1 Regenerating CNS Myelin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixing Old and Young: Enhancing Rejuvenation and Accelerating Aging

Mixing old and young: enhancing rejuvenation and accelerating aging Ashley Lau, … , James L. Kirkland, Stefan G. Tullius J Clin Invest. 2019;129(1):4-11. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI123946. Review Donor age and recipient age are factors that influence transplantation outcomes. Aside from age-associated differences in intrinsic graft function and alloimmune responses, the ability of young and old cells to exert either rejuvenating or aging effects extrinsically may also apply to the transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells or solid organ transplants. While the potential for rejuvenation mediated by the transfer of youthful cells is currently being explored for therapeutic applications, aspects that relate to accelerating aging are no less clinically significant. Those effects may be particularly relevant in transplantation with an age discrepancy between donor and recipient. Here, we review recent advances in understanding the mechanisms by which young and old cells modify their environments to promote rejuvenation- or aging-associated phenotypes. We discuss their relevance to clinical transplantation and highlight potential opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/123946/pdf REVIEW The Journal of Clinical Investigation Mixing old and young: enhancing rejuvenation and accelerating aging Ashley Lau,1 Brian K. Kennedy,2,3,4,5 James L. Kirkland,6 and Stefan G. Tullius1 1Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 2Departments of Biochemistry and Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. 3Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences, Singapore. 4Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore. -

REVIEW Organ Fabrication Using Pigs As an in Vivo Bioreactor

REVIEW Organ Fabrication Using Pigs as An in Vivo Bioreactor Eiji Kobayashi,1 Shugo Tohyama1,2 and Keiichi Fukuda2 1Department of Organ Fabrication, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan 2Department of Cardiology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan (Received for publication on May 23, 2019) (Revised for publication on July 15, 2019) (Accepted for publication on July 17, 2019) (Published online in advance on August 6, 2019) We present the most recent research results on the creation of pigs that can accept human cells. Pigs in which grafted human cells can flourish are essential for studies of the production of human organs in the pig and for verification of the efficacy of cells and tissues of human origin for use in regenerative therapy. First, against the background of a worldwide shortage of donor organs, the need for future medical technology to produce human organs for transplantation is discussed. We then describe proof- of-concept studies in small animals used to produce human organs. An overview of the history of studies examining the induction of immune tolerance by techniques involving fertilized animal eggs and the injection of human cells into fetuses or neonatal animals is also presented. Finally, current and future prospects for producing pigs that can accept human cells and tissues for experimental purposes are discussed. (DOI: 10.2302/kjm.2019-0006-OA; Keio J Med 69 (2) : 30–36, June 2020) Keywords: organ fabrication, donor shortage, in vivo bioreactor, pig, stem cell Introduction nor and has saved -

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Investigation of Candidate Genes and Mechanisms Underlying Obesity

Prashanth et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:80 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00718-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules G. Prashanth1 , Basavaraj Vastrad2 , Anandkumar Tengli3 , Chanabasayya Vastrad4* and Iranna Kotturshetti5 Abstract Background: Obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder ; however, the etiology of obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus remains largely unknown. There is an urgent need to further broaden the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods: To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that might play essential roles in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus, the publicly available expression profiling by high throughput sequencing data (GSE143319) was downloaded and screened for DEGs. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The protein - protein interaction network, miRNA - target genes regulatory network and TF-target gene regulatory network were constructed and analyzed for identification of hub and target genes. The hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and RT- PCR analysis. Finally, a molecular docking study was performed on over expressed proteins to predict the target small drug molecules. Results: A total of 820 DEGs were identified between -

Cell Reprogramming Technologies for Treatment And

CELL REPROGRAMMING TECHNOLOGIES FOR TREATMENT AND UNDERSTANDING OF GENETIC DISORDERS OF MYELIN by ANGELA MARIE LAGER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis advisor: Paul J Tesar, PhD Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Angela Marie Lager Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. (signed) Ronald A Conlon, PhD (Committee Chair) Paul J Tesar, PhD (Advisor) Craig A Hodges, PhD Warren J Alilain, PhD (date) 31 March 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained from any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….1 List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..7 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………..8 Chapter 1: Introduction and Background………………………………………..11 1.1 Overview of mammalian oligodendrocyte development in the spinal cord and myelination of the central nervous system…………………..11 1.1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………..11 1.1.2 The establishment of the neuroectoderm and ventral formation of the neural tube…………………………………..12 1.1.3 Ventral patterning of the neural tube and specification of the pMN domain in the spinal cord……………………………….15 1.1.4 Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell production through the process of gliogenesis ………………………………………..16 1.1.5 Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell to oligodendrocyte differentiation…………………………………………………...22 -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

