Polyandry Is Extremely Rare in the Firefly Squid, Watasenia Scintillans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning About Our Favourite Squid Species

Cephalopod Science Investigations LEARNING ABOUT OUR FAVOURITE SQUID SPECIES By Cushla Dromgool-Regan Eimear Manning & Anna Quinn www.EXPLORERS.ie The Explorers Education Programme is funded by the Marine Institute Explorers Education Programme engage with primary schools, teachers and children, creating marine leaders and ocean champions. The Explorers Education Programme team provides engaging activities, resources and support for teachers, children and the education network, delivering ocean literacy to primary schools. We aim to inspire children and educators to learn about our marine and maritime identity and heritage, as well as making informed and responsible decisions regarding the ocean and its resources. We communicate about the ocean in a meaningful way, increasing the awareness and understanding of our marine biodiversity, the environment, as well as the opportunities and social benefits of our ocean wealth. To help inspire children learning about the ocean, we have developed a series of teaching materials and resources about Squid! Check out our Explorers books: Cephalopod Science Investigations – Learning about Squid 101; My CSI Squid Workbook. Also, see our interactive film: Cephalopod Science Investigations – Learning about Squid 101 and Dissection. For more information about our Squid series see www.explorers.ie CEPHALOPOD SCIENCE INVESTIGATIONS LEARNING ABOUT OUR FAVOURITE SQUID SPECIES AUTHORS Cushla Dromgool-Regan Eimear Manning Anna Quinn PUBLISHED BY Marine Institute First published in 2021 Marine Institute, Rinville, Oranmore, Galway All or parts of the content of this publication may be reproduced without further permission for education purposes, provided the author and publisher are acknowledged. Authors: Cushla Dromgool-Regan, The Camden Education Trust; Eimear Manning, The Camden Education Trust; & Anna Quinn, Galway Atlantaquaria. -

Bio-Inspired Artificial Helical Chromatophore for Stealth Mode

Bio-inspired Artificial Helical Chromatophore for Stealth Mode Duck Weon Lee Department of Chemistry and Material Science, Aalto University, PO Box 16100, FI-00076 AALTO, Finland Abstract Stealth technology has been very usefully applied in the military fields and is now becoming more prominent as a strategic technology. In nature, the firefly squid can protect itself from enemies using camouflage as a stealth mode. On the other hand, it is able to send fluorescent signals to attract prey by switching into a bright mode. Despite the development of many existing biomimetic materials, there are significant constraints related to their color-changeable velocity and mobility. Herein, we have developed a bio-inspired artificial thermochromic material system, which can reversibly switch between stealth and bright modes and thus provide a means to adapting to one’s environment analogous to the strategy applied by firefly squids. Through vertical contraction, a helically coiled yarn artificial muscle, selectively coated by Rhodamine B and TiO2, can switch between fluorescent and stealth modes with a maximum speed of 0.31 cm/s. Upon external thermal impulse, artificial thermochromic muscle can spin up to 309° and achieve a negative strain of 84.6%. In addition, this research demonstrates thermochromic effects even in underwater aqueous conditions, showing applicability toward underwater robotics. With the cost-effectiveness of the demonstrated system, the developed artificial thermochromic muscles can be implemented into a variety of applications, such as colorimetric sensors and aqueous color-changeable soft robotics. Stealth technology, a type of camouflage, can be used as an antidetection technology to hide aircraft, submarines, satellites, and missiles from sonar, infrared, radar, and other detectors which take advantage of a power and direction of electromagnetic radiation1–3. -

8 Armed Bandits; a Closer Look at Cephalopods an Educator’S Guide to the Program

8 Armed Bandits; A Closer Look at Cephalopods An Educator’s Guide to the Program Grades K-5 Program Description: This program explores the class of mollusk known as cephalopods. Cephalopods are the most intelligent group of mollusk and most of them lack a shell. The name cephalopod means “head-foot” and contains: octopus, squid, cuttlefish and nautilus. The goal of 8-armed bandits is to teach students the characteristics, defense mechanisms, and extreme intelligence of cephalopods. *Before your class visits the Oklahoma Aquarium* This guide contains information and activities for you to use both before and after your visit to the Oklahoma Aquarium. You may want to read stories about cephalopods and their abilities to the students, present information in class, or utilize some of the activities from this booklet. 1 Table of Contents 8 armed bandits abstract 3 Educator Information 4 Vocabulary 5 Internet resources and books 6 PASS/OK Science standards 7-8 Accompanying Activities Build Your Own squid (K-5) 9 How do Squid Defend Themselves? (K-5) 10 Octopus Arms (K-3) 11 Octopus Math (pre-K-K) 12 Camouflage (K-3) 13 Octopus Puppet (K-3) 14 Hidden animals (K-1) 15 Cephalopod color pages (3) (K-5) 16 Cephalopod Magic (4-5) 19 Nautilus (4-5) 20 2 8 Armed Bandits; A Closer Look at Cephalopods: Abstract Cephalopods are a class of mollusk that are highly intelligent and unlike most other mollusk, they generally lack a shell. There are 85,000 different species of mollusk; however cephalopods only contain octopi, squid, cuttlefish and nautilus. -

