Warts and All: How the Plattsburgh Should Change the Way We Look At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship

1 Contents Graphic—Description of a Slave Ship .......................................................................................................... 2 One of the Oldest Institutions and a Permanent Stain on Human History .............................................................. 3 Hostages to America .............................................................................................................................. 4 Human Bondage in Colonial America .......................................................................................................... 5 American Revolution and Pre-Civil War Period Slavery ................................................................................... 6 Cultural Structure of Institutionalized Slavery................................................................................................ 8 Economics of Slavery and Distribution of the Enslaved in America ..................................................................... 10 “Slavery is the Great Test [] of Our Age and Nation” ....................................................................................... 11 Resistors ............................................................................................................................................ 12 Abolitionism ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Defenders of an Inhumane Institution ........................................................................................................ -

Thomas Boyle Settled in Fells' Point Around 1794. Born in Marblehead

Thomas Boyle and Comet 11 Vigilant of Baltimore, 1802 - 1803 Thomas Boyle Thomas Boyle settled in Fells’ Point around 1794. Born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, little is known of his early life, but by age 17 he had earned the confidence of Baltimore merchant John Carrere and commanded several vessels for him, including Vigilant. By 1806 Boyle was regarded as a seasoned commander, and owned several vessels. By 1811, Boyle was fully engaged in the business, civic, and charitable activities of his adopted hometown and was a leader in the Fells’ Point community. On July 11, 1812, Boyle took command of Comet, a privateer schooner built in 1810 by Thomas Kemp. Comet measured 187 tons and 90’6” in length. She mounted ten 12-pounder carronades and 2 ‘long nines.’ With a crew of 110 There are no known images of Comet, but she was men, Boyle headed to sea. similar in size and rig to this unidentified schooner. On July 25,1812 he captured the ship Henry, 400 tons, carrying sugar and wine. Three weeks later he took Hopewell, 346 tons, bound for London with sugar, cotton, coffee, and cocoa. On September 2, Industry was taken, 175 tons and loaded with sugar, molasses, coffee, cocoa and wine. On September 18, Boyle captured the British Letter of Marque John, 372 tons bound for Liverpool with sugar, rum, coffee, cotton, hardwood and copper. Slipping past the British blockade, Comet returned to Baltimore on October 6. The Weekly Register reported: “Comet overhauled every vessel she chased, and took every British vessel she saw, yet made only four prizes . -

White Lies: Human Property and Domestic Slavery Aboard the Slave Ship Creole

Atlantic Studies ISSN: 1478-8810 (Print) 1740-4649 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson To cite this article: Walter Johnson (2008) White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole , Atlantic Studies, 5:2, 237-263, DOI: 10.1080/14788810802149733 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810802149733 Published online: 26 Sep 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 679 View related articles Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 04 June 2017, At: 20:53 Atlantic Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2008, 237Á263 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson* We cannot suppress the slave trade Á it is a natural operation, as old and constant as the ocean. George Fitzhugh It is one thing to manage a company of slaves on a Virginia plantation and quite another to quell an insurrection on the lonely billows of the Atlantic, where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty. Frederick Douglass This paper explores the voyage of the slave ship Creole, which left Virginia in 1841 with a cargo of 135 persons bound for New Orleans. Although the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States was banned from 1808, the expansion of slavery into the American Southwest took the form of forced migration within the United States, or at least beneath the United States’s flag. -

VULCAN HISTORICAL REVIEW Vol

THE VULCAN HISTORICAL REVIEW Vol. 16 • 2012 The Vulcan Historical Review Volume 16 • 2012 ______________________________ Chi Omicron Chapter Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society University of Alabama at Birmingham The Vulcan Historical Review Volume 16 • 2012 Published annually by the Chi Omicron Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta at the University of Alabama at Birmingham 2012 Editorial Staff Executive Editors Beth Hunter and Maya Orr Graphic Designer Jacqueline C. Boohaker Editorial Board Chelsea Baldini Charles Brooks Etheredge Brittany Richards Foust Faculty Advisor Dr. George O. Liber Co-Sponsors The Linney Family Endowment for The Vulcan Historical Review Dr. Carol Z. Garrison, President, UAB Dr. Linda Lucas, Provost, UAB Dr. Suzanne Austin, Vice Provost for Student and Faculty Success, UAB Dr. Bryan Noe, Dean of the Graduate School, UAB Dr. Thomas DiLorenzo, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences, UAB Dr. Rebecca Ann Bach, Associate Dean for Research and Creative Activities in the Humanities and Arts, UAB Dr. Carolyn A. Conley, Chair, Department of History, UAB The Department of History, UAB The Vulcan Historical Review is published annually by the Chi Omicron Chapter (UAB) of Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society. The journal is completely student-written and student-edited by undergraduate and masters level graduate students at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. ©2012 Chi Omicron Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society, the University of Alabama at Birmingham. All rights reserved. No material may be duplicated or quoted without the expressed written permission of the author. The University of Alabama at Birmingham, its departments, and its organizations disclaim any responsibility for statements, either in fact or opinion, made by contributors. -

