Jm Coetzee and Animal Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are Illegal Direct Actions by Animal Rights Activists Ethically Vigilante?

260 BETWEEN THE SPECIES Is the Radical Animal Rights Movement Ethically Vigilante? ABSTRACT Following contentious debates around the status and justifiability of illegal direct actions by animal rights activists, we introduce a here- tofore unexplored perspective that argues they are neither terrorist nor civilly disobedient but ethically vigilante. Radical animal rights movement (RARM) activists are vigilantes for vulnerable animals and their rights. Hence, draconian measures by the constitutional state against RARM vigilantes are both disproportionate and ille- gitimate. The state owes standing and toleration to such principled vigilantes, even though they are self-avowed anarchists and anti-stat- ists—unlike civil disobedients—repudiating allegiance to the con- stitutional order. This requires the state to acknowledge the ethical nature of challenges to its present regime of toleration, which assigns special standing to illegal actions in defense of human equality, but not equality and justice between humans and animals. Michael Allen East Tennessee State University Erica von Essen Environmental Communications Division Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Volume 22, Issue 1 Fall 2018 http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/bts/ 261 Michael Allen and Erica von Essen Introduction We explore the normative status of illegal actions under- taken by the Radical Animal Rights Movement (RARM), such as animal rescue, trespass, and sabotage as well as confronta- tion and intimidation. RARM typically characterizes these ac- tions as examples of direct action rather than civil disobedience (Milligan 2015, Pellow 2014). Moreover, many RARM activ- ists position themselves as politically anarchist, anti-statist, and anti-capitalist (Best 2014, Pellow 2014). Indeed, the US and UK take these self-presentations at face value, responding to RARM by introducing increasingly draconian legislation that treats them as terrorists (Best 2014, McCausland, O’Sullivan and Brenton 2013, O’Sullivan 2011, Pellow 2014). -

Animal Farm" Is the Story of a Farm Where the Animals Expelled Their

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/32376 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Vugts, Berrie Title: The case against animal rights : a literary intervention Issue Date: 2015-03-18 Introduction The last four decades have shown an especially intense and thorough academic reflection on the relation between man and animal. This is evidenced by the rapid growth of journals on the question of the animal within the fields of the humanities and social sciences worldwide.1 Yet also outside the academy animals now seem to preoccupy the popular mindset more than ever before. In 2002, the Netherlands was the first country in the world where a political party was established (the so-called “Partij voor de Dieren” or PvdD: Party for the Animals) that focused predominantly on animal issues. Heated discussions about factory-farming, the related spread of diseases (BSE/Q Fever), hunting and fishing practices, the inbreeding of domestic animals, are now commonplace. Animals, as we tend to call a large range of incredibly diverse creatures, come to us in many different ways. We encounter them as our pets and on our plates, animation movies dominate the charts and artists in sometimes rather experimental genres engage in the question of the animal.2 Globally speaking, animals might be considered key players in the climate debate insofar as the alarming rate of extinction of certain species is often taken to be indicative of our feeble efforts at preserving what is commonly referred to as “nature.” At the same time, these rates serve, albeit indirectly, as a grim reminder of the possible end of human existence itself. -

"Go Veg" Campaigns of US Animal Rights Organizations

Society and Animals 18 (2010) 163-182 brill.nl/soan Framing Animal Rights in the “Go Veg” Campaigns of U.S. Animal Rights Organizations Carrie Packwood Freeman Georgia State University [email protected] Abstract How much do animal rights activists talk about animal rights when they attempt to persuade America’s meat-lovers to stop eating nonhuman animals? Th is study serves as the basis for a unique evaluation and categorization of problems and solutions as framed by fi ve major U.S. animal rights organizations in their vegan/food campaigns. Th e fi ndings reveal that the organiza- tions framed the problems as: cruelty and suff ering; commodifi cation; harm to humans and the environment; and needless killing. To solve problems largely blamed on factory farming, activists asked consumers to become “vegetarian” (meaning vegan) or to reduce animal product con- sumption, some requesting “humane” reforms. While certain messages supported animal rights, promoting veganism and respect for animals’ subject status, many frames used animal welfare ideology to achieve rights solutions, conservatively avoiding a direct challenge to the dominant human/animal dualism. In support of ideological authenticity, this paper recommends that vegan campaigns emphasize justice, respect, life, freedom, environmental responsibility, and a shared animality. Keywords animal rights, campaigns, farm animal, framing, ideology, vegan, vegetarian How much do or should animal rights activists talk about animal rights when they attempt to persuade America’s meat-lovers to stop eating animals? As participants in a counterhegemonic social movement, animal rights organiza- tions are faced with the discursive challenge of redefi ning accepted practices, such as farming and eating nonhuman animals, as socially unacceptable practices. -

Lay Persons and Community Values in Reviewing Animal Experimentation Jeff Leslie [email protected]

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2006 | Issue 1 Article 5 Lay Persons and Community Values in Reviewing Animal Experimentation Jeff Leslie [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Recommended Citation Leslie, Jeff () "Lay Persons and Community Values in Reviewing Animal Experimentation," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2006: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2006/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lay Persons and Community Values in Reviewing Animal Experimentation Jeff Lesliet Is it morally acceptable to use animals in scientific experi- ments that will not benefit those animals, but instead solely benefit people? Most people would say yes; but at the same time most would view the use of animals as a regrettable necessity, to be pursued only when the benefits to people outweigh the harm to the animals, and only after everything possible is done to minimize that harm. Identifying benefits and harms may require specialized scientific and technological understanding, to be sure, but evaluating the tradeoff between them requires not technical expertise, but rather the capacity to make difficult moral judg- ments. We do not usually think of moral judgments as the unique terrain of any particular set of professionals or experts. Anyone capable of ethical reasoning has an equal claim to exper- tise, and a pluralistic society can be expected to exhibit a wide range of moral beliefs. -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

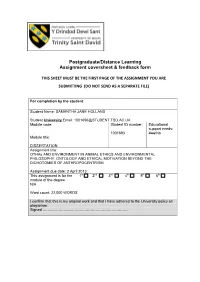

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

Teaching the Novel BEFORE, During After

97 U NIT P LAN: T EACHING T HE B ROTHERS K ARAMAZOV Chapter / Pages Teaching strategy / Learning activity AP AUDIT ELEMENT(S): KNOWLEDGE What students should know actively: What students should be able to recognize: SKILLS What students should be able to do: HABITS What students should do habitually: 98 Works Appearing on Suggestion Lists for “Question 3” Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Examination: 1971-2011 26 7 The Little Foxes Invisible Man All the King’s Men Middlemarch 22 All the Pretty Horses Pygmalion Wuthering Heights Candide A Tale of Two Cities The Crucible To the Lighthouse 18 Cry Beloved Country Twelfth Night Crime and Punishment Equus Typical American Jane Eyre Lord Jim The Women of Brewster Place 17 Madame Bovary 3 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Mayor of Casterbridge Alias Grace Great Expectations The Portrait of a Lady An American Tragedy Heart of Darkness The Sound and the Fury The American The Tempest 16 The Bluest Eye King Lear Waiting for Godot The Bonesetter's Daughter Moby-Dick Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The Catcher in the Rye Daisy Miller 15 6 David Copperfield The Great Gatsby Bless Me, Ultima Emma A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man The Cherry Orchard A Farewell to Arms The Scarlet Letter Ethan Frome Gulliver’s Travels Going After Cacciato 14 Hamlet The Handmaid’s Tale The Awakening Hedda Gabler Hard Times 13 Macbeth Henry IV, Part I Their Eyes Were Watching God Major Barbara House Made of Dawn Medea The House of Mirth 12 The Merchant of Venice To Kill a Mockingbird Beloved Moll Flanders The Kite Runner Catch-22 Mrs Dalloway Long Day’s Journey into Night Light in August Murder in the Cathedral Lord of the Flies 11 The Piano Lesson Mansfield Park As I Lay Dying Pride and Prejudice Master Harold” . -

The Great Ape Project — and Beyond*

The Great Ape Project — and Beyond* PAOLA CAVALIERI & PETER SINGER Why the Project? Aristotle refers to human slaves as 'animated property'. The phrase exactly describes the current status of nonhuman animals. Human slavery therefore presents an enlightening parallel to this situation. We shall explore this parallel in order to single out a past response to human slavery that may suggest a suitable way of responding to present-day animal slavery. Not long ago such a parallel would have been considered outrageous. Recently, however, there has been growing recognition of the claim that a sound ethic must be free of bias or arbitrary discrimination based in favour of our own species. This recognition makes possible a more impartial appraisal of the exploitative practices that mark our civilisation. Slavery in the ancient world has been the subject of a lively debate among historians. How did it arise? Why did it end? Was there a characteristic 'slave mode of production'? We do not need to go into all these disputes. We shall focus instead on the distinctive element of slavery: the fact that the human being becomes property in the strict sense of the term. This is sometimes referred to as 'chattel slavery' - a term that stresses the parallel between the human institution, and the ownership of animals, for the term 'cattle' is derived from 'chattel'. Slave societies are those societies of which chattel slavery is a major feature. They are relatively rare in human history. The best known examples existed in the ancient world, and in North and Central America after European colonisation. -

