Casting Lots: the Illusion of Justice and Accountability in Property Allocation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

The Marshall Court As Institution

Herbert A. Johnson. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall: 1801-1835. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997. xii + 317 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-57003-121-2. Reviewed by Sanford Levinson Published on H-Law (December, 1997) Herbert A. Johnson, who with the late George perhaps the general political atmosphere that L. Haskins co-authored the Holmes Devise volume helped to explain the particular appointments to Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-1815 the Court that made the achievement of Mar‐ (1981), here turns his attention to Marshall's over‐ shall's political and jurisprudential goals easier or all tenure of office. Indeed, the book under review harder. is part of a series, of which Johnson is the general This is a book written for a scholarly audi‐ editor, on "Chief Justiceships of the United States ence, and I dare say that most of its readers will Supreme Court," of which four books have ap‐ already have their own views about such classic peared so far. (The others are William B. Casto on Marshall chestnuts as Marbury v. Madison, Mc‐ Marshall's predecessors Jay and Ellsworth; James Culloch v. Maryland, Gibbons v. Ogden, and the W. Ely, Jr. on Melville W. Fuller; and Melvin I. like. Although Johnson discusses these cases, as he Urofksy on Harlan Fiske Stone and Fred M. Vin‐ must, he does not spend an inordinate amount of son.) One could easily question the value of peri‐ space on them, and the great value of this book odizing the Supreme Court history through its lies in his emphasis on facets of the Court, includ‐ chief justices; but it probably makes more sense ing cases, of which many scholars (or at least I to do so in regard to the formidable Marshall than myself) may not be so aware. -

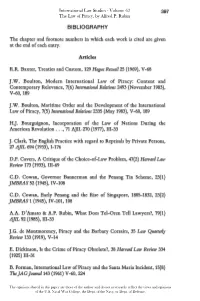

BIBLIOGRAPHY the Chapter and Footnote Numbers in Which Each

397 BIBLIOGRAPHY The chapter and footnote numbers in which each work is cited are given at the end of each entry. Articles R.R. Baxter, Treaties and Custom, 129 Hague Recueil25 (1969), V-68 J.W. Boulton, Modern International Law of Piracy: Content and Contemporary Relevance, 7(6) International Relations 2493 (November 1983), V-60, 189 J.W. Boulton, Maritime Order and the Development of the International Law of Piracy, 7(5) International Relations 2335 (May 1983), V-60, 189 H.J. Bourguignon, Incorporation of the Law of Nations During the American Revolution ..., 71 AJIL 270 (1977), III-33 J. Clark, The English Practice with regard to Reprisals by Private Persons, 27 AJIL 694 (1933), 1-176 D.F. Cavers, A Critique of the Choice-of-Law Problem, 47(2) Harvard Law Review 173 (1933), III-69 C.D. Cowan, Governor Bannerman and the Penang Tin Scheme, 23(1) JMBRAS 52 (1945), IV-l08 C.D. Cowan, Early Penang and the Rise of Singapore, 1805-1832, 23(2) JMBRAS 1 (1945), IV-l0l, 108 A.A. D'Amato & A.P. Rubin, What Does Tel-Oren Tell Lawyers?, 79(1) AJIL 92 (1985), III-33 J.G. de Montmorency, Piracy and the Barbary Corsairs, 35 Law Quarterly Review 133 (1919), V-14 E. Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harvard Law Review 334 (1925) III-31 B. Forman, International Law of Piracy and the Santa Maria Incident, 15(8) TheJAG Journal 143 (1961) V-60, 224 398 Bibliography L. Gross, Some Observations on the Draft Code ofOffense Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 13 Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 9 (1983) V-235 L. -

The Full Story of United States V. Smith, Americaâ•Žs Most Important

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 Issue 2 November 2012 The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 320 (2012). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. Smith,2 decided by the United * Associate Professor, Deputy Director, Rule of Law Collaborative, University of South Carolina School of Law. -

Jul 07 Newsletter.Pub

Victoria Police Four Wheel Drive Club Newsletter Presidents Message July 2007 President's Report - July 2007 Hi Fellow Members, I would like to welcome Craig Triffett, Silvana Tridico, Ben Penrose and Christy Gordon to the club, I am sure you will enjoy being members, especially with a few more trips going onto the trip calendar. Annual General Meeting On the 1st of August is our AGM and the following positions Upcoming Trips: are up for re-election: A.G.M. — 1st August President (must be a Police employee) Treasurer (must be a Police employee) Swap Meet—12th Equipment Officer August Training Coordinator Birdsville Races Trip — Activities Coordinator 26th August — 9th Ordinary Committee Member September Social Sub-Committee Members (number to be determined by AGM) Please think about whether you feel you want to increase your current level of In This Issue contribution to the club, if you do then perhaps a Committee position is the way to do that. President’s Report 1 Training In April and June, the club’s Training Unit conducted Proficiency Driving Your Committee 2 Courses with Paul Kirkbride, Silvana Tridico, Jack Dalrymple, Craig Triffett, Lynette Taylor and Stuart Schulze all qualifying. Congratulations to all of you. From the Editor 3 The Chainsaw Training Course in May had to be cancelled due to insufficient numbers and has been rescheduled for 22-23 September at Warburton. If you Trip Reports 4 interested in attending this course you have to register with Cameron Sanderson, his email address is on the club website. Swap Meet Notice 6 At the moment the Winch Recovery Course in July has two members booked in and the Intermediate Driving Course in August has only one member registered Upcoming Training 9 to attend. -

The Hannay Family by Col. William Vanderpoel Hannay

THE HANNAY FAMILY BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY AUS-RET LIFE MEMBER CLAN HANNAY SOCIETY AND MEMBER OF THE CLAN COUNCIL FOUNDER AND PAST PRESIDENT OF DUTCH SETTLERS SOCIETY OF ALBANY ALBANY COUNTY HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT, 1969, BY COL. WILLIAM VANDERPOEL HANNAY PORTIONS OF THIS WORK MAY BE REPRODUCED UPON REQUEST COMPILER OF THE BABCOCK FAMILY THE BURDICK FAMILY THE CRUICKSHANK FAMILY GENEALOGY OF THE HANNAY FAMILY THE JAYCOX FAMILY THE LA PAUGH FAMILY THE VANDERPOEL FAMILY THE VAN SLYCK FAMILY THE VANWIE FAMILY THE WELCH FAMILY THE WILSEY FAMILY THE JUDGE BRINKMAN PAPERS 3 PREFACE This record of the Hannay Family is a continuance and updating of my first book "Genealogy of the Hannay Family" published in 1913 as a youth of 17. It represents an intensive study, interrupted by World Wars I and II and now since my retirement from the Army, it has been full time. In my first book there were three points of dispair, all of which have now been resolved. (I) The name of the vessel in which Andrew Hannay came to America. (2) Locating the de scendants of the first son James and (3) The names of Andrew's forbears. It contained a record of Andrew Hannay and his de scendants, and information on the various branches in Scotland as found in the publications of the "Scottish Records Society", "Whose Who", "Burk's" and other authorities such as could be located in various libraries. Also brief records of several families of the name that we could not at that time identify. Since then there have been published two books on the family. -

Making Sense of Metaphors: Visuality, Aurality and the Reconfiguration of American Legal Discourse

Pittsburgh University School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications 1994 Making Sense of Metaphors: Visuality, Aurality and the Reconfiguration of American Legal Discourse Bernard J. Hibbitts University of Pittsburgh School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Bernard J. Hibbitts, Making Sense of Metaphors: Visuality, Aurality and the Reconfiguration of American Legal Discourse, 16 Cardozo Law Review 229 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/122 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ARTICLES MAKING SENSE OF METAPHORS: VISUALITY, AURALITY, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF AMERICAN LEGAL DISCOURSE Bernard J.Hibbitts* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: "AN EAR FOR AN EYE" .................... 229 I. METAPHORS IN LIFE AND LAW ........................ 233 II. "MIRRORS OF JUSTICE": VISUALITY AND LEGAL D ISCOURSE ............................................. 238 A . Seeing Culture ..................................... 238 B. Visuality and Power ................................ 264 C. Law and the Phenomenology of Sight ............. 291 III. "FAIR HEARINGS": AURALITY AND THE NEW LEGAL LANGUAGE ............................................ 300 A. Hearing Culture ................................... -

WE Are Very Concerned to Hear That the List of Stewards for the Girls

~~ CONTENTS. opinion it would be far better for all concerned, far more conducive to the ORRESPONDENCE maintainance of Constitutional law, a reasonable interpretation LEADERS "7 C —(Continued)— of the Book Supreme Grand Chapter , 228 Old Kent Lodge of Mark Master Masons 233 of Contitutions, and the safe progress and peaceful developement of our Next Wednesday's Festival : its Chairman, A Temperance Lodge for London 233 and his Province 228 The May Election 233 time-honoured and commendable Craft, if we adhered firmly and Consecration 01 the Henniker Mark Lodge, Charity Voting 233 tenaciously to all that experience has tested, and custom has No. 31S 2-9 Reviews 233 made law. Royal Masonic Institution for Boys 230 Masonic Notes and Queries 233 Hughan 230 #*# Proposed Testimonial to Bro. W.J. R EPORTS OF MASONIC M EETINGS— Field lane Ragged Schools 230 W E are glad to hear that the subscri of the Provincial Grand M.M.M. Craft Masonry 233 ptions for the Building Fund of the Formation Instruction 23:; Lodge of Nottinghamshire 230 Boys' School are increasing. We, however, beg to express our hope that at Oxford 231 Royal Arch 236 The Grand Master Mark Masonry Provincial Priory of North and Hast York- 235 such additions are not made to it in lieu of the normal contributions to the 2 r Ancient and Accepted Rite 236 shire 3 Knights lemplar General Funds of the School. The " rock ahead," according Lodge o£ Benevolence 231 23G to our view, Red Cross of Constantine 236 CORRESPONDENCE— has always been , and we believe the fear is shared in by not a few, that the Mav Elections 23 2 Ohituary 23d attractions of the The Girls' School 232 Consecration of the Camden Chapter, No. -