The Marshall Court As Institution

Herbert A. Johnson. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall: 1801-1835. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997. xii + 317 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-57003-121-2. Reviewed by Sanford Levinson Published on H-Law (December, 1997) Herbert A. Johnson, who with the late George perhaps the general political atmosphere that L. Haskins co-authored the Holmes Devise volume helped to explain the particular appointments to Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-1815 the Court that made the achievement of Mar‐ (1981), here turns his attention to Marshall's over‐ shall's political and jurisprudential goals easier or all tenure of office. Indeed, the book under review harder. is part of a series, of which Johnson is the general This is a book written for a scholarly audi‐ editor, on "Chief Justiceships of the United States ence, and I dare say that most of its readers will Supreme Court," of which four books have ap‐ already have their own views about such classic peared so far. (The others are William B. Casto on Marshall chestnuts as Marbury v. Madison, Mc‐ Marshall's predecessors Jay and Ellsworth; James Culloch v. Maryland, Gibbons v. Ogden, and the W. Ely, Jr. on Melville W. Fuller; and Melvin I. like. Although Johnson discusses these cases, as he Urofksy on Harlan Fiske Stone and Fred M. Vin‐ must, he does not spend an inordinate amount of son.) One could easily question the value of peri‐ space on them, and the great value of this book odizing the Supreme Court history through its lies in his emphasis on facets of the Court, includ‐ chief justices; but it probably makes more sense ing cases, of which many scholars (or at least I to do so in regard to the formidable Marshall than myself) may not be so aware. -

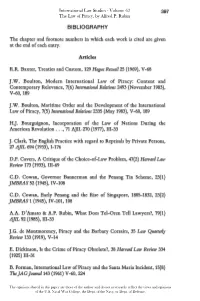

BIBLIOGRAPHY the Chapter and Footnote Numbers in Which Each

397 BIBLIOGRAPHY The chapter and footnote numbers in which each work is cited are given at the end of each entry. Articles R.R. Baxter, Treaties and Custom, 129 Hague Recueil25 (1969), V-68 J.W. Boulton, Modern International Law of Piracy: Content and Contemporary Relevance, 7(6) International Relations 2493 (November 1983), V-60, 189 J.W. Boulton, Maritime Order and the Development of the International Law of Piracy, 7(5) International Relations 2335 (May 1983), V-60, 189 H.J. Bourguignon, Incorporation of the Law of Nations During the American Revolution ..., 71 AJIL 270 (1977), III-33 J. Clark, The English Practice with regard to Reprisals by Private Persons, 27 AJIL 694 (1933), 1-176 D.F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem, 47(2) Harvard Law Review 173 (1933), III-69 C.D. Cowan, Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme, 23(1) JMBRAS 52 (1945), IV-l08 C.D. Cowan, Early Penang and the Rise of Singapore, 1805-1832, 23(2) JMBRAS 1 (1945), IV-l0l, 108 A.A. D'Amato & A.P. Rubin, What Does Tel-Oren Tell Lawyers?, 79(1) AJIL 92 (1985), III-33 J.G. de Montmorency, Piracy and the Barbary Corsairs, 35 Law Quarterly Review 133 (1919), V-14 E. Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harvard Law Review 334 (1925) III-31 B. Forman, International Law of Piracy and the Santa Maria Incident, 15(8) TheJAG Journal 143 (1961) V-60, 224 398 Bibliography L. Gross, Some Observations on the Draft Code ofOffense Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 13 Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 9 (1983) V-235 L. -

Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in Ther 1840S and 1860S Marika Sherwood University of London

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 13 Special Double Issue "Islam & the African American Connection: Article 6 Perspectives New & Old" 1995 Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s Marika Sherwood University of London Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Sherwood, Marika (1995) "Perfidious Albion: Britain, the USA, and Slavery in ther 1840s and 1860s," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 13 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol13/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sherwood: Perfidious Albion Marika Sherwood PERFIDIOUS ALBION: BRITAIN, THE USA, AND SLAVERY IN THE 1840s AND 1860s RITAI N OUTLAWED tradingin slavesin 1807;subsequentlegislation tight ened up the law, and the Royal Navy's cruisers on the West Coast B attempted to prevent the export ofany more enslaved Africans.' From 1808 through the 1860s, Britain also exerted considerable pressure (accompa nied by equally considerable sums of money) on the U.S.A., Brazil, and European countries in the trade to cease their slaving. Subsequently, at the outbreak ofthe American Civil War in 1861, which was at least partly fought over the issue ofthe extension ofslavery, Britain declared her neutrality. Insofar as appearances were concerned, the British government both engaged in a vigorous suppression of the Atlantic slave trade and kept a distance from Confederate rebels during the American Civil War. -

Reflections on the Slave Trade and Impact on Latin American Culture

Unit Title: Reflections on the Slave Trade and Impact on Latin American Culture Author: Colleen Devine Atlanta Charter Middle School 6th grade Humanities 2-week unit Unit Summary: In this mini-unit, students will research and teach each other about European conquest and colonization in Latin America. They will learn about and reflect on the trans- Atlantic slave trade. They will analyze primary source documents from the slave trade by conducting research using the online Slave Voyages Database, reading slave narratives and viewing primary source paintings and photographs. They will reflect on the influence of African culture in Latin America as a result of the slave trade. Finally, they will write a slave perspective narrative, applying their knowledge of all of the above. Established Goals: Georgia Performance Standards: GA SS6H1: The student will describe the impact of European contact on Latin America. a. Describe the encounter and consequences of the conflict between the Spanish and the Aztecs and Incas and the roles of Cortes, Montezuma, Pizarro, and Atahualpa. b. Explain the impact of the Columbian Exchange on Latin America and Europe in terms of the decline of the indigenous population, agricultural change, and the introduction of the horse. GA SS6H2: The student will describe the influence of African slavery on the development of the Americas. Enduring Understandings: Students will be able to describe the impact of European contact on Latin America. Students will be able to define the African slave trade and describe the impact it had on Latin America. Students will reflect on the experiences of slaves in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

The Full Story of United States V. Smith, Americaâ•Žs Most Important

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2012 The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 320 (2012). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. Smith,2 decided by the United * Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Rule of Law Collaborative, University of South Carolina School of Law. -

Papers of the American Slave Trade

Cover: Slaver taking captives. Illustration from the Mary Evans Picture Library. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of the American Slave Trade Series A: Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society Part 2: Selected Collections Editorial Adviser Jay Coughtry Associate Editor Martin Schipper Inventories Prepared by Rick Stattler A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society [microfilm] / editorial adviser, Jay Coughtry. microfilm reels ; 35 mm.(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Contents: pt. 1. Brown family collectionspt. 2. Selected collections. ISBN 1-55655-650-0 (pt. 1).ISBN 1-55655-651-9 (pt. 2) 1. Slave-tradeRhode IslandHistorySources. 2. Slave-trade United StatesHistorySources. 3. Rhode IslandCommerce HistorySources. 4. Brown familyManuscripts. I. Coughtry, Jay. II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Rhode Island Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. VI. Series. [E445.R4] 380.14409745dc21 97-46700 -

Transoceanic Mortality: the Slave Trade in Comparative Perspective

1 Transoceanic Mortality: The Slave Trade in Comparative Perspective by Herbert S. Klein, Stanley L. Engerman, Robin Haines, and Ralph Shlomowitz* Published in the William & Mary Quarterly, LVIII, no. 1 (January 2001), pp. 93-118. Death in the Middle Passage has long been at the center of the moral attack on slavery, and during the past two centuries estimates of the death rate and explanations of its magnitude have been repeatedly discussed and debated. For comparative purposes we draw on studies of mortality in other aspects of the movement of slaves from Africa to the Americas, as well as the experiences of passengers on other long-distance oceanic voyages.1 These comparisons will provide new interpretations as well as raise significant problems for the study of African, European, and American history. The transatlantic slave trade represented a major international movement of persons, and, although only one part of the movement of slaves from the point of enslavement in Africa to their place of forced labor in the Americas, shipboard mortality was its most conspicuous and frequently discussed aspect. Of the more than 27,000 voyages included in the Du Bois Institute dataset, more than 5,000 have information on shipboard mortality. Information is provided on African ports of embarkation; American ports of disembarkation; nationality of carrying vessels; numbers of slaves leaving Africa, arriving in the Americas, and dying in transit; ship size; numbers of crew and their mortality; and length of time at sea. The dataset also permits, with subsequent collecting, the linking of this information to government and private documents containing data on sailing times from Europe to Africa and time on the coast while purchasing slaves.