Triennial City: Localising Asian Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

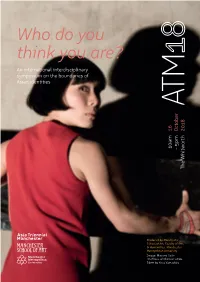

Who Do You Think You Are? an International Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Boundaries of Asian Identities ATM 16 October 2018 10Am - 5Pm the Whitworth

Who do you think you are? An international interdisciplinary symposium on the boundaries of Asian identities ATM 16 October 2018 10am - 5pm The Whitworth Produced by Manchester School of Art, Faculty of Arts & Humanities, Manchester Metropolitan University Image: Masumi Saito ‘In Praise of Shadow’ 2016. Taken by Koya Yamashiro Sixteen Days Fifteen Venues HOME Bury Art Museum MMU Special Portico Library Tony Wilson Place & Sculpture Collections 57 Mosley St Manchester Centre All Saints Library Manchester M15 4FN Moss St, Bury Manchester M2 3HY BL9 0DR M15 6BH Manchester Craft Partisan Collective and Design Centre Manchester The Whitworth 19 Cheetham 17 Oak St Art Gallery Oxford Rd Hill Rd Manchester Mosley St Manchester Manchester M4 5JD Manchester M15 6ER M4 4FY M2 3JL Manchester Manchester The Manchester Cathedral The Holden Museum Contemporary Victoria St Gallery Oxford Rd Manchester Manchester Manchester Manchester Central M3 1SX School of Art M13 9PL M2 3GX Manchester Castlefield Gallery Metropolitan Alexandria Library 2 Hewitt St University, 247 Wilmslow Rd Manchester Grosvenor Manchester M15 4GB Building M14 5LW Cavendish St Gallery Oldham Manchester 35 Greaves St M15 6BR Oldham OL1 1TJ Asia Triennial Manchester is supported by @triennialmcr #ATM18 Arts Council England and project partners: www.asiatriennialmanchester.com Who do you think you are? The Whitworth Gallery As one of the many performative 16th October 2018, 10am – 5pm reiterations of this year’s Asia Triennial, the symposium will centre on visual An international interdisciplinary -

The Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns

‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns A Roberts PhD 2016 ‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns Amber Roberts o 2016 Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 21 01 Literature Review 53 02 Research Methods 81 Region’ 119 155 181 215 245 275 298 1 Acknowledgements 2 3 Abstract ‘What is the urban image of the north- western post-industrial town?’ 4 00 Introduction This research focuses on the urban image of North West English historic cultural images, the built environment and the growing the towns in art, urban planning and the built environment throughout case of Stockport. Tesis Introduction 5 urban development that has become a central concern in the towns. 6 the plans also engage with the past through their strategies towards interest in urban image has led to a visual approach that interrogates This allows a more nuanced understanding of the wider disseminated image of the towns. This focuses on the represented image of the and the wider rural areas of the Lancashire Plain and the Pennines. Tesis Introduction 7 restructuring the town in successive phases and reimagining its future 8 development of urban image now that the towns have lost their Tesis Introduction 9 Figure 0.1, showing the M60 passing the start of the River Mersey at Stockport, image author’s own, May 2013. 10 of towns in the North West. These towns have been in a state of utopianism. persistent cultural images of the North which the towns seek to is also something which is missing from the growing literature on Tesis Introduction 11 to compare the homogenous cultural image to the built environment models to follow. -

Anya Gallaccio

Anya Gallaccio 1963 Born in Paisley, Scotland Lives and works in London, UK Education 1985-1988 Goldsmiths’ College, University of London, UK 1984-1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, UK Residencies and awards 2004 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sansalitos, California, US 2003 Nominee for the Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London, UK 2002 1871 Fellowship, Rothermere American Institute, Oxford, UK San Francisco Art Institute, California, US 1999 Paul Hamlyn Award for Visual Artists, Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award, London, UK 1999 Kanazawa College of Art, JP 1998 Sargeant Fellowship, The British School at Rome, IT 1997 Jan-March Art Pace, International Artist-In-Residence Programme, Foundation for Contemporary Art, San Antonio Texas, US Solo Exhibitions 2015 Lehmann Maupin, New York, US 2014 Stroke, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK SNAP, Art at the Aldeburgh Festival, Suffolk, UK Blum&Poe, Los Angeles, US 2013 This much is true, Artpace, San Antonio, Texas, US Creation/destruction, The Holden Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Red on Green, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK 2011 Highway, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL Where is Where it’s at, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland including the Dick Institiute, the Baird Institute and the Doon Valley Museum, Kilmarnock, UK 2009 Inaugural Exhibition, Blum & Poe Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, US Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, US 2008 Comfort and Conversation, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL That Open Space Within, Camden Arts Center, London, UK Kinsale -

Updated List of Organisations Attending DCDC15

Updated list of organisations attending DCDC15 Aberystwyth University Parliamentary Archives Adam Matthew PEEL Interactive AHRC/Roehampton University Penarth Library Alexander Street Press People's History Museum Alfred Gillett Trust (C&J Clark Ltd.) Peterborough Archives Anglesey Museums and Archives Service Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford Archives+ Preservation Matters Ltd Arts Council England Public Catalogue Foundation Auckland Museum Pyjamarama Axiell Queen Mary University of London Barnsley Arts, Museums and Archives Rachel Mulhearn Associates Ltd BBC Rambert Dance Company Belinda Dixon Media Ltd Roehampton University Birmingham City University Royal Air Force Museum Blackpool Council Royal Armouries Blackpool Library Service Royal College of Nursing Bletchley Park Trust Royal College of Physicians Bodleian Libraries Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow Bolton Museum Service Royal College of Surgeons of England Brighton College Archive Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments for Scotland British Council Royal Shakespeare Company British Library RSA British Museum Salford Business School Brunel University London Scottish Council on Archives Bruynzeel Storage Systems Ltd Senate House Library Cambridge Archive Editions Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Cambridge University Press Share Academy Cardiff University Shropshire Archives CCS Content Conversion Specialists GmbH Shropshire Archives Cengage Learning SOAS, University of London Central Saint Martins Society of Antiquaries of London Cheshire Archives -

The Democratic Image Online Projects Exhibitions Workshops Commissions Events 2 About Look 07

THE DEMOCRATIC IMAGE ONLINE PROJECTS EXHIBITIONS WORKSHOPS COMMISSIONS EVENTS 2 ABOUT LOOK 07 LOOK 07 WAS CONCEIVED BY REDEYE AND IS A PROGRAMME OF ACTIVITIES CONCERNED WITH THE REVOLUTION IN PHOTOGRAPHY. AS CAMERA OWNERSHIP IS SKYROCKETING WORLDWIDE, LOOK 07 DESCRIBES WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING WITH THIS NEW LANGUAGE; WHO’S MAKING THE MOST INTERESTING PICTURES NOW; WHO’S LOOKING AT THEM; HOW THE PUBLIC IS USING PHOTOGRAPHY AS A NEW MEANS OF EXPRESSION AND THE PLACE OF THE PROFESSIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER IN ALL THIS. LOOK 07 IS… A SYMPOSIUM WORKSHOPS The Democratic Image Symposium investigates the Look 07 brings together photographers, artists and revolution in photography with some of the world’s non-professionals for exciting projects that will be top speakers on the subject. exhibited in galleries and online. ONLINE WORK COMMISSIONS Look 07’s online gallery, Flickr gallery and blog New work commissioned from a broad range of keep the conversation going. photographers and artists will make its mark upon the city. It will also lead to an open competition. EXHIBITIONS A large number of new, lens-based exhibitions will EVENTS span Greater Manchester, many tying in with the An engaging mix of gallery talks and special symposium’s theme of The Democratic Image. events celebrate different aspects of photography. WHO’S SUPPORTING LOOK 07? Look 07 gratefully acknowledges the support of the We would also like to thank our media partners, Arts Council of England, the Association of Greater The Associated Press and Metro newspaper, and Manchester Authorities, Manchester City Council, our new media supporter, Manchester Digital the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Redeye – The Development Agency with funds from the ERDF. -

MACFEST MUSLIM Arts and CULTURE FESTIVAL

MACFEST MUSLIM ARTs AND CULTURE FESTIVAL CELEBRATING ARTS AND CONNECTING COMMUNITIES OVER 50 EVENTS JANUARY - MAY 2020 WWW.MACFEST.ORG.UK [email protected] @MACFESTUK FESTIVAL HIGHLIGHTS METALWARE FROM KEYNOTE ADDRESS FAMOUS WRITERS: THE KHALEEQ BY PROF SALIM FIRDAUSI COLLECTION AL-HASSANI CULTURAL HUBS: CREATIVE PAPER CELEBRATING OUR WOMEN OF SCIENCE CUTTING WORLD AND DIVERSE CULTURES MUSICAL FINALE SPANISH AL FIRDAUS WITH SOAS ENSEMBLE AT THE COLLECTIVE LOWRY WELCOME MUSLIM ARTS AND CULTURE FESTIVAL Welcome to our second MACFEST, a ground- Art Gallery). We are delighted to partner with breaking and award-winning Muslim Arts and Rochdale and Huddersfield Literary Festivals, Culture Festival in the North West of the UK. Rossendale Art Trail/Apna Festival, Stretford Its mission: celebrating arts, diversity and Festival and Greater Manchester Walking connecting communities. Festival. We are proud to offer you a rich feast of over 50 In addition, various schools, Colleges and the events in 16 days across Greater Manchester University of Manchester are hosting MACFEST celebrating the rich heritage of the Muslim Days, with arts and cultural activities. We are diaspora communities. There is something delighted to bring you a great line up of local, for the whole family: literature, art, history, national and international speakers, performers music, films, performance, culture, comedy, art and artists including singers and musicians from exhibitions, demonstrations, book launches, Spain and Morocco. debates, workshops, and cultural hubs. MACFEST’s opening ceremony on the 11th Join us! Over 50 events across Greater January 2020 is open to the public. Manchester and the North West are free. The venue for the packed Weekend Festival Enjoy! on 11th and 12th January, is the iconic British Muslim Heritage Centre in Whalley Range. -

North West Attractions – Paid

Top 10 North West Attractions – Paid County in which Local Authority District in % Adult Child attraction which attraction is Visitor Visitor Estimate/ Change Admission Admission Name of Attraction located located Category 2006 2007 Exact 07-06 Charge Charge 1 Windermere Lake Cruises Cumbria South Lakeland other 1267066 1274976 na 1 na na safari 2 Chester Zoo Cheshire Chester park/zoo/acquarium/aviary 1161922 1233044 na 6 14.95 10.95 GREATER 3 The Lowry MANCHESTER Salford museum/gallery 850000 850000 exact 0 na na 4 Tatton Park (NT) CHESHIRE Macclesfield historic house 770000 780000 1 na na 5 Blackpool Zoo & Dinosaur Safari LANCASHIRE Blackpool nature reserve 320000 335000 estimate 5 12.95 8.95 6 Ullswater Steamers CUMBRIA Eden other 309365 303008 estimate -2 5.20 2.60 7 Camelot Theme Park LANCASHIRE Chorley leisure/theme park 280000 270000 exact -4 18.00 18.00 8 Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery Museum CUMBRIA Carlisle museum/gallery 202716 214841 exact 6 5.20 na 9 Croxteth Hall and Country Park MERSEYSIDE Liverpool country park NA 180000 estimate NA 4.50 2.40 10 The Beatles Story Ltd MERSEYSIDE Liverpool museum/gallery 144114 155412 estimate 8 9.99 4.99 11 Liverpool Football Club MERSEYSIDE Liverpool museum/gallery 131896 143122 estimate 9 9.00 6.00 12 Ravenglass & Eskdale Railway North West Copeland steam/heritage railway 116000 122000 estimate 5 9.60 4.80 GREATER 13 Dunham Massey Hall MANCHESTER Trafford museum/gallery 111380 116656 na 5 7.70 3.85 GREATER other historic/scenic 14 East Lancashire Railway MANCHESTER Bury transport operator -

Download Full Cv

Susan Hiller Solo Exhibitions 2019 Making Visible [Susan Hiller, Anna Barriball], Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain Re-collections [Susan Hiller, Elizabeth Price, Georgina Starr], Site Gallery, Sheffield, England Die Gedanken sind Frei, Serralves Museum, Porto, Portugal 2018 Susan Hiller: Altered States, Polygon Gallery, Vancouver, Canada Susan Hiller: Social Facts, OGR, Turin, Italy Lost and Found & The Last Silent Movie, Sami Center for Contemporary Art, Norway 2017 Susan Hiller: Paraconceptual, Lisson Gallery, New York, USA 2016 Susan Hiller: Magic Lantern, Sursock Museum, Beirut, Lebanon Susan Hiller: Lost and Found, Perez Art Museum, Miami, USA Susan Hiller: Aspects of the Self 1972-1985, MOT International, Brussels, Belgium Susan Hiller: The Last Silent Movie, Frac Franche-Comté, Besancon, France 2015 Susan Hiller, Lisson Gallery, London, England 2014 Channels, Den Frie Centre of Contemporary Art, Copenhagen, Denmark Resounding (Infrared), Summerhall, The Edinburgh Art Festival, Scotland Susan Hiller, The Model, Sligo, Ireland Channels, Samstag Foundation, The Adelaide Festival, Australia Hiller/Martin: Provisional Realities (2 person: with Daria Martin), CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, USA Speaking In Tongues (3 person: with Sonia Boyce and Pavel Buchler), CCCA, Glasgow, UK Can You Hear Me? (2 person: with Shirin Neshat), Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast, Northern Ireland Sounding, The Box, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London, England Susan Hiller, Les Abattoirs, Festival International d'Art de Toulouse, France 2013 Channels, Matt’s Gallery, London Channels, Centre d’Art Contemporain La Synagogue de Delme, Delme, France 2012 Susan Hiller: From Here to Eternity, Kunsthalle Nürnberg, Germany Psi Girls, University Art Gallery, San Diego State University, San Diego, USA 2011 Susan Hiller, Tate Britain, London, England (ex. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETII-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND THEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTIIORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISII ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME III Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA eT...........................•.•........•........................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................... xi CHAPTER l:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION J THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Owls 2019 07

