Returning to Vattel: a Gentlemen's Agreement for the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marshall Court As Institution

Herbert A. Johnson. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall: 1801-1835. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997. xii + 317 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-57003-121-2. Reviewed by Sanford Levinson Published on H-Law (December, 1997) Herbert A. Johnson, who with the late George perhaps the general political atmosphere that L. Haskins co-authored the Holmes Devise volume helped to explain the particular appointments to Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-1815 the Court that made the achievement of Mar‐ (1981), here turns his attention to Marshall's over‐ shall's political and jurisprudential goals easier or all tenure of office. Indeed, the book under review harder. is part of a series, of which Johnson is the general This is a book written for a scholarly audi‐ editor, on "Chief Justiceships of the United States ence, and I dare say that most of its readers will Supreme Court," of which four books have ap‐ already have their own views about such classic peared so far. (The others are William B. Casto on Marshall chestnuts as Marbury v. Madison, Mc‐ Marshall's predecessors Jay and Ellsworth; James Culloch v. Maryland, Gibbons v. Ogden, and the W. Ely, Jr. on Melville W. Fuller; and Melvin I. like. Although Johnson discusses these cases, as he Urofksy on Harlan Fiske Stone and Fred M. Vin‐ must, he does not spend an inordinate amount of son.) One could easily question the value of peri‐ space on them, and the great value of this book odizing the Supreme Court history through its lies in his emphasis on facets of the Court, includ‐ chief justices; but it probably makes more sense ing cases, of which many scholars (or at least I to do so in regard to the formidable Marshall than myself) may not be so aware. -

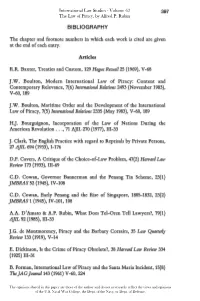

BIBLIOGRAPHY the Chapter and Footnote Numbers in Which Each

397 BIBLIOGRAPHY The chapter and footnote numbers in which each work is cited are given at the end of each entry. Articles R.R. Baxter, Treaties and Custom, 129 Hague Recueil25 (1969), V-68 J.W. Boulton, Modern International Law of Piracy: Content and Contemporary Relevance, 7(6) International Relations 2493 (November 1983), V-60, 189 J.W. Boulton, Maritime Order and the Development of the International Law of Piracy, 7(5) International Relations 2335 (May 1983), V-60, 189 H.J. Bourguignon, Incorporation of the Law of Nations During the American Revolution ..., 71 AJIL 270 (1977), III-33 J. Clark, The English Practice with regard to Reprisals by Private Persons, 27 AJIL 694 (1933), 1-176 D.F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem, 47(2) Harvard Law Review 173 (1933), III-69 C.D. Cowan, Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme, 23(1) JMBRAS 52 (1945), IV-l08 C.D. Cowan, Early Penang and the Rise of Singapore, 1805-1832, 23(2) JMBRAS 1 (1945), IV-l0l, 108 A.A. D'Amato & A.P. Rubin, What Does Tel-Oren Tell Lawyers?, 79(1) AJIL 92 (1985), III-33 J.G. de Montmorency, Piracy and the Barbary Corsairs, 35 Law Quarterly Review 133 (1919), V-14 E. Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harvard Law Review 334 (1925) III-31 B. Forman, International Law of Piracy and the Santa Maria Incident, 15(8) TheJAG Journal 143 (1961) V-60, 224 398 Bibliography L. Gross, Some Observations on the Draft Code ofOffense Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 13 Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 9 (1983) V-235 L. -

The Full Story of United States V. Smith, Americaâ•Žs Most Important

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2012 The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 320 (2012). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. Smith,2 decided by the United * Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Rule of Law Collaborative, University of South Carolina School of Law. -

The Full Story of U.S. V. Smith, America's Most Important Piracy Case

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Law School 2012 The ulF l Story of U.S. v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/law_facpub Part of the International Law Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). This Article is brought to you by the Law School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 | Issue 2 November 2012 The ulF l Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. -

Confronting a Monument: the Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning

The University of New Hampshire Law Review Volume 17 Number 2 Article 12 3-15-2019 Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning Michael S. Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Michael S. Lewis, Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning, 17 U.N.H. L. Rev. 315 (2019). This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of New Hampshire Law Review by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ® Michael S. Lewis Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning 17 U.N.H. L. Rev. 315 (2019) ABSTRACT. The year 2018 brought us two new studies of Chief Justice John Marshall. Together, they provide a platform for discussing Marshall and his role in shaping American law. They also provide a platform for discussing the uses of American history in American law and the value of an historian’s truthful, careful, complete, and accurate accounting of American history, particularly in an area as sensitive as American slavery. One of the books reviewed, Without Precedent, by Professor Joel Richard Paul, provides an account of Chief Justice Marshall that is consistent with the standard narrative. That standard narrative has consistently made a series of unsupported and ahistorical claims about Marshall over the course of two centuries. -

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: the Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P. Curriet In an earlier article I attempted to examine critically the con- stitutional work of the Supreme Court in its first twelve years.' This article begins to apply the same technique to the period of Chief Justice John Marshall. When Marshall was appointed in 1801 the slate was by no means clean; many of our lasting principles of constitutional juris- prudence had been established by his predecessors. This had been done, however, in a rather tentative and unobtrusive manner, through suggestions in the seriatim opinions of individual Justices and through conclusory statements or even silences in brief per curiam announcements. Moreover, the Court had resolved remark- ably few important substantive constitutional questions. It had es- sentially set the stage for John Marshall. Marshall's long tenure divides naturally into three periods. From 1801 until 1810, notwithstanding the explosive decision in Marbury v. Madison,2 the Court was if anything less active in the constitutional field than it had been before Marshall. Only a dozen or so cases with constitutional implications were decided; most of them concerned relatively minor matters of federal jurisdiction; most of the opinions were brief and unambitious. Moreover, the cast of characters was undergoing rather constant change. Of Mar- shall's five original colleagues, William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, and Alfred Moore had all been replaced by 1811.3 From the decision in Fletcher v. Peck4 in 1810 until about 1825, in contrast, the list of constitutional cases contains a succes- t Harry N. -

Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J

UIC Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 Article 3 Fall 2001 Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J. Marshall L. Rev. 75 (2001) Frances Howell Rudko Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Frances Howell Rudko, Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J. Marshall L. Rev. 75 (2001) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol35/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUSE AT THE RUBICON, JOHN MARSHALL AND EMANCIPATION: REPARATIONS IN THE EARLY NATIONAL PERIOD? FRANCES HOWELL RUDKO* Professor D. Kent Newmyer recently attributed Chief Justice John Marshall's record on slavery to a combination of "inherent paternalism" and a deep commitment to commercial interests that translated into racism.1 Newmyer found Marshall's adherence to the law of slavery "painful to observe" and saw it as a product of his Federalism, which required deference to states on the slave is- 2 sue. Marshall's -

Casting Lots: the Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Working Papers Faculty Scholarship 9-9-2005 Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation Daniel M. Filler Drexel University - Thomas R. Kline School of Law, [email protected] Carol Necole Brown University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_working_papers Recommended Citation Daniel M. Filler & Carol N. Brown, Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation, (2005). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_working_papers/29 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA SCHOOL OF LAW Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation Carol Necole Brown 53 Buffalo. L. Rev. 65, Winter 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=800524 Buffalo Law Review Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation Carol Necole Brown 53 BUFF. L. REV. 65 Winter 2005 University at Buffalo Law School BROWN.DOC 9/9/20052/19/2005 9:23 AM5:31:34 PM CASTING LOTS: THE ILLUSION OF JUSTICE AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN PROPERTY ALLOCATION BY CAROL NECOLE BROWN I. Introduction...............................................................................2 II. An Early Case of Casting Lots: A Retrospective on The Antelope Case ..............................................................................9 III. An Analysis of Casting Lots and The Antelope Case..............24 A. -

Piracy Cases in the Supreme Court James J

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 25 Article 2 Issue 4 November-December Winter 1934 Piracy Cases in the Supreme Court James J. Lenoir Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation James J. Lenoir, Piracy Cases in the Supreme Court, 25 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 532 (1934-1935) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. PIRACY CASES IN TBlE SUPREME COURT JAMES J. LENoIR* In ancient times piracy was almost the only maritime undertak- ing of international scope; and, on occasion, even nations participated in acts of a piratical nature. With the development of maritime commerce, however, there was almost a complete reversal of the point of view with which the practice was regarded.' By the latter part of the fifteenth century it was an accepted rule that piracy in any form was contrary to all rules of seafaring trade and that the pirate was thus the common enemy of all nations.' Practically all of the earlier writers accepted this viewpoint, which thereupon be- came an alleged rule of law which judges in most cases accepted and applied.8 In spite of the antiquity of the subject, however, there does not seem to be any acceptable or comprehensive work on piracy., This is all the more to be regretted since piracy as a crime is well worth attention today. -