The Full Story of U.S. V. Smith, America's Most Important Piracy Case

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Law School 2012 The ulF l Story of U.S. v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/law_facpub Part of the International Law Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). This Article is brought to you by the Law School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 1 | Issue 2 November 2012 The ulF l Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case Joel H. Samuels ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Joel H. Samuels, The Full Story of United States v. Smith, America’s Most Important Piracy Case, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int'l Aff. 320 (2012). Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol1/iss2/7 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2012 VOLUME 1 NO. 2 THE FULL STORY OF UNITED STATES V. SMITH, AMERICA’S MOST IMPORTANT PIRACY CASE Joel H. Samuels* INTRODUCTION Many readers would be surprised to learn that a little- explored nineteenth-century piracy case continues to spawn core arguments in modern-day civil cases for damages ranging from environmental degradation in Latin America to apartheid-era investment in South Africa, as well as criminal trials of foreign terrorists.1 That case, United States v. -

Confronting a Monument: the Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning

The University of New Hampshire Law Review Volume 17 Number 2 Article 12 3-15-2019 Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning Michael S. Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Michael S. Lewis, Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning, 17 U.N.H. L. Rev. 315 (2019). This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of New Hampshire Law Review by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ® Michael S. Lewis Confronting a Monument: The Great Chief Justice in an Age of Historical Reckoning 17 U.N.H. L. Rev. 315 (2019) ABSTRACT. The year 2018 brought us two new studies of Chief Justice John Marshall. Together, they provide a platform for discussing Marshall and his role in shaping American law. They also provide a platform for discussing the uses of American history in American law and the value of an historian’s truthful, careful, complete, and accurate accounting of American history, particularly in an area as sensitive as American slavery. One of the books reviewed, Without Precedent, by Professor Joel Richard Paul, provides an account of Chief Justice Marshall that is consistent with the standard narrative. That standard narrative has consistently made a series of unsupported and ahistorical claims about Marshall over the course of two centuries. -

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: the Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P

The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Powers of the Federal Courts, 1801-1835 David P. Curriet In an earlier article I attempted to examine critically the con- stitutional work of the Supreme Court in its first twelve years.' This article begins to apply the same technique to the period of Chief Justice John Marshall. When Marshall was appointed in 1801 the slate was by no means clean; many of our lasting principles of constitutional juris- prudence had been established by his predecessors. This had been done, however, in a rather tentative and unobtrusive manner, through suggestions in the seriatim opinions of individual Justices and through conclusory statements or even silences in brief per curiam announcements. Moreover, the Court had resolved remark- ably few important substantive constitutional questions. It had es- sentially set the stage for John Marshall. Marshall's long tenure divides naturally into three periods. From 1801 until 1810, notwithstanding the explosive decision in Marbury v. Madison,2 the Court was if anything less active in the constitutional field than it had been before Marshall. Only a dozen or so cases with constitutional implications were decided; most of them concerned relatively minor matters of federal jurisdiction; most of the opinions were brief and unambitious. Moreover, the cast of characters was undergoing rather constant change. Of Mar- shall's five original colleagues, William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, and Alfred Moore had all been replaced by 1811.3 From the decision in Fletcher v. Peck4 in 1810 until about 1825, in contrast, the list of constitutional cases contains a succes- t Harry N. -

Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J

UIC Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 Article 3 Fall 2001 Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J. Marshall L. Rev. 75 (2001) Frances Howell Rudko Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Frances Howell Rudko, Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the Early National Period?, 35 J. Marshall L. Rev. 75 (2001) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol35/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUSE AT THE RUBICON, JOHN MARSHALL AND EMANCIPATION: REPARATIONS IN THE EARLY NATIONAL PERIOD? FRANCES HOWELL RUDKO* Professor D. Kent Newmyer recently attributed Chief Justice John Marshall's record on slavery to a combination of "inherent paternalism" and a deep commitment to commercial interests that translated into racism.1 Newmyer found Marshall's adherence to the law of slavery "painful to observe" and saw it as a product of his Federalism, which required deference to states on the slave is- 2 sue. Marshall's