Goodyear Family History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apartment Buildings in New Haven, 1890-1930

The Creation of Urban Homes: Apartment Buildings in New Haven, 1890-1930 Emily Liu For Professor Robert Ellickson Urban Legal History Fall 2006 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Defining and finding apartments ............................................................................................ 4 A. Terminology: “Apartments” ............................................................................................... 4 B. Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 9 III. Demand ............................................................................................................................. 11 A. Population: rise and fall .................................................................................................... 11 B. Small-scale alternatives to apartments .............................................................................. 14 C. Low-end alternatives to apartments: tenements ................................................................ 17 D. Student demand: the effect of Yale ................................................................................... 18 E. Streetcars ........................................................................................................................... 21 IV. Cultural acceptance and resistance .................................................................................. -

Street Sweeping

A A A Low Graphics Sitemap (/sitemap.htm) Select Language Powered by Maps (/gov/maps.htm) Emergency Info (/gov/depts/emergency_info/default.htm) Forms (/cityservices/forms.htm) (/default.htm) Street Sweeping Street Sweeping Season 2021 NEW >>Street Sweeping Calendar April- November 2021 (https://www.newhavenct.gov/civica/filebank/blobdload.asp?t=36105.04&BlobID=39514) Click here to see if your street/address was changed. (https://newhavenct.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html? id=1860b2be72814e1faeb12d59560907db) The annual program is designed to remove the heavy accumulation of salt, sand, litter and leaves that has collected over the winter months and to help keep New Haven’s 226 miles of streets clean. Department of Public Works annual street sweeping program operates April 1 – November 30 The annual program is designed to remove the heavy accumulation of salt, sand, litter and leaves that has collected over the winter months as well as help keep New Haven’s miles of streets clean. There are 14 Street Sweeping Routes in the City. Several of the Routes have had streets added or subtracted in this 2021 season ensuring productive and efficient citywide sweeping. Routes that have been impacted* are starred below: ROUTE # Neighborhoods Frequency - Monthly 1 Amity/West Rock First Monday & Wednesday 2 Beaver Hills Third Monday & Tuesday 3 * Newhallville/Prospect First Tuesday & Wednesday 4 * East Rock Second Monday & Tuesday 5* Cedar Hill/ Fair Haven Second Thursday & Friday 6 Fair Haven Heights/Foxon Third & Fourth Friday 7 Fair Haven -