Slavery, Property, and Marshall in the Positivist Legal Tradition Marc L

Savannah Law Review VOLUME 2 │ NUMBER 1 Slavery, Property, and Marshall in the Positivist Legal Tradition Marc L. Roark* In 1819, a ship called the Columbia departed from Baltimore Harbor with a crew from the United States and flying under Venezuelan colors.1 Shortly after leaving Baltimore, the crew changed the ship’s colors to the Republic of Artega (later known as the Oriental Republic) and changed the ship’s name to the Arraganta.2 The crew then took into its possession enslaved humans from * Associate Professor of Law, Savannah Law School. For their wonderful contribution and engagement in our Colloquium, [Re]Integrating Spaces, I would like to thank: Al Brophy, Anthony Baker, Stephen Clowney, Lia Epperson, Liz Glazer, Angela Harris, Jamila Jefferson-Jones, Adam Kirk, Alberto Lopez, Andrea McArdle, Kali Murray, Connie Pinkerton, Marc Poirier, Amanda Reid, Caprice Roberts, Jeffrey Schmitt, and Andy Wright. I would also like to thank Morgan Cutright for her diligence in bringing this piece to a close. 1 John T. Noonan Jr., The Antelope: The Ordeal of the Recaptured Africans in the Administrations of James Monroe and John Quincy Adams 26-27 (1990). The ship, captained by Admiral Louis Brion, a Venezuelan revolutionary, arrived in Baltimore Harbor carrying only two other sailors. Id. at 27. Jose Artigas, the leader of Uruguay’s Oriental Revolution, sent blank sailor commissions to Admiral Brion with which he recruited Baltimore’s entrepreneurs wishing to engage in the slave trade. Id. Shortly thereafter, approximately thirty sailors swore before a Justice of the Peace that they were not American citizens, after which the Columbia set sail. -

Of Theory and Theodicy: the Problem of Immoral Law* Law and Justice In

Of Theory and Theodicy: The Problem of Immoral Law* Law and Justice in a Multistate World: Essays in Honor of Arthur T. Von Mehren, pp. 473-502 (Symeon C. Symeonides, ed. 2002) Louise Weinberg** I. INTRODUCTION: CRITIQUE AND COUNTER-CRITIQUE Sooner or later even the most impressive theories of adjudication must grapple with the problem of immoral law.1 That problem is to legal theory what the theodicy is to religion. Seriously wrong law cannot be “applied” in some neutral, principled way, as if by holding one’s nose and looking in the other direction. Immoral law invites the condemnation of the world. Yet immoral law, like the poor, will always be with us, even in otherwise highly developed and democratic legal systems. In America we have a rather large legacy of judicial opinions struggling with immoral law—the old cases on slavery. Those cases have intrigued writers2 in American legal and constitutional history,3 as they have writers *Copyright © 2001 by Louise Weinberg. This essay is dedicated to Arthur Taylor von Mehren, whose appreciative student I was at Harvard. It is based in part on a talk I gave at the 1997 annual meeting of the Association of American Law Schools in Washington, D.C., in the Section on Conflict of Laws. An earlier version of this essay, with rather different argumentation and coverage, appears at 56 MD. L. REV. 1316 (1997). I wanted especially to present Professor von Mehren with that paper, as, in the field of the conflict of laws, it is the thing I have written that I liked best. -

Casting Lots: the Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation

Buffalo Law Review Volume 53 Number 1 Article 4 1-1-2005 Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation Carol Necole Brown The University of Alabama School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Carol N. Brown, Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation, 53 Buff. L. Rev. 65 (2005). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol53/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Casting Lots: The Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation CAROL NECOLE BROWNt CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................................... 66 II. An Early Case of Casting Lots: A Retrospective on The Antelope Case ................................................. 74 III. An Analysis of Casting Lots and The Antelope Case ................................................. 88 A. Understanding First- and Second-Order D ecisions ........................................................... 91 B. Understanding The Antelope as Impacted by First- and Second-Order Decisions .................. 95 IV. Achieving Distributive Justice .............................. 99 A. Distributive Justice and Property Law ........... 99 B. The Antelope and Distributive Justice ................ 105 tAssociate Professor of Law, The University of Alabama School of Law. A.B., Duke University, 1991; J.D., Duke University, 1995; LL.M., Duke University, 1995. I would like to thank William S.