Traces | the UNC-Chapel Hill Journal of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Restricting Hate Speech Against Private Figures: Lessons in Power-Based Censorship from Defamation Law Victor C

Penn State Law eLibrary Journal Articles Faculty Works 2001 Restricting Hate Speech against Private Figures: Lessons in Power-Based Censorship from Defamation Law Victor C. Romero Penn State Law Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/fac_works Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Victor C. Romero, Restricting Hate Speech against Private Figures: Lessons in Power-Based Censorship from Defamation Law, 33 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 1 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTRICTING HATE SPEECH AGAINST "PRIVATE FIGURES": LESSONS IN POWER-BASED CENSORSHIP FROM DEFAMATION LAW by Victor C. Romero* I. THE PROBLEM: THE GROWING, SEAMLESS WEB OF HATE Last fall, the quiet town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania was the scene of a Ku Klux Klan (Klan) rally.! Although the Klan is now but a shadow of its former self,2 the prospect of a Klan rally in the * Professor of Law, The Pennsylvania State University, Dickinson School of Law. E-mail: <[email protected]>. An earlier version of this Article was presented at the Mid-Atlantic People of Color Legal Scholarship Conference in February 2001. Thanks to Marina Angel, David Brennen, Jim Gilchrist, Phoebe Haddon, Christine Jones, Charles Pouncy, Carla Pratt, and Frank Valdes for their thoughtful comments which have greatly improved this piece; Matt Hughson, Gwenn McCollum, and Raphael Sanchez for their expert research assistance; and most of all, my wife, Corie, and my son, Ryan, as well as my family in the Philippines for their constant love and support of this and many other projects. -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

Genetics and Politics in the Soviet Union: Trofim Denisovich Lysenko in the 1930S, Forced Collectivization of Farms in the Soviet Union Reduced Harvests

HGSS: Genetics, Politics, and Society. © 2010, Gregory Carey 1 Genetics, Politics, and Society Eugenics Origins Francis Galton coined the word eugenics in his 1883 book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. The term itself derives from the Greek prefix eu (ευ) meaning good or well and the Greek word genos (γενοσ) meaning race, kind or stock. In 1904, Galton gave a presentation to the Sociological Society in London about eugenics. His presentation, along with invited public commentary, appeared in the American Journal of Sociology (Galton, 1904a) with virtually identical versions (sans commentary) appearing in Nature (Galton, 1904b) and, with commentary, in Sociological Papers (Galton, 1905). In these papers, he defined eugenics as “the science which deals with all influences that improve and develop the inborn qualities of a race.” (It is crucial to recognize that the word “race” was used at that time in an eQuivocal fashion. It could denote the term as we use it today, but it could also refer to a human ethnic group or nationality—e.g., the English race—or even a breed of horse or dog. Galton himself meant it in the generic sense of “stock.”) Galton’s view of the future combined fervor with caution: I see no impossibility in eugenics becoming a religious dogma among mankind, but its details must first be worked out sedulously in the study. Overzeal leading to hasty action would do harm, by holding out expectations of a near golden age, which will certainly be falsified and cause the science to be discredited. By “the study” Galton was referring to academic research. -

Identifying Extreme Racist Beliefs

identifying extreme racist beliefs What to look out for and what to do if you see any extreme right wing beliefs promoted in your neighbourhood. At Irwell Valley Homes, we believe that everyone has the If you see any of these in any of the neighbourhoods right to live of life free from racism and we serve, please contact us straight away on 0300 discrimination. However, whilst we work to promote 561 1111 or [email protected]. We take equality, racism still exists and we want to take action to this extremely seriously and will work with the Greater stop this. Manchester Police to deal with anyone responsible. This guide helps you to identify some of the numbers, signs and symbols used to promote extreme right wing beliefs including racism, extreme nationalism, fascism and neo nazism. 18: The first letter of the alphabet is A; the eighth letter of the alphabet is H. so, 1 plus 8, or 18, equals AH, an abbreviation for Adolf Hitler. Neo-Nazis use 18 in tat- toos and symbols. The number is also used by Combat 18, a violent British neo-Na- zi group that chose its name in honour of Adolf Hitler. 14: This numeral represents the phrase “14 words,” the number of words in an ex- pression that has become the slogan for the white supremacist movement. 28: The number stands for the name “Blood & Honour” because B is the 2nd letter of the alphabet and H is the 8th letter. Blood & Honour is an international neo-Nazi/ racist skinhead group started by British white supremacist and singer Ian Stuart. -

4 Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999

4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999 · Cooperation · Conflict · Human Interest · Shared Experiences Foreword by Hugh Price, President, The National Urban League Introduction by Rabbi Marc Schneier, President, The Foundation For Ethnic Understanding 1 The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding 1 East 93rd Street, Suite 1C, New York, New York 10128 Tel. (917) 492-2538 Fax (917) 492-2560 www.ffeu.org Rabbi Marc Schneier, President Joseph Papp, Founding Chairman Darwin N. Davis, Vice President Stephanie Shnay, Secretary Edward Yardeni, Treasurer Robert J. Cyruli, Counsel Lawrence D. Kopp, Executive Director Meredith A. Flug, Deputy Executive Director Dr. Philip Freedman, Director Of Research Tamika N. Edwards, Researcher The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding began in 1989 as a dream of Rabbi Marc Schneier and the late Joseph Papp committed to the belief that direct, face- to-face dialogue between ethnic communities is the most effective path towards the reduction of bigotry and the promotion of reconciliation and understanding. Research and publication of the 4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States was made possible by a generous grant from Philip Morris Companies. 2 FOREWORD BY HUGH PRICE PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE I am honored to have once again been invited to provide a foreword for The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding's 4th Annual "Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States. Much has happened during 1999 and this year's comprehensive study certainly attests to that fact. I was extremely pleased to learn that a new category “Shared Experiences” has been added to the Report. -

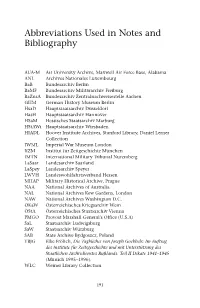

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

"DEADLY MEDICINE: Creating the Master Race"

TAMÁSTSLIKT CULTURAL INSTITUTE "DEADLY MEDICINE: Creating the Master Race" Pendleton, Oregon For immediate release The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s traveling exhibition Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race examines how the Nazi leadership, in collaboration with individuals in professions traditionally charged with healing and the public good, used science to help legitimize persecution, murder, and ultimately, genocide. The exhibition opens at Tamástslikt Cultural Institute on November 11, 2016 and will be on display through January 7, 2017. Opening day is free to the public. “Deadly Medicine explores the Holocaust’s roots in then-contemporary scientific and pseudo-scientific thought,” explains exhibition curator Susan Bachrach. “At the same time, it touches on complex ethical issues we face today, such as how societies acquire and use scientific knowledge and how they balance the rights of the individual with the needs of the larger community.” Eugenics theory sprang from turn-of-the-20th-century scientific beliefs asserting that Charles Darwin’s theories of “survival of the fittest” could be applied to humans. Supporters, spanning the globe and political spectrum, believed that through careful controls on marriage and reproduction, a nation’s genetic health could be improved. The Nazi regime was founded on the conviction that “inferior” races, including the so- called Jewish race, and individuals had to be eliminated from German society so that the fittest “Aryans” could thrive. The Nazi state fully committed itself to implementing a uniquely racist and antisemitic variation of eugenics to “scientifically” build what it considered to be a “superior race.” By the end of World War II, six million Jews had been murdered. -

