The Stobbe Vane: Tacking Upwind with the Self-Steering Vane by Mike Stobbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analytical Approach to the Question of a Clock Change

An Analytical Approach to the Question of a Clock Change by Samuel Halpern One of the ongoing arguments that continues to be brought up is the question of whether or not clocks on Titanic were put back some time before the accident took place Sunday night, April 14, 1912. Some of the deck crew, awakened by the accident at 11:40 p.m. ship’s time, thought that it was close to the time that they were due to take their watch on deck, which would be at 12 o’clock. Despite Boatswain’s Mate Albert Haines, who was awake and on duty at the time, testifying that “The right time, without putting the clock back, was 20 minutes to 12,” there are some that try to argue that a 24 minute clock adjustment had already taken place, and the time of the accident on an unadjusted clock still keeping April 14th time would have been 4 minutes past 12. The underlying question that would resolve this issue is the run time from noon Sunday to the time of the accident. If the run time from noon to the time of the accident was 11 hours 40 minutes, then no clock change had yet taken place, and the time of collision was 11:40 p.m. in unadjusted hours. If the run time was more than 12 hours, then there was a clock change of some 23 or 24 minutes, and the time of collision was 11:40 p.m. in adjusted hours. It really is that simple. So how do we determine the actual run time from the available evidence that does not have to rely on subjective estimates such as time intervals or other measures that people may have perceived? The answer is to take an analytical approach to the problem using the taffrail log mileage data offered by quartermasters George Rowe and Robert Hichens at the inquiries. -

Gunwale (Canoe Rails) Repair Guide Wood Gunwale Repair

Gunwale (Canoe Rails) Repair Guide Wood Gunwale Repair Canoes with fine woodwork are a tradition at Mad River Canoe. The rails, seats and thwarts on your Mad River Canoe are native Vermont straight-grained ash, chosen for its resiliency, strength and aesthetic appearance. Unlike aluminum or plastic materials, white ash will not kink upon impact and cause undue damage to the canoe hull. There are more options involved in repair of wood gunwales than with vinyl or aluminum, making this section a bit longer than the corresponding instructions for other types of rails. Don't let the length of this document intimidate you - here's an overview of this section to help you plan your repair strategy: General Information - Everyone should read this section. Pre-installation preparation - Everyone should read this section. Gunwale replacement instructions - How to replace both rails of your canoe. Replacing Gunwales with inset decks (including complete deck replacement) - If your canoe has inset decks you will likely have to replace them when you replace your rails. The other option is: Short-splicing method to preserve original inset decks when rerailing - You may cut the existing inwales of your canoe to avoid replacing your existing deck. The new inwale must be carefully spliced to the section of existing inwale. Installation of a 4' splicing section - If you have damage to a small section of gunwale, you can splice in a replacement section on the inside, outside or both. General Information Ordering replacement ash gunwales Rails can be ordered from an authorized Mad River dealer. Replacement ash rails are available for all Mad River Canoes. -

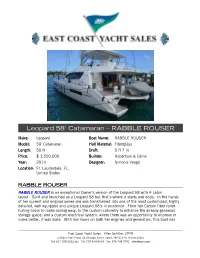

Leopard 58' Catamaran – RABBLE ROUSER

Leopard 58' Catamaran – RABBLE ROUSER Make: Leopard Boat Name: RABBLE ROUSER Model: 58' Catamaran Hull Material: Fiberglass Length: 58 ft Draft: 5 ft 7 in Price: $ 1,550,000 Builder: Robertson & Caine Year: 2014 Designer: Simonis Voogd Location: Ft. Lauderdale, FL, United States RABBLE ROUSER RABBLE ROUSER is an exceptional Owner’s version of the Leopard 58 with 4 cabin layout. Built and launched as a Leopard 58 but that’s where it starts and ends. In the hands of her current and original owner she was transformed into one of the most customized, highly detailed, well equipped and unique Leopard 58’s in existence. From her Carbon fiber roller furling boom to make sailing easy, to the custom cabinetry to enhance the already generous storage space, and a custom electrical system, where there was an opportunity to improve or make better, it was done. With low hours on both her engines and generators, this boat has East Coast Yacht Sales - Allen Schiller, CPYB at Dion's Yacht Yard, 23 Glendale Street, Salem, MA 01970, United States Tel: 617-529-5553 cell Tel: 707-414-0414 Fax: 978-744-7071 [email protected] seen very light use. You owe it to yourself to at least get onboard and see if RABBLE ROUSER is the boat for you. An Addendum section captures many of the changes and the thought process behind them. Measurements Cruising Speed: 9.5 kn Displacement: 61730 Cruising Speed RPM: 2200 lb LOA: 57 ft 7 in Fuel Tanks #: 4 LWL: 54 ft 2 in Fuel Tanks Capacity: 394 gal Beam: 27 ft 9 in Fresh Water Tanks #: 2 Max Bridge Clearance: 90 ft 3 in Fresh Water -

