Conscription)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

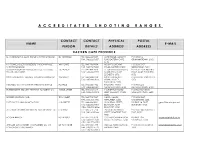

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Crime in the Rural District of Stellenbosch

CRIME IN THE RURAL DISTRICT OF STELLENBOSCH: A CASE STUDY ARLENE JOY DAVIDS Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. SUPERVISOR: PROF. HL ZIETSMAN DECEMBER 2004 SUMMARY One of the most distressing criminal activities has been the attacks on farmers since 1994 and for many years now our farming community has been plagued by these senseless acts of brutality. Since the early nineties there has been a steady increase in the occurrence of farm attacks in our country and the rising incidence of violent crimes on farms and smallholdings in South Africa has become a cause for great concern. The farming community in South Africa has a very significant function in the economy of the country as producers of food and providers of jobs and other commodities required by various other industries, such as the mining industry. They render an indispensable service to our country and therefore we have to ensure that this community receives the necessary safeguarding that is so desperately needed at this time. Farm attacks are occurring at alarming rates in South Africa, the Western Cape, and recently also in the Stellenbosch district. The phenomenon of farm attacks needs to be analysed in the context of the crime situation in general. The underlying reasons for crime are diverse and many, and need to be taken into account when interpreting the causes of crime in South Africa. To ensure that this research endeavour has practical value for the various parties involved in protecting rural communities, crime hotspots and circumstances in which crime occur were identified and used as a tool to provide the necessary protection and mobilisation of forces for these areas. -

Heritage Scan of the Sandile Water Treatment Works Reservoir Construction Site, Keiskammahoek, Eastern Cape Province

HERITAGE SCAN OF THE SANDILE WATER TREATMENT WORKS RESERVOIR CONSTRUCTION SITE, KEISKAMMAHOEK, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE 1. Background and Terms of Reference AGES Eastern Cape is conducting site monitoring for the construction of the Sandile Water Treatment Works Reservoir at British Ridge near Keiskammahoek approximately 30km west of King Williamstown in the Eastern Cape Province. Amatola Water is upgrading the capacity of the Sandile WTW and associated bulk water supply infrastructure, in preparation of supplying the Ndlambe Bulk Water Supply Scheme. Potentially sensitive heritage resources such as a cluster of stone wall structures were recently encountered on the reservoir construction site on a small ridge and the Heritage Unit of Exigo Sustainability was requested to conduct a heritage scan of the site, in order to assess the site and rate potential damage to the heritage resources. The conservation of heritage resources is provided for in the National Environmental Management Act, (Act 107 of 1998) and endorsed by section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA - Act 25 of 1999). The Heritage Scan of the construction site attempted established the location and extent of heritage resources such as archaeological and historical sites and features, graves and places of religious and cultural significance and these resources were then rated according to heritage significance. Ultimately, the Heritage Scan provides recommendations and outlines pertaining to relevant heritage mitigation and management actions in order to limit and -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

Music and Militarisation During the Period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus

Music and Militarisation during the period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus Martha Susanna de Jongh Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Stephanus Muller Co-supervisor: Professor Ian van der Waag December 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 29 July 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In the absence of literature of the kind, this study addresses the role of music in militarising South African society during the time of the South African Border War (1966-1989). The War on the border between Namibia and Angola took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, during which the apartheid South African government believed that it had to protect the last remnants of Western civilization on the African continent against the communist onslaught. Civilians were made aware of this perceived threat through various civilian and military channels, which included the media, education and the private business sector. The involvement of these civilian sectors in the military resulted in the increasing militarisation of South African society through the blurring of boundaries between the civilian and the military. -

Archaeological Assessment Report

CES: PROPOSED UMOYILANGA ANCILLARY INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT ON PORTIONS OF THE FARMS BLAUW BAADJIES VLEY 189 AND FARM 188, CACADU DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: CES Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (AIA) ON PORTIONS OF THE FARMS BLAUW BAADJIES VLEY 189 AND FARM 188 FOR THE PROPOSED UMOYILANGA ANCILLARY INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT, CACADU DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted for: CES Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Caroline Evans (CES) DOCUMENT DISTRIBUTION LIST Name Institution Caroline Evans CES DOCUMENT HISTORY Date Version Status 5 March 2021 1.0 Draft 8 March 2021 2.0 Final Draft 24 June 2021 3.0 Final 3 CES: Umoyilanga Ancillary Infrastructure Development Archaeological Impact Assessment Report DECLARATION I, Nelius Le Roux Kruger, declare that – • I act as the independent specialist; • I am conducting any work and activity relating to the proposed Umoyilanga Ancillary Infrastructure Development Project in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the client; • I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; • I have the required expertise in conducting the specialist report and I will comply with legislation, including the relevant Heritage Legislation (National Heritage Resources Act no. 25 of 1999, Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 as amended, Removal of Graves and -

Designated Service Providers

carecross 2016_Layout 1 2016/07/25 3:48 PM Page 1 DESIGNATED SERVICE PROVIDERS PLATCAP OPTION ONLY carecross 2016_Layout 1 2016/07/25 3:48 PM Page 2 Platinum Health Contact Details Postal address: Private Bag X82081, Rustenburg, 0300 Administration: RPM Hospital, Bleskop, Rustenburg Website: www.platinumhealth.co.za Platinum Health Client Liaison Contact Details Rustenburg Region Northam Tel: 014 591 6600 or 080 000 6942 Client Liaison Supervisor: 081 037 2977 Fax: 014 592 2252 Client Liaison Officer contact number: 083 719 1040 Client Liaison Supervisor: 083 791 1345 [email protected] Client Liaison Officers contact numbers: 083 842 0195 / 060 577 2303 / 060 571 6895 [email protected] Eastern Limb Client Liaison Supervisor: 083 414 6573 Thabazimbi Region Client Liaison Officers contact number: 083 455 7138 & 060 571 0870 (Union, Amandelbult and Thabazimbi) [email protected] Client Liaison Supervisor: 081 037 2977 Client Liaison Officer contact number: 083 795 5981 Eastern Limb Office [email protected] Client Liaison Supervisor: 015 290 2888 Modikwa office Tel: 013 230 2040 Platinum Health Case Management Contact Details Tel: 014 591 6600 or 080 000 6942 After-hours emergencies: 082 800 8727 Fax: 086 247 9497 / 086 233 2406 Email: [email protected] (specialist authorisation) [email protected] (hospital pre-authorisation and authorisation) Platinum Health Contact Guide for Carecross Designated Service Providers Platcap Option only carecross 2016_Layout -

The Journal of the Southern African Jewish Genealogy Special Interest Group

-SU A-SIG U The journal of the Southern African Jewish Genealogy Special Interest Group http://www.jewishgen.org/SAfrica/ Editor: Roy Ogus [email protected] Vol. 14, Issue 3 August 2015 InU this Issue President’s Message – Saul Issroff 2 Editorial – Roy Ogus 3 The African Jews of Yeoville – Ilanit Chernick 4 Isaac Ochberg’s Travels in Eastern Poland – Sir Martin Gilbert 8 New Book – The Girl from Human Street by Roger Cohen 11 Another Brother in my Family – Basil Sandler 12 New Book – Lost and Found in Johannesburg by Mark Gevisser 16 The Baumann Family, Builders of One Kind or Another – Amanda Jermyn 18 Foreigners in South Africa: Rabbis and their Wives Who Brave It Out – Rabbi Izak Rudomin 25 Holiday in the Hinterland – Eve Fairbanks 28 New Book – Exodus to Africa by Adam Yamey 30 The SA-SIG-Sig Newsletter Article Resource: From Siauliai to Stellenbosch – Ann Rabinowitz 31 An Update on the Jewish Life in the Country Communities Project 32 New Items of Interest on the Internet – Roy Ogus 35 Surnames appearing in this Newsletter 44 © 2015 SA-SIG. All articles are copyright and are not to be copied or reprinted without the permission of the author. The contents of the articles contain the opinions of the authors and do not reflect those of the Editor, or of the members of the SA-SIG Board. The Editor has the right to accept or reject any material submitted, or edit as appropriate. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Southern Africa Jewish Genealogy I write this on Yom HaShoah, and feel that it is easy to forget and difficult to take in, the sheer enormity Special Interest Group (SA-SIG) of the Holocaust, an industrialised killing process. -

Dictionary of South African Place Names

DICTIONARY OF SOUTHERN AFRICAN PLACE NAMES P E Raper Head, Onomastic Research Centre, HSRC CONTENTS Preface Abbreviations ix Introduction 1. Standardization of place names 1.1 Background 1.2 International standardization 1.3 National standardization 1.3.1 The National Place Names Committee 1.3.2 Principles and guidelines 1.3.2.1 General suggestions 1.3.2.2 Spelling and form A Afrikaans place names B Dutch place names C English place names D Dual forms E Khoekhoen place names F Place names from African languages 2. Structure of place names 3. Meanings of place names 3.1 Conceptual, descriptive or lexical meaning 3.2 Grammatical meaning 3.3 Connotative or pragmatic meaning 4. Reference of place names 5. Syntax of place names Dictionary Place Names Bibliography PREFACE Onomastics, or the study of names, has of late been enjoying a greater measure of attention all over the world. Nearly fifty years ago the International Committee of Onomastic Sciences (ICOS) came into being. This body has held fifteen triennial international congresses to date, the most recent being in Leipzig in 1984. With its headquarters in Louvain, Belgium, it publishes a bibliographical and information periodical, Onoma, an indispensable aid to researchers. Since 1967 the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) has provided for co-ordination and liaison between countries to further the standardization of geographical names. To date eleven working sessions and four international conferences have been held. In most countries of the world there are institutes and centres for onomastic research, official bodies for the national standardization of place names, and names societies. -

