ACCORD VISION DOCUMENT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

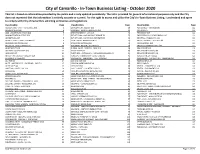

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

What Is Commonly Known As Salt -Nacl- Is a Deceivingly Simple

K. Хуесо, В. Карраско. In sale Salus: соли и соленые болотные угодья Европы для сохранения здоровья УДК 577.151.01 DOI: 10.18101/2306-2363-2017-4-11-25 * IN SALE SALUS: HEALTH PROVISION FROM SALT AND SALINE WETLANDS IN EUROPE © Kortekaas K. Hueso Institute of Saltscapes and Salt Heritage (IPAISAL), Apartado de Correos 50 28450 Collado Mediano, Spain ICAI Higher Technical School of Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universidad Pontificia de Comillas Alberto Aguilera 25, Madrid, Spain © Vayá J-F. Carrasco Institute of Saltscapes and Salt Heritage (IPAISAL), Apartado de Correos 50 28450 Collado Mediano, Spain Among the often cited 14,000 uses of salt, many are related to wellness and health. Its different physical-chemical properties allow many health-related applications of salt itself, brine, mother lay and saline muds. Salt can be used as skin rubs or in blocks, for building halochambers; inhaled as aerosols or even ionised by lamps. Brine can be ingested or used for bathing and exercising in it. Mother lay is usually employed as a basis for cosmetics and skin treatments and muds are traditionally applied directly on the skin for similar ailments. Many of these applications have been known since the Antiquity and are still in use today. Some have disappeared or are only known at local scale, while others are growing in popularity, amid the surge of spa and wellness facilities worldwide. The also increasingly popular natural and alternative treatments have included salt-related healing. In this contribution, we will review among others the traditional uses of brine and salt for health provision; the therapeutic and wellness uses of mother lay and mud as a side activity for traditional salinas, some of which have built ad hoc spa and wellness centres; the now widespread phenomenon of salt caves and mines for halotherapy and the historical spas built around saline lakes, now in disuse. -

Vision Therapy and Post-Concussion Syndrome Management: a Case Report Elizabeth Murray OD, Katie Connolly OD

Vision Therapy and Post-Concussion Syndrome Management: A Case Report Elizabeth Murray OD, Katie Connolly OD Abstract: Current therapy for post-concussion syndrome with visual symptoms are to rest and decrease visual demand. This case looks at vision therapy for first line treatment when decreasing visual demand is not ideal. I. Case History On 5/30/2017, a 37 year old white male presented for persistent visual symptoms following a traumatic brain injury to the occipital lobe with torsion on the brain stem. The injury occurred on 4/3/2017 from a motor vehicle accident, and he had since been cleared from cognitive rest. At the time of the accident, he reported no loss of consciousness but did have post traumatic amnesia. Initially, he reported feeling fine, but his symptoms progressively worsened. He denied blur and diplopia, but was symptomatic for significant cognitive fatigue, gaze instability, visual stimuli triggered headaches, photophobia, and noise sensitivity. He is a pediatric oncologist with significant visual and cognitive demanding duties that exacerbate his symptoms. Ocular and medical history were unremarkable prior to the accident. At the time, he was taking Fioricet and Amitriptyline as directed for headaches and to aid in sleep, respectively. He had been seeing a Chiropractor for vestibular therapy that included some oculomotor therapy and planned to begin cognitive therapy at an outpatient rehabilitation hospital. II. Pertinent findings Entering distance visual acuities were 20/20 OD, OS and OU and near visual acuities were 20/20 OD, 20/25-1 OS, and 20/15-1 OU, without correction. Pupils and extraocular muscles were unremarkable. -

Medical Balneology; Recent Global Developments

Medical Balneology; recent global developments Müfit Zeki Karagülle, MD, PhD XXV (XXIX) Zjazd Balneologiczny Balneological Congress of the Polish Association of Balneology and Physical Medicine 10-13 September 2015, Polańczyk Balneology/ISMHBalneology/ISMH goesgoes globalglobal IntensifiedIntensified andand enrichedenriched globalglobal scientificscientific researchresearch inin BalneologyBalneology • Balneological articles published in peer reviewed international journals has been continually increasing since last decade • The authors from countries like Brazil, Japan, China, Taiwan, South Korea and India are publishing more in addition to classical European balneological countries like France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria • The contribution to this development from eastern European countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Turkey is also increasing. ResearchResearch methodology;methodology; betterbetter qualityquality We comprehensively searched data bases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English between July 2005 and December 2013. By using JADAD calculation we evaluated also the quality of the RCTs evaluating balneotherapy and spa therapy for the treatment of low back. RandomizedRandomized controlledcontrolled trialstrials JadadJadad scores,scores, journalsjournals andand impactimpact factorsfactors Jadad Journal Author, (year) Journal quality impact treatment score factor Balogh et al. (2005) ForschendeKomplementärmedizin/Research in 1 1,279 Balneotherapy Complementary Medicine Leibetseder et al. ForschendeKomplementärmedizin/Research in 0 1,279 (2007) Spa therapy Complementary Medicine Demirel et al. (2008) Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal 2 0,613 Spa therapy Rehabilitation Kulisch et al. (2009) Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 5 2,134 Spa therapy Doğan et al. (2011) Southern Medical Journal 1 0,915 Spa therapy Kesiktaş et al. (2012) Rheumatology International 3 2,214 Spa therapy Tefner et al. (2012) Rheumatology International 3 2,214 Balneotherapy Gremeaux et al. -

