Participatory Action Research As a Methodology for the Development of Appropriate Technologies by Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COLOMBIA by George A

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF COLOMBIA By George A. Rabchevsky 1 Colombia is in the northwestern corner of South America holders of new technology, and reduces withholding taxes. and is the only South American country with coastlines on Foreign capital can be invested without limitation in all both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The majestic sectors of the economy. Andes Mountains transect the country from north to south in The Government adopted a Mining Development Plan in the western portion of the country. The lowland plains 1993 as proposed by Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones en occupy the eastern portion, with tributaries of the Amazon Geociencias, Mineria y Quimica (Ingeominas), Empresa and Orinoco Rivers. Colombiana de Carbon S.A. (Ecocarbon), and Minerales de Colombia is known worldwide for its coal, emeralds, gold, Colombia S.A. (Mineralco). The plan includes seven points nickel, and platinum. Colombia was the leading producer of for revitalizing the mineral sector, such as a new simplified kaolin and a major producer of cement, ferronickel, and system for the granting of exploration and mining licenses, natural gas in Latin America. Mineral production in provision of infrastructure in mining areas, and Colombia contributed just in excess 5% to the gross environmental control. The Government lifted its monopoly domestic product (GDP) and over 45% of total exports. Coal to sell gold, allowing anyone to purchase, sell, or export the and petroleum contributed 45% and precious stones and metal. metals contributed more than 6% to the Colombian economy. In 1994, the Colombian tax office accused petroleum companies for not paying the "war tax" established by the Government Policies and Programs 1992 tax reform. -

FLOODS 22 May 2006 the Federation’S Mission Is to Improve the Lives of Vulnerable People by Mobilizing the Power of Humanity

DREF Bulletin no. MDRCO001 COLOMBIA: FLOODS 22 May 2006 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 183 countries. In Brief This DREF Bulletin is being issued based on the situation described below reflecting the information available at this time. CHF 160,000 (USD 132,642 or EUR 103,320) was allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to respond to the needs in this operation. This operation is expected to be implemented over 3 months, and will be completed in late August 2006; a Final Report will be made available three months after the end of the operation in November 2006. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: · Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. · Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. · Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. · Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. For further information specifically related to this operation please contact: · In -

The Mineral Industry of Colombia in 2003

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF COLOMBIA By Ivette E. Torres Colombia was the fourth largest country in Latin America and new agency became responsible for assigning hydrocarbons the Caribbean, and in terms of purchasing power parity, it had areas for exploration and production; evaluating the the fourth largest economy in the region after Brazil, Argentina, hydrocarbon potential of the country; designing, promoting, and Chile. Colombia’s gross domestic product was $77.6 billion1 negotiating, and administering new exploration and production at current prices and $282 billion based on purchasing power contracts; and collecting royalties on behalf of the Government. parity. The country’s economy grew by 3.7% after modest The decree also created the Sociedad Promotora de Energía de increases of 1.6% (revised) and 1.4% (revised) in 2002 and Colombia S.A., which had as its main objective participation 2001, respectively (International Monetary Fund, 2004§2). This and investment in energy-related companies. With the creation economic growth was propelled, in part, by a significant growth of the two organizations, Ecopetrol’s name was changed to in the mining and quarrying (included hydrocarbons) and Ecopetrol S.A., and the entity, which became a public company construction sectors, which increased in real terms by 12.4% and tied to the MME, was responsible for exploring and producing 11.7%, respectively. The large contributors to the increase in from areas under contract prior to December 31, 2003, those the mining and quarrying sector were metallic minerals and coal that had been operated by Ecopetrol directly, and those to be with increases of 73% and 33%, respectively (Departamento assigned to it by ANH. -

Structural Evolution of the Northernmost Andes, Colombia

Structural Evolution of the Northernmost Andes, Colombia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 846 Prepared in coopeTation ·with the lnstituto Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico-MineTas under the auspices of the Government of Colombia and the Agency for International Development) United States DepaTtment of State Structural Evolution of the Northernmost Andes, Colombia By EARL M. IRVING GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 846 Prepared in cooperation ·with the lnstituto Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico-Min eras under the auspices of the Government of Colombia and the Agency for International Development) United States Department of State An interpretation of the geologic history of a complex mountain system UNITED STATES GOVERNlVIENT PRINTING OFFICE, vVASHINGTON 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Irving, Earl Montgomery, 1911- Structural evolution of the northernmost Andes, Columbia. (Geological Survey professional paper ; 846) Bibliography: p Includes index. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16:846 1. Geology-Colombia. 2. Geosynclines----Colombia. I. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Geologico Mineras.. II. Title. III. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 846. QE239.175 558.61 74-600149 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.30 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02553 CONTENTS Page Pasre Abstract ---------------------------------------- -