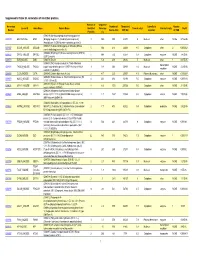

Table SI. Primer List of Genes Used for Reverse Transcription‑Quantitative PCR Validation

Table SI. Primer list of genes used for reverse transcription‑quantitative PCR validation. Genes Forward (5'‑3') Reverse (5'‑3') Length COL1A1 AGTGGTTTGGATGGTGCCAA GCACCATCATTTCCACGAGC 170 COL6A1 CCCCTCCCCACTCATCACTA CGAATCAGGTTGGTCGGGAA 65 COL2A1 GGTCCTGCAGGTGAACCC CTCTGTCTCCTTGCTTGCCA 181 DCT CTACGAAACCAGGATGACCGT ACCATCATTGGTTTGCCTTTCA 192 PDE4D ATTGCCCACGATAGCTGCTC GCAGATGTGCCATTGTCCAC 181 RP11‑428C19.4 ACGCTAGAAACAGTGGTGCG AATCCCCGGAAAGATCCAGC 179 GPC‑AS2 TCTCAACTCCCCTCCTTCGAG TTACATTTCCCGGCCCATCTC 151 XLOC_110310 AGTGGTAGGGCAAGTCCTCT CGTGGTGGGATTCAAAGGGA 187 COL1A1, collagen type I alpha 1; COL6A1, collagen type VI, alpha 1; COL2A1, collagen type II alpha 1; DCT, dopachrome tautomerase; PDE4D, phosphodiesterase 4D cAMP‑specific. Table SII. The differentially expressed mRNAs in the ParoAF_Control group. Gene ID logFC P‑Value Symbol Description ENSG00000165480 ‑6.4838 8.32E‑12 SKA3 Spindle and kinetochore associated complex subunit 3 ENSG00000165424 ‑6.43924 0.002056 ZCCHC24 Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 24 ENSG00000182836 ‑6.20215 0.000817 PLCXD3 Phosphatidylinositol‑specific phospholipase C, X domain containing 3 ENSG00000174358 ‑5.79775 0.029093 SLC6A19 Solute carrier family 6 (neutral amino acid transporter), member 19 ENSG00000168916 ‑5.761 0.004046 ZNF608 Zinc finger protein 608 ENSG00000134343 ‑5.56371 0.01356 ANO3 Anoctamin 3 ENSG00000110400 ‑5.48194 0.004123 PVRL1 Poliovirus receptor‑related 1 (herpesvirus entry mediator C) ENSG00000124882 ‑5.45849 0.022164 EREG Epiregulin ENSG00000113448 ‑5.41752 0.000577 PDE4D Phosphodiesterase -

Supporting Table S3 for PDF Maker

Supplemental Table S3. Annotation of identified proteins. Number of Sequence Accession Number of Theoretical Subcellular Number Locus ID Gene Name Protein Name Identified Coverage Theoretical pI Protein Family NSAF Number Amino Acid MW (Da) Location of TMD Peptides (%) (O08539) Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1 O08539 BIN1_MOUSE BIN1 (Bridging integrator 1) (Amphiphysin-like protein) 3 10.5 588 64470 5 Nucleus other NONE 5.73E-05 (Amphiphysin II) (SH3-domain-containing protein 9) (O08547) Vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b (SEC22 O08547 SC22B_MOUSE SEC22B 5 30.4 214 24609 8.5 Cytoplasm other 2 0.000262 vesicle-trafficking protein-like 1) (O08553) Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 (DRP-2) O08553 DPYL2_MOUSE DPYSL2 5 19.4 572 62278 6.4 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 7.85E-05 (ULIP 2 protein) O08579 EMD_MOUSE EMD (O08579) Emerin 1 5.8 259 29436 5 Nucleus other 1 8.67E-05 (O08583) THO complex subunit 4 (Tho4) (RNA and transcription O08583 THOC4_MOUSE THOC4 export factor-binding protein 1) (REF1-I) (Ally of AML-1 1 9.8 254 26809 11.2 Nucleus NONE 2.21E-05 regulator and LEF-1) (Aly/REF) O08585 CLCA_MOUSE CLTA (O08585) Clathrin light chain A (Lca) 2 4.7 235 25557 4.5 Plasma Membrane other NONE 0.000287 (O08600) Endonuclease G, mitochondrial precursor (EC O08600 NUCG_MOUSE ENDOG 4 23.1 294 32191 9.5 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 0.000134 3.1.30.-) (Endo G) (O08638) Myosin-11 (Myosin heavy chain, smooth O08638 MYH11_MOUSE MYH11 8 6.6 1972 227026 5.5 Cytoplasm other NONE 3.13E-05 muscle isoform) (SMMHC) (O08648) Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase -

Parabiosis to Elucidate Humoral Factors in Skin Biology Casey A

RESEARCH TECHNIQUES MADE SIMPLE Research Techniques Made Simple: Parabiosis to Elucidate Humoral Factors in Skin Biology Casey A. Spencer1 and Thomas H. Leung1,2,3 Circulating factors in the blood and lymph support critical functions of living tissues. Parabiosis refers to the condition in which two entire living animals are conjoined and share a single circulatory system. This surgically created animal model was inspired by naturally occurring pairs of conjoined twins. Parabiosis experiments testing whether humoral factors from one animal affect the other have been performed for more than 150 years and have led to advances in endocrinology, neurology, musculoskeletal biology, and dermatology. The development of high-throughput genomics and proteomics approaches permitted the identification of po- tential circulating factors and rekindled scientific interest in parabiosis studies. For example, this technique may be used to assess how circulating factors may affect skin homeostasis, skin differentiation, skin aging, wound healing, and, potentially, skin cancer. Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2019) 139, 1208e1213; doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1134 CME Activity Dates: 21 May 2019 CME Accreditation and Credit Designation: This activity has Expiration Date: 20 May 2020 been planned and implemented in accordance with the Estimated Time to Complete: 1 hour accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint Planning Committee/Speaker Disclosure: All authors, plan- providership of Beaumont Health and the Society for Inves- ning committee members, CME committee members and staff tigative Dermatology. Beaumont Health is accredited by involved with this activity as content validation reviewers fi the ACCME to provide continuing medical education have no nancial relationships with commercial interests to for physicians. -

Isolating the Role of Corticosterone in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Genomic Stress Response

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.330209; this version posted October 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Isolating the role of corticosterone in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal 2 genomic stress response 3 4 By: Suzanne H. Austin1, *, Rayna Harris1, April M. Booth1, Andrew S. Lang2, Victoria S. Farrar1, 5 Jesse S. Krause1, 3, Tyler A. Hallman4, Matthew MacManes2, and Rebecca M. Calisi1 6 7 1Department of Neurobiology, Physiology, and Behavior, University of California Davis, 1 8 Shields Avenue, Davis, CA, USA, 95616 9 2 Department of Molecular, Cellular and Biomedical Sciences, The University of New 10 Hampshire, 434 Gregg Hall, Durham, NH, USA, 03824 11 3 Department of Biology, University of Nevada, Reno, 1664 N. Virginia Street, Reno, NV, USA, 12 89557-0314 13 4 Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 104 Nash Hall, Corvallis, OR 14 97331 15 16 *Current address: 17 Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, 3029 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, OR, 18 USA, 97331; Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 104 Nash Hall, 19 Corvallis, OR 97331 20 21 22 23 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.08.330209; this version posted October 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Genetically-Modified Macrophages Accelerate Myelin Repair

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.28.358705; this version posted October 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. GENETICALLY-MODIFIED MACROPHAGES ACCELERATE MYELIN REPAIR Vanja Tepavčević1,2, *, Gaelle Dufayet-Chaffaud1 ,Marie-Stephane Aigrot1, Beatrix Gillet- † † Legrand 1, Satoru Tada1, Leire Izagirre2, Nathalie Cartier1* , and Catherine Lubetzki1,3 * 1 ONE SENTENCE SUMMARY: Targeted delivery of Semaphorin 3F by genetically-modified macrophages accelerates OPC recruitment and improves myelin regeneration ABSTRACT Despite extensive progress in immunotherapies that reduce inflammation and relapse rate in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), preventing disability progression associated with cumulative neuronal/axonal loss remains an unmet therapeutic need. Complementary approaches have established that remyelination prevents degeneration of demyelinated axons. While several pro-remyelinating molecules are undergoing preclinical/early clinical testing, targeting these to disseminated MS plaques is a challenge. In this context, we hypothesized that monocyte (blood) -derived macrophages may be used to efficiently deliver repair-promoting molecules to demyelinating lesions. Here, we used transplantation of genetically-modified hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to obtain circulating monocytes that 1 1. INSERM UMR1127 Sorbonne Université, Paris Brain Institute (ICM), Paris, France. 2. Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience/University of the Basque Country, Leioa, Spain 3. AP-HP, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France * corresponding authors † senior co-authors 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.28.358705; this version posted October 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder.