The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are Illegal Direct Actions by Animal Rights Activists Ethically Vigilante?

260 BETWEEN THE SPECIES Is the Radical Animal Rights Movement Ethically Vigilante? ABSTRACT Following contentious debates around the status and justifiability of illegal direct actions by animal rights activists, we introduce a here- tofore unexplored perspective that argues they are neither terrorist nor civilly disobedient but ethically vigilante. Radical animal rights movement (RARM) activists are vigilantes for vulnerable animals and their rights. Hence, draconian measures by the constitutional state against RARM vigilantes are both disproportionate and ille- gitimate. The state owes standing and toleration to such principled vigilantes, even though they are self-avowed anarchists and anti-stat- ists—unlike civil disobedients—repudiating allegiance to the con- stitutional order. This requires the state to acknowledge the ethical nature of challenges to its present regime of toleration, which assigns special standing to illegal actions in defense of human equality, but not equality and justice between humans and animals. Michael Allen East Tennessee State University Erica von Essen Environmental Communications Division Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Volume 22, Issue 1 Fall 2018 http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/bts/ 261 Michael Allen and Erica von Essen Introduction We explore the normative status of illegal actions under- taken by the Radical Animal Rights Movement (RARM), such as animal rescue, trespass, and sabotage as well as confronta- tion and intimidation. RARM typically characterizes these ac- tions as examples of direct action rather than civil disobedience (Milligan 2015, Pellow 2014). Moreover, many RARM activ- ists position themselves as politically anarchist, anti-statist, and anti-capitalist (Best 2014, Pellow 2014). Indeed, the US and UK take these self-presentations at face value, responding to RARM by introducing increasingly draconian legislation that treats them as terrorists (Best 2014, McCausland, O’Sullivan and Brenton 2013, O’Sullivan 2011, Pellow 2014). -

Climate Change Impacts on Free-Living Nonhuman Animals

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Redfame Publishing: E-Journals Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 7, No. 1; June 2019 ISSN: 2325-8071 E-ISSN: 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Climate Change Impacts on Free-Living Nonhuman Animals. Challenges for Media and Communication Ethics Núria Almiron1, Catia Faria2 1Department of Communication, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Roc Boronat, 138 08018 Barcelona, Spain 2Centro de Ética, Política e Sociedade, ILCH, Universidade do Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal Correspondence: Núria Almiron, Department of Communication, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Roc Boronat, 138 08018 Barcelona, Spain. Received: April 21, 2019 Accepted: May 21, 2019 Online Published: May 29, 2019 doi:10.11114/smc.v7i1.4305 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v7i1.4305 Abstract The mainstream discussion regarding climate change in politics, public opinion and the media has focused almost exclusively on preventing the harms humans suffer due to global warming. Yet climate change is already having an impact on free-living nonhumans, which raises unexplored ethical concerns from a nondiscriminatory point of view. This paper discusses the inherent ethical challenge of climate change impacts on nonhuman animals living in nature and argues that the media and communication ethics cannot avoid addressing the issue. The paper further argues that media ethics needs to mirror animal ethics by rejecting moral anthropocentrism. Keywords: media ethics, egalitarianism, climate change, wildlife, anthropocentrism 1. Introduction Since evidence of climate change was brought to light by the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1990, concerns regarding the issue have focused almost exclusively on preventing the harm humans suffer due to global warming. -