Plan Q Full Benefit Description

B E N E F I T D E S C R I P T I O N State Employee Health Plan This booklet describes the health benefits that the Kansas State Employees Health Care Commission provides to Members and their Dependents. These benefits are funded by: The Kansas State Employees Health Care Commission Third Party Administrator (TPA): : Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas has been retained to administer claims under this Plan. The TPA provides Administrative Services Only pursuant to this Benefit Description, including claims processing and administration of appeals and grievances. For answers to questions regarding eligibility for benefits, payment of claims, and other information about this Plan contact: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas 1133 SW Topeka Blvd Topeka, KS 66629 By Phone 785-291-4185 or Toll Free at 1-800-332-0307 www.bcbsks.com/state Company is not the insurer under this Program and does not assume any financial risk or obligation with respect to claims. Plan Q Benefit Description 2021 Section I Coverage ................................................................................................. 1 Part 1: General Provisions ................................................................................ 1 Responsibilities of the Third Party Administrator (TPA) ..................................... 1 Case Management/Cost Effective Care ............................................................ 1 How to Contact the TPA .................................................................................... 2 Services from Non Network Providers -

Year in Review Issue

Gregg’s LANDING The exclusiveG newsletter for the residentsLife of Gregg’s Landing January 2021 2020 YEAR IN REVIEW ISSUE YOUR STORIES. YOUR PHOTOS. YOUR COMMUNITY. New Year (finally), New You ! LEAVE IT TO TOPTEC $500 OFF! WE'LL TAKE CARE OF IT. YEAR END SPECIAL $85.00 BRACES Furnace Tune-up INVISALIGN Special *12/1/2020 - 1/31/2021 COMPREHENSIVE TREATMENT ONLY **COUPON MUST BE PRESENT Don't pay until 2021 when you nance a new Lennox* YOUR SPECIALIST FOR: systemfor as little as $132 a month. Early Treatment • Adult Treatment Plus get up to $1,200 in rebates. Ronald S. Jacobson Raymond Y. Tsou No contact service call policy – Techs. D.D.S., M.S. D.M.D., M.S. Diamond Plus Provider wears face masks, gloves & booties IL. Lic. #055-042909 Visit us Online Vernon Hills Office: Chicago Office: 280 W. Townline Rd. 4200 W. Peterson Ave. JTORTHO.COM Suite 220 Suite 116 Vernon Hills, IL 60061 Chicago, IL 60646 Visit our Doctors at our Vernon Hills or Chicago Location 847-816-0633 773-545-5333 2 Gregg's Landing Life • January 2021 January 2021 • Gregg's Landing Life 3 847-780-8200 You can purchase sessions, membership plans and gift cards... please call or Visit our Facebook page or website for promotions. Northshoresalt.com CONDITIONS BENEFITS • Asthma • Clear Pollens, Pollutants, Toxins & Airways • Cough • Reduce Bronchial Inflammation • Sinusitis • Relieve Skin Conditions such as Dermatitis, • COPD Eczema, & Psoriasis • Bronchitis • Improve Lung Function • Stress • Strengthen the Immune System against • Ear Infection Cold, Flu, & Lung Irritants • Allergies • Reduce Triggers that Promote Respiratory Illness • Eczema • Clean Nasal Cavities and Sinuses • Psoriasis • Cystic Fibrosis WE SELL 1282 Old Skokie Rd. -

Allergy.2013.3.3.155 Allergy Asia Pac Allergy 2013;3:155-160

pISSN 2233-8276 · eISSN 2233-8268 Asia Pacific Original Article http://dx.doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.3.155 allergy Asia Pac Allergy 2013;3:155-160 The pH of water from various sources: an overview for recommendation for patients with atopic dermatitis Kanokvalai Kulthanan, Piyavadee Nuchkull*, and Supenya Varothai Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700, Thailand Background: Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) have increased susceptibility to irritants. Some patients have questions about types of water for bathing or skin cleansing. Objective: We studied the pH of water from various sources to give an overview for physicians to recommend patients with AD. Methods: Water from various sources was collected for measurement of the pH using a pH meter and pH-indicator strips. Results: Bottled drinking still water had pH between 6.9 and 7.5 while the sparkling type had pH between 4.9 and 5.5. Water derived from home water filters had an approximate pH of 7.5 as same as tap water. Swimming pool water had had pH between 7.2 and 7.5 while seawater had a pH of 8. Normal saline and distilled water had pH of 5.4 and 5.7, respectively. Facial mineral water had pH between 7.5 and 8, while facial makeup removing water had an acidic pH. Conclusion: Normal saline, distilled water, bottled sparkling water and facial makeup removing water had similar pH to that of normal skin of normal people. However, other factors including benefits of mineral substances in the water in terms of bacteriostatic and anti- inflammation should be considered in the selection of cleansing water. -

TREATMENT of CANCER with CHINESE HERBAL MEDICINE Signe E Beebe DVM, CVA, CVCH, CVT Integrative Veterinary Center Sacramento, California, USA

TREATMENT OF CANCER WITH CHINESE HERBAL MEDICINE Signe E Beebe DVM, CVA, CVCH, CVT Integrative Veterinary Center Sacramento, California, USA The focus of this discussion is on the use of Chinese herbal medicine to treat cancer. Acupuncture and Chinese food therapy are typically combined with Chinese herbs in the treatment of cancer. In addition, European mistletoe (IscadorR, HelixorR) and other integrative therapies such as intravenous Vitamin C can also be used in combination with Chinese medicine to treat cancer. The incidence of cancer in pet animals has been gradually increasing over the past few decades and the features of cancer (tumor genetics, biological behavior and histopathology) in dogs appear to parallel that of humans (Paoloni, M., Khanna C., Science and Society: Translation of New Cancer Treatments from Pet Dogs to Humans, Nature Review Cancer, 2008:8:147-156). Cancer incidence increases with age and according to the AVMA is the leading cause of death in dogs 10 years of age and older. Several European cancer group registries have been tracking and recording the occurrence of spontaneous tumors in pet animals as well. Cancer or malignant neoplasia is a class of disease that involves tissues with an altered cell population that operates independently of normal cellular controls. Three properties differentiate them from benign tumors; cancers grow uncontrollably, invade and destroy adjacent tissues and can metastasize and spread to other parts of the body via blood and or lymphatic circulation. Cancers consume body resources, grow at the expense of the individual and provide no benefit to the body. The most common cancers reported involved the skin (mast cell tumor), mammary glands (adenocarcinoma) and lymph tissue (lymphoma). -

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: an Overview

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: an overview Amber Hammontree, LPC Clinical Trainer Georgia Families 360° GAPEC-1204-16 March 2016 1 Learning objectives • Understand the basic concepts of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) • Identify the symptoms/disorders that CBT is used to treat • Understand evidence-based treatment • Discuss the strengths and limitations of CBT as a treatment model 2 What is cognitive behavioral therapy? • Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) combines principals of both cognitive and behavioral therapies. • Cognitive therapy emphasizes the role of thinking in “how we feel and act.” • Therapy focuses on: ― Identifying negative patterns of thinking ― How to change these unhealthy thoughts to healthier beliefs Healthy thoughts will then lead to more desirable reactions and outcomes. 3 What is cognitive behavioral therapy? (cont.) • Behavioral therapy focuses on replacing damaging habits with pro-social behaviors through skill building. This is done by: ― Focusing on decreasing the connections between stimuli (people, situations or events) and negative reactions to them. ― Learning and applying new skills to improve reactions. Additional approaches to CBT Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) Rational Living Therapy (RLT) Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT) 4 Basic principles of CBT CBT focuses on exploring the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviors. What we think affects how we act and feel. Thought What we feel affects what we think and do. What we do affects how we think and feel. Feelings Behavior 5 CBT terminology • CBT views behavior as either "adaptive" or "maladaptive", "learned" vs "unlearned", and "rational" vs "irrational." • Behavior that is rational meets these three criteria: ̶ It is based on fact ̶ It helps us achieve our goals ̶ It helps us feel how we want to feel • Behavior that does not meet these criteria is not rational. -

