The Immediate Effects of Traditional Thai Massage on Heart Rate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

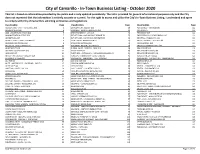

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Traditional Thai Massage Promoted Immunity in the Elderly Via Attenuation of Senescent CD4+ T Cell Subsets: a Randomized Crossover Study

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Traditional Thai Massage Promoted Immunity in the Elderly via Attenuation of Senescent CD4+ T Cell Subsets: A Randomized Crossover Study Kanda Sornkayasit 1,2,† , Amonrat Jumnainsong 2,3,†, Wisitsak Phoksawat 2,4, Wichai Eungpinichpong 5,* and Chanvit Leelayuwat 2,3,* 1 Biomedical Sciences Program, Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand; [email protected] 2 The Centre for Research and Development of Medical Diagnostic Laboratories (CMDL), Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (W.P.) 3 School of Medical Technology, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand 4 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand 5 School of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.E.); [email protected] (C.L.) † These authors contributed equally to the work presented. Citation: Sornkayasit, K.; Abstract: The beneficial physiological effects of traditional Thai massage (TTM) have been previously Jumnainsong, A.; Phoksawat, W.; documented. However, its effect on immune status, particularly in the elderly, has not been explored. Eungpinichpong, W.; Leelayuwat, C. This study aimed to investigate the effects of multiple rounds of TTM on senescent CD4+ T cell Traditional Thai Massage Promoted subsets in the elderly. The study recruited 12 volunteers (61–75 years), with senescent CD4+ T cell Immunity in the Elderly via subsets, who received six weekly 1-h TTM sessions or rest, using a randomized controlled crossover Attenuation of Senescent CD4+ T Cell study with a 30-day washout period. -

10 Meeting of the International Advisory Committee Memory of The

10th Meeting of the International Advisory Committee Memory of the World Programme Manchester, United Kingdom, 22-25 May 2011 REPORT 1. Orientation session An orientation meeting was held on the afternoon of 22 May, the day of arrival of participants. Ms Joie Springer welcomed all new members of the International Advisory Committee (IAC) and first-time attendees, including observers, to the Programme. She introduced the Memory of the World (MoW) Programme, explaining its structures, the different registers, the work of its committees and expectations for the roles they should play in achieving the Programme's objectives. Group Photo © F. McCarthy 2. Welcome address by UK Representative The meeting was addressed by Mr David Dawson, chairman of the UK Memory of the World National Committee, who extended a warm welcome to all participants and hoped that the deliberations would be very productive. 3. Opening of the session by the representative of the Director-General of UNESCO The 10th IAC session was opened by Ms Joie Springer on behalf of the Director-General of UNESCO, Ms Irina Bokova. Ms Springer welcomed the IAC members, members of different MoW committees and observers, and thanked the UK National Committee, especially Mr George Boston, Mr David Dawson and Mr Ian White for their hard work and preparations for the organization of the IAC meeting. Ms Springer expressed the wish to heighten the focus of the Programme and thanked the Polish authorities for organizing the just concluded 4th International Conference which helped to highlight areas of concern, included the need cited by the Director-General to "further sensitize and educate the wider public about the importance of documentary heritage for collective memory". -

Group Directory2o21 Mandarin Oriental’S Acclaimed Collection of Luxury Hotels Awaits You

GROUP DIRECTORY2O21 Mandarin Oriental’s acclaimed collection of luxury hotels awaits you. Perfectly located in the world’s most prestigious destinations, Mandarin Oriental welcomes you with legendary service and exquisite facilities. Wherever you travel, you will be greeted with 21st-century luxury that is steeped in the values of the Orient. CONTENTS Legendary Service 4 Design & Architecture 6 Innovative Dining 8 The Spas at Mandarin Oriental 10 The Residences at Mandarin Oriental 12 Asia-Pacific 14 Europe, Middle East & Africa 42 America 76 Fans of M.O. 90 Gift Card 92 Hotel Amenities 94 MANDARIN ORIENTAL DESTINATIONS Asia-Pacific Bangkok Beijing Guangzhou Hong Kong Jakarta Kuala Lumpur Macau Sanya Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Europe, Middle East and Africa America Abu Dhabi London Boston Barcelona Madrid Canouan Bodrum Marrakech Miami Doha Milan New York Dubai Munich Santiago Geneva Paris Washington DC Istanbul Prague Lake Como Riyadh LEGENDARY SERVICE Discreet, personalized service lies at the heart of everything we do. Delivering this promise are our dedicated colleagues, our most precious asset. They take pride in delighting our guests, meeting their every need and surpassing their expectations at all times. 4 5 DESIGN & ARCHITECTURE Reflecting a strong sense of place, our hotels offer a unique mix of 21st century luxury and Oriental charm. We work with some of the most respected architects and designers in the world to create a collection of stunning, individually-designed properties that are truly in harmony with their setting. 6 7 INNOVATIVE DINING Mandarin Oriental hotels are renowned for their innovative restaurants and bars. Our exceptional chefs include a host of internationally acclaimed epicures and local rising stars. -