High Seas Marine Protected Areas PARKS Magazine 15.3

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 15 No 3 HIGH SEAS MARINE PROTECTED AREAS 2005 Vol 15 No 3 HIGH SEAS MARINE PROTECTED AREAS 2005 © 2005 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Parks ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 15 No 3 HIGH SEAS MARINE PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial GRAEME KELLEHER AND KRISTINA M. GJERDE 1 Foreword: high time for High Seas marine protected areas SYLVIA EARLE 3 Protecting earth’s last frontier: why we need a global system of High Seas marine protected area networks DAN LAFFOLEY 5 High Seas marine protected areas on the horizon: legal framework and recent progress KRISTINA M. GJERDE AND GRAEME KELLEHER 11 Improved oceans governance to conserve high seas biodiversity ELIZABETH FOSTER, TIA FLOOD, ALISTAIR GRAHAM AND MARTIN EXEL 19 2005 The economic rationale for marine protected areas in the High Seas PAUL MORLING 24 Pelagic protected areas: the greatest parks challenge of the 21st century ELLIOTT NORSE 32 Challenges of marine protected area development in Antarctica SUSIE GRANT 41 Conservation on the High Seas – drift algae habitat as an open ocean cornerstone ARLO HEMPHILL 48 Conservation and management of vulnerable deep-water ecosystems in areas beyond national jurisdiction: are marine protected areas sufficient? 57 DAVID LEARY Résumés/Resumenes 65 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 15 No 3 HIGH SEAS MARINE PROTECTED AREAS 2005 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme: 15.1. Planning for the Unexpected 15.2. Private Protected Areas 15.3 High Seas Marine Protected Areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as The international journal for protected area managers ISSN: 0960-233X biodiversity conservation and ecologically sustainable development Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Subscribing to Parks of IUCN – the World Conservation Union. -

An Environmental Education & Citizen Science Guide

1 AN ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION & CITIZEN SCIENCE GUIDE TO WESTERN FIREFLIES By Michelle Sagers A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Education: Natural Science and Environmental Education Hamline University St. Paul, Minnesota August 2020 Capstone Facilitator: Kelly Killorn Content Reviewer: Patrick Kelly Peer Reviewer: Krista Andersen 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….3 Interpretive Firefly Walk………………………..………………………………………….....5 Firefly Photos……………………....…………………………………………………………..11 Observation Form………………………...…………………………………………...19 Post Survey……………………………………………………………...……………..21 At Home Curriculum………………………..………………………………………………..23 Suncatcher Craft……………………………………………………………………....24 Lifecycle Wheel……………………………………………………………………......25 Firefly Parts………………………………………………………………………….....28 Flashlight Activities…………………………………………………………………....30 Community Organization Presentations………………………………………………...32 Youth Presentation……………………………………………………………..……...32 Adult Presentation……………………………………………………………………..32 STEM & Community Fair Activities……………………………………………………….34 Simulated Flash Pattern Recording Activity……………………………………..….34 Recording Form……………………………………………………………………......35 Wetland Dilemma’s Activity………………………………………………………..….36 Kindergarten Field Trip Curriculum……………………………………………………....43 Onsite Program………………………………………………………………………...43 3 Classroom Program………………………………………………………………..….50 References………………………………………………………………………………….....56 Introduction This guide -

Compensation for Longitudinal Chromatic Aberration in the Eye of the firefly Squid, Watasenia Scintillans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Vision Research 44 (2004) 2129–2134 www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Compensation for longitudinal chromatic aberration in the eye of the firefly squid, Watasenia scintillans Ronald H.H. Kroger€ *, Anna Gislen Department of Cell and Organism Biology, Lund Vision Group, Zoology Building, Lund University, Helgonava€gen 3, 22362 Lund, Sweden Received 31 October 2003; received in revised form 26 March 2004 Abstract The camera eyes of fishes and cephalopods have come forth by convergent evolution. In a variety of vertebrates capable of color vision, longitudinal chromatic aberration (LCA) of the optical system is corrected for by the exactly tuned longitudinal spherical aberration (LSA) of the crystalline lens. The LSA leads to multiple focal lengths, such that several wavelengths can be focused on the retina. We investigated whether that is also the case in the firefly squid (Watasenia scintillans), a cephalopod species that is likely to have color vision. It was found that the lens of W. scintillans is virtually free of LSA and uncorrected for LCA. However, the eye does not suffer from LCA because of a banked retina. Photoreceptors sensitive to short and long wavelengths are located at appropriate distances from the lens, such that they receive well-focused images. Such a design is an excellent solution for the firefly squid because a large area of the retina is monochromatically organized and it allows for double use of the surface area in the dichromatically organized part of the retina. -