Parts of a Ship: the Basics

Parts of a Ship: The Basics PORT SIDE MAIN FORE MAIN WINDLASS STERN AFT BOW TILLER MAST MAST HATCH HATCH STARBOARD SIDE Overhead view of the schooner Sultana he front of a ship is called the bow, and the back is called the stern. If you were standing T on the ship’s deck looking forward (towards the bow), the left side would be the port side and the right side would be the starboard side. Close to Sultana’s stern is the tiller, a long stick attached to a device called a rudder used for steering the ship. Other important items include the main mast, the fore mast and the windlass (a large simple machine used for pulling up the anchor). POOP DECK QUARTER DECK MIDDLE DECK FORE DECK MAIN TILLER HATCH ultana’s deck is divided into four sections. At the front of the ship is the fore deck, where S the anchors are stored and the fore mast is located. The largest section of the ship is the middle deck where the main hatch is located. Historically, this is where cargo would have been loaded and unloaded. Towards the ship’s stern is the quarter deck. On larger ships, only the high ranking officers were allowed to stand in this area. Sultana’s smallest deck is the poop deck, where sailors steered with the tiller. Parts of a Ship: The Basics NAME: ____________________________________________ DATE: ____________ DIRECTIONS: Use information from the reading to answer each of the following questions in a complete sentence. 1. What is the front of a ship called? What do you call the back end of a ship? 2. -

The Evolution of Decorative Work on English Men-Of-War from the 16

THE EVOLUTION OF DECORATIVE WORK ON ENGLISH MEN-OF-WAR FROM THE 16th TO THE 19th CENTURIES A Thesis by ALISA MICHELE STEERE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2005 Major Subject: Anthropology THE EVOLUTION OF DECORATIVE WORK ON ENGLISH MEN-OF-WAR FROM THE 16th TO THE 19th CENTURIES A Thesis by ALISA MICHELE STEERE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved as to style and content by: C. Wayne Smith James M. Rosenheim (Chair of Committee) (Member) Luis Filipe Vieira de Castro David L. Carlson (Member) (Head of Department) May 2005 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT The Evolution of Decorative Work on English Men-of-War from the 16th to the 19th Centuries. (May 2005) Alisa Michele Steere, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. C. Wayne Smith A mixture of shipbuilding, architecture, and art went into producing the wooden decorative work aboard ships of all nations from around the late 1500s until the advent of steam and the steel ship in the late 19th century. The leading humanists and artists in each country were called upon to draw up the iconographic plan for a ship’s ornamentation and to ensure that the work was done according to the ruler’s instructions. By looking through previous research, admiralty records, archaeological examples, and contemporary ship models, the progression of this maritime art form can be followed. -

SAN FELIPE: Step by Step Pack 2 ™

SAN FELIPE: Step by Step Pack 2 ™ Your parts Stern reinforcement Bulkheads The poop deck Bulkhead planks Planks Tools and equipment Knife File Pencil Wood glue Sandpaper a Using leftover 5 x 5-mm wooden strips, measure and cut beams for Frames 12 and 13. b To identify the bulkheads, mark them with letters A, B and C before removing them. A B C 49 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ c Cut the planks into short lengths and glue them onto the bulkheads. d Cut off the overlapping bulkhead planking and mark the joints with a pencil. e Test-fit bulkhead A below the forecastle deck, aligning it with the outer edge of Frame 4. Trim with a A file if necessary to ease the fit, then glue into place. 50 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ f Glue bulkhead B into place under the stern deck, resting up against the bow side of Frame 9. B g Glue bulkhead C up against Frame 12, making sure that the top of the bulkhead doesn’t extend above the beam. C h Apply glue to the stern reinforcement and place it in the slots of Frame 14, as shown in the photo. 51 SAN FELIPE: Step by Step ™ i Prepare the planks as before and glue them onto the poop deck. When dry, cut off any planking that extends past the edge of the deck. Then mark points to imitate the nails. j Once complete, glue the poop deck in place, resting on top of Frames 12-14. k The photo shows how the assembly should look at this stage. -