For Rettssikkerhet Og Trygghet I 200 År. Festskrift Til Justis

For rettssikkerhet og trygghet i 200 år FESTSKRIFT TIL JUSTIS- OG BEREDSKAPSDEPARTEMENTET 1814–2014 REDAKTØR Tine Berg Floater I REDAKSJONEN Stian Stang Christiansen, Marlis Eichholz og Jørgen Hobbel UTGIVER Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet PUBLIKASJONSKODE G-0434-B DESIGN OG OMBREKKING Kord Grafisk Form TRYKK 07 Media AS 11/2014 – opplag 1000 INNHOLD FORORD • 007 • HISTORISKE ORGANISASJONSKART • 008 • PER E. HEM Justisdepartementets historie 1814 – 2014 • 010 • TORLEIF R. HAMRE Grunnlovssmia på Eidsvoll • 086 • OLE KOLSRUD 192 år med justis og politi – og litt til • 102 • HILDE SANDVIK Sivillovbok og kriminallovbok – Justisdepartementets prioritering • 116 • ANE INGVILD STØEN Under tysk okkupasjon • 124 • ASLAK BONDE Går Justisdepartementet mot en dyster fremtid? • 136 • STATSRÅDER 1814–2014 • 144 • For rettssikkerhet og trygghet i 200 år Foto: Frode Sunde FORORD Det er ikke bare grunnloven vi feirer i år. Den bli vel så begivenhetsrike som de 200 som er gått. 07 norske sentraladministrasjonen har også sitt 200- Jeg vil takke alle bidragsyterne og redaksjons- årsjubileum. Justisdepartementet var ett av fem komiteen i departementet. En solid innsats er lagt departementer som ble opprettet i 1814. Retts- ned over lang tid for å gi oss et lesverdig og lærerikt vesen, lov og orden har alltid vært blant statens festskrift i jubileumsåret. viktigste oppgaver. Vi som arbeider i departementet – både embetsverket og politisk ledelse – er med God lesing! på å forvalte en lang tradisjon. Vi har valgt å markere departementets 200 år med flere jubileumsarrangementer gjennom 2014 og med dette festskriftet. Her er det artikler som Anders Anundsen trekker frem spennende begivenheter fra departe- Statsråd mentets lange historie. Det er fascinerende å følge departementets reise gjennom 200 år. -

Teenagers in the Holocaust

Teenagers in the Holocaust When World War II enveloped Europe, children throughout the continent were impacted. Many children were sent to concentration camps while others became part of their country’s Resistance Movements, opposing Nazi orders and policies. Sometimes authors use the story of real children to write historical novels. Sometimes the real stories are as compelling as the fictional ones. Take Shadow on the Mountain, for example. Espen, the main character, is based on Erling Storrusten. Who was he? What role did he play during the war? When Germany invaded Norway, Erling’s country, he decided to fight back. Sixteen at the time of the invasion, in 1940, Erling became a courier for distributing forbidden and illegal underground newspapers. As time went by, and Erling grew older during the war, he took-on more resistance responsibilities. During one key event, he pretended to be who he was not in order to gain entrance into Germany’s headquarters in Lillehammer, Erling’s home town. He was able to draw the layout of the headquarters, then turn that important document over to Resistance leaders. When the German secret police, the Gestapo, learned Erling’s identity, he had to flee Norway. Traveling hundreds of miles over five days, mostly on skis, he reached safety in Sweden. Margi Preus has retold Erling’s story in Shadow on the Mountain. Joan Wolf takes a similar approach in her story Someone Named Eva. Although she doesn’t have a specific character on which to model her heroine, Wolf uses the events of a town called Lidice as the backdrop of her tale. -

United States of America V. Erhard Milch

War Crimes Trials Special List No. 38 Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 1975 Special List No. 38 Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Records of Case II United States of America v. Erhard Milch Compiled by John Mendelsohn National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1975 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data United States. National Archives and Records Service. Nuernberg war crimes trial records. (Special list - National Archives and Records Service; no. 38) Includes index. l. War crime trials--N emberg--Milch case,l946-l947. I. Mendelsohn, John, l928- II. Title. III. Series: United States. National Archives and Records Service. Special list; no.38. Law 34l.6'9 75-6l9033 Foreword The General Services Administration, through the National Archives and Records Service, is· responsible for administering the permanently valuable noncurrent records of the Federal Government. These archival holdings, now amounting to more than I million cubic feet, date from the <;lays of the First Continental Congress and consist of the basic records of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches of our Government. The presidential libraries of Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson contain the papers of those Presidents and of many of their - associates in office. These research resources document significant events in our Nation's history , but most of them are preserved because of their continuing practical use in the ordinary processes of government, for the protection of private rights, and for the research use of scholars and students.