Case 1:04-Cv-00073-LJM-DML Document 827 Filed 10/29/09 Page 1 of 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31295018689751.Pdf (8.512Mb)

^M'-^Ki'm-r- --' •« >i^'?fi O^t LQG The Design for a School of Art 'mi The Depot District Lubbock, Texas Robyn Giuiro^a '^^mX'> m KfiB^i?»5!^ppii|M^|(!f|?s Fall 1999 I^^^S-"* • . .M by Robyn Qulroqa A Thesis Architecture Submitted to the Architecture faculty of the College of Architecture of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment for The Degree of MASTERS OF ARCHITECTURE Jarfcesl White, Dean. College of Architecture December 1999 ii 5 2 a037cQ.L'J> /9 <^ r- •] ^r.^^ wt\' ~^Kitlft ii^ A^^m oj ii N (iW/!>«n#»ij%) 11 J IAB »? s; of IINSSI^ ' 04 THEORY 05 THEORY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES oe BACI^GROUND INFORMATION ON COLLAGE 24 THEORY ISSUES 25 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER ONE 26 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER TWO 27 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER THREE 26 THEORY CASE STUDIES 29 THEORY CASE STUDY NUMBER ONE: THE ANTHENEUM BY RICHARD MEIER THEORY CASE STUDY NUMBER TWO: ADDISON CONFERENCE AND THEATRE CENTRE 33 FACILITY TYPE 34 MISSION STATEMENT 35 ACTIVITY ANALYSIS 37 FACILITY PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS 40 SPATIAL ANALYSIS 56 SPATIAL SUMMARY 60 FACILITY TYPE CASE STUDIES 61 FACILITY TYPE CASE STUDY NUMBER ONE: CENTRE FOR THE VISUAL ARTS BY FRANK GEHRY 67) FAr:il ITY TYPE CASE STUDY NUMBER TWO: ART SCHOOL BY KUOVO & PARTANEN ARCHITECTS 111 OS i|Nii9D^ DESIGN PROCESS SCHEMATIC REVIEW DESIGN DEVELOPMENT COHCEFTONE CONCEPT TWO COHCEFTTHREE DESIGN RESPONSE RESPONSE TO THEORY ISSUES RESPONSE TO FACILITY TYPE PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS RESPONSE TO CONTEXT ISSUES IV -"" IABIH OJ ilNiSSiip 102 DOCUMENTATION 103 Overall Presentation Layout 104 Courtyard Level Plan if: 105 First Floor Plan 106 East and North Elevations 107 West and South Elevations 106 Transverse and Longitudinal Sections 109 Structural Axon 110 Site Plan and Mechanical Flans 111 Interior Perspective 112 Exterior Perspective 113 Mode! Photos 114 Conclusion 115 LIST OF ILLUTRATIONS 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY l£s iHaAgT 'AK I£s fiQABT The theory of artistic collage as an architectural design tool will be used in the design process. -

The Art of Architecture

LEARNING TO LOOK AT ARCHITECTURE LOOK: Allow yourself to take the time to slow down and look carefully. OBSERVE: Observation is an active process, requiring both time and attention. It is here that the viewer begins to build up a mental catalogue of the building’s You spend time in buildings every day. But how often visual elements. do you really look at or think about their design, their details, and the spaces they create? What did the SEE: Looking is a physical act; seeing is a mental process of perception. Seeing involves recognizing or connecting the information the eyes take in architect want you to feel or think once inside the with your previous knowledge and experiences in order to create meaning. structure? Following the steps in TMA’s Art of Seeing Art™* process can help you explore architecture on DESCRIBE: Describing can help you to identify and organize your thoughts about what you have seen. It may be helpful to think of describing as taking a deeper level through close looking. a careful inventory. ANALYZE: Analysis uses the details you identified in your descriptions and LOOK INTERPRET applies reason to make meaning. Once details have been absorbed, you’re ready to analyze what you’re seeing through these four lenses: OBSERVE ANALYZE FORM SYMBOLS IDEAS MEANING SEE DESCRIBE INTERPRET: Interpretation, the final step in the Art of Seeing Art™ process, combines our descriptions and analysis with our previous knowledge and any information we have about the artist and the work—or in this case, * For more information on the Art of Seeing Art and visual literacy, the architect and the building. -

2015 West Coast Championships June 16-20 2015 by 19Turkeys

Volume 26 ~ Issue 6 ~ July 2015 Steve Parsons T/C: 300 Whisper 36 0 24 ML 2015 West Coast Championships Doug Hockinson T/C: 7 TC/U 23 0 15 June 16-20 2015 A T SO CO Notes Marvin Wahl T/C: 357 Mag. 8 0 5 By 19Turkeys U INT T SO CO Notes Russell Mowles XP-100: 7 BR 60 4 40 First and Foremost, a big thank you goes out to those folks that made this match possible. Bret Stuntebeck Rampro: 6.5 BR 60 3 40 Mike & Tyler Abel and Rick Redd worked diligently on Sunday before the match getting the Joe Cullison XP-100: 7 BR 60 2 40 range ready. Mike (Boomer) Aber was ever faithful every day checking guns, and Paul Tyler Abel Rampro: 6 BR 60 1 40 Hoadley was Super Welder keeping us in targets. And a special thanks goes out to Bret Stun- Dan Hagerty XP-100: 6.5 BR 59 0 39 tebeck for being the consummate brew master and fisherman and to Steve Parsons for cook- Russell Plakke T/C: 7 BR 59 0 39 ing the fish and all the shooters & significant others that contributed side dishes and desserts Mike Abel XP-100: 6.5 BR 59 0 39 for the Wednesday night fish fry. Richard Redd T/C: 6 BR 58 0 38 Jim Kesser T/C: 7 TC/U 58 0 38 Also, thanks to all our travelers from around the US, Canada and Australia because we just Steve Parsons XP-100R: 6 B 56 0 37 could not put this match on without the dedication you make coming and supporting us. -

40 Anni Di Memphis in Mostra Al Vitra Design Museum

https://living.corriere.it/tendenze/design/40-anni-di-memphis-in-mostra-al-vitra-design-museum/ 40 anni di Memphis in mostra al Vitra Design Museum Il museo tedesco celebra il gruppo fondato da Ettore Sottsass che ha rivoluzionato l'estetica Anni 80. E influenza ancora generazioni di creativi. Dal 6 febbraio 2021 al 23 gennaio 2022 Testo di Luca Trombetta – Foto Studio Azzurro / Memphis Che stagione formidabile quella del gruppo Memphis. In soli sette anni – dal 1980/81 al 1987, circa – rivoluzionò il modo di vedere e di pensare il design dei decenni successivi e ancora oggi il suo influsso si ritrova nelle collezioni di diversi designer in una sorta di revival Anni 80, tra citazioni nostalgiche e coraggiosi omaggi. Collettivo italiano di design e architettura radunatosi a Milano attorno alla figura magnetica di Ettore Sottsass, Memphis fu l’espressione più alta del movimento Postmoderno in Italia e, con la sua forza dirompente, si affrancò dagli stereotipi del funzionalismo che avevano caratterizzato il design nostrano fino agli Anni 70, ricorrendo a colori sgargianti, forme geometriche, pattern optical, nonché una rilettura ironica e intelligente del kitsch. A quarant’anni dalla sua fondazione, il Vitra Design Museum di Weil am Rhein celebra l’anniversario del gruppo con la mostra Memphis: 40 Years of Kitsch and Elegance curata da Mateo Kries e in calendario dal 6 febbraio 2021 al 23 gennaio 2022. Attraverso una selezione di arredi, lampade, oggetti, disegni, fotografie e materiali d’archivio racconta la portata di una rivoluzione estetica che celebrava il Pop, il banale e il quotidiano e rompeva i tabù del buon gusto e del minimalismo. -

Letter Supporting the Designation of Philip Johnson and John Burgee's

H 20 November 2017 Ms. Meenakshi Srinivasan, Chair New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Municipal Building 1 Centre Street, 9th Floor, North New York, NY 10007 [email protected] Re: Support for designation of Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s AT&T Building, 550 Madison, Avenue, New York, as an individual landmark Dear Ms. Srinivasan, The Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) expresses strong support for the prompt calendaring and designation of the AT&T Building as an individual and interior landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The AT&T Building, designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee, was constructed between 1978 and 1984 and is rightly recognized as a landmark of postmodern American architecture. When completed, it joined Michael Graves’ Portland Municipal Services Building in Portland Oregon (1980-82) as the most visible expressions of postmodern architecture in the United States. The building is significant not only for its iconic Chippendale-inspired pediment, but for the soaring seven- story lobby entered through a distinctive Palladian arch and arcade, which lobby is the subject of the proposed inappropriate alteration. This lobby is of particular significance; of 119 interior landmarks in New York, only eight were completed after 1950. Few publically accessible postmodern interiors survive, and this is undoubtedly one of the finest. We strongly urge the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission to move expeditiously towards Landmarks Commission listing of the AT&T Building, including designation as both an individual and an interior landmark. We believe that Johnson and Burge’s design is of international significance, and the listing of both would insure the preservation of one of the most noteworthy postmodern buildings and interiors produced in the United States. -

Postmodernism and the Theme Park James Marston Fitch

Preservation vs. Historicism: Postmodernism and the Theme Park James Marston Fitch In Selected Writings on Architecture, Preservation and the Built Environment […] It is a romantic proposition to insist that the historic building, once having been saved from the bulldozer, must be preserved in exactly the state in which it was received. It is quite true that any old building, like old artifacts generally, shows signs of all the blows of outrageous fortune to which it has been subjected. And this patina of use may be helpful in reconstructing the actual life-history of the artifact. But they have not necessarily enhanced its artistic integrity. Quite the contrary is too often the case, so that the intentions of the original artist and the client who commissioned the artifact are quite obscured by subsequent interventions in the corpus. This is clearer in a painting than in a building, since our relationship to the one is much simpler and more linear than to the second. In fact, one might say that anything that has happened to a painting since it was first made has altered its artistic integrity. Almost certainly, it will also have been diminished by environmental agents: the chemical action of sunlight, moisture, dust, candle smoke, polluted air; the soaps of cleaners and the waxes of restorers-not to mention well intentioned in-painting by subsequent artists to "improve" it. Thus the modem conservator of painting takes as his task the return of the historic painting as nearly as possible to its original condition. Using the best of modern science and technology, the art conservator undertakes that 1) nothing of the original fabric is to be removed; 2) nothing new is to be added which cannot be justified by rigorous archival and laboratory research which 3) cannot be subsequently removed without damage to the original fabric. -

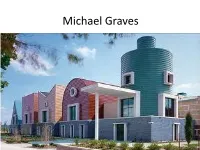

Michael Graves Architect Info

Michael Graves Architect info Michael Graves was born on July 9 1934 in Indianapolis, Indiana. He received his architectural training at the University of Cincinnati doing a program that let him work with Carl A. Strauss (another architect) while getting his education. He entered Harvard University after getting his Bachelor of Science in Architecture in 1958. Architect info (continued) In 1960 he received the Prix de Rome fellowship of the American Academy in Rome. In 1962 he accepted a teaching job at Princeton University. Michael Graves designed the Portland Building in Portland, Ohio, which was an early example of postmodern architecture. How he uses the principles and elements of design in his work: Line because the shapes are made of line. Colour because the buildings are colourful. Contrast because some parts of the building contrast from others. Building style Michael Graves uses many geometric shapes in his work. 5 words I would use to sum up his style are: Postmodern, simple, unique, colorful and playful How he uses shape and dimension to influence the aesthetics of his buildings: Michael Graves uses shape to make his buildings look interesting. Denver Public Library • Michael graves designed a large addition to the Denver public library in 1990. Celebration, Florida Post Office Michael Graves designed the Celebration, Florida Post Office How Michael Graves uses mathematical concepts in his designs He uses a variety of geometric shapes to make up the structure of his buildings. The geometric shapes he uses are symmetrical and most of the finished buildings are as well. There are repeating patterns of 2-D geometric shapes on many of his buildings. -

Ian Volner Michael Graves: Design for Life

Author Q & A Ian Volner, author of Michael Graves: Design for Life A conversation with Ian Volner author of Michael Graves: Design for Life ISBN: 978-1-61689-563-1 6.5 X 9.5 IN / 304 PP / 100 COLOR AND B+W PHOTOGRAPHS $30.00 / HARDCOVER PUBLICATION DATE: OCTOBER 24, 2017 You open your book with Michael’s illness. What was behind that decision? Partially that’s plain old reader-bait: the account of Michael’s illness is so gripping that it helps draw non-architecture people into what’s otherwise a Ian Volner, New York, New York very architecture-y book, and it adds some personal stakes for everything that follows by putting front and center a person undergoing a tremendous ordeal. But from the architectural perspective, it’s also the key inflection point in my whole thesis, which is the most basic question a biography of a designer can ask: “What kind of a designer was this person really, and why was he important?” My case is that Michael was a different kind of architect than a lot of people thought, and his response to his illness revealed that. That’s the moment that alters the way he practiced thereafter, as well as the way his earlier career can be read, and it recasts him as a critical foil to what’s been going on in the built environment in our time. So I wanted it right there in the first chapter. How did Michael, despite having few creative outlets as a child, and little or no encouragement, gravitate toward architecture? He really wasn’t good at much of anything (or at any rate felt himself not to be good at anything) except drawing, which he could do so much better than anyone else. -

John Massengale AIA CNU

John Massengale AIA CNU OHN MASSENGALE has won awards for architecture, urban design, J historic preservation, and architectural history. In all his work—from arranging rooms to making buildings to organizing street plans—John emphasizes the importance of making places where people want to be. A former Board member of the Congress for New Urbanism (CNU) and the Institute for Classical Art & Architecture (ICAA), John was the Founding Chair of CNU New York and CNU NYC. The New York Times called the CNU "the most important phenomenon to emerge in American architecture in the post-Cold War era." John has taught at Notre Dame, the University of Miami, Georgia Tech, the Institute for Classical Art & Architecture, and the Prince's Foundation for the Built Environment, and is a graduate of Harvard College and the University of Pennsylvania. • John was co-author with Victor Dover of Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Towns (Wiley, 2014). John Norquist, former Mayor of Milwaukee, called it "the best book ever written on street design." • John wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Times about lessons from Europe for American streets: "There Are Better Ways To Get Around Town," New York Times, Opinion, May 15, 2018. • Co-Author, with Robert A.M. Stern and Gregory Gilmartin, New York 1900, Metropolitan Architecture & Urbanism, 1890-1915 (Rizzoli, 1983), the first architecture book nominated for a National Book Award. • Winner of the 2019 Seaside Prize: "The Seaside Institute awards the Seaside Prize each year to individuals or organiza- tions who have made significant contributions to the quality and character of our communities." • One of the earliest Town Architects of Seaside, Florida, the first New Urban development. -

N 190044 Him-550 Madison Avenue Landmark

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION September 26, 2018/Calendar No. 18 N 190044 HIM IN THE MATTER OF a communication dated August 10, 2018, from the Executive Director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission regarding the landmark designation of the AT&T Corporate Headquarters Building (Block 1291, Lot 10), by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on July 31, 2018 (Designation List No. 509/LP-2600), Borough of Manhattan, Community District 5. Pursuant to Section 3020.8(b) of the City Charter, the City Planning Commission shall submit to the City Council a report with respect to the relation of any designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, whether a historic district or a landmark, to the Zoning Resolution, projected public improvements, and any plans for the development, growth, improvement or renewal of the area involved. On June 19, 2018, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the AT&T Corporate Headquarters Building as a historical landmark. The landmark designation consists of Block 1291, Lot 10. The landmark site at 550 Madison Avenue fronts on the west side of Madison Avenue between East 56th Street and East 55th Street in the Midtown East neighborhood, Manhattan Community District Five. The AT&T Corporate Headquarters Building (later Sony Plaza, now 550 Madison Avenue) is an icon of the Manhattan skyline and of postmodern architecture. The top of the office tower is crowned by a colossal broken pediment, a feature that sets the building dramatically apart from earlier glass skyscrapers in midtown. Built for the American Telephone and Telegraph Company between 1978 and 1984, the headquarters was designed by architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee, in association with Simmons Architects. -

Elkhart, Culver and Warsaw, James W

Pl a nnerMichiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 4 July — August 2013 IT’S SHOWTIME! MICHMICHIIANAANA’’SS RRIISSIINGNG STARSTAR TOTO BEBE CROWNEDCROWNED ATAT FFIINALE,NALE, AAUGUSTUGUST 22 ATAT 8P8PMM Board of Directors Chair David M. Findlay Vice Chair A Message from Greg Giczi Rodney F. Ganey Ida Reynolds Watson President and GM, WNIT Public Television President and General Manager Greg Giczi Treasurer Kevin J. Morrison Secretary Happy Summer Everyone! Dr. Susan Ohmer I think Michiana is a very special place to be in the summer. We seem to have a little of everything. I Directors love going to Lake Michigan beaches and enjoy the food and music at our summer festivals. Each of Thomas G. Coley, Ph.D. our Michiana communities has its own special personality and charm. Kathryn Demarais Irene E. Eskridge Here at WNIT, your PBS station, we’ve been busy preparing for “Michiana’s Rising Star.” That’s our William A. Gitlin regional talent show which has now completed its audition phase. We started out with over 150 Tracy D. Graham hopeful performers and whittled that list down to about 125. We wanted to have 25 contestants Albert L. Gutierrez at each of our regional judging sites. In Benton Harbor, South Bend, Elkhart, Culver and Warsaw, James W. Hillman our contenders gave it their best before a panel of four judges and our WNIT television cameras. Najeeb A. Khan Five finalists were announced from each location. We are now editing all this footage to produce a Glenn E. Killoren series of “Michiana’s Rising Star” television specials. -

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Confrontation with Postmodernity

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2005-6: Word Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate & Image Research Fellows 4-1-2006 Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Confrontation with Postmodernity Gerard Leone University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons Leone, Gerard, "Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Confrontation with Postmodernity" (2006). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2005-6: Word & Image. 14. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006/14 2005-2006 Penn Humanities Forum on Word & Image, Undergraduate Mellon Research Fellows. URL: http://humanities.sas.upenn.edu/05-06/mellon_uhf.shtml This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Confrontation with Postmodernity Abstract This presentation, like the others of this panel, concerns itself with interactions that take place between those who create a work and those that study it, those who practice and those who theorize, not that they are exclusive characterizations. In the particular case of my project, the interaction between practitioners/ theorists and a critical establishment is an adversarial one, or many times seems that way. My project is titled: Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Confrontation with Postmodernity. The immensity of the material the Venturis have produced and the variety of issues involved in tackling a term like postmodernism makes for many tangents and a far longer paper, what I'm concentrating on in this presentation is the issue which sparked this project: Robert Venturi believes there is a pervasive misconception about his work.