FARC – ELN – State Protection – Internal Relocation – Wealthy Families/Business Operators – Extortion 17 January 2012

Country Advice Colombia Colombia – COL39766– Granada – FARC – ELN – State protection – Internal relocation – Wealthy families/business operators – Extortion 17 January 2012 1. Deleted. 2. Please provide information relating to guerrilla groups active in Granada, Cundinamarca, both now and over the past 10 years. Limited recent information was located specifically regarding guerrilla activity in Granada, Cundinamarca. While guerrilla activity has been a long-standing feature of the region, Colombian authorities appear to have made progress in countering guerrilla activities.1 Although it is thought that rebels are seeking to retake lost ground, it is likely that they may focus on larger cities rather than regional areas.2 Information was located regarding guerrilla activity in Cundinamarca department more broadly; it should be noted that Colombia‟s capital city, Bogota, is situated within Cundinamarca department, an estimated 49 kilometres from Granada.3 According to a 2006 US diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks in August 2011, following Colombian military efforts in Cundinamarca and Bogota, “[t]he FARC [Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia] and ELN [Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional] presence has been largely eliminated – converting a military problem of national security to a police matter of public security”. The Colombian military reportedly maintained responsibility for guarding infrastructure in the region, while the police had taken over responsibility for law 1 US Department of State 2006, „Fighting Terrorism and Establishing -

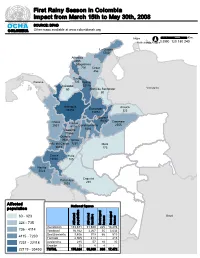

OCHA SOURCE: DPAD COLOMBIA Other Maps Available at Aruba ° Km

First Rainy Season in Colombia Impact from March 15th to May 30th, 2008 OCHA SOURCE: DPAD COLOMBIA Other maps available at www.colombiassh.org Aruba ° Km. Netherlands Antille s 0 306 0 120 180 240 La Guajira 5700 Atlántico 2465 Magdalena 700 Cesar 456 Sucre Panama 735 Bolívar Córdoba 22118 Venezuela 60 Norte de Santander 80 Antioquia Arauca Santander 35453 323 13072 Boyacá 19230 Casanare Chocó Caldas 2555 2951 4114 Cundinamarca Risaralda 6382 17666 Quindío 3925 Tolima Valle del Cauca 7230 Meta 5873 173 Cauca Huila 16680 185 Nariño 5524 Caquetá Putumayo 238 2093 Affected Ecuador National figures population n o ed i ed y ed ed at es Brazil o t t l 60 323 i r ag es es l u t i ec ec p m m f f f f es am o o o 324 735 am A p A f D h D h Inundación 153,671 31,940 225 13,476 736 4114 Vendaval 16,162 Peru 3,267 55 3,034 4115 7230 Deslizamiento 3,406 709 66 519 Tornado 2,065 413 413 7231 22118 Avalancha 285 57 10 30 Erosión 35 4 4 22119 35453 TOTAL 175,624 36,390 360 17,472 First Rainy Seasonis incurrently Colombia crossing Colombia from east to west and will worsen conditions in the upcoming days. Impact from March 15th to May 30th, 2008 1. Situation 1.2. Earthquakes According to INGEOMINAS (June 3rd, 2008), the 1.1. First rainy season past 10 notable earthquakes between May 24th and Starting on March 15th, DPAD1 began to register June 2nd occurred in central Colombia. -

Redalyc.Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV), Weeds and Thrip Vectors In

Agronomía Colombiana ISSN: 0120-9965 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Ebratt R., Everth E.; Acosta A., Rocio; Martínez B., Olga Y.; Guerrero G., Omar; Turizo A., Walther Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), weeds and thrip vectors in the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in the Andean region of Cundinamarca (Colombia) Agronomía Colombiana, vol. 31, núm. 1, enero-abril, 2013, pp. 58-67 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180328568007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative CROP PROTECTION Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), weeds and thrip vectors in the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in the Andean region of Cundinamarca (Colombia) Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), malezas y vectores de trips en el tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en la región andina de Cundinamarca (Colombia) Everth E. Ebratt R.1, Rocio Acosta A.2, Olga Y. Martínez B.3, Omar Guerrero G.4, and Walther Turizo A.5 ABSTRACT RESUMEN The presence and distribution of the TSWV, weeds and thrip La presencia y distribución de TSWV, arvenses y los trips vectors in major tomato producing areas in the Andean de- vectores en las principales zonas productoras de tomate en partment of Cundinamarca (Oriente, Sumapaz and Ubate la región andina del departamento de Cundinamarca (pro- provinces) were assessed with the DAS ELISA technique, evalu- vincias de Oriente, Sumapaz y Ubaté), se confirmó mediante ating the presence of the TSWV in tomato tissue, associated la técnica DAS ELISA, se evaluó la presencia del virus TSWV thrips and weeds. -

