Crystal Structure of the DNA-Binding Domain of Myelin-Gene Regulatory Factor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interaction of Functional NPC1 Gene Polymorphism with Smoking On

Ma et al. BMC Medical Genetics 2010, 11:149 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/11/149 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Interaction of functional NPC1 gene Polymorphism with smoking on coronary heart disease Weiwei Ma1, Jing Xu1, Qianqian Wang2, Ying Xin1, Lin Zhang1, Xinxin Zheng1, Hu Wang1, Kai Sun1, Rutai Hui1, Xiaohong Huang2* Abstract Background: The protein of Niemann-pick type C1 gene (NPC1) is known to facilitate the egress of cholesterol and other lipids from late endosomes and lysosomes to other cellular compartments. This study aims to investigate whether the genetic variation in NPC1 is associated with risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and to detect whether NPC1 might interact with smoking on the risk of CHD. Methods: We performed a case-control study, including 873 patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and 864 subjects without CHD as control. Polymorphisms of NPC1 gene were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) -restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Results: A tag-SNP rs1805081 (+644A > G) in NPC1 was identified. The G allele of the +644 locus showed reduced risk of CHD than wild-type genotype in Chinese population (recessive model GG vs. AG+AA: odds ratio [OR] 0.647, 95% CI 0.428 to 0.980, P = 0.039; additive model GG vs. AG vs. AA: OR 0.847, 95% CI 0.718 to 0.998, P = 0.0471). Moreover in smokers, the G-allele carriers had reduced risk of CHD compared with A-allele carries (OR 0.552, 95% CI 0.311 to 0.979, P = 0.0421). Conclusions: The results of the present study suggest that NPC1 variants seem to be contributors to coronary heart disease occurrence in Chinese population. -

Investigation of Candidate Genes and Mechanisms Underlying Obesity

Prashanth et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:80 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00718-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules G. Prashanth1 , Basavaraj Vastrad2 , Anandkumar Tengli3 , Chanabasayya Vastrad4* and Iranna Kotturshetti5 Abstract Background: Obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder ; however, the etiology of obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus remains largely unknown. There is an urgent need to further broaden the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods: To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that might play essential roles in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus, the publicly available expression profiling by high throughput sequencing data (GSE143319) was downloaded and screened for DEGs. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The protein - protein interaction network, miRNA - target genes regulatory network and TF-target gene regulatory network were constructed and analyzed for identification of hub and target genes. The hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and RT- PCR analysis. Finally, a molecular docking study was performed on over expressed proteins to predict the target small drug molecules. Results: A total of 820 DEGs were identified between -

Cell Reprogramming Technologies for Treatment And

CELL REPROGRAMMING TECHNOLOGIES FOR TREATMENT AND UNDERSTANDING OF GENETIC DISORDERS OF MYELIN by ANGELA MARIE LAGER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis advisor: Paul J Tesar, PhD Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Angela Marie Lager Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. (signed) Ronald A Conlon, PhD (Committee Chair) Paul J Tesar, PhD (Advisor) Craig A Hodges, PhD Warren J Alilain, PhD (date) 31 March 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained from any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….1 List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..7 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………..8 Chapter 1: Introduction and Background………………………………………..11 1.1 Overview of mammalian oligodendrocyte development in the spinal cord and myelination of the central nervous system…………………..11 1.1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………..11 1.1.2 The establishment of the neuroectoderm and ventral formation of the neural tube…………………………………..12 1.1.3 Ventral patterning of the neural tube and specification of the pMN domain in the spinal cord……………………………….15 1.1.4 Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell production through the process of gliogenesis ………………………………………..16 1.1.5 Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell to oligodendrocyte differentiation…………………………………………………...22 -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

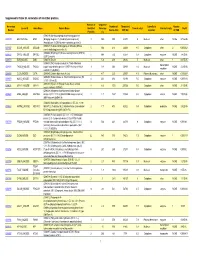

Table SI. Primer List of Genes Used for Reverse Transcription‑Quantitative PCR Validation