The Immediate Effects of Traditional Thai Massage on Heart Rate

Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies (2011) 15,15e23 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/jbmt RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED COMPARATIVE STUDY The immediate effects of traditional Thai massage on heart rate variability and stress-related parameters in patients with back pain associated with myofascial trigger points Vitsarut Buttagat, B.Sc., M.Sc., PhD candidate a,*, Wichai Eungpinichpong, B.Sc., M.Sc., PhD a, Uraiwon Chatchawan, B.Sc., M.PH., PhD a, Samerduen Kharmwan, MD b a Division of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand b Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand Received 29 December 2008; received in revised form 13 June 2009; accepted 16 June 2009 KEYWORDS Summary The purpose of this study was to investigate the immediate effects of traditional Massage; Thai massage (TTM) on stress-related parameters including heart rate variability (HRV), Traditional Thai anxiety, muscle tension, pain intensity, pressure pain threshold, and body flexibility in patients massage; with back pain associated with myofascial trigger points. Thirty-six patients were randomly Myofascial trigger point; allocated to receive a 30-min session of either TTM or control (rest on bed) for one session. Back pain; Results indicated that TTM was associated with significant increases in HRV (increased total Randomized control power frequency (TPF) and high frequency (HF)), pressure pain threshold (PPT) and body flex- trial ibility (p < 0.05) and significant decreases in self-reported pain intensity, anxiety and muscle tension (p < 0.001). For all outcomes, similar changes were not observed in the control group. -

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: an Overview

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: an overview Amber Hammontree, LPC Clinical Trainer Georgia Families 360° GAPEC-1204-16 March 2016 1 Learning objectives • Understand the basic concepts of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) • Identify the symptoms/disorders that CBT is used to treat • Understand evidence-based treatment • Discuss the strengths and limitations of CBT as a treatment model 2 What is cognitive behavioral therapy? • Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) combines principals of both cognitive and behavioral therapies. • Cognitive therapy emphasizes the role of thinking in “how we feel and act.” • Therapy focuses on: ― Identifying negative patterns of thinking ― How to change these unhealthy thoughts to healthier beliefs Healthy thoughts will then lead to more desirable reactions and outcomes. 3 What is cognitive behavioral therapy? (cont.) • Behavioral therapy focuses on replacing damaging habits with pro-social behaviors through skill building. This is done by: ― Focusing on decreasing the connections between stimuli (people, situations or events) and negative reactions to them. ― Learning and applying new skills to improve reactions. Additional approaches to CBT Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) Rational Living Therapy (RLT) Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT) 4 Basic principles of CBT CBT focuses on exploring the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviors. What we think affects how we act and feel. Thought What we feel affects what we think and do. What we do affects how we think and feel. Feelings Behavior 5 CBT terminology • CBT views behavior as either "adaptive" or "maladaptive", "learned" vs "unlearned", and "rational" vs "irrational." • Behavior that is rational meets these three criteria: ̶ It is based on fact ̶ It helps us achieve our goals ̶ It helps us feel how we want to feel • Behavior that does not meet these criteria is not rational. -

Unit 1 Psychoanalysis, Psychodynamic and Psychotherapy

UNIT 1 PSYCHOANALYSIS, PSYCHODYNAMIC AND PSYCHOTHERAPY Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Psychotherapy 1.2.1 Essentials of Psychotherapy 1.3 Psychoanalysis 1.3.1 Phases in the Evolution of Psychoanalysis 1.3.2 Brief History of Psychoanalysis 1.3.3 The Work of a Psychoanalyst 1.3.4 Goals of Psychoanalysis 1.4 Techniques in Psychoanalysis 1.4.1 Maintaining the Analytical Framework 1.4.2 Free Association 1.4.3 Dream Analysis 1.4.4 Interpretation 1.4.5 Analysis and Interpretation of Resistance 1.4.6 Analysis of Transference 1.4.7 Counter Transference 1.5 Psychodynamic Therapies 1.5.1 Freudian School 1.5.2 Ego Psychology 1.5.3 Object Relations Psychology 1.5.4 Self Psychology 1.6 Differences between Psychodynamic Therapy and Psychoanalysis 1.7 Let Us Sum Up 1.8 Unit End Questions 1.9 Suggested Readings 1.0 INTRODUCTION In this unit we will be dealing with psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and other related therapies. It provides a detailed account of psychoanalysis and presents the component factors in the same. We then discuss the essentials of Psychotherapy and point out its importance. Then we take up psychoanalysis and as the first step we elucidate the evolution of psychoanalysis and then follow it up by presenting a history of psychoanalysis. Then we take up the functions of a psychoanalyst and detail the same. This is followed by the goals of psychoanalysis and the techniques of psychoanalysis. The next section deals with the psychodynamic therapies and their significance. Then we point out the differences between Psychodynamic Therapy and Psychoanalysis 5 Counselling: Models and Approaches 1.1 OBJECTIVES After completing this unit, you will be able to: • Discuss the concept of psychotherapy; • Define psychoanalysis; • Describe the goals of psychoanalysis; • Identify the difference between psychodynamic therapy and psychoanalysis; and • Explain the techniques like dream analysis and free association used by the psychotherapist.