Characteristics of Patients with Gastric Cancer Referred to the Hospital Universitario De La Samaritana in Cundinamarca Department from 2004 to 2009

Original articles Characteristics of patients with gastric cancer referred to the Hospital Universitario de la Samaritana in Cundinamarca Department from 2004 to 2009 Julián David Martínez Marín, MD,1 Martín Alonso Garzón Olarte, MD,2 Jorge Iván Lizarazo Rodríguez, MD,2 Juan Carlos Marulanda Gómez, MD,2 Juan Carlos Molano Villa, MD,2 Mario Humberto Rey Tovar, MD,2 Natán Hormaza MD. 2 1 Associate Professor at the Universidad Nacional Abstract de Colombia. Gastroenterology Unit of the Hospital Universitario de La Samaritana, Bogotá D.C. This is a descriptive observational study of patients upon whom esophagogastroduodenoscopies had been Colombia performed at the hospital Universitario de La Samaritana from 2004 to 2009 and who had been diagnosed 2 Gastroenterology Unit of the Hospital Universitario de histologically with Gastric Cancer (GC). 259 cases, 153 men and 106 women, with average ages of 66 years La Samaritana, Bogotá D.C. Colombia were included. A very high proportion of patients (40%) who had sought medical assistance because of di- ......................................... gestive hemorrhaging were ultimately diagnosed with GC. 97% of these cases had advanced tumors with Received: 16-11-10 Bormann levels III and IV being the most common (72% and 16% respectively). A large percentage of patients Accepted: 30-11-10 (53%) had diffuse intestinal adenocarcinomas. Proximal locations of these tumors in the cardia, fundus, cor- pus) predominated (56.4%) especially among male patients (65%). The majority of these patients (69.4%) came from regions of the department of Cundinamarca located more than 2,000 meters above sea level. Early detection programs for GC need to be established in regions of high incidence. -

Georreferenciación De Las Termales Con Alternativas De Desarrollo Para El Turismo De Bienestar En La Región Cundinamarca

Perspectiva Geográfica ISSN: 0123-3769 Vol. 20 No. 1 de 2015 Enero - Junio pp. 203-224 Georreferenciación de las termales con alternativas de desarrollo para el Turismo de Bienestar en la región Cundinamarca Thermal Georeferencing with Development Alternative for Wellness Tourism in Cundinamarca Region Saudy Giovanna Niño Bernal1 Sonia Duarte Bajaña2 Para citar este artículo, utilice el nombre completo así: Niño, S. G. & Duarte, S. (2015). Georreferenciación de las termales con alternativas de desarrollo para el Turismo de Bienestar en la región Cundinamarca. Perspectiva Geográfica, 20(1), 203- 224. Resumen Este artículo muestra el resultado de la georreferenciación de las termales con alternativas de desarrollo para Turismo de Bienestar, presentes en el departamento de Cundinamarca. Propone evidenciar y categorizar las potencialidades que tendrá la región, acorde con la diversidad hidrológica, natural y cultural que hacen, de este territorio, un lugar con amplias apuestas productivas. Además, se pretende visibilizar dichos recursos, al reconocer que Colombia busca posicionarse como un destino de talla mundial en Turismo de Bienestar. Es así como, a manera de producto, se genera un mapa que evidencia la ubicación de las termales con potencial turístico, resultado del 1 Administradora Turística y Hotelera de la Fundación Universitaria los Libertadores, Bogotá (Colombia), Joven Investigadora cofinanciada por Colciencias en el marco del proyecto de Investigación, denominado: Alternativas de Desarrollo de Turismo de Bienestar no Visibles en la Región Bogotá, Cundinamarca. [email protected] 2 Magíster en Investigación en Problemas Sociales Contemporáneos de la Fundación Universidad Central y Trabajadora Social de la Fundación Universitaria Monserrate, Bogotá, Colombia, [email protected] análisis que permitió determinar las características y elementos considerados como alternativa de desarrollo para esta región. -

Pre-Feasibility Study for Methane Drainage and Utilization at the Casa Blanca Coal Mine, Cundinamarca Department, Colombia