Quinnipiac Ridge

'REEN-AP&RONT FINAL 0$&PDF0- A B C D E F G H I J %#/./-)#¬$%6%,/0-%.4 0ARK¬3TATION 5¬1UINNIPIAC¬2IDGE¬.ATURE¬0RESERVE¬;*= :¬#ASA¬,INDA ¬(ILL¬;&=¬ 0LACE¬TO¬GET¬INFORMATION¬ABOUT¬PARKS ¬PROGRAMS ¬LOCAL¬FLORA¬AND¬FAUNA ¬AND¬TOURS /N¬1UINNIPIAC¬!VE¬NORTH¬OF¬2TE¬ ¬ENTRANCE¬IS¬BETWEEN¬¬AND¬¬ ¬3YLVAN¬!VE¬ 1UINNIPIAC¬!VE :¬#ASA¬/NTONAL ¬(ILL¬;&=¬ &ARMERS¬-ARKET ,¬%DGEWOOD¬2ANGER¬3TATION¬;&= ¬3YLVAN¬!VE¬ 3ELL¬REGIONALLY¬AND¬ORGANICALLY¬GROWN¬PRODUCE¬3OME¬ALSO¬SELL¬FLOWERS ¬HAND¬ ,OCATED¬INSIDE¬%DGEWOOD¬0ARK¬NEAR¬THE¬CORNER¬OF¬%DGEWOOD¬!VE¬AND¬%LLA¬ 5¬(EMINGWAY¬#REEK¬.ATURE¬0RESERVE¬;*= :¬#EDAR¬(ILL¬!PARTMENTS ¬%AST¬2OCK¬;)=¬ CRAFTED¬ITEMS ¬BAKED¬GOODS ¬WINE ¬WOOL ¬EVEN¬REGIONAL¬COOKBOOKS¬3MALL¬FAMILY¬ 4¬'RASSO¬"LVD ¬THE¬2ANGER¬3TATION¬HOLDS¬A¬GREAT¬COLLECTION¬OF¬LOCAL¬ /N¬EAST¬SIDE¬OF¬1UINNIPIAC¬!VE¬IMMEDIATELY¬NORTH¬OF¬RAILROAD¬UNDERPASS ¬3TATE¬3T FARMS¬ARE¬KEPT¬GOING¬AND¬THE¬COUNTRYSIDE¬REMAINS¬GREEN¬ r AMPHIBIANS¬AND¬REPTILES¬ :¬#HAPELSEED ¬$WIGHT¬¬7EST¬2IVER¬;&=¬ D e p 5¬-ORRIS¬#REEK¬.ATURE¬0RESERVE¬;)= ¬#HAPEL¬3T B r r o UG o h !¬¬#ITY¬&ARMERSg¬-ARKET¬7OOSTER¬3QUARE¬;(= o 1 d 1 ,¬,IGHTHOUSE¬0OINT¬0ARK¬2ANGER¬3TATION¬;(= /N¬-EADOW¬6IEW¬3T¬NEAR¬,IGHTHOUSE¬0OINT :¬#ONSTANCE¬"AKER¬-OTLEY ¬.EWHALLVILLE¬;'= T R k s (',7,21 t 2USSO¬0ARK ¬CORNER¬OF¬#HAPEL¬AND¬$E0ALMA¬/PEN¬3ATURDAYS¬FROM¬ i Z4 d ¬,IGHTHOUSE¬2D¬4OUCH¬TANK¬AND¬COASTAL¬ECOLOGY¬PROGRAMS¬4OURS¬OF¬THE¬ ¬3HERMAN¬!VE¬ o e m AM PM ¬-AY¬THROUGH¬$ECEMBER¬¬7)#¬¬FOOD¬STAMPS¬ACCEPTED l LIGHTHOUSE ¬&ORT¬.ATHAN¬(ALE ¬AND¬THE¬CAROUSEL¬AVAILABLE¬ :¬#RAWFORD¬-ANOR ¬$WIGHT¬;'=¬ i 3TAR GAZING¬3ITE -

Chapter V: Transportation

Transportation CHAPTER V: TRANSPORTATION A. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Located at the junction of Interstate 91 and Interstate 95, as well as a key access point to the Northeast Corridor rail line, New Haven is the highway and rail gateway to New England. It is the largest seaport in the state and the region and also the first city in Connecticut to have joined the national complete streets movement in 2008 by adopting the City’s Complete Streets Design Manual, balancing the needs of all roadway users including pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorists. Journey to Work Data For a U.S. city of its size, New Haven has substantial share (45 Aerial view of New Haven seaport: largest in the state and the region. percent) of commuters who use a form of transportation other than driving alone. Approximately 15 percent of all commuters travel via carpool, close to 14 percent walk to work, while over 11 percent use a form of public transportation. Of the 10 largest cities in New England, only Boston has a higher percentage of residents who travel to work via non-motorized transportation. Also, out of this same group of cities, New Haven ranked highest in the percentage of people who walked to work. New Haven Vision 2025 V-1 Transportation Vehicular Circulation There are 255 miles of roadway in the city, ranging from Interstate highways to purely local residential streets. Of these roadways, 88 percent are locally-maintained public roads and 12 percent are state-maintained roads and highways. There are 43 locally- maintained bridges in the city. -

