Jinja Transformed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of the Colonies. Uganda 1920

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 1112. UGANDA. REPORT FOR 1920 (APRIL TO DECEMBER). (For Report for 1919-1920 see No. 1079.) LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any T3ookscller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: IMPERIAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONC-ON, W.C.2, and 28, ABINGDON STREET, LONDON, S.W.I; 37, PETER STREET, MANCHESTER; 1, ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF; 23, FORTH STREET, EDINBURGH; or from EASON & SON. LTD., 40-41, LOWER SACKVII.I-E STREET, DUBLIN. 1922. Price 9d. Net. INDEX. PREFACE I. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS II. GOVERNMENT FINANCE III. TRADE, AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRIES IV. LEGISLATION V. EDUCATION VI. CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY VII. COMMUNICATIONS.. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS' RECEIVED &0dUM£NT$ DIVISION -fTf-ViM-(Hff,>itmrtn«l,.ni ii ii in. No. 1112. Annual Report ON THE Uganda Protectorate FOR THE PERIOD 1st April to 31st December 1920.* PREFACE. 1. Geographical Description.—The territories comprising the Uganda Protectorate lie between Belgian Congo, the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and the country known until recently as German East Africa (now Tanganyika Territory). The Protectorate extends from one degree of south latitude to the northern limits of the navigable waters of the Victoria Nile at Nimule. It is flanked on the east by the natural boundaries of Lake Rudolf, the river Turkwel, Mount Elgon (14,200 ft.), and the Sio river, running into the north-eastern waters of Lake Victoria, whilst the outstanding features on the western side are the Nile Watershed, Lake Albert, the river Semliki, the Ruwenzori Range (16,794 ft.), and Lake Edward. -

Museveni Urges Elected Kyabazinga on Unity

10 NEW VISION, Monday, September 1, 2014 REGIONAL NEWS Museveni urges elected Kyabazinga on unity KAMPALA meeting a delegation of 16 Museveni said. He commended kingdom officials from Busoga the paramount chiefs upon the By Vision Reporter led by Nadiope at State House achievement and urged them Entebbe. He congratulated to unite the people of Busoga President Yoweri Museveni them upon the successful for the sake of development has urged the new Kyabazinga election of their king, saying instead of splitting them. of Busoga, William Gabula in the past, elections of a Nadiope thanked the Nadiope IV, to unite his Kyabazinga were marred by President for securing peace in people and rally them for lack of quorum. Busoga and pledged to unify development. He added that “I congratulate you upon and reconcile his people for so much time has been lost your victory. You had the the good of Busoga. Nadiope’s and yet there is much that quorum of 10 people out of 11 coronation and enthronement needs to be done. who voted for you as required has been scheduled for President Museveni meeting Nadiope (centre) at State House Entebbe. Photo by PPU The President was recently by the Busoga constitution,’’ September 13, at Bugembe. Chief prince installs rival Wambuzi as Kyabazinga JINJA death of Henry Wako Muloki a spear, shield and a drum to in September 2008, declared Wambuzi at his private palace By Charles Kakamwa that Wambuzi, Muloki’s heir, in Nakabango village, Jinja was the right person to ascend district. He explained that what The disagreement over the the throne. -

E464 Volume I1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM

E464 Volume i1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM Public Disclosure Authorized Preparedfor: UGANDA A3 NILE its POWER Richmond;UK Public Disclosure Authorized Fw~~~~I \ If~t;o ,.-, I~~~~~~~ jt .4 ,. 't' . .~ Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: t~ IN),I "%4fr - - tt ?/^ ^ ,s ENVIRONMENTAL 111teinlauloln.al IMPACT i-S(. Illf STATEME- , '. vi (aietlph,t:an,.daw,,, -\S_,,y '\ /., 'cf - , X £/XL March, 2001 - - ' Public Disclosure Authorized _, ,;' m.. .'ILE COPY I U Technical Resettlement Technical Resettlement Appendices and A e i ActionPlan ,Community ApenicsAcinPla Dlevelopment (A' Action Plan (RCDAP') The compilete Bujagali Project EIA consists of 7 documents Note: Thetransmission system documentation is,for the most part, the same as fhat submittedto ihe Ugandcn National EnvironmentalManagement Authority(NEMAI in December 2000. Detailsof the changes made to the documentation betwoon Dccomber 2000 and the presentsubmission aro avoiloblo from AESN P. Only the graphics that have been changed since December, 2000 hove new dates. FILE: DOChUME[NTC ,ART.CD I 3 fOOt'ypnIp, .asod 1!A/SJV L6'.'''''' '' '.' epurf Ut tUISWXS XillJupllD 2UI1SIXg Itb L6 ... NOJIDSaS1J I2EIof (INY SISAlVNV S2IAIlVNTIuaJ bV _ b6.sanl1A Puu O...tp.s.. ZA .6san1r^A pue SD)flSUIa1DJltJJ WemlrnIn S- (7)6. .. .--D)qqnd llH S bf 68 ..............................................................--- - -- io ---QAu ( laimpod u2Vl b,-£ 6L ...................................... -SWulaue lu;DwIa:43Spuel QSI-PUU'l Z btl' 6L .............................................----- * -* -SaULepunog QAfjP.4SlUTtUPad l SL. sUOItllpuo ltUiOUOZg-OioOS V£ ££.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A2~~~~~~~~~3V s z')J -4IOfJIrN 'Et (OAIOsOa.. Isoa0 joJxxNsU uAWom osILr) 2AX)SO> IsaIo4 TO•LWN ZU£N 9s ... suotll puoD [eOT20olla E SS '' ''''''''..........''...''................................. slotNluolqur wZ S5 ' '' '' '' ' '' '' '' - - - -- -........................- puiN Z'Z'£ j7i.. .U.13 1uu7EF ................... -