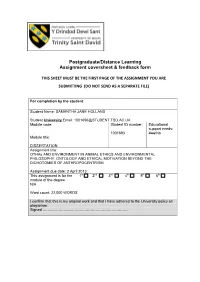

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

Ethics, Agency & Love

Ethics, Agency & Love for Bryn Browne Department of Philosophy, University of Wales Lampeter Speciesism - Arguments for Whom? Camilla Kronqvist Please do not quote without permission! Since the publication of Animal Liberation by Peter Singer in 1975 there has been an upshot of literature concerned with the moral standing of animals and our attitudes and reactions towards them. The starting point for most of these discussions can mainly be found in the notion of speciesism, a term that originally was introduced by Richard Ryder but that has become more widely spread with the writings of Peter Singer. It is also Singer that I am discussing in this essay although many other philosophers have brought forward similar ideas. The idea that lies behind this notion is basically that we as human beings have prejudices in our attitudes towards animals and that we discriminate against them on grounds that are unacceptable in a society that stresses the importance of equality. The line that we draw between human beings, or members of the species Homo Sapiens as Singer prefers to put it, and animals is as arbitrary as the lines that previously have been drawn on the basis of sex or race. It is not a distinction that is based on any factual differences between the species but simply on the sense of superiority we seem to pride ourselves in with regard to our own species. Allowing the species of a being to be the determining factor for our ethical reactions towards is, according to the argument, as bad as letting sex or race play the same part. -

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 11 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Steven Best, Chief Editor Pg. 2-3 Introducing Critical Animal Studies Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 4-5 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Pg. 6-19 Animal Rights Law: Fundamentalism versus Pragmatism David Sztybel Pg. 20-54 Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are Anthony J. Nocella II Pg. 55-64 The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: New, Improved, and ACLU-Approved Steven Best Pg. 65-81 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, by Peter Singer ed. (2005) Reviewed by Matthew Calarco Pg. 82-87 Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy, by Matthew Scully (2003) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 88-91 Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II, eds. (2004) Reviewed by Lauren E. Eastwood Pg. 92 Introduction Welcome to the sixth issue of our journal. You’ll first notice that our journal and site has undergone a name change. The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs is now the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, and the Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal is now the Journal for Critical Animal Studies. The name changes, decided through discussion among our board members, were prompted by both philosophical and pragmatic motivations. -

Equality, Priority and Nonhuman Animals*

Equality, Priority and Catia Faria Nonhuman Animals* Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Department of Law [email protected] http://upf.academia.edu/catiafaria Igualdad, prioridad y animales no humanos ABSTRACT: This paper assesses the implications of egali- RESUMEN: Este artículo analiza las implicaciones del iguali- tarianism and prioritarianism for the consideration of tarismo y del prioritarismo en lo que refiere a la conside- nonhuman animals. These implications have been often ración de los animales no humanos. Estas implicaciones overlooked. The paper argues that neither egalitarianism han sido comúnmente pasadas por alto. Este artículo de- nor prioritarianism can consistently deprive nonhuman fenderá que ni el igualitarismo ni el prioritarismo pueden animals of moral consideration. If you really are an egali- privar de forma consistente de consideración moral a los tarian (or a prioritarian) you are necessarily committed animales no humanos. Si realmente alguien es igualitaris- both to the rejection of speciesism and to assigning prior- ta (o prioritarista) ha de tener necesariamente una posi- ity to the interests of nonhuman animals, since they are ción de rechazo del especismo, y estar a favor de asignar the worst-off. From this, important practical consequen- prioridad a los intereses de los animales no humanos, ces follow for the improvement of the current situation of dado que estos son los que están peor. De aquí se siguen nonhuman animals. importantes consecuencias prácticas para la mejora de la situación actual de los animales no humanos. KEYWORDS: egalitarianism, prioritarianism, nonhuman ani- PALABRAS-CLAVE: igualitarismo, prioritarismo, animales no hu- mals, speciesism, equality manos, especismo, igualdad 1. Introduction It is commonly assumed that human beings should be given preferential moral consideration, if not absolute priority, over the members of other species. -

Living with Animals Conference Co-Organized by Robert W. Mitchell, Radhika N

Living with Animals Conference Co-organized by Robert W. Mitchell, Radhika N. Makecha, & Michał Piotr Pręgowski Eastern Kentucky University, 19-21 March 2015 Cover design: Kasey L. Morris Conference overview Each day begins with a keynote speaker, and follows with two tracks (in separate locations) that will run concurrently. Breakfast foods and coffee/tea/water will be available prior to the morning keynotes. Coffee breaks (i.e., snacks and coffee/tea/water) are scheduled between sequential groups of talks. Thus, for example, if one session is from 9:05-10:15, and the next session is 10:40-11:40, there is a coffee break from 10:15-10:40. Drinks and edibles should be visible at or near the entry to the rooms where talks are held. Book display: Throughout the conference in Library Room 201, there is a book display. Several university presses have generously provided books for your perusal (as well as order sheets), and some conference participants will be displaying their books as well. Thursday features the “Living with Horses” sessions, as well as concurrent sessions, and has an optional (pre-paid) trip to Berea for shopping and dinner at the Historic Boone Tavern Restaurant. Friday features the “Teaching with Animals” sessions throughout the morning and early afternoon (which includes a boxed lunch during panel discussions and a movie showing and discussion); “Living with Animals” sessions continuing in the late afternoon, and a Conference Dinner at Masala Indian restaurant. Saturday includes “Living with Animals” sessions throughout the day and Poster Presentations during a buffet lunch. In addition, there is the optional trip to the White Hall State Historic Site (you pay when you arrive at the site). -

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 Credits) Course Description

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 credits) Course Description: This course focuses on theories of morality rather than on contemporary moral issues (that is the topic of PHIL 120). That means that we will primarily be preoccupied with exploring what it means for an action—or a person—to be “good”. We will attempt to answer this question by looking at a mix of historical and contemporary texts primarily drawn from the Western European tradition, but also including some works from China and pre-colonial central America. We will begin by asking whether there are any universal and objectively valid moral rules, and chart several attempts to answer in both the affirmative and the negative: relativism, egoism, virtue ethics, consequentialism, deontology, the ethics of care, and contractarianism. We will consider the relationship between morality and the law, and whether morality is linked to human happiness. Finally, we will consider arguments for and against the idea that moral facts actually exist. Schedule of Readings Week 1 Introduction What are we trying to do? Charles L. Stevenson – The Nature of Ethical Disagreement Tom Regan – How Not to Answer Moral Questions Week 2 Relativism What counts as good depends on the moral standards of the group doing the evaluating. Mary Midgley – Trying Out One’s New Sword Martha Nussbaum – Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation Plato – The Myth of Gyges (Republic II) Week 3 Egoism What’s good is just what’s good for me. Mencius – Mengzi (excerpts) James Rachels – Egoism and Moral Skepticism Week 4 Virtue Ethics Morality depends on having a virtuous character. -

Review Of" Science and Poetry" by M. Midgley

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 10-1-2003 Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley Hans Oberdiek Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hans Oberdiek. (2003). "Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley". Ethics. Volume 114, Issue 1. 187-189. DOI: 10.1086/376710 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/121 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Midgley, Science and Poetry Science and Poetry by Mary. Midgley, Review by: Reviewed by Hans Oberdiek Ethics, Vol. 114, No. 1 (October 2003), pp. 187-189 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/376710 . Accessed: 09/06/2015 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics. -

Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics

Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics Gonzalo Villanueva Sophia International Journal of Philosophy and Traditions ISSN 0038-1527 SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0597-6 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0597-6 Against Animal Liberation? Peter Singer and His Critics Gonzalo Villanueva1 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2017 Keywords Animal ethics . Moral status of animals . Peter Singer. Animal liberation Peter Singer’s 1975 book Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals has been described as ‘the Bible’ of the modern animal movement.1 Singer’s unrhetorical and unemotional arguments radically departed from previous conceptions of animal ethics. He moved beyond the animal welfare tradition of ‘kindness’ and ‘compassion’ to articulate a non-anthropocentric utilitarian philosophy based on equal- ity and interests. After the publication of Animal Liberation, an ‘avalanche of animal rights literature’ appeared.2 A prolific amount of work focused on the moral status of animals, and the ‘animal question’ has been given serious consideration across a broad range of disciplines.