The Evolution of Decorative Work on English Men-Of-War from the 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

An Analytical Approach to the Question of a Clock Change

An Analytical Approach to the Question of a Clock Change by Samuel Halpern One of the ongoing arguments that continues to be brought up is the question of whether or not clocks on Titanic were put back some time before the accident took place Sunday night, April 14, 1912. Some of the deck crew, awakened by the accident at 11:40 p.m. ship’s time, thought that it was close to the time that they were due to take their watch on deck, which would be at 12 o’clock. Despite Boatswain’s Mate Albert Haines, who was awake and on duty at the time, testifying that “The right time, without putting the clock back, was 20 minutes to 12,” there are some that try to argue that a 24 minute clock adjustment had already taken place, and the time of the accident on an unadjusted clock still keeping April 14th time would have been 4 minutes past 12. The underlying question that would resolve this issue is the run time from noon Sunday to the time of the accident. If the run time from noon to the time of the accident was 11 hours 40 minutes, then no clock change had yet taken place, and the time of collision was 11:40 p.m. in unadjusted hours. If the run time was more than 12 hours, then there was a clock change of some 23 or 24 minutes, and the time of collision was 11:40 p.m. in adjusted hours. It really is that simple. So how do we determine the actual run time from the available evidence that does not have to rely on subjective estimates such as time intervals or other measures that people may have perceived? The answer is to take an analytical approach to the problem using the taffrail log mileage data offered by quartermasters George Rowe and Robert Hichens at the inquiries. -

The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1980 The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period Kristin MacLeod Tomlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Kristin MacLeod, "The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period" (1980). Master's Theses. 1921. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1921 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF THE INTRODUCTION OF HEAVY ORDNANCE ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ENGLISH NAVY IN THE EARLY TUDOR PERIOD by K ristin MacLeod Tomlin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1980 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis grew out of a paper prepared for a seminar at the University of Warwick in 1976-77. Since then, many persons have been invaluable in helping me to complete the work. I would like to express my thanks specifically to the personnel of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England, and of the Public Records Office, London, for their help in locating sources. -

Volunteer Manual

Gundalow Company Volunteer Manual Updated Jan 2018 Protecting the Piscataqua Region’s Maritime Heritage and Environment through Education and Action Table of Contents Welcome Organizational Overview General Orientation The Role of Volunteers Volunteer Expectations Operations on the Gundalow Workplace Safety Youth Programs Appendix Welcome aboard! On a rainy day in June, 1982, the replica gundalow CAPTAIN EDWARD H. ADAMS was launched into the Piscataqua River while several hundred people lined the banks to watch this historic event. It took an impressive community effort to build the 70' replica on the grounds of Strawbery Banke Museum, with a group of dedicated shipwrights and volunteers led by local legendary boat builder Bud McIntosh. This event celebrated the hundreds of cargo-carrying gundalows built in the Piscataqua Region starting in 1650. At the same time, it celebrated the 20th-century creation of a unique teaching platform that travelled to Piscataqua region riverfront towns carrying a message that raised awareness of this region's maritime heritage and the environmental threats to our rivers. For just over 25 years, the ADAMS was used as a dock-side attraction so people could learn about the role of gundalows in this region’s economic development as well as hundreds of years of human impact on the estuary. When the Gundalow Company inherited the ADAMS from Strawbery Banke Museum in 2002, the opportunity to build a new gundalow that could sail with students and the public became a priority, and for the next decade, we continued the programs ion the ADAMS while pursuing the vision to build a gundalow that could be more than a dock-side attraction. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12562-8 - Archaeology and the Social History of Ships, 2nd Edition Richard A. Gould Index More information general index Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987, Birka, Sweden, 182–183 343–345 Blackwall Frigates, 304 Actian rams, 144 blockade-runners (Confederate), 265, Aeolian Islands, Italy, 153 269, 271–273, 276–277, 280 Aland˚ Islands, Finland, 178–179, bombardeta cannon, 218–220, 226, 186–187 243 Alexandria, Egypt, 146, 319, 321, 335 Bouguer, Pierre, 75 alternative archaeologies, 354 Boutakov, Admiral Grigorie, 289 amphora, 49, 51, 128–129, 131–132, Braudel, Fernand, 155–156, 173 136, 142, 145–148 Brouwer, Hendrik, 239 Anaconda Plan, 270, 277, 310 buoyancy, center of, 74 archery (at sea), 137, 219, 224–225, Bukit Tengkorak, Borneo, 170 228 bulk cargoes, 4, 76–77, 159, 163, 185, arithmetic mean center (AMC), 39–40 206–207, 248–249 arms race, early modern, 285–286 association, physical Cabot, John, 211 primary, 54, 57–59 Caesarea Maritima, Israel, 320, 329 secondary, 58–60 captain’s walk (see also widow’s walk), tertiary, 60 267 autonomous underwater vehicles caravel, 210, 212–213, 218 (AUVs), 2, 49, 346 caravela latina, 210 caravela redonda, 210 baidarka, 93, 95, 99 cargo-preference trade, 6 Baker, Matthew, 70 carrack, 191, 195, 204, 216, 223, 246 Banda, Indonesia, 239 carvel construction, 191, 200 barratry, 264 Catherine of Aragon, 225 Bass, George F., 2, 20, 26, 50–52, 81, Cederlund, Carl Olof, 54, 61, 234–236 127–128, 130, 155–157, Celtic tradition in shipbuilding, 114 173–174, 176–177 cerbatana cannon, 219 Bayeux Tapestry, 180–181, 207 chaos theory (of underwater Beardman jug, 242 archaeology), 2–3 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12562-8 - Archaeology and the Social History of Ships, 2nd Edition Richard A. -