'e-Owls' Branch Website: https://oldham.mlfhs.org.uk/ MLFHS homepage : https://www.mlfhs.org.uk/ Email Chairman : [email protected] Emails General : [email protected] Email Newsletter Ed : [email protected] MLFHS mailing address is: Manchester & Lancashire Family History Society, 3rd Floor, Manchester Central Library, St. Peter's Square, Manchester, M2 5PD, United Kingdom JULY 2019 MLFHS - Oldham Branch Newsletter Where to find things in the newsletter: Oldham Branch News : ............... Page 2 From the E-Postbag : ................... Page 13 Other Branch Meetings : ............. Page 5 Peterloo Bi-Centenary : ................ Page 14 MLFHS Updates : ....................... Page 6 Need Help! : ................................. Page 16 Societies not part of MLFHS : ..... Page 9 Useful Website Links : ................. Page 18 'A Mixed Bag' : .............................Page 10 For the Gallery : ........................... Page 19 Branch News : Following April's Annual Meeting of the MLFHS Oldham Branch : Branch Officers for 2019 -2020 : Chairman : Linda Richardson Treasurer : Gill Melton Secretary & Webmistress : Jennifer Lever Newsletter Editor : Sheila Goodyear Technical Support : Rod Melton Chairman's remarks : Just to say that I hope everyone has a good summer and we look forward to seeing as many people as possible at our next meeting in September, in the Performance Space at Oldham Library. Linda Richardson Oldham Branch Chairman email me at [email protected] ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Editor's remarks. Hi Everyone, I just cannot believe how this year is running away ... as I start compiling this copy of the newsletter, we're just 1 week away from the longest day! I don't feel as if summer has even started properly yet! You'll find a new section added to the newsletter this month, which I have called, 'From the E- Postbag'. -

Collections Review in the North West

Gallery Oldham, Norwyn What’s in Store? Collections review in the North West 1 2 Foreword Over the last two years the Museums Association (MA) has developed Effective Collections as a UK-wide programme to improve the use of stored collections through loans and disposal. We have published guidance, such as the Disposal Toolkit, to help museums undertake responsible disposal and piloted a number of reviews of stored collections, brokering loans and permanent transfers of material as a result. The collections reviews in this publication are some of the first to actively use models set out in Effective Collections and guidance in the Disposal Toolkit, and so I’ve watched the Collections Review Project in the North West with great interest. Reviewing collections is vital for any museum considering the long term development of its collection. As well as enabling responsible disposal decisions, the case studies in this publication reveal the extra benefits that a collections review can yield – from the creativity that comes from increased collections knowledge, to the support that comes from developing relationships with other museums. Putting the resources and ideas we’ve all been working on into practice is the start of a significant culture change in museums. I hope that more museums take these ideas on board and can use this report to inform reviews of their collections. Sally Cross Collections Coordinator Museums Association 3 Contents Introduction ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Africa and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Africa and the transatlantic slave trade Arm ring trade token, The Manchester Museum, Barbados penny, TheObject University title of Manchester GalleryObject Oldham title Blackamoor, Bolton Museum and The Slave, ArchiveObject Service title People’s History Museum Questions Manilla, 1700s Slave Trade, 1791 West African drum, 1898 The Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester The Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester The Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester 1 Why did Europeans enslave Africans to work Manillas were traditional African The trade was described as George Morland was an English This painting was made as a piece This drum was collected in 1898 The drum is made with a piece horseshoe shaped bracelets triangular: ships sailed full of artist who did two paintings known of propaganda. It is not based in Ilorin, Nigeria. It was given to of manufactured cotton fabric, on plantations? made of metals such as iron, ‘exchange’ goods such as manillas, as ‘Slave Trade’ and ‘African on actual events, but represents Salford Museum and was described probably made in Britain, and bronze, copper and very rarely metals, clothing, guns and alcohol Hospitality’. He was inspired by a dramatisation of selling enslaved as ‘both rare and special and possibly in Manchester. 2 How did they justify this? gold. Decorative manillas were from Britain to Africa. Enslaved a friend’s poem to paint images Africans. European slave traders very difficult to get hold of’. The fact that British goods worn to show wealth and status Africans were transported across of slavery. The movement to end capture an African man, and Drums were a very important part became integral parts of African 3 What was life like in Africa? in Africa.