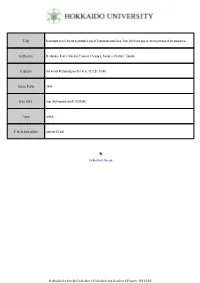

Development of the Ommastrephid Squid Todarodes Pacificus, from Fertilized Egg to the Rhynchoteuthion Paralarva

Title Development of the ommastrephid squid Todarodes pacificus, from fertilized egg to the rhynchoteuthion paralarva Author(s) Watanabe, Kumi; Sakurai, Yasunori; Segawa, Susumu; Okutani, Takashi Citation American Malacological Bulletin, 13(1/2), 73-88 Issue Date 1996 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/35243 Type article File Information sakurai-23.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Development of the ommastrephid squid Todarodes pacific us , from fertilized egg to rhynchoteuthion paralarva Kunli Watanabel , Yasunori Sakurai2, Susumu Segawal , and Takashi Okutani3 lLaboratory of Invertebrate Zoology, Tokyo University of Fisheries, Konan, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108, Japan 2Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University, Minatocho, Hakodate, Hokkaido 041, Japan 3College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University Fujisawa City, Kanagawa 252, Japan Abstract: The present study establishes for the first time an atlas for the normal development of Todarodes pacificus Steenstrup, 1880, from fertilized egg to rhynchoteuthion paralarva. In the course of the study, observations on embryogenesis and histological differentiation in T. pacificus were made for consideration of the developmental mode of the Oegopsida, which is a specialized group with a reduced external yolk sac. It appears that differentiation of the respiratory and digestive organs is relatively delayed in the Oegopsida, with reduction of the yolk sac as well as the egg size. These characters could be related to a reproductive strategy -

Glow in the Dark: Bioluminescence in the Animal and Human World by Elizabeth Kerr, 2020 CTI Fellow Bain Elementary School This

Glow in the Dark: Bioluminescence in the Animal and Human World by Elizabeth Kerr, 2020 CTI Fellow Bain Elementary School This curriculum unit is recommended for: K-2, Science and Literacy Keywords: animals, adaptations, bioluminescence, biomimicry, communication, counter- illumination, aposematism, enzymes Teaching Standards: See Appendix 1 for teaching standards addressed in this unit. Synopsis: This unit will begin an exploration of animals and the adaptations they use to survive, specifically bioluminescence. Students will learn about animals that use bioluminescence and how it is used (communication, aposematism, counter-illumination, aggressive mimicry). Students will begin by studying various types of animals that employ bioluminescence. They will analyze the purpose of bioluminescence in each animal in their environment. The class will then learn about the concept of biomimicry. Students will then use light to create a device for communication across a distance inspired from nature. I plan to teach this unit during the coming year to 16 first grade students in Science and Literacy in the Spring of 2021. This unit will be shared with the other grade level appropriate teachers at my school. I would like the opportunity to teach each class the lab activity in our school science lab if possible. I give permission for Charlotte Teachers Institute to publish my curriculum unit in print and online. I understand that I will be credited as the author of my work. Glow in the Dark: Bioluminescence in the Animal and Human World Elizabeth Kerr Introduction As a teacher of young elementary students, I realized early on the best way to excite students about reading was to integrate reading strategies with science instruction. -