Bujagali Final Report

INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL COMPLIANCE REVIEW REPORT ON THE BUJAGALI HYDROPOWER AND INTERCONNECTION PROJECTS June 20, 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The IRM Compliance Review Panel could not have undertaken and completed this report without the generous assistance of many people in Uganda and at the African Development Bank. It wishes to express its appreciation to all of them for their cooperation and support during the compliance review of the Bujagali Hydropower and Interconnection projects. The Panel thanks the Requesters and the many individuals from civil society and the communities that it met in the Project areas and in Kampala for their assistance. It also appreciates the willingness of the representatives of the Government of Uganda and the projects’ sponsors to meet with the Panel and provide it with information during its visit to Uganda. The Panel acknowledges all the help provided by the Resident Representative of the African Development Bank in Uganda and his staff and the willing cooperation it has received from the Bank’s Management and staff in Tunis. The Panel appreciates the generous cooperation of the World Bank Inspection Panel which conducted its own review of the “UGANDA: Private Power Generation Project”. The Compliance Review Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel coordinated their field investigations of the Bujagali projects and shared consultants and technical information during this investigation in order to enhance the efficiency and cost effectiveness of each of their investigations. While this collaboration between the Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel worked to the mutual benefit of both parties, each Panel focused its compliance review on its own Bank’s policies and procedures and each Panel has made its own independent judgments about the compliance of its Management and staff with its Bank’s policies and procedures. -

Bigwala Mus Ic and Dance of the Bas Oga People

BIGWALA MUSIC AND DANCE OF THE BASOGA PEOPLE written by James Isabirye 2012 Background The Basoga are Bantu speaking people who live in southeastern Uganda. They are neighbors to the Baganda, Bagwere, Basamia, Banyoli and Banyoro people. The Basoga are primarily subsistence agricultural people. "Bigwala” is a Lusoga language term that refers to a set of five or more monotone gourd trumpets of different sizes. The music of the trumpets and the dance performed to that music are both called “Bigwala”. Five drums accompany “Bigwala” music and they include a big drum “Engoma e ne ne ”, a long drum “Omugaabe,” short drum “Endyanga”, a medium size drum “Mbidimbidi” and a small drum “Enduumi ” each of which plays a specific role in the set. Bigwala heritage is of significant palace / royal importance because of its ritualistic role during burial of kings, coronations and their anniversaries and stands as one of the main symbols of Busoga kingship. When King Henry Wako M uloki passed away on 1st September 2008, the "Bigwala" players were invited to Nakabango palace and Kaliro burial ground to perform their funeral function. 1 During the coronation of late king Henry Wako Muloki on 11th February 1995; the Bigwala players performed their ritual roles. It is important to note that Busoga kingdom like all others had been abolished in 1966 by the Ugandan republic government of Obote I and all aspects its existence were jeopardised including the Bigwala. The Kingship is the only main uniting identity which represents the Basoga, offers them opportunity to exist in a value system, focuses their initiatives to deal with development issues with in the framework of their ethnic society and connects them to their cherished past. -

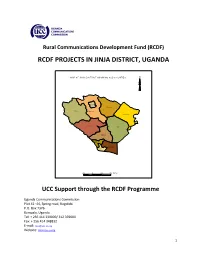

Rcdf Projects in Jinja District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN JINJA DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F JINJA DIS TR ICT S HO W ING S UB CO U NTIES N B uw enge T C B uy engo B uta gaya B uw enge Bus ed de B udon do K ak ira Mafubira Mpum udd e/ K im ak a Masese/ Ce ntral wa lukub a Div ision 20 0 20 40 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....………3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……....5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Jinja district………………l….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Jinja district………..………………….………………....…….14 10- Map of Jinja district showing sub counties………..…………………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Jinja district by sub counties……………….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Jinja District…………………………………….………..…..…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