Table SI. Primer list of genes used for reverse transcription‑quantitative PCR validation. Genes Forward (5'‑3') Reverse (5'‑3') Length COL1A1 AGTGGTTTGGATGGTGCCAA GCACCATCATTTCCACGAGC 170 COL6A1 CCCCTCCCCACTCATCACTA CGAATCAGGTTGGTCGGGAA 65 COL2A1 GGTCCTGCAGGTGAACCC CTCTGTCTCCTTGCTTGCCA 181 DCT CTACGAAACCAGGATGACCGT ACCATCATTGGTTTGCCTTTCA 192 PDE4D ATTGCCCACGATAGCTGCTC GCAGATGTGCCATTGTCCAC 181 RP11‑428C19.4 ACGCTAGAAACAGTGGTGCG AATCCCCGGAAAGATCCAGC 179 GPC‑AS2 TCTCAACTCCCCTCCTTCGAG TTACATTTCCCGGCCCATCTC 151 XLOC_110310 AGTGGTAGGGCAAGTCCTCT CGTGGTGGGATTCAAAGGGA 187 COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1; COL6A1, collagen type VI, alpha 1; COL2A1, collagen type II alpha 1; DCT, dopachrome tautomerase; PDE4D, phosphodiesterase 4D cAMP‑specific. Table SII. The differentially expressed mRNAs in the ParoAF_Control group. Gene ID logFC P‑Value Symbol Description ENSG00000165480 ‑6.4838 8.32E‑12 SKA3 Spindle and kinetochore associated complex subunit 3 ENSG00000165424 ‑6.43924 0.002056 ZCCHC24 Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 24 ENSG00000182836 ‑6.20215 0.000817 PLCXD3 Phosphatidylinositol‑specific phospholipase C, X domain containing 3 ENSG00000174358 ‑5.79775 0.029093 SLC6A19 Solute carrier family 6 (neutral amino acid transporter), member 19 ENSG00000168916 ‑5.761 0.004046 ZNF608 Zinc finger protein 608 ENSG00000134343 ‑5.56371 0.01356 ANO3 Anoctamin 3 ENSG00000110400 ‑5.48194 0.004123 PVRL1 Poliovirus receptor‑related 1 (herpesvirus entry mediator C) ENSG00000124882 ‑5.45849 0.022164 EREG Epiregulin ENSG00000113448 ‑5.41752 0.000577 PDE4D Phosphodiesterase -

Supporting Table S3 for PDF Maker

Supplemental Table S3. Annotation of identified proteins. Number of Sequence Accession Number of Theoretical Subcellular Number Locus ID Gene Name Protein Name Identified Coverage Theoretical pI Protein Family NSAF Number Amino Acid MW (Da) Location of TMD Peptides (%) (O08539) Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1 O08539 BIN1_MOUSE BIN1 (Bridging integrator 1) (Amphiphysin-like protein) 3 10.5 588 64470 5 Nucleus other NONE 5.73E-05 (Amphiphysin II) (SH3-domain-containing protein 9) (O08547) Vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b (SEC22 O08547 SC22B_MOUSE SEC22B 5 30.4 214 24609 8.5 Cytoplasm other 2 0.000262 vesicle-trafficking protein-like 1) (O08553) Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 (DRP-2) O08553 DPYL2_MOUSE DPYSL2 5 19.4 572 62278 6.4 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 7.85E-05 (ULIP 2 protein) O08579 EMD_MOUSE EMD (O08579) Emerin 1 5.8 259 29436 5 Nucleus other 1 8.67E-05 (O08583) THO complex subunit 4 (Tho4) (RNA and transcription O08583 THOC4_MOUSE THOC4 export factor-binding protein 1) (REF1-I) (Ally of AML-1 1 9.8 254 26809 11.2 Nucleus NONE 2.21E-05 regulator and LEF-1) (Aly/REF) O08585 CLCA_MOUSE CLTA (O08585) Clathrin light chain A (Lca) 2 4.7 235 25557 4.5 Plasma Membrane other NONE 0.000287 (O08600) Endonuclease G, mitochondrial precursor (EC O08600 NUCG_MOUSE ENDOG 4 23.1 294 32191 9.5 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 0.000134 3.1.30.-) (Endo G) (O08638) Myosin-11 (Myosin heavy chain, smooth O08638 MYH11_MOUSE MYH11 8 6.6 1972 227026 5.5 Cytoplasm other NONE 3.13E-05 muscle isoform) (SMMHC) (O08648) Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase -

Isolating the Role of Corticosterone in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Genomic Stress Response

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.330209; this version posted October 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Isolating the role of corticosterone in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal 2 genomic stress response 3 4 By: Suzanne H. Austin1, *, Rayna Harris1, April M. Booth1, Andrew S. Lang2, Victoria S. Farrar1, 5 Jesse S. Krause1, 3, Tyler A. Hallman4, Matthew MacManes2, and Rebecca M. Calisi1 6 7 1Department of Neurobiology, Physiology, and Behavior, University of California Davis, 1 8 Shields Avenue, Davis, CA, USA, 95616 9 2 Department of Molecular, Cellular and Biomedical Sciences, The University of New 10 Hampshire, 434 Gregg Hall, Durham, NH, USA, 03824 11 3 Department of Biology, University of Nevada, Reno, 1664 N. Virginia Street, Reno, NV, USA, 12 89557-0314 13 4 Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 104 Nash Hall, Corvallis, OR 14 97331 15 16 *Current address: 17 Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, 3029 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, OR, 18 USA, 97331; Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 104 Nash Hall, 19 Corvallis, OR 97331 20 21 22 23 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.330209; this version posted October 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Clinical-Biochemical Correlation in Molecularly Characterized Patients

September/October 2001 ⅐ Vol. 3 ⅐ No. 5 article Clinical-biochemical correlation in molecularly characterized patients with Niemann-Pick type C Vardiella Meiner, MD1, Shoshi Shpitzen, BSc2, Hanna Mandel, MD3, Aharon Klar, MD4, Ziva Ben-Neriah, MD1, Jol Zlotogora, MD, PhD5, Michal Sagi, PhD1, Alex Lossos, MD6, Ruth Bargal, MSc1, Vivy Sury, BSc1, Rivka Carmi, MD7, Eran Leitersdorf, MD2, and Marsha Zeigler, PhD1 Purpose: Niemann-Pick disease type C (NP-C) is an autosomal recessive lipid storage disease manifested by an impairment in cellular cholesterol homeostasis. The clinical phenotype of NP-C is extremely variable, ranging from an acute neonatal form to an adult late-onset presentation. To facilitate phenotype-genotype studies, we have analyzed multiple Israeli NP-C families. Methods: The severity of the disease was assessed by the age at onset, hepatic involvement, neurological deterioration, and cholesterol esterification studies. Screening of the entire NPC1 coding sequence allowed for molecular characterization and identification of disease causing mutations. Results: A total of nine NP-C index cases with mainly neurovisceral involvement were characterized. We demon- strated a possible link between the severity of the clinical phenotype and the cholesterol esterification levels in fibroblast cultures following 24 hours of in vitro cholesterol loading. In addition, we identified eight novel mutations in the NPC1 gene. Conclusions: Our results further support the clinical and allelic heterogeneity of NP-C and point to possible association between the clinical and the biochemical phenotype in distinct affected Israeli families. Genet Med 2001:3(5):343–348. Key Words: lipid storage disease, cholesterol esterification, mutation analyses, NPC1 gene, consanguineous marriage Niemann-Pick disease type C (NP-C) is an autosomal reces- of NP-C is extremely variable ranging from an acute neonatal sive lipid storage disease manifested by an impairment in cel- form, showing mainly liver involvement and rapid neurologic lular cholesterol homeostasis (OMIM number 257220). -

The NANOG Transcription Factor Induces Type 2 Deiodinase Expression and Regulates the Intracellular Activation of Thyroid Hormone in Keratinocyte Carcinomas

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S18 Supplementary Materials: The NANOG Transcription Factor Induces Type 2 Deiodinase Expression and Regulates the Intracellular Activation of Thyroid Hormone in Keratinocyte Carcinomas Annarita Nappi, Emery Di Cicco, Caterina Miro, Annunziata Gaetana Cicatiello, Serena Sagliocchi, Giuseppina Mancino, Raffaele Ambrosio, Cristina Luongo, Daniela Di Girolamo, Maria Angela De Stefano, Tommaso Porcelli, Mariano Stornaiuolo and Monica Dentice Figure S1. Strategy for the mutagenesis of Dio2 promoter. (A) Schematic representation of NANOG Binding Site within the Dio2 promoter region. (B) Schematic diagram for site‐directed mutagenesis of NANOG Binding Site on Dio2 promoter region by Recombinant PCR. (C) Representation of the mutated NANOG Binding Site on Dio2 promoter region. (D) Electropherogram of the NANOG Binding Site mutation within the Dio2 promoter. Cancers 2020, 12 S2 of S18 Figure S2. Strategy for the silencing of NANOG expression. (A) Cloning strategies for the generation of NANOG shRNA expression vectors. (B) Electropherograms of the NANOG shRNA sequences cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector. (C) Validation of effective NANOG down-modulation by two different NANOG shRNA vectors was assessed by Western Blot analysis of NANOG expression in BCC cells. (D) Quantification of NANOG protein levels versus Tubulin levels in the same experiment as in C is represented by histograms. Cancers 2020, 12 S3 of S18 Figure S3. The CD34+ cells are characterized by the expression of typical epithelial stemness genes. The mRNA levels of a panel of indicated stemness markers of epidermis were measured by Real Time PCR in the same experiment indicated in figure 3F and G. Cancers 2020, 12 S4 of S18 Figure S4. -