Firefly Squid,'' Watasenia Scintillans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1564 (2002) 189–197 www.bba-direct.com Bioluminescence reaction catalyzed by membrane-bound luciferase in the ‘‘firefly squid,’’ Watasenia scintillans Frederick I. Tsuji* Marine Biology Research Division 0202, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA Received 13 December 2001; received in revised form 11 March 2002; accepted 11 April 2002 Abstract The small Japanese ‘‘firefly squid,’’ Watasenia scintillans, emits a bluish luminescence from dermal photogenic organs distributed along the ventral aspects of the head, mantle, funnel, arms and eyes. The brightest light is emitted by a cluster of three tiny organs located at the tip of each of the fourth pair of arms. Studies of extracts of the arm organs show that the light is due to a luciferin–luciferase reaction in which the luciferase is membrane-bound. The other components of the reaction are coelenterazine disulfate (luciferin), ATP, Mg2+, and molecular oxygen. Based on the results, a reaction scheme is proposed which involves a rapid base/luciferase-catalyzed enolization of the keto group of the C-3 carbon of luciferin, followed by an adenylation of the enol group by ATP. The AMP serves as a recognition moiety for docking the substrate molecule to a luciferase bound to membrane, after which AMP is cleaved and a four-membered dioxetanone intermediate is formed by the addition of molecular oxygen. The intermediate then spontaneously decomposes to yield CO2 and coelenteramide disulfate (oxyluciferin) in the excited state, which serves as the light emitter in the reaction. -

Dynamic Skin Patterns in Cephalopods

How, M. , Norman, M., Finn, J., Chung, W-S., & Marshall, N. J. (2017). Dynamic Skin Patterns in Cephalopods. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, [393]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00393 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.3389/fphys.2017.00393 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Frontiers Media at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2017.00393/full. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 19 June 2017 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00393 Dynamic Skin Patterns in Cephalopods Martin J. How 1*, Mark D. Norman 2 †, Julian Finn 2 †, Wen-Sung Chung 3 and N. Justin Marshall 3 1 Ecology of Vision Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom, 2 Marine Sciences, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 3 Sensory Neurobiology Group, Queensland Brain Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia Cephalopods are unrivaled in the natural world in their ability to alter their visual appearance. These mollusks have evolved a complex system of dermal units under neural, hormonal, and muscular control to produce an astonishing variety of body patterns. -

Cephalopod Guidelines

Reference Resources Caveats from AAALAC’s Council on Accreditation regarding this resource: Guidelines for the Care and Welfare of Cephalopods in Research– A consensus based on an initiative by CephRes, FELASA and the Boyd Group *This reference was adopted by the Council on Accreditation with the following clarification and exceptions: The AAALAC International Council on Accreditation has adopted the “Guidelines for the Care and Welfare of Cephalopods in Research- A consensus based on an initiative by CephRes, FELASA and the Boyd Group” as a Reference Resource with the following two clarifications and one exception: Clarification: The acceptance of these guidelines as a Reference Resource by AAALAC International pertains only to the technical information provided, and not the regulatory stipulations or legal implications (e.g., European Directive 2010/63/EU) presented in this article. AAALAC International considers the information regarding the humane care of cephalopods, including capture, transport, housing, handling, disease detection/ prevention/treatment, survival surgery, husbandry and euthanasia of these sentient and highly intelligent invertebrate marine animals to be appropriate to apply during site visits. Although there are no current regulations or guidelines requiring oversight of the use of invertebrate species in research, teaching or testing in many countries, adhering to the principles of the 3Rs, justifying their use for research, commitment of appropriate resources and institutional oversight (IACUC or equivalent oversight body) is recommended for research activities involving these species. Clarification: Page 13 (4.2, Monitoring water quality) suggests that seawater parameters should be monitored and recorded at least daily, and that recorded information concerning the parameters that are monitored should be stored for at least 5 years. -

Regional Environmental Assessment of the Northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge

Regional Environmental Assessment of the Northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge Document prepared by the Atlantic REMP project to support the ISA Secretariat in facilitating the development of a Regional Environmental Management Plan for the Area in the North Atlantic by the International Seabed Authority Supported by Legal Notice This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein Disclaimer by ISA secretariat: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the International Seabed Authority. Regional Environmental Assessment of the Northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge Authorship The primary authors for each chapter are listed below Geological Overview of the Mid-Atlantic P.P.E. Weaver, Seascape Consultants Ltd Ridge Contract areas and the mining process P.P.E. Weaver, Seascape Consultants Ltd Physical Oceanography of the North Atlantic A.C. Dale, Scottish Association for Marine Science Biology Chapters R. E. Boschen-Rose, Seascape Consultants D.S.M. Billett, Deep Seas Environmental Solutions Ltd A. Colaço, U. Azores D. C. Dunn, Duke University T. Morato, U. Azores I. G. Priede, U. Aberdeen Cumulative impacts D. Jones, NOC D.S.M. Billett, Deep Seas Environmental Solutions Ltd Citation: Weaver, P.P.E., Boschen-Rose, R. E., Dale, A.C., Jones, D.O.B., Billett, D.S.M., Colaço, A., Morato, T., Dunn, D.C., Priede, I.G. 2019. Regional Environmental Assessment of the Northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. 229 pages This document benefitted from the invaluable reviews of Marina Carreiro-Silva, U.