———— “Mudo”: the Soga 'Little Red Riding Hood'

LILLIAN BUKAAYI TIBASIIMA ———— º “Mudo”: The Soga ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ABSTRACT This essay analyses the social underpinnings of the oral tale of “Mudo,” which belongs to the Aarne–Thompson tale type 333, along with a group of similar tales that resemble the action and movement of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Basic to the exposition is Adolf Bastian’s assertion of the fundamental similarity of ideas between all social groups. In the “Mudo” story and its Ugandan variants, the victim is a solitary little girl and the villain a male ogre who devises ways of eating her; the ogre is mostly successful, although in some variants the girl manages to escape. Although these tales come from a great range of cultures and different geographical locations, and the counterpart of the ogre in the European tales is a wolf in disguise, they share elements of plot, characteriza- tion, and motif, and address similar concerns. Introduction USOGA IS PART OF EAS TERN UGANDA, surrounded by water. The B Rev. Fredrick Kisuule Kaliisa1 notes: To the west is river Kiira (Nile) marking the boundary between Buganda and Busoga. To the East is river Mpologoma separating Busoga from Bukedi. To the North are river Mpologoma and Lake Kyoga, forming the boundary be- tween Busoga and Lango. To the south, is Lake Victoria (Nalubaale). It might be the result of the geographical location of Busoga that ogre stories were composed to warn the people against impending harm if they went out alone and stayed in secluded places. Nnalongo Lukude emphasizes this: Historically, Busoga was surrounded by bodies of water and forests, it was very bushy and as a result harboured many wild animals, some of which were man-eaters. -

24-Investigation Report (English)

1 Part One Introduction 2 Chapter 1 The Projects and Their Financing 1. This Report addresses questions concerning three IDA-financed projects in Uganda: namely, (1) the Power III Project, otherwise known as the Owen Falls Extension; the Supplemental Loan to the Power III Project; (2) the Power IV Project, which finances power generation Units 14 and 15, (the latter if economically viable); and (3) the Bujagali Hydropower Project.1 1.1. The Power III Project (Owen Falls Extension) 2. In the mid-1980s, soon after IDA recommenced its involvement in Uganda, a severe deterioration of power infrastructure was identified as a serious obstacle to the revival of the commodity-producing sectors of the economy. In 1988, with IDA’s assistance, the Government began work on the Power III Project. According to the Development Credit Agreement for the Project, its objectives were to: “ (a) assist the Borrower with the continued rehabilitation of the power system in Uganda; and (b) develop its hydroresources and expand the transmission and distribution system, to provide reliable, least-cost energy to Uganda's growing population.”2 The Project provided for: a) “… dam strengthening, construction of a spillway, plant capacity expansion by at least 102MW, and civil works to accommodate a plant capacity of 170MW; b) rehabilitation and expansion of transmission and distribution on the national grid; and c) provision of technical assistance services mainly to the Uganda Electricity Board (UEB) and the Ministry of Energy.” 3 IDA provided a credit of SDR 86,900,000 (about US$125 million) for this work. The projects included the installation of three units (11, 12 and 13) and provided capacity for two additional units in the future. -

Bujagali Energy Limited Project Number

BUJAGALI ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SUMMARY Project Title: Bujagali Energy Limited Project Number: P-UG-FAB-008 Country: Uganda Department: Energy Financial Solutions, Policy & Regulation Division: Energy Financial Solutions Project Category: 1 1.0 Introduction Bujagali Energy Limited (BEL) is owned by SG Bujagali Holdings Ltd (an affiliate of Sithe Global Power LLC), Jubilee Insurance Company Ltd., as well as the Africa Power Platform PCC, which is owned by CDC (the UK’s Development Finance Institution), the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFED) and IPS Kenya (“the Sponsors”). Operations and Maintenance Energy (Uganda) Limited (O&ME) operates the Hydropower project. The Bujagali Project is a 250MW hydropower facility — developed through a build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) model — on the Victoria Nile River near the town of Jinja. It reached financial close in 2007, eight years after Government of Uganda (GoU) liberalized its electricity sector in 1999. When commissioned in 2012, it did not only displace expensive emergency power generation, but also contributed towards paving the way for a handful of other smaller scale IPPs that will provide more than 200 MW of small hydro, solar, and bagasse power to the network by around 2020. However, to drive the country’s industrialization program, the GoU is actively looking for ways to reduce the country’s electricity tariffs. In this context, and based on the projected tariff profile, the Bujagali tariff is set to increase from 11.3 US cents/kWh in 2016 to 13.3 US cents/kWh in 2018 and to 14.7 US cents by 2023 due to end of a tax ‘holiday’ (accelerated depreciation) and the debt amortization — before decreasing to 7 US cents/kWh from 2024. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of January 2017

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY 2017 Issue Date: 6th February 2017 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. National Overview Tension continues to rise in the Rwenzori sub region following the re-arrest of the King (Omusinga) Charles Wesley Mumbere of the Rwenzururu Kingdom (Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu). He had been arrested in December 2016 on charges related to terrorism, aggravated robbery and attempted murder.1 These charges stemmed from attacks on police officers and police installations in the region in the last couple of months. King Mumbere was re-arrested just hours after Jinja High Court released him on bail. Prior to the re- arrest, one of the bail conditions was that he should not go to his Kingdom. The re-arrest of the King has not gone down well with some sections of his Kingdom. Area Members of the Parliament have condemned the re-arrest saying it was betrayal of the entire kingdom by the President of Uganda, and that the re-arrest was unlawful.2 However Police say King Mumbere was re-arrested because the latest investigations discovered other charges which he individually committed during the clashes in the region.3 The re-arrest of the King has the possibility of worsening the already precarious situation. In the last three years, more than three hundred (300) people have been killed, military installations attacked, houses, property and domestic livestock destroyed and many people injured in a conflict that is multidimensional. -

Are Family Planning Programs Reaching the Disadvantaged? an Equity Case Study of Uganda

POLICY Brief September 2020 Are Family Planning Programs Reaching Authors: Kaja Jurczynska, the Disadvantaged? Kevin Ward, Lyubov Teplitskaya, Shiza Farid, and Kristin Bietsch An Equity Case Study of Uganda Introduction In just over a decade, the share of married women using modern methods of contraception in Uganda nearly doubled, increasing Equity in health means that from 18 percent in 2006 to 35 percent in 2016, and to a further 37 everyone has a fair opportunity 1 percent in 2019 (UBOS and ICF, 2018; FP2020, 2020). Uganda to reach their health potential, has cemented its commitment to family planning through the regardless of wealth, education, country’s first Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan for sex, age, race or ethnic group, 2015–2020 and subsequent pledges under the Family Planning residence, disability, and other 2020 (FP2020) partnership. Among its goals, Uganda has status or social group. committed to reducing inequities, particularly for those living in rural areas, adolescents, and those facing financial hardship (Ministry of Health, 2014; FP2020, 2017). Despite this progress, Uganda has experienced challenges in Box 1. HP’s Approach for meeting its family planning commitments for 2020 and 2021, Diagnosing Inequity in including those that are equity focused. For example, unmet Family Planning Programs need is higher than desired, at one quarter of all married women compared to the goal of 10 percent by 2020. The use of modern The approach answers the “who, contraceptive methods lags behind the 2020 goal of 50 percent what, and where” of inequities in (FP2020, 2019). While inadequate funding of family planning family planning: activities remains a key barrier to progress (Wanyana et al., 2019), better directing information and services for those women who • Who is experiencing inequity? need them most could address longstanding inequities while also • What components of bolstering uptake and improving allocative efficiency. -

Kakira Outgrowers: Their Success Stories Royal Visit to Paraa Safari

Madhvani Group Magazine Volume 21 No. 1 January 2013 Madhvani Foundation receives prestigious award from H.E. President Museveni Royal visit to Paraa Safari Lodge Kakira Outgrowers: Their success stories When it comes to protecting AGRO INDUSTRY + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sugar Ltd. Excel Construction Ltd. Email:[email protected] your product and image both P.O Box 121, Jinja, Uganda P O Box 1202, Jinja Uganda Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 444000 Tel: 041 4221996/ 4505959 Fax: 041 444333/6 Fax: 043 4123150/ 041 4220482 Mara Leisure Camp E-mail: [email protected] E-mail:[email protected] P. O. Box 48995-00100 Inside and outside... Web site: www.kakirasugar.com [email protected] Nairobi, Kenya Website: www.excelconstruction.org + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sweets and Confectioneries Email:[email protected] P O Box 121, Jinja Uganda TOURISM Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 4444000 Mweya Safari Lodge Fax: 041 4444110 P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda GROUP SERVICES E-mail: kakirasweets@kakirasweets. Tel: 031 2260260/1 Muljibhai Madhvani & Co. Ltd. com Fax: 041 4340056 P O Box 54, Jinja Uganda Lodge Tel. No. 041 4340054 Tel. 042 4121218/4120511 Mwera/ Nakigalala Tea Estates Lodge Fax No. 041 4340056 Fax: 043 4123174 P O Box 6361, Kampala, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 075 2799888 Website: www.marasa.net Fax 041 4269399 Madhvani Group Projects Division E-mail: [email protected] Paraa Safari Lodge P O Box 6361 Kampala Uganda [email protected] P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda Tel: 041 4259390/4/5 [email protected] Tel: 031 2260260/1 Fax: 041 4259399 Fax: 041 4340056 E-mail: [email protected] Kajjansi Roses Ltd.