral consideration fail to draw a line between human beings and other sentient animals, since there are also humans who fail to satisfy them.1 This argument has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics for two purposes. -

Living with Animals Conference Co-Organized by Robert W. Mitchell, Radhika N

Living with Animals Conference Co-organized by Robert W. Mitchell, Radhika N. Makecha, & Michał Piotr Pręgowski Eastern Kentucky University, 19-21 March 2015 Cover design: Kasey L. Morris Conference overview Each day begins with a keynote speaker, and follows with two tracks (in separate locations) that will run concurrently. Breakfast foods and coffee/tea/water will be available prior to the morning keynotes. Coffee breaks (i.e., snacks and coffee/tea/water) are scheduled between sequential groups of talks. Thus, for example, if one session is from 9:05-10:15, and the next session is 10:40-11:40, there is a coffee break from 10:15-10:40. Drinks and edibles should be visible at or near the entry to the rooms where talks are held. Book display: Throughout the conference in Library Room 201, there is a book display. Several university presses have generously provided books for your perusal (as well as order sheets), and some conference participants will be displaying their books as well. Thursday features the “Living with Horses” sessions, as well as concurrent sessions, and has an optional (pre-paid) trip to Berea for shopping and dinner at the Historic Boone Tavern Restaurant. Friday features the “Teaching with Animals” sessions throughout the morning and early afternoon (which includes a boxed lunch during panel discussions and a movie showing and discussion); “Living with Animals” sessions continuing in the late afternoon, and a Conference Dinner at Masala Indian restaurant. Saturday includes “Living with Animals” sessions throughout the day and Poster Presentations during a buffet lunch. In addition, there is the optional trip to the White Hall State Historic Site (you pay when you arrive at the site). -

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 Credits) Course Description

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 credits) Course Description: This course focuses on theories of morality rather than on contemporary moral issues (that is the topic of PHIL 120). That means that we will primarily be preoccupied with exploring what it means for an action—or a person—to be “good”. We will attempt to answer this question by looking at a mix of historical and contemporary texts primarily drawn from the Western European tradition, but also including some works from China and pre-colonial central America. We will begin by asking whether there are any universal and objectively valid moral rules, and chart several attempts to answer in both the affirmative and the negative: relativism, egoism, virtue ethics, consequentialism, deontology, the ethics of care, and contractarianism. We will consider the relationship between morality and the law, and whether morality is linked to human happiness. Finally, we will consider arguments for and against the idea that moral facts actually exist. Schedule of Readings Week 1 Introduction What are we trying to do? Charles L. Stevenson – The Nature of Ethical Disagreement Tom Regan – How Not to Answer Moral Questions Week 2 Relativism What counts as good depends on the moral standards of the group doing the evaluating. Mary Midgley – Trying Out One’s New Sword Martha Nussbaum – Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation Plato – The Myth of Gyges (Republic II) Week 3 Egoism What’s good is just what’s good for me. Mencius – Mengzi (excerpts) James Rachels – Egoism and Moral Skepticism Week 4 Virtue Ethics Morality depends on having a virtuous character. -

Review Of" Science and Poetry" by M. Midgley

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 10-1-2003 Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley Hans Oberdiek Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hans Oberdiek. (2003). "Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley". Ethics. Volume 114, Issue 1. 187-189. DOI: 10.1086/376710 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/121 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Midgley, Science and Poetry Science and Poetry by Mary. Midgley, Review by: Reviewed by Hans Oberdiek Ethics, Vol. 114, No. 1 (October 2003), pp. 187-189 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/376710 . Accessed: 09/06/2015 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics. -

Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics

Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics Gonzalo Villanueva Sophia International Journal of Philosophy and Traditions ISSN 0038-1527 SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0597-6 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0597-6 Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics Gonzalo Villanueva1 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2017 Keywords Animal ethics . Moral status of animals . Peter Singer. Animal liberation Peter Singer’s 1975 book Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals has been described as ‘the Bible’ of the modern animal movement.1 Singer’s unrhetorical and unemotional arguments radically departed from previous conceptions of animal ethics. He moved beyond the animal welfare tradition of ‘kindness’ and ‘compassion’ to articulate a non-anthropocentric utilitarian philosophy based on equal- ity and interests. After the publication of Animal Liberation, an ‘avalanche of animal rights literature’ appeared.2 A prolific amount of work focused on the moral status of animals, and the ‘animal question’ has been given serious consideration across a broad range of disciplines.