U.S. EPA Coalbed Methane OUTREACH ffi0.$RA ',1 Pre-Feasibility Study for Methane Drainage and Utilization at the Casa Blanca Coal Mine, Cundinamarca Department, Colombia U.S. Environmental Protection Agency September 2019 Pre-Feasibility Study for Methane Drainage and Utilization at the Casa Blanca Mine Cundinamarca Department Colombia U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC USA EPA 430-R-19-014 September 2019 Disclaimer This publication was developed at the request of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), in support of the Global Methane Initiative (GMI). In collaboration with the Coalbed Methane Outreach Program (CMOP), Advanced Resources International, Inc. (ARI) authored this report under RTI International contract EP-BPA-18-H-0010. Information included in the report is based on data obtained from the coal mine partner, UniMinas S.A.S (Casa Blanca Mine), a subsidiary of C.I. Milpa S.A. Acknowledgements This report was prepared for the USEPA. This analysis uses publicly available information in combination with information obtained through direct contact with mine personnel, equipment vendors, and project developers. USEPA does not: a) make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained in this report, or that the use of any apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe upon privately owned rights; b) assume any liability with respect to the use of, or damages resulting from the use of, any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report; nor c) imply endorsement of any technology supplier, product, or process mentioned in this report. -

USAID/BHA) Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, San José, Costa Rica

AUGUST 2020 USAID’S BUREAU FOR HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (USAID/BHA) REGIONAL OFFICE FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN, SAN JOSÉ, COSTA RICA USAID/BHA Supports Urgent COVID-19 Response Needs in LAC Since the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic began impacting Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), the USAID/BHA team of regional humanitarian experts has worked closely with national and local governments to identify the most critical needs and provide assistance to bolster response efforts. In Ecuador’s severely affected Guayas Province, USAID/BHA responded to a request for technical assistance from Mayor of Guayaquil city Cynthia Viteri. On April 15, through the Regional Disaster Assistance Program (RDAP), USAID/BHA activated a seven-person team of experts— comprising an Ecuador-based disaster risk management specialist (DRMS) and six surge capacity consultants—in Guayaquil to support local authorities with COVID-19 crisis response. The team assisted with information management, incident command system (ICS), psychosocial support, and biosecurity and helped create a crisis room at the Guayaquil’s Directorate of Risk Management. The RDAP program has more than 400 on-call local surge capacity consultants based in 27 LAC countries who can be quickly activated to expand USAID/BHA’s regional core team capabilities. RDAP surge USAID/BHA provided hygiene kits to vulnerable households in the municipalities of Herrera, capacity consultants are highly qualified professionals with expertise in Los Santos, and Tablas in Panama. Photo by Manuel Santana, USAID/BHA diverse areas and familiarity with local languages and customs. They can be activated as required to liaise with the host government’s response facilitate response decisions, create daily infographics, and conduct a authorities, assist with local response efforts, or conduct damage and psychosocial care program for the emergency operations center (EOC) and needs assessments. -

DLA Piper Martínez Beltrán Infrastructure and Projects Pipeline General Overview

DLA Piper Martínez Beltrán Infrastructure and Projects Pipeline General overview www.dlapipermb.com 2 Projects in Colombia ANTIOQUIA BOYACÁ CESAR HUILA QUINDÍO TOLIMA ATLÁNTICO CALDAS CÓRDOBA MAGDALENA SANTANDER VALLE DEL CAUCA BOLIVAR CAUCA CUNDINAMARCA NARIÑO SUCRE www.dlapipermb.com 3 Colombia is your bet Política Nacional de Logística Plan Maestro de Plan Maestro Transporte Ferroviario Enabling Policies Accesos Urbanos Plan Maestro Fluvial Plan Aeronáutico Estratégico www.dlapipermb.com 4 Colombia is your bet The GDP per capita (PPP) in Colombia (2019) has doubled in the last 15 years As a member of OECD, More than 700 multinational Colombia will promote more companies have launched efficient transparent investment programs in institutions, and trade Colombia in the latest years, facilitation, which will allow which shows foreign investor Foreign direct investment improvement and strength in confidence (FDI) in Colombia reached its the key sectors to recover the highest number in 2019 with economy after COVID-19 US $14,493 million, registering an increase of 25.6% compared to the figures of 2018, according to Colombia was officially The Colombian economy is Colombian central bank. acknowledged in the World the fastest growing in Latin Economic Forum as the America. The country's GDP fourth most competitive grew 3.3% in 2019 country of Latin America in 2019 Colombia has access to 60 countries through free trade agreements and to 114 free zones Colombia is the Latin American country with the greatest progress towards energy transition,