Application of Microrna Database Mining in Biomarker Discovery and Identification of Therapeutic Targets for Complex Disease

Article Application of microRNA Database Mining in Biomarker Discovery and Identification of Therapeutic Targets for Complex Disease Jennifer L. Major, Rushita A. Bagchi * and Julie Pires da Silva * Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.A.B.); [email protected] (J.P.d.S.) Supplementary Tables Methods Protoc. 2021, 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps4010005 www.mdpi.com/journal/mps Methods Protoc. 2021, 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps4010005 2 of 25 Table 1. List of all hsa-miRs identified by Human microRNA Disease Database (HMDD; v3.2) analysis. hsa-miRs were identified using the term “genetics” and “circulating” as input in HMDD. Targets CAD hsa-miR-1 Targets IR injury hsa-miR-423 Targets Obesity hsa-miR-499 hsa-miR-146a Circulating Obesity Genetics CAD hsa-miR-423 hsa-miR-146a Circulating CAD hsa-miR-149 hsa-miR-499 Circulating IR Injury hsa-miR-146a Circulating Obesity hsa-miR-122 Genetics Stroke Circulating CAD hsa-miR-122 Circulating Stroke hsa-miR-122 Genetics Obesity Circulating Stroke hsa-miR-26b hsa-miR-17 hsa-miR-223 Targets CAD hsa-miR-340 hsa-miR-34a hsa-miR-92a hsa-miR-126 Circulating Obesity Targets IR injury hsa-miR-21 hsa-miR-423 hsa-miR-126 hsa-miR-143 Targets Obesity hsa-miR-21 hsa-miR-223 hsa-miR-34a hsa-miR-17 Targets CAD hsa-miR-223 hsa-miR-92a hsa-miR-126 Targets IR injury hsa-miR-155 hsa-miR-21 Circulating CAD hsa-miR-126 hsa-miR-145 hsa-miR-21 Targets Obesity hsa-mir-223 hsa-mir-499 hsa-mir-574 Targets IR injury hsa-mir-21 Circulating IR injury Targets Obesity hsa-mir-21 Targets CAD hsa-mir-22 hsa-mir-133a Targets IR injury hsa-mir-155 hsa-mir-21 Circulating Stroke hsa-mir-145 hsa-mir-146b Targets Obesity hsa-mir-21 hsa-mir-29b Methods Protoc. -

Regulation of Cell Fate Decisions in the Developing Forebrain by DLX

Regulation of cell fate decisions in the developing forebrain by DLX transcription factors by Mikaela Nevin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Medical Sciences- Medical Genetics University of Alberta © Mikaela Nevin, 2020 Abstract Introduction The Dlx1/Dlx2 double knockout (DKO) mouse exhibits major defects in forebrain development including a block in differentiation and migration of GABAergic interneurons from the subpallium to the cortex. In addition, the Dlx1/Dlx2 DKO mouse generates more oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC) during forebrain development, and this occurs at the expense of interneuron generation. This phenotype suggests a role for DLX genes in mediating the neuronal-glial cell fate switch in the developing forebrain. Furthermore, expression of many oligodendroglial lineage genes is increased and occurs earlier in the DKO forebrain. As such, we hypothesized that DLX2 actively represses acquisition of oligodendroglial cell fate in a subset of forebrain neural progenitor cells by direct transcriptional repression of multiple genes required for oligodendroglial development. Here, I aimed to determine whether DLX2 represses expression of the oligodendroglial lineage genes Myt1 and Plp1 during forebrain development. In order to further characterise this gene regulatory network, I also investigated regulation of Plp1 by MYT1. I also investigated whether DLX2 may play a role in regulating progenitor cell fate in the pediatric brain tumour Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG). Methods Chromatin immunoprecipitation with a polyclonal DLX2 antibody was performed on E13.5 mouse forebrain chromatin to determine whether DLX2 occupied candidate promoter regulatory regions of the Myt1 and Plp1 promoters, and with an MYT1 antibody on E14.5 and E18.5 forebrain to determine if MYT1 occupied candidate regulatory regions of the Plp1 promoter.