Past to Present the Newsletter of the New Haven Museum

Past to Present The newsletter of The New Haven Museum Spring 2010 Hopkins School to be Awarded Museum’s Seal of the City By Steve Gurney hree hundred fifty years ago, on the public square near what is now the intersection of Elm and Temple Streets, stood a simple one-room log cabin adorned with a large fieldstone fireplace. The square served many T purposes and within a stone’s throw of this modest structure was the town grave- yard and the local jail. Inside this small cabin, on hard oak benches, sat six or eight boys as young as eight years old, their Bibles on their laps. Throughout the day each was called upon to recite aloud a Latin or Greek passage supposed to have been memorized by candle or firelight the evening before. This was Hop- kins’s first schoolhouse; these were its first students; this was their curriculum. One can only marvel at the fierce determination required of a Puritan foremother on winter mornings as she pried a sleep-bound boy out of a warm bed in time to trudge to an unheated schoolroom with daylight still an hour or more away. One can assume she did not always succeed. Six days a week, fifty-two weeks of the year, from six in the morning until four or five in the afternoon, a few young scholars labored at their lessons in the dim light. All could hear the ongoing burials of departed Christians in the General Information nearby graveyard, the wails of convicted sinners in the jail, the grunting of hogs Museum & Library and the barking of dogs rooting among the graves. -

The Livable City Initiative ~ Data Analysis Report T E"' Haven Fire Oeparl1116 ~

r The Livable City Initiative ~ Data Analysis report t e"' Haven Fire Oeparl1116 ~ Febru..a:ry 28, 199'7 ~ 1- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface 2 Fact Sheet 3 Fact Sheet Comparison 4 Building Condition Status 5 Blighted Structure Chart 6 Vacant Building Map 7 LCI Neighborhood District Substation 8 District Property Graphs (2) 9 - 10 Target Neighborhoods 11 Demolition/Proposed Demolition 12 - 24 Fire Destroys/Create Vacant Buildings 25 - 26 Property Usting By Ward 27 - 89 2 PREFACE Data collection from the second phase of the Fire Department vacant building inspection program this past fall indicates 362 new properties have been added to the building inventory list. On the other side of the ledger 141 previous listed properties have been removed from the list. Forty-five of them have been demolished and ninety-six previous vacant structures are now occupied, some with new owners. The Fire Department has identified an additional 81 blighted structures, separate from the vacant building inventory. These buildings are partially occupied and boarded up. These structures will at some point slip into the "vacant" stage if pro-active steps are not successful. This report reflects information for the period November 1, 1996 through February 28, 1997. Edward F. Flynn, Jr. Battalion Chief Project Leader February 28, 1997 3 L· ·3 Dep'the 1\table City l11it1 ti"". ce artlhent of Fire Sef"l Fact Sheet Demolition 11/1/96 - 2/28/97 50 Demolition Order Sent Pending 62 Additional Proposed Demolitions 1 04 Fires In Properties (Before/After Vacant) 111 Properties Sold (Commercial Record) 1 03 7/ 1/ 96 - 2/ 28/ 97 Properties With Rehab Intentions 38 Properties Identified "For Sale" 3 7 Foreclosure (Commercial Record) 9 Type of Property 1 Family (411 Code) 288 2 Family ( 414 Code) 419 3/6 Family (422 Code) 307 Business (591 Code) 117 Other (Code 490) 63 4 Category Oct. -

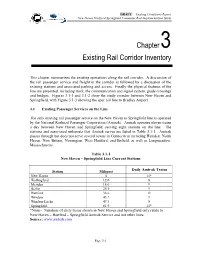

Chapter3 Existing Rail Corridor Inventory

DRAFT Existing Conditions Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study Chapter 3 Existing Rail Corridor Inventory This chapter summarizes the existing operations along the rail corridor. A discussion of the rail passenger service and freight in the corridor is followed by a discussion of the existing stations and associated parking and access. Finally the physical features of the line are presented, including track, the communication and signal system, grade crossings and bridges. Figures 3.1-1 and 3.1-2 show the study corridor between New Haven and Springfield, with Figure 3.1-3 showing the spur rail line to Bradley Airport. 3.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing rail passenger service on the New Haven to Springfield line is operated by the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak). Amtrak operates eleven trains a day between New Haven and Springfield, serving eight stations on the line. The stations and associated mileposts that Amtrak serves are listed in Table 3.1-1. Amtrak passes through but does not serve several towns in Connecticut including Hamden, North Haven, New Britain, Newington, West Hartford, and Enfield, as well as Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Table 3.1-1 New Haven – Springfield Line Current Stations Daily Amtrak Trains Station Milepost New Haven 0 11* Wallingford 12.6 8 Meriden 18.6 9 Berlin 25.9 9 Hartford 36.6 11 Windsor 43.1 9 Windsor Locks 47.3 9 Springfield 61.9 11* *Note-- Numbers of daily trains shown in New Haven and Springfield only relate to New Haven – Hartford – Springfield Amtrak Service and not other lines. -

Francis Miller, Conservator Professional Associate of Aic Since 1999 Principal, Conservart Llc

Conserve ARTLLC ANALYSIS – RESEARCH – TREATMENT FRANCIS MILLER, CONSERVATOR PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATE OF AIC SINCE 1999 PRINCIPAL, CONSERVART LLC EXPERIENCE ConservArt, LLC, 1999-Present Sculpture Conservator Francis Miller founded ConservArt LLC in 1999 to provide professional conservation treatments that uphold the conservation standards and ethics as outlined by the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. ConservArt LLC provides full conservation services for historic Colonial Cemeteries, as well as, contemporary, modern and historic sculpture, monuments, fountains and architectural objects. -Collections Consultation -Surveys -Condition Assessments -Treatment Guidelines -Analysis -Testing -Metals Conservation -Stone Conservation -Plaster Conservation -Ceramics Conservation -Site Review -Rigging and Setting -Documentation Conservation Technical Associates, LLC (Formerly Fine Objects Conservation) 1995-1999 Assistant Conservator Examined and conserved notable bronze, copper, steel, stone and terra cotta sculptures and fountains. In addition to outdoor artworks, museum objects and sculpture were also treated, including: 20th century plaster, bronze and stone sculptures, and the West Wall of the Tomb of Kapura, an Ancient Egyptian wall relief and false door complex constructed of carved and painted limestone. -Managed all aspects of large scale projects from coordinating research, acquiring materials, to managing staff and subcontractors -Removed bronze corrosion products using water jet systems and the JOS vortex -

X. APPENDIX B – Profile of City of New Haven

X. APPENDIX B – Profile of City of New Haven Welcome to New Haven! Strategically situated in south central Connecticut, New Haven is the gateway to New England, a small city which serves as a major transportation and economic hub between New York and Boston. Justly known as the cultural capital of Connecticut, New Haven is a major center for culture and entertainment, as well as business activity, world‐class research and education. As the home to Yale University and three other colleges and universities, New Haven has long been hub of academic training, scholarship and research. Anchored by the presence of Yale University and numerous state and federal agencies, New Haven is a major center for professional services, in particular architecture and law. And drawing on a spirit of Yankee ingenuity that dates to Eli Whitney, New Haven continues to be a significant manufacturing center; the city is home to high‐tech fabrics company Uretek, Inc., Assa Abloy, makers of high tech door security systems, and a vibrant food manufacturing sector. In 2009, surgical products manufacturer Covidien announced its headquarters and 400 Executive and support positions would relocate to New Haven’s Long Wharf. In 2013, Alexion Pharmaceuticals announced its plans to construct a 500,000sf global headquarters for its growing biotech company which will open in 2015. More importantly, the City of New Haven and its partners are investing for the future and despite the worst recession of the post‐World War ii era, New Haven is thriving and is in the midst of one of the strongest periods of business growth in decades. -

GNHWPCA EJPPP Wet Weather Nitrogen Project Submission

Environmental Justice Public Participation Plan OP R ! "O! P"%%%& &' ' O P Part I: Proposed Applicant Information 1. APPLICANT INFORMATION Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority 260 East Street New Haven CT 06511 203-466-5280 321 Tom Sgroi [email protected] R ✔ 2. WILL YOUR PERMIT APPLICATION INVOLVE: ✔ 3. FACILITY NAME AND LOCATION East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility & Pre-Treatment Sta. 345 East Shore Parkway (See Attached) New Haven CT 06512 052 950 400, 600, 800 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements R A. Identify Time and Place of Informal Public Meeting date, time and placeR June 21, 2012 New Haven Sound School Regional Vocational Aquaculture Center, 60 South Water St., New Haven, CT 06519 6:30pm ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * ( ))) & B. Identify Communication Methods By Which to Publicize the Public Meeting New Haven Register and La Voz June 11, 2012 (NHR), June 8, 2012 (La Voz) +, - % ) . / & 0 ( 123+$!$+"3$$ # 3 "3 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements (continued) ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ R Part III: Measures to Facilitate Meaningful Public Participation -