Western Civilisation 'Maintains Itself By

Western Civilisation ‘maintains itself by banishing Others (nature, animals, women, children) to the margin’.1 How do Notions of Alterity and/or Marginalisation Feature in the Representation of Animals? Georgia Horne Humans’ relationship with animals is a complexly mutable one, with the parameters of distinction being repeatedly rethought and redrawn by thinkers from a range of disciplines. The protean nature of these irreconcilable views is apparent given how, as observed by John Berger, throughout history animals have been concurrently bred yet sacrificed, subjected to suffering yet worshipped in idolatry.2 Accordingly, animals have continuously occupied a liminal space both above and below (but never with) man, a form of existential dualism reflective of the seemingly irresolvable struggle of where to place them in relation to humans. The site of difference between humans and other animals is where we derive our ontological concepts of humanity and animality and thus, ultimately, our place in the world as one species amongst others (an admittedly anthropocentric telos). Traditionally, ontological discourse on this issue has been dominated by an animal-human dichotomy, wherein the subjects are defined in opposition to each other.3 The privation of certain attributes are cited as evidence for this polarity, with philosophers such as Kant, Descartes and Aristotle citing humans’ capacity to reason as the qualifying criterion that simultaneously demarcates humans from animals, and endows us with a superiority over them. This binary contradistinction is threatened in Franz Kafka’s ‘A Report to an Academy’, which utilises various postcolonial narrative strategies to obfuscate the human-animal distinction, destabilising the West’s confident certainty in the Otherness of animals, and complicating the ethics of using animals’ assumed alterity to justify their marginalisation and mistreatment. -

George Bernard Shaw, the Fabian Society, and Reconstructionist Education Policy: the London School of Economics and Political Science

George Bernard Shaw, the Fabian Society, and Reconstructionist Education Policy: the London School of Economics and Political Science Jim McKernan East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA “He who can does, He who cannot teaches” (G.B. Shaw) Introduction When four members of the Executive Committee of the newly founded Fabian Society 1 met at Sidney Webb’s summer house at Borough Farm, near Godalming, Surrey, on the morning of 4 August, 1894 there was exciting news. The four left-wing intellectual radicals present were: Beatrice and Sidney Webb, Graham Wallas, (of the London School Board) and George Bernard Shaw. Sidney told the breakfast group of a letter he had received the previous day from Henry Hunt Hutchinson, a Derby solicitor who left his estate, a sum of ten thousand pounds sterling, to be used by the Fabian Society for its purposes. It appears that Sidney Webb probably initiated the idea of a London Economics Research School, but had the sound practical support and advice of Shaw and later, the financial support of Shaw’s wife, Charlotte Frances Payne-Townshend, an Irishwoman from Derry, County Cork. This paper explores the social reconstructionist educational and social policies employed by both the Webbs and George Bernard Shaw in establishing the London School of Economics and Political Science as a force to research and solve fundamental social problems like poverty in the United Kingdom in the late Nineteenth Century. That schools might function as agencies for dealing with the reformation of socio-economic problems has been a prime tenet of reconstructionist educational theory . 2 Social reconstructionist thought as an educational policy emerged in the USA from the time of the Great Depression of the 1930’s until the Civil Rights period of the 1960’s and many see it as a pre-cursor to critical theory in education. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

European Book Suggestions from Joanneke Elliott, African Studies and West European Studies Librarian, UNC-CH, with Additions from Various Sources

European Book Suggestions from Joanneke Elliott, African Studies and West European Studies Librarian, UNC-CH, with additions from various sources Albania Three Elegies for Kosovo by Ismail Kadare Summary: This slim volume tells the tale of a band of singers on the infamous Field of Blackbirds as the medieval Serbian state is defeated by the Ottoman army. Belgium Het moois dat we delen (not yet translated) by Ish Ait Hamou. Summary: Soumia and Luc live in the same neighborhood, but they don't know each other. She is desperately trying to leave the past behind. He lives in and with the past. When they get to know each other by chance, they are faced with difficult decisions. Mevrouw Verona daalt de heuvel af/Madame Verona Comes Down the Hill by Dimitri Verhulst. Summary: Years ago, Madame Verona and her husband built a home for themselves on a hill in a forest above a small village. There they lived in isolation, practicing their music, and chopping wood to see them through the cold winters. When Mr. Verona died, the locals might have expected that the legendary beauty would return to the village, but Madame Verona had enough wood to keep her warm during the years it would take to make a cello—the instrument her husband loved—and in the meantime she had her dogs for company. And then one cold February morning, when the last log has burned, Madame Verona sets off down the village path, with her cello and her memories, knowing that she will have no strength to climb the hill again.