SEA8 Techrep Mar Arch.Pdf

SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Report prepared by: Maritime Archaeology Ltd Room W1/95 National Oceanography Centre Empress Dock Southampton SO14 3ZH © Maritime Archaeology Ltd In conjunction with: Dr Nic Flemming Sheets Heath, Benwell Road Brookwood, Surrey GU23 OEN This document was produced as part of the UK Department of Trade and Industry's offshore energy Strategic Environmental Assessment programme. The SEA programme is funded and managed by the DTI and coordinated on their behalf by Geotek Ltd and Hartley Anderson Ltd. © Crown Copyright, all rights reserved Document Authorisation Name Position Details Signature/ Initial Date J. Jansen van Project Officer Checked Final Copy J.J.V.R 16 April 07 Rensburg G. Momber Project Specialist Checked Final Copy GM 18 April 07 J. Satchell Project Manager Authorised final J.S 23 April 07 Copy Maritime Archaeology Ltd Project No 1770 2 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Contents I LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................5 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................7 1. NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................8 1.1 -

Gunwale (Canoe Rails) Repair Guide Wood Gunwale Repair

Gunwale (Canoe Rails) Repair Guide Wood Gunwale Repair Canoes with fine woodwork are a tradition at Mad River Canoe. The rails, seats and thwarts on your Mad River Canoe are native Vermont straight-grained ash, chosen for its resiliency, strength and aesthetic appearance. Unlike aluminum or plastic materials, white ash will not kink upon impact and cause undue damage to the canoe hull. There are more options involved in repair of wood gunwales than with vinyl or aluminum, making this section a bit longer than the corresponding instructions for other types of rails. Don't let the length of this document intimidate you - here's an overview of this section to help you plan your repair strategy: General Information - Everyone should read this section. Pre-installation preparation - Everyone should read this section. Gunwale replacement instructions - How to replace both rails of your canoe. Replacing Gunwales with inset decks (including complete deck replacement) - If your canoe has inset decks you will likely have to replace them when you replace your rails. The other option is: Short-splicing method to preserve original inset decks when rerailing - You may cut the existing inwales of your canoe to avoid replacing your existing deck. The new inwale must be carefully spliced to the section of existing inwale. Installation of a 4' splicing section - If you have damage to a small section of gunwale, you can splice in a replacement section on the inside, outside or both. General Information Ordering replacement ash gunwales Rails can be ordered from an authorized Mad River dealer. Replacement ash rails are available for all Mad River Canoes. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Digital 3D Reconstruction of British 74-Gun Ship-Of-The-Line

DIGITAL 3D RECONSTRUCTION OF BRITISH 74-GUN SHIP-OF-THE-LINE, HMS COLOSSUS, FROM ITS ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PLANS A Thesis by MICHAEL KENNETH LEWIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Filipe Castro Committee Members, Chris Dostal Ergun Akleman Head of Department, Darryl De Ruiter May 2021 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2021 Michael Lewis ABSTRACT Virtual reality has created a vast number of solutions for exhibitions and the transfer of knowledge. Space limitations on museum displays and the extensive costs associated with raising and conserving waterlogged archaeological material discourage the development of large projects around the story of a particular shipwreck. There is, however, a way that technology can help overcome the above-mentioned problems and allow museums to provide visitors with information about local, national, and international shipwrecks and their construction. 3D drafting can be used to create 3D models and, in combination with 3D printing, develop exciting learning environments using a shipwreck and its story. This thesis is an attempt at using an 18th century shipwreck and hint at its story and development as a ship type in a particular historical moment, from the conception and construction to its loss, excavation, recording and reconstruction. ii DEDICATION I dedicate my thesis to my family and friends. A special feeling of gratitude to my parents, Ted and Diane Lewis, and to my Aunt, Joan, for all the support that allowed me to follow this childhood dream. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. -