Feeling Sick After Renovation? Gold Fineness Consumer Alerts MICA(P) NO

MICA(P) NO. 001/07/2014 • 2014 ISSUE 1 ISSN 0217-8427 • S$4.80 feeling sick after renovation? gold fineness consumer alerts MICA(P) NO. 001/07/2014 • 2014 ISSUE 1 ISSN 0217-8427 • S$4.80 contents the consumer 00 19 feeling sick after renovation? gold fineness consumer alerts 01 casenotes The Editorial Team 02 SPRING Singapore Chief Editor Richard Lim 04 SPRING CPS comic 13 Editor casebriefs Larry Haverkamp 05 Jayems Dhingra feeling sick after 14 gold fineness Feeling Sick AfterProduction Editor renovation? Matthew Choong Renovation? 08 16 Contributors cycling safely goldreal Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) 19 National Environment Agency (NEA) 09 Gold Fineness private data protection Singapore Assay Office (SAO) SPRING CPS comic SPRING Singapore 24 10 subscription form Consumer AlertsMr Jayems Dhingra sayit@case Ms Brenda Teng Editorial Consultant Dr Ang Peng Hwa Design & Production Tangram Design Studio Like this issue? Think we missed 05 something vital? Tell us at [email protected] 08 Consumers Association of Singapore 170 Ghim Moh Road #05-01 Ulu Pandan Community Building Singapore 279621 Tel: 6100 0315 Fax: 6467 9055 Feedback: [email protected] 16 14 www.case.org.sg casenotes Dear readers, As part of the mission of CASE, we constantly review our processes to ensure that our activities are done with the interests of the consumer in mind. Allow me to highlight several initiatives taken by CASE to protect the interest of consumers in Singapore. In April 2013, CASE commissioned a test on air purifiers. We noticed that more consumers were purchasing air purifiers for their usage and individual consumers the consumer will not have the resources to carry out tests to substantiate the claims made by the manufacturer. -

Northern Thailand

© Lonely Planet Publications 339 Northern Thailand The first true Thai kingdoms arose in northern Thailand, endowing this region with a rich cultural heritage. Whether at the sleepy town of Lamphun or the famed ruins of Sukhothai, the ancient origins of Thai art and culture can still be seen. A distinct Thai culture thrives in northern Thailand. The northerners are very proud of their local customs, considering their ways to be part of Thailand’s ‘original’ tradition. Look for symbols displayed by northern Thais to express cultural solidarity: kàlae (carved wooden ‘X’ motifs) on house gables and the ubiquitous sêua mâw hâwm (indigo-dyed rice-farmer’s shirt). The north is also the home of Thailand’s hill tribes, each with their own unique way of life. The region’s diverse mix of ethnic groups range from Karen and Shan to Akha and Yunnanese. The scenic beauty of the north has been fairly well preserved and has more natural for- est cover than any other region in Thailand. It is threaded with majestic rivers, dotted with waterfalls, and breathtaking mountains frame almost every view. The provinces in this chapter have a plethora of natural, cultural and architectural riches. Enjoy one of the most beautiful Lanna temples in Lampang Province. Explore the impressive trekking opportunities and the quiet Mekong river towns of Chiang Rai Province. The exciting hairpin bends and stunning scenery of Mae Hong Son Province make it a popular choice for trekking, river and motorcycle trips. Home to many Burmese refugees, Mae Sot in Tak Province is a fascinating frontier town. -

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

Provided by Hee Sook UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage» Intergovernmental Committee 14.COM The Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage met in Bogota, Colombia from 9 to 14 December. The gathering at the Agora Bogotá Centro de convenciones was the first time the Committee met in Latin America and the Caribbean. Five Inscriptions to the Urgent Safeguarding List (item 10.a) 1. Botswana: Seperu folkdance and associated practices/Le seperu, danse populaire et pratiques associées 2. Kenya: Rituals and practices associated with Kit Mikayi shrine/Les rituels et pratiques 5associés au sanctuaire de Kit Mikayi 3. Mauritius: Sega tambour Chagos/Le séga tambour des Chagos 4. Philippines: Buklog, thanksgiving ritual system of the Subanen/Le Buklog, système de rituels de gratitude des Subanen 5. Belarus: Spring rite of Juraŭski Karahod/Le rite du printemps de Juraǔski Karahod 35 inscriptions from 42 nominations to the Representative List (item 10.b) 1. Armenian letter art and its cultural expressions, Armenia 2. Transhumance, the seasonal droving of livestock along migratory routes in the Mediterranean and in the Alps, Austria, Greece, Italy 3. Date palm, knowledge, skills, traditions and practices, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Mauritania 4. Ommegang of Brussels, an annual historical procession and popular festival, Belgium 5. The festival of the Santísima Trinidad del Señor Jesús del Gran Poder in the city of La Paz, Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 6. Traditional technique of making Airag in Khokhuur and its associated customs, Mongolia 7. Cultural Complex of Bumba-meu-boi from Maranhão, Brazil 8. Morna, musical practice of Cabo Verde, Cabo Verde 9. -

2021 Select Directory

Quick Reference Card in Back Group Health Cooperative of South Central Wisconsin 2021 Select Directory Group Health Cooperative of South Central Wisconsin (GHC-SCW) ghcscw.com MK20-88-0(7.20)O NEW MEMBER INFORMATION Table of Contents About This Provider Directory This Provider Directory is accurate at the time of WELCOME TO THE GHC SELECT PLAN ................. 3 printing. Find the most current information about our wide selection of care providers online. CARE GUIDE ...................................................... 4 1) Visit ghcscw.com. Quick Care ................................................ 4 2) Select the “Clinic or Provider” button. 3) Select your network from the drop-down menu. Pharmacy ................................................. 5 4) Select either “Search for a Provider” or GHCMyChartSM .......................................... 6 “Search for a Clinic.” PRIMARY CARE PROVIDERS AND CLINICS ............ 7 Need help selecting a Primary Care Provider (PCP)? Care Teams at GHC-SCW ............................ 7 Call (608) 828-4853 or toll-free at (800) 605-4327 and request Member Services. GHC-SCW Clinics ....................................... 8-14 For complete details about what is covered under your SPECIALTY AND ANCILLARY SERVICE GHC-SCW Plan, please refer to your Member Benefits Summary, Member Certificate and Plan Amendments, PROVIDERS AT GHC-SCW ................................... 15 contact your employer or call Member Services. Chiropractic Services .................................. 16 Clinical Health Education -

Culture, Identity and Globalisation in Southeast Asian Art

Culture, Identity and Globalisation in Southeast Asian Art A Publication of the SEAMEO Regional Centro for Archaeology and Fine Arts Volume 14 Number 1 January - April 2004 • ISSN 0858-1975 SEAMEO-SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts SPAFA Journal is published three times a year by the SEAMEO-SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts. It is a forum for scholars, researchers and professionals on archaeology, performing arts, visual arts and cultural activities in Southeast Asia to share views, research findings and evaluations. The opinions expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of SPAFA. SPAFA's objectives : • Promote awareness and appreciation of the cultural heritage of Southeast Asian countries through preservation of archaeological and historical artifacts, and traditional arts; • Help enrich cultural activities in the region; • Strengthen professional competence in the fields of archaeology and fine arts through sharing of resources and experiences on a regional basis; • Increase understanding among the countries of Southeast Asia through collaboration in archaeological and fine arts programmes. The SEAMEO Regional Centre for Archaeology Editorial Board and Fine Arts (SPAFA) promotes professional Pisit Charoenwongsa competence, awareness and preservation of Professor Khunying Maenmas Chavalit cultural heritage in the fields of archaeology and fine arts in Southeast Asia. It is a regional centre Assistants constituted in 1985 from the SEAMEO Project in Lynn Hartery Archaeology and Fine Arts, which provided the Tang Fu Kuen acronym SPAFA. The Centre is under the aegis of Vassana Taburi the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Wanpen Kongpoon Organization (SEAMEO). -

Natural Healing Institute of Naturopathy, Inc. (NHI)