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa: 1963

A Survey of race relations in South Africa: 1963 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOO19640100.042.000 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org A Survey of race relations in South Africa: 1963 Author/Creator Horrell, Muriel Contributor Draper, Mary Publisher South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg Date 1964-01-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1963 Description A survey of race relations in South Africa in 1963 and includes chapters on: Policies and attitudes; New non-White organizations and their activities; Political refugees and absentees; Control of publications; The Population of South Africa, and measures to deter intermingling; The African reserves; Other African areas; Other Coloured and Asian affairs; Employment; Education; Health; Nutrition; Welfare; Recreation; Liquor; Justice; Foreign affairs. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME FOUR Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/866988/ The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Revd Khoza Mgogo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/866988/ I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 7 Foreword and Context of INSTITUTIONAL HEARING: Institutional and Special Hearings..... 1 Prisons ................................................................... 199 Appendix: Submissions to the Commission.. 5 Appendix: Deaths in Detention ........................ 220 Chapter 2 Chapter 8 INSTITUTIONAL HEARING: SPECIAL HEARING: Business and Labour ................................... 18 Compulsory Military Service .................. 222 Appendix 1: Structure of the SADF ............... 247 Chapter 3 Appendix 2: Personnel......................................... 248 INSTITUTIONAL HEARING: Appendix 3: Requirements ................................ 248 The Faith Community .................................. 59 Appendix 4: Legislation ...................................... 249 Chapter 4 Chapter 9 INSTITUTIONAL HEARING: SPECIAL HEARING: The Legal Community ................................ -

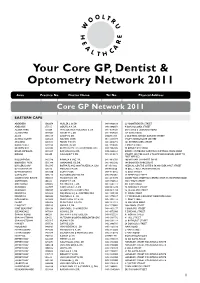

Your Core GP, Dentist & Optometry Network 20

YourCore Core GP Network GP, Dentist 2007 & Optometry Network 2011 Area Practice No. Doctor Name Tel No. Physical Address Core GP Network 2011 EASTERN CAPE ABERDEEN 1582054 MULLer L O, DR 049 8460618 22 VOORTREKKER STREET ADELAIDE 275115 ODUFU A A, Dr 046 6840073 4 BON ACCORD STREET ALGOA PARK 161608 Van Der WestHUIZen D E, DR 041 4564601 CNR DYKE & LEONARD ROAD ALGOAPARK 1539205 Swart M L, DR 041 4564601 125 DYKE ROAD ALICE 1536117 ANJUm N, DR 0406531314 2 OLD TEBA OFFICE, GARDEN STREET ALIWAL NORTH 1465643 NAUde J D, DR 051 6333777 SHOP 5 BRIDGEGATE CENTRE ARCADIA 1458531 ParUk M E, DR 041 4814792 106 ESTERHUIZEN STREET BARKLY EAST 1429124 OLivier J B, DR 045 9710285 5 SMITH STREET BEACON BAY 1458302 BratHwaite H A & Partners, Drs 043 7486502 78 BONZA BAY ROAD BISHO, DIMBAZA 1513869 RamJan A R H, DR 040 6262261 ROOM 1, DIMBAZA SHOPPING COMPLEX, MAIN ROAD BIZANA 145440 NkaLane Y P, DR 039 2510171 STEADY CENTRE SHOP 4, THOMPSON AVENUE, (NEXT TO POST OFFICE) BLOOMENDAL 1462598 Bawasa K inc, DR 041 4816701 180 WILLIAM SLAMMERT DRIVE BOOYSENS PARK 1511394 Sonavane S D, DR 041 4831242 184 BOOYSEN PARK DRIVE BURGERSDORP 1532545 BotHa F J and OostHUIZen J A , Drs 0516531862 MEDICAL CENTRE, SUITE B 50, VAN DER WALT STREET BUTTERWORTH 123110 MbaLana M, DR 0474910520 18 BELL STREET, FASHION HOUSE BUTTERWORTH 1539280 EJUMU M, DR 047 4910762 16 DALY STREET CATHCART 1545213 RicHardson M W, DR 045 8431052 37 HEMMING STREET CLEARY PARK ESTATE 1508865 Hoosen J K, DR 041 4818770 CLEARY PARK SHOPPING CENTRE, SHOP 85, STANFORD ROAD COFIMVABA 208434 Dyantyi