April 2021 Street Sweeping

April 2021 Street Sweeping Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 Route 8 - Wooster Good Friday Square No Sweeping 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Route 3 - Newhallville Route 11 - Westville Route 3 - Newhallville Prospect Route 5— Cedar Hill/ Route 5— Cedar Hill/ Prospect Fair Haven Fair Haven Route 1 - Amity/West Route 1—Amity/West Rock Route 11 - Westville Rock 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Route 6 - Fair Haven Route 4 - East Rock Route 4 - East Rock OPEN Route 12 - West Heights/Foxon River/ Hill (North) Route 7— Fair Haven Heights /Annex 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Route 13 - Hill (South) Route 6 - Fair Ha- Route 2 - Beaver Route 2 - Beaver Hills Route 12 - West River/ City Point ven Heights/Foxon Hills Hill (North) Route 14 - East Shore Cove Route 7— Fair Haven Heights /Annex 25 26 27 28 29 30 Route 10 - Edgewood Route 10 - Edgewood / Route 13 - Hill (South) Dwight Dwight City Point OPEN OPEN Route 14 - East Shore/ Cove May 2021 Street Sweeping Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 22 33 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 8 8 Route 8 - Wooster Route 11 11 - -Westville Westville RouteRoute 3 - 3 Newhallville/ - Newhallville Route Route 3 - Newhallville/3 - Newhallville Route 8 - Wooster Route 8Route - Wooster 8 - Wooster Prospect/GroveProspect Prospect/GroveProspect SquareSquare to Blatchley SquareSquare to Blatchley Ave Route 1—Amity/West Ave Rock Route 11 Westville Route 1 - Amity/West 99 1010 11 11 12 12 13 13 14 14 15 15 RouteRoute 4 - EastEast Rock/ Rock RouteRoute 4 - 4 East - East Rock/ Rock Route - OPEN RouteRoute 8 - Wooster 5— Cedar Hill/Route 5Route - Fair 5 Haven - Cedar Hill/ Cedar Hill Cedar Hill SquareFair to HavenBlatchley fromFair Blatchley Haven Ave. -

CTP Report5 Rfs.Pdf

Contents Letter from Mayor Toni Harp Letter from Dr. Martha Okafor, Community Services Administrator Introduction 1 Why New Haven needs an equitable CTP 4 What will the New Haven CTP do? 7 Crosscutting themes 8 How the CTP will achieve equity 9 The CTP theory of change 13 How the CTP will be used by the Mayor and community 15 CTP Sectors, Strategy Roadmaps 16 How to read the CTP roadmaps 17 Job Creation and Workforce Development 18 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Access to Jobs Strategy roadmap: Basic Skills and Readiness Economic Activity and Private Investment 22 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Economic Competitiveness Strategy roadmap: Revitalized Neighborhoods Strategy roadmap: Local Jobs and Businesses Strategy roadmap: Tech Companies Early Childhood 28 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Access to Early Childhood Care Strategy roadmap: Quality Early Childhood Care Strategy roadmap: Families and Caregivers Education and Positive Youth Development 33 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Student Achievement Strategy roadmap: College and Career Strategy roadmap: Caring Adults Adult Literacy and Life Skills 38 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Adult Literacy Strategy roadmap: Life Skills Community Health, Mental Health, and Wellness 42 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Asthma Strategy roadmap: Food Security Strategy roadmap: Smoking Strategy roadmap: Mental Health Community Cohesion and Safety 48 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Connect Communities Strategy roadmap: Fight Crime Housing and Physical Environment 52 Vision & 2020 Targets Strategy roadmap: Quality, Affordable Housing Strategy roadmap: Homelessness Strategy roadmap: Physical Environment Implementing the CTP 57 Where implementation will be focused 58 What implementation will look like 59 How implementation will be managed 60 Expectations and challenges 62 Notes and References 63 Acknowledgments and Credits 66 FLnedca Cftii p (.Yurc[ New He\;er,.