Deck Runoff NOD, Phase I Uniform National Discharge Standards For

This document is part of Appendix A, Deck Runoff: Nature of Discharge for the “Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS),” published in April 1999. The reference number is EPA-842-R-99-001. Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS) Appendix A Deck Runoff: Nature of Discharge April 1999 NATURE OF DISCHARGE REPORT Deck Runoff 1.0 INTRODUCTION The National Defense Authorization Act of 1996 amended Section 312 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA)) to require that the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) develop uniform national discharge standards (UNDS) for vessels of the Armed Forces for “...discharges, other than sewage, incidental to normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces, ...” [Section 312(n)(1)]. UNDS is being developed in three phases. The first phase (which this report supports), will determine which discharges will be required to be controlled by marine pollution control devices (MPCDs)—either equipment or management practices. The second phase will develop MPCD performance standards. The final phase will determine the design, construction, installation, and use of MPCDs. A nature of discharge (NOD) report has been prepared for each of the discharges that has been identified as a candidate for regulation under UNDS. The NOD reports were developed based on information obtained from the technical community within the Navy and other branches of the Armed Forces with vessels potentially subject to UNDS, from information available in existing technical reports and documentation, and, when required, from data obtained from discharge samples that were collected under the UNDS program. -

Modifying a SKUD Mkl Gunwale and Reinforcing the Deck August 2010

Modifying a SKUD Mkl gunwale and reinforcing the deck August 2010 Following is a suggested procedure to modify the gunwales of MkI SKUD 18s to more closely resemble the gunwale shape of the MkII boats. Please note this is not a recommended procedure and owners proceeding with the modification do so at their own risk. The early Mkl boats had very little support under the side decks and are very soft. A stiffener was introduced from about boat 019. For these early boats it would be a feasible proposition to modify their gunwales and fit deck beams at the same time. Of these boats, 001 to 009 are particularly light and will benefit most from modification. Boats 010 to 018 will also benefit. Access Sailing Systems has modified hull 033 but used a method (see diagram #2) which left the old flange attached and folded that back on and glassed over it to help maintain a straight and true sheerline. This method requires turning the boat over and is extra work. The method described below (see also diagram #1) is what we would employ if doing another boat. 1. Support the hull in its cradle. 2. Remove the cowling, bow fitting, spin sheet blocks, chain plate fittings. 3. Cut off flange from bow to stern and prop up hull aft if the topsides sag. 4. Mark where deck beams are to be fitted, sand to scuff bonding area. 5. Make deck beams, fit over length deck beams and bond in place with “plexus”. 6. When cured, trim off excess deck beam and trim for new sheerline. -

Glossary of Terms (List Will Be Updated on a Continual Basis)

Glossary of Terms (list will be updated on a continual basis) The words below are new to our Glossary of Terms. These words will be integrated into our overall list, which is below the new words. Chafing Gear – pads, mats, ropes and other materials tied around pieces of rigging to protect them from rubbing on spars and other parts of the rig Foxes – pieces of scrap line made by twisting together several strands or yarns Hand, Reef & Steer – traditional qualifications of an able seaman, to hand is to take in or furl a sail and to reef is to shorten sail and to steer is to take a turn at the helm Helmsman – the Sailor stationed at the ship’s helm (wheel) in charge of steering and keeping a straight course Marline – light, two-stranded line; often tarred and used for seizings Marlinespike – a tapered metal spike used to separate strands of rope, untie knots and as a handle for hauling away on seizings, whippings, etc. Merchant Service – the industry concerned with commercial shipping ventures (i.e., non-military) Rating – denotes a Sailor’s rank, responsibilities and rate of pay (i.e., able seaman, ordinary seaman, boy, etc.) Rigging – the lines and ropes that hold the masts, spars and sails Sail Making – the work of mending, replacing and sewing sails; the sail maker would often advise on how best to set and trim sails Seizing – method of binding two ropes or objects together involving wrapping them tightly with line Splice – weaving together to strands of separate ropes to form one longer rope Watches – division of labor aboard ship; the -

May 14, 2002 PURPOSE: to Inform the Office of Apprenticeship Training, Employer

BULLETIN 2002 06 Date: May 14, 2002 U.S. Department of Labor Distribution: Subject: New Apprenticeable Employment and Training Occupation Able Seaman Administration National Office Office of Apprenticeship All Field Tech Code: 200 Training, Employer and Labor SD+RD+SAC+; Lab.Com Services (OATELS) Washington, D.C. 20210 Symbols: DSNIP/FG Action: Immediate PURPOSE: To inform the Office of Apprenticeship Training, Employer and Labor Services (OATELS), Bureau Apprenticeship and Training (BAT) Staff of a new apprenticeable occupation: Able Seaman RAIS Code: 1043 O*NET Code: 535011.01 Training Term: 2,760 hours Type of Training: Time based BACKGROUND: OATELS’ Division of Standards and National Industry Promotion initiated the apprenticeability request for this occupation. The Able Seaman stands watch at bow or on wing of bridge to look for obstructions in the path of the vessel. He/She turns wheel on bridge or uses emergency steering apparatus to steer vessel as directed by the Mate. The Able Seaman overhauls lifeboats, and lifeboat gear and lowers or raises lifeboats with winch or falls. Other task includes painting and chipping rust on the deck or superstructure of the ship. A Qualified Able Seaman must hold a certificate issued by U.S. Coast Guard. When working aboard vessels carrying liquid cargoes, the Able Seaman must hold a tanker operator’s certificate. An Able Seaman may stow or remove cargo from ship’s hold. Assessment Sheets for Navigational Watch, a suggested work process schedule and related instruction outline are attached for your review. Able Seaman will be added to the list of occupations recognized as apprenticeable by the Office of Apprenticeship Training, Employer and Labor Services when the list is reissued. -

The Boat in the Storm an Interactive Story Based on Mark 4:35–41

Resources for religious education classes Stories of Hope: The Miracles of Jesus The Boat in the Storm An interactive story based on Mark 4:35–41 Materials required: Masking tape; stool; cushion Preparation: Mark the outline of the boat on the floor with tape according to the diagram below. Place the stool and the cushion as indicated. One person should act as narrator. Depending on the size of the class there are two ways of allocating acting roles to the pupils: 1) Jesus, Peter and four other disciples The four disciples act as the oarsmen in the narrative and sit in the positions indicated on the diagram; all other pupils form the outline of the boat. 2) as above but with 7 additional disciples in the boat as indicated on the diagram. The pupils forming the boat should sit or kneel on the outline marked on the floor and either interlock their arms, put their arms around their neighbours’ shoulders, or hold hands so that there are no gaps between them. At the beginning of the story, the 5 or 12 disciples and Jesus stand outside the boat on the ‘shore’. The pupils forming the boat enact the movements marked in italics in the story, and the disciples and Jesus act out the underlined movements appropriate for each character. Diagram: Story: It was evening and the sun was already low on the horizon. The Lake of Galilee was calm with only a few waves making their way lazily to the shore and the surface of the water gleaming with hues of gold and orange. -

2882 Deck Rigging

dskjlaksdjklasjlkasjd NRS Deck Rigging Kit Instructions This deck rigging kit contains the necessary hardware to add bungee lacing to both the bow and stern decks of your kayak. Once installed, this lacing can be used to secure kayak accessories such as bilge pumps, gloves, water bottles, paddle floats, and spare paddles within easy reach. The bungee lacing can be arranged in many ways. Touring kayaks typically have more open deck space in front of the cockpit than behind it. Most bow rigging arrangements have three eyelets on either side, and sometimes an additional eyelet centered at the boat end of the rigging to keep gear from sliding forward. The stern rigging arrangement can either have two or three eyelets on either side, depending on available space, with an optional eyelet centered at the stern end. Kit Includes: • 14 nylon eyelets • 28 stainless bolts • 28 rubber-coated well nuts • 24’ of ¼” bungee cord Additional Items you’ll need: • Pen, Pencil, or Marker • Electric Drill & 3/16” d rill bi t • Phillips-head screwdriver • Aquaseal or silicone sealant (optional) Directions: 1. Determine desired position and configuration for the deck rigging. 2. Place the eyelets in position on the deck and mark each bolt hole location. (Check to ensure the hole placement won’t interfere with existing internal or external kayak hardware.) 3. With 3/16” drill bit, pre-drill each of the bolt holes . 4. Using the included stainless steel bolts, position each of the eyelets on the kayak deck. 5. For extra waterproof security, place a bead of Aquaseal or marine-grade silicone sealant between the eyelet and the hull.