Person Name - Prefix a Table of Salutations That May Precede an Individual’S Name to Identify Social Status

Person Name - Prefix A table of salutations that may precede an individual’s name to identify social status. Accurate and uniform information is key to exchanging data. The table below is the recommended format for an individuals name prefix. Note: Military abbreviations are provided in Non Department of National Defence writing format as per "The Canadian Style, A Guide to Writing and Editing" published in 1997. Prefix Abbreviation Second Lieutenant 2nd Lieut. Acting Sub-Lieutenant Acting Sub-Lieutenant Able Seaman A.B. Abbot Ab. Archbishop Abp. Admiral Admiral Brigadier-General Brig.-Gen Brother Bro. Base Chief Petty Officer BsCPO Captain Capt. Commander Cmdr. Chief Chief Commodore Commodore Colonel Col. Constable Const. Corporal Cpl. Chief Petty Officer 1st class Chief Petty Officer, 1st class Chief Petty Officer 2nd class Chief Petty Officer, 2nd class Constable Cst. Chief Warrant Officer Chief Warrant Officer Doctor Dr. Bishop (Episcopus) Episc Your Excellency Exc. Father Fr. General Gen. Her Worship Her Worship Her Excellency HerEx His Worship His Worship His Excellency HisEx Honourable Hon. Lieutenant-Commander Lt.-Cmdr Lieutenant-Colonel Lt.-Col Lieutenant-General Lt.-Gen Leading Seaman L.S. Lieutenant Lieut. Monsieur M. Person Name - Prefix Prefix Abbreviation Master Ma. Madam Madam Major Maj. Mayor Mayor Master Corporal Master Corporal Major-General Maj.-Gen Miss Miss Mademoiselle Mlle. Madame Mme. Mister Mr. Mistress Mrs. Ms Ms. Master Seaman M.S. Monsignor Msgr. Monsieur Mssr. Master Mstr Master Warrant Officer Master Warrant Officer Naval Cadet Naval Cadet Officer Cadet Officer Cadet Ordinary Seaman O.S. Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 2nd class Petty Officer, 2nd class Professor Prof. -

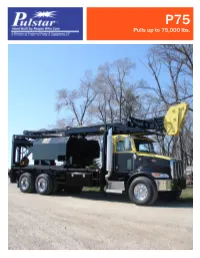

Pulls up to 75,000 Lbs. PULSTAR P75 PULLS up to 75,000 LBS

P75 Pulls up to 75,000 lbs. PULSTAR P75 PULLS UP TO 75,000 LBS. STANDARD FEATURES & SPECIFICATIONS PULLING • 75,000 lbs. hook load accomplished by primary mainline and 6-part traveling block • Roller bearing sheaves • Inner stinger may be fully extended and locked mechanically • Mast is self-supporting and does not require guy cables in most operating conditions (additional tower heights, if selected, have individual load ratings and restrictions) • We provide highly compacted, high-performance wire rope and also provide a tapered roller bearing eye and hook swivel, Pulstar-engineered 6-part traveling block with roller bearing sheaves, and documented certification MAST & MAIN FRAME • Pulstar-engineered and fabricated • Load tested and proven • Documented certification DERRICK ASSEMBLY • Pulstar-engineered rectangular tubing • Alloy tubing incorporated into stinger • (8) elevating and holding hydraulic cylinders incorporated into elevation and holdback • Once in the layback position, we can maintain 475,000 lbs. of holdback automatically, making our derrick truly self-supporting • Documented certification WIRE ROPE • Highly compacted and rotation-resistant • High-performance configuration for state-of-the-art durability • Documented certification PRIMARY MAINLINE • Pulstar-engineered winch drum and drives • Planetary reduction • Failsafe hydraulic disc brakes • Lebus grooving sleeves installed • Heavy hoist option • 2-speed option • Electronic shift on the fly • 6-line traveling block reeved at all times • Eye and hook swivel and high-performance wire rope • Documented certification TAILOUT WINCH • Pulstar-engineered drum and drives • Planetary driven • Hydraulic failsafe brake • Lebus grooving sleeve • 140 FPM bare spool line speed • 8,500 lbs. bare spool pull • High-performance wire rope and swivel hook provided • Documented certification HYDRAULIC SYSTEM • Pressure-compensated, load-sensing pump • Independed stacker control valves • Remotes provided where noted 2 PULSTAR P75 PULLS UP TO 75,000 LBS. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade.