Stanley Drucker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clarinet World

REVIEWS AUDIO NOTES by Kip Franklin Milton Babbit’s Composition for Four undauntedly masters the rapidly cascading Instruments begins with an extended arpeggios in the scherzando section and Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan clarinet passage that Drucker performs conveys control and color in the more of the clarinet world. In addition to his six in an improvisational off-the-cuff lyrical passages. This orchestration is decades with the New York Philharmonic manner. The work features a variety of a refreshing departure from the more (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), instrumental timbres and techniques, traditional clarinet and piano version. his career entails many commissions and resulting in a unique tapestry that Like Nature Moods and Contrasts, recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley resembles the pointillistic writings of Weigl’s New England Suite showcases Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, Webern and Boulez. Valley Weigl’s Nature Drucker’s aptitude as a chamber musician. contains recordings of Drucker playing Moods ensues, with Drucker showcasing Her writing allows each instrument solo many of the most colossal works in the his ability to emulate the human voice. passages while still creating interwoven repertoire, as well as many important and Each of the five movements in this work and complex ensemble textures. Drucker’s rarely-played or obscure smaller works conveys a bucolic ambience with perfectly mellow, deep tone makes this an spanning the entirety of his career. That interwoven counterpoint between the especially memorable piece; at times it Drucker is on display as both a soloist clarinet, voice and violin. The balance in is contemplative and ponderous, and at and chamber musician throughout this this particular work is exceptional, with others jubilant and capricious. -

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, As Posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson Is Clarinetist with the Lightwood Duo, an Actively Touring Clarinet/Guitar Duo

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, as posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson is clarinetist with The Lightwood Duo, an actively touring clarinet/guitar duo. Their CDs are available through their website, http://www.lightwoodduo.com. About two weeks ago, there were some questions about Aage Oxenvad on the list. Having studied Nielsen and clarinet at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen [in 1979], I would like to pass on some first-hand information on Oxenvad. There are two major obstacles to acquiring accurate information about Danish music. First, much of the info exists only in the Danish language; not exactly a familiar language to most. Second, the Danes are not inclined to value the sharing of such information. To quote Tage Scharff, the clarinet professor with whom I studied: "You Americans [and English as well] love to get together and give lectures, deliver papers, and hold conferences. Here in Denmark, vi spiller! [we PLAY]". He was quite amused that I, a performing clarinetist, would be so interested in such material. On a posting on this list, Jarle Brosveet wrote: "In the first place Oxenvad did not inspire Nielsen to write the concerto, although he was the first to perform it. It was written at the request of Nielsen's benefactor and one-time student Carl Johan Michaelsen. Second, Oxenvad, who is described as a choleric, made this unflattering remark about Nielsen and the concerto: "He must be able to play the clarinet himself, otherwise the would hardly have been able to find the worst notes to play." Oxenvad performed it on several occasions with no apparent success although he reportedly did all he could, whatever that is supposed to mean. -

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

John M. Cipolla, Clarinetist Curriculum Vitae 1367 Rolling

John M. Cipolla Curriculum Vitae 1367 Rolling Ridge Way Bowling Green, Kentucky 42013 Office: 270-745-7093, Mobile: 270-996-9270 E-mail: [email protected] Click on this symbol throughout the CV to link to related sites or documents SelectedWorks from the WKU TopSCHOLAR Research and Creative Activity Database EDUCATION The University of North Carolina-Greensboro Greensboro, North Carolina Doctor of Musical Arts in clarinet performance 2002 • Dissertation: Linear Aspects of Harmony in the Countermelodies of New Orleans Jazz Musician, Sidney Bechet • Advisor and major professor, Dr. Kelly Burke The Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey Master of Music in clarinet performance 1987 • Major professor, Dr. George Jones The Eastman School of Music, The University of Rochester Rochester, New York Bachelor of Music in saxophone performance 1984 • Major professors Dr. Ramon Ricker, William Osseck The Juilliard School of Music New York, New York One year of study towards Bachelor of Music in saxophone performance degree 1980 • Scholarship student • Major professor, Joseph Allard ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Professor of Music 2015–present Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Associate Professor of Music 2008–2014 Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Assistant Professor of Music 2002–2008 University of North Carolina at Greensboro Greensboro, North Carolina GTA, Full–Time doctoral student 2000–2002 Wagner College Staten Island, -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Paul Green – Biography

Clarinet Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Contents: Biography Mailing Address: Overview 1000 South Denver Avenue Career Highlights Suite 2104 Tulsa, OK 74119 Reviews Discography Website: Repertoire http://www.pricerubin.com Lectures and Workshops YouTube Links Personal Links Photo Gallery Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Paul Green – Biography Paul Green at 13 in a televised Young People’s Concert with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein, 1962. It has been a love affair that began when Paul Green was only eight years old. The orchestra teacher wanted Paul Green to play the viola, but once the young Paul heard the sound of the clarinet and picked it up in grammar school music class, it was clarinet or nothing. That determination fueled a passion for music and started an adventure that has led him around the world, thrilling audiences in his path, in an unusual career that few can match. Clearly a budding talent, Green began studying privately with the noted clarinet pedagogue Leon Russianoff. Accomplished at age 13, he was recommended to Leonard Bernstein by Stanley Drucker, first clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic. Green was chosen by Leonard Bernstein to be a featured guest in a televised Young People’s Concert with the New York Philharmonic in 1962, performing and recording Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals as a thirteen year old. -

Flute: Late Style in Carl Nielsen’S Works for Flute

THE “ARCADIAN” FLUTE: LATE STYLE IN CARL NIELSEN’S WORKS FOR FLUTE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Beth E. Chandler B.M., Baylor University, 1993 M.M., New England Conservatory, 1996 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Revered as Denmark’s most celebrated musical figure and regarded as one of the finest, albeit under recognized composers, Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) holds a place as one of the most individual and creative artists of his time. Straddling the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and with consideration to the dramatically changing musical climate of that time, Nielsen’s vast output is stylistically complex. His music spans an array of styles, with elements of Romanticism in his early works, to an outright rejection of these same principles and an adoption of extensive progressivism in later works, all the while maintaining features of neoclassicism. There are six known works by Carl Nielsen that include flute in a solo or chamber role. These works date from his late, mature compositional period and include a short piece for solo flute from the incidental music to Aladdin, Op. 34 (1918–19); three pieces from the incidental music to Moderen (The mother), Op. 41 (1920): “Taagen letter” (The fog is lifting) for flute and piano or harp, “Børnene spiller” (The children are playing) for solo flute, and “Tro og håb spiller” (Faith and hope are playing) for flute and viola; the Wind Quintet, Op. -

An Analysis of Sonata Form in Clarinet Concertos by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Louis Spohr, and Carl Maria Von Weber

An Analysis of Sonata Form in Clarinet Concertos by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Louis Spohr, and Carl Maria von Weber A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2012 by Wen-Mi Chen B.M., Peabody Conservatory of Music of The Johns Hopkins University, 2000 M.M., Peabody Conservatory of Music of The Johns Hopkins University, 2003 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Committee Member: Ronald Aufmann, Professor Committee Member: Samuel Ng, Ph.D. Abstract Sonata Theory recognizes five types of sonatas based on their rotational designs. The first movement of most eighteenth-century concertos is classified as a Type 5 sonata (concerto movement) and is the most complicated sonata design due to the great variation that exists among individual Type 5 movements. This document contains a brief introduction to Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory and a summary of the Type 5 sonata. Chapters two, three, and four are extensive studies and analyses of the clarinet concertos composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Louis Spohr, and Carl Maria von Weber. Comprehensive comparisons of these concertos are provided at the end of chapters three and four. Diagrams 2, 3, and 4 are the result of examining these concerto movements. They indicate the sections, zones, and modules of a sonata form in the movements. Appendix A is a list of terms and abbreviations that are used in the analyses. In addition, Hepokoski and Darcy’s Type 5 sonata default settings and options are included in Appendix B. -

Brisbois Ou 0169D 10837.Pdf (847.7Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JEAN FRANÇAIX’S CLARINET CONCERTO: AN EXAMINATION OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICES A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By AARON BRISBOIS Norman, Oklahoma 2012 JEAN FRANÇAIX’S CLARINET CONCERTO: AN EXAMINATION OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICES A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ___________________________ Dr. Valerie Watts, Chair ___________________________ Dr. Suzanne Tirk, Co-Chair ___________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ___________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb ___________________________ Dr. John Fagan © Copyright by AARON BRISBOIS 2012 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude for the help and support I have received for this vast project. Thank you to all of my graduate committee members for your guidance, encouragement, and patience to guide me through the lengthy process of writing this document. Without your help this project could not have been completed with the highest level of quality. Thank you to the late Dr. David Etheridge for helping me improve greatly as a clarinetist, and for encouraging me to move forward with my research of Jean Françaix’s Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra . You are greatly missed. I would like to thank my family for their support also. Thank you to my parents for encouraging me to pursue the study of music. Success in this journey is owing to your emotional, spiritual, and financial support. I would especially like to thank my lovely wife for accompanying me in my recitals and for being a loving, supportive companion. My life would be incomplete without you. -

Philharmonic Hall Lincoln Center for the Pf°Forming Arts

PHILHARMONIC HALL LINCOLN CENTER FOR THE PF°FORMING ARTS 1963-1964 NEW YORK STATE THEATER Designed primarily as a home for ballet and musical One year and seven months after the opening of Philhar theater, under the direction, respectively, of George Balan monic Hall on September 23, 1962, the second unit of chine and Richard Rodgers, the New York State Theater Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts takes its place as also includes public areas of unusual spaciousness and a functioning part of the evolving operational plan. This, utility. Entrance from the plaza level brings one to the by coincidence rather than choice, is the 23rd of April, box office facilities, with corridors to either side from when New York State Day is observed at the World’s which there is access to the orchestra floor of the theater. Fair following formal opening of the Fair the day before. A pair of staircases lead to the Promenade, which faces Governor Nelson D. Rockefeller and other high officials across the plaza to the orchestral level of Philharmonic will be present for the inaugural ceremonies of the New Hall. The Promenade itself, with a floor area of 200 feet York State Theater, in which the two resident companies, by 60 feet, provides bar facilities and ample space for the New York City Ballet and the Music Theater of walking or smoking during intermissions. Each ring above Lincoln Center, will take part. opens on galleries that surround the Promenade on four Though its exterior is designed to be a congruent part sides. The Promenade can also seat 600 or more for of the total Lincoln Center complex and thus balances Philharmonic Hall, which it faces, the interior treatment banquets and other ceremonials. -

Carl Nielsen Alan Gilbert

New York Philharmonic Carl Nielsen Alan Gilbert Violin Concerto; Flute Concerto; Clarinet Concerto Nikolaj Znaider; Robert Langevin; Anthony McGill Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) New York Philharmonic Alan Gilbert, Music Director and Conductor Nikolaj Znaider, violin Robert Langevin, flute Anthony McGill, clarinet Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Concerto for Flute and Orchestra Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 33 (1911–12) 35:08 I Prelude: Largo – Allegro cavallerésco ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������18:43 II Poco adagio – ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6:19 Rondo: Allegretto scherzando ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10:06 Concerto for Flute and Orchestra (1926)��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������18:16 I Allegro moderato������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10:55 II Allegretto, un poco���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

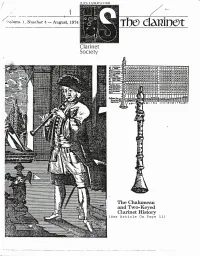

Volume 1, Number 4, August 1974

ii jit;11 icmui idi I 'volume. J, Nurober 4 — August, 1974 Tl)e> da]?in©t Clarinet Society LQEQDQQQ [cnnnnnn □□□□□□□ [ouanuaa ;55d55*" nanna [□3QBQ 1I1B The Chalumeau and Two-Keyed Clarinet History (See Article On Page 11) Page 2 THE CLARINET August, 1974 The International Clarinet The) clarcinot Society Department of Music Idaho State University President, Ramon Kireilis, School of Music, University of Pocatello, Idaho 83209 Denver, Denver, Colo. 80210. Telephone: 208-236-3636 Vice President, Leon Russian off, 12 Pine Ridge Road, (Official magazine of the International Clarinet Society) Greenvale, New York 11548 Secretary-Treasurer, Robert Schott, Department of Music, Editor: Kansas State College of Pittsburg, Kansas 66762 DR. LEE GIBSON Editor, Lee Gibson, School of Music, North Texas State University, Denton, Texas 76203 Publisher: DR. JAMES SCHOEPFLIN Publisher, H. James Schoepflin, Department of Music, Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho 83209 (208) COMMERCIAL ADVERTISING 236-3636) Advertising Manager, Robert Luyben, Luyben Music Co., General Advertising rates: 4318 Main, Kansas City, Mo. 64111 (816) 753-7111 Inside Front Cover: $110.00 Editorial Associates, James Gillespie, (Editor of Reviews), Inside Back Cover 110.00 Department of Music, Northeast Louisiana University, Full Page 90.00 Monroe, La. 71201 Two-thirds Page 66.00 Half-page 50.00 Mary Jungerman, 2030 Spruce, No. 8, Boulder, Colo. 80302 One-third Page 34.00 Bruce Bullock, Amarillo College, 2201 S. Washington, One-fourth Page 25.00 Amarillo, Tex. 79101 One column-inch 6.00 H. James Schoepflin (address above) Richard Gilbert, 201 E. 21st St., No. 15-L, New York, N.Y. A 10% discount will apply for two or more consecutive 10010 entries of the same advertisement.