Natural Healing Institute of Naturopathy, Inc. (NHI) RESIDENTIAL COURSE CATALOG 515 Encinitas Blvd., Suite 201, Encinitas, CA, 92024 Phone: (760) 943-8485 Fax: (760) 943-9477 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nhicollege.com CAMTC Approval code ________ State-Approved & Certified Nutritionist Massage Therapist (MT) State-Licensed Consultant (CNC)™ Massage Technician Vocational College Certified Clinical Master Exercise / Sports Therapist Herbalist (CCMH)™ Spa & Massage Therapist Holistic Health Thai Massage Therapist Programs & Classes Practitioner (HHP) Lomi-Lomi Therapist for Certificate of Naturopathic Practitioner Certified Aromatherapist (CA) Completion and/or (NP) Professional License Yoga Instructor, Somatics & Movement Therapist (YISMT)™/ RYT COURSE CATALOG Message from our Founder-Director 3 NHI Directors and Administration 4-5 Benefits of NHI 6 About NHI – Approval, Licensing, Transfers, Enrollment, Payment 7 - 9 Options, Cancellation & Refunds Certified Nutritionist Consultant (CNC)™ 10 - 11 Certified Clinical Master Herbalist (CCMH)™ 12 - 13 Massage Technician 14 Massage Therapist (MT) 15 - 17 Holistic Health Practitioner (HHP) 18 - 19 Spa & Massage Therapist (MT) 20 - 21 Sports Therapist & Performance Enhancement (MT) 22 - 23 Certified Aromatherapist 24 Yoga Instructor, Somatics and Movement Therapist (YISMT)™ 25 Thai Massage Therapist 26 Lomi-Lomi Hawaiian Healing Arts 27 Naturopathic Practitioner (NP) 28-30 Additional MT & HHP Electives 31-39 NHI Faculty & Advisors 40-44 FAQ’s 45 A Our Mission at NHI College To foster health, healing, joy, meaning, awareness and appreciation. To empower our family of students, clients and staff towards growth and expansion. To provide exceptional Natural Healing or Naturopathic education. To provide the highest caliber faculty based on B their dedication and ability to inspire and transmit Holistic Health principles. -

Effects of Thai Massage on Spasticity in Young People with Cerebral Palsy

Effects of Thai Massage on Spasticity in Young People with Cerebral Palsy Pisamai Malila MSc*,**, Kantarakorn Seeda BSc*, Savet Machom BSc*, Nutthakan Salangsing BSc*, Wichai Eungpinithpong PhD*,** * Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand ** Research Center in Back, Neck, Other Joint Pain and Human Performance (BNOJPH), Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand Objective: To determine the effects of Thai massage on muscle spasticity in young people with cerebral palsy. Material and Method: Young people with spastic diplegia, aged 6-18 years old, were recruited from the Srisungwan School in Khon Kaen Province. Spasticity of right quadriceps femoris muscles was measured using Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) at pre- and immediately post 30-minute session of Thai massage. Thai massage was applied on the lower back and lower limbs. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test was used to compare the outcome between pre- and post treatment. Results: Seventeen participants with spastic diplegia aged 13.71+3.62 years old participated. A significant difference of MAS was observed between pre- and post treatment (1+, 1; p<0.01). No adverse events were reported. Conclusion: Thai massage decreased muscle spasticity and is suggested to be an alternative treatment for reducing spasticity in young people with cerebral palsy. Keywords: Thai massage, Spasticity, Cerebral palsy, Diplegia, Modified ashworth scale J Med Assoc Thai 2015; 98 (Suppl. 5): S92-S96 Full text. e-Journal: http://www.jmatonline.com Cerebral palsy is a neurological disorder found lines (the sen sib) that always involve tight muscles of in children, which affects motor functions of the brain. -

Traditional Thai Massage

TRADITIONAL THAI MASSAGE Peanchai Khamwong (ผศ. ดร. เพียรชัย ค ำวงษ์) Traditional Thai Massage Definition Thai massage is the name of the traditional massage techniques of Thailand, used to alleviate personal discomfort and promote general well being. ..is developed in Thailand, and influenced by the traditional medicine systems of India, China, and Southeast Asia. History of TTM The founder of Thai massage and medicine is said to have been Shivago Komarpaj (Jīvaka Komarabhācca), who is said in the Pāli Buddhist Canon to have been the Buddha's physician over 2,500 years ago. Drawings of accpressure points on "Sen" lines at Wat Pho temple in Bangkok, Thailand. “Rural” and “Royal” traditions Wat Pho temple in Bangkok The center of the Royal Tradition of Thai medicine The Shivaga Komaraphat Institute A traditional medicine hospital in Chiang Mai, northern Thailand Medical and Physiological principle • The purpose of Thai massage is to bring wellness to the whole body system, via the manipulation of the energy lines, encouraging health promotion. • There are 72,000 lines (sen) Theory The 10 ‘sen’ or energy lines that run through the body. By stimulating these, the masseur can alleviate suffering and bring strength and harmony back to the body. Physiological & psychological effects • Increases blood circulation and removes waste products. • Relaxation of muscle tissue and relieving pain. • Increases the range of motion of the joints. • Alleviates disorders of the digestive system as well, by helping with constipation, relieving the tension of the visceral organs. • Psychologically the patient feels warmth and touching, general relaxation and a deep sense of over all well being.