Here Must Be Ways to Ensure That Historical Research Is Made Relevant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

The Interaction Between the Missionaries of the Cape

THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THE MISSIONARIES OF THE CAPE EASTERN FRONTIER AND THE COLONIAL AUTHORITIES IN THE ERA OF SIR GEORGE GREY, 1854 - 1861. Constance Gail Weldon Pietermaritzburg, December 1984* Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Natal, 1984. CONTENTS Page Abstract i List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Sir George Grey and his ’civili zing mission’ 16 Chapter 3 The missionaries and Grey 1854-6 55 Chapter 4 The Cattle Killing 1856/7 99 Chanter 5 The Aftermath of the Cattle Killing (till 1860s) 137 Chapter 6 Conclusion 174 Appendix A Principal mission stations on the frontier 227 Appendix B Wesleyan Methodist and Church of Scotland Missionaries 228 Appendix C List of magistrates and chiefs 229 Appendix D Biographical Notes 230 Select Bibliography 233 List of photographs and maps Between pages 1. Sir George Grey - Governor 15/16 2. Map showing Cape eastern frontier and principal military posts 32/33 3. Map showing the principal frontier mission stations 54/55 4. Photographs showing Lovedale trade departments 78/79 5. Map showing British Kaffraria and principal chiefs 98/99 6. Sir George Grey - 'Romantic Imperialist' 143/144 7. Sir George Grey - civilian 225/226 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge with thanks the financial assistance rendered by the Human Sciences Research Council towards the costs of this research. Opinions expressed or conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not to be regarded as those of the Human Sciences Research Council. -

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

A Classification of the Subtropical Transitional Thicket in the Eastern Cape, Based on Syntaxonomic and Structural Attributes

S. Afr. J. Bot., 1987, 53(5): 329 - 340 329 A classification of the subtropical transitional thicket in the eastern Cape, based on syntaxonomic and structural attributes D.A. Everard Department of Plant Sciences, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6140 Republic of South Africa Accepted 11 June 1987 Subtropical transitional thicket, traditionally known as valley bushveld, covers a significant proportion of the eastern Cape. This paper attempts to classify the subtropical transitional thicket into syntaxonomic and structural units and relate it to other thicket types on a continental basis. Twelve sites along a rainfall gradient were sampled for floristic and structural attributes. The floristic data were classified using TWINSPAN. Results indicate that the class subtropical transitional thicket has at least two orders of vegetation, namely kaffrarian thicket and kaffrarian succulent thicket. Two forms of thicket were recognized for both these orders viz. mesic kaffrarian thicket and xeric kaffrarian thicket for the kaffrarian thicket and mesic succulent thicket and xeric succulent thicket for the kaffrarian succulent thicket. Ordination of site data by DECORANA grouped sites according to these vegetation categories and in a sequence along axis 1 to which the rainfall gradient can be clearly related. Variation within the mesic kaffrarian thicket was however greater than between some of the other thicket types, indicating that more data are required before these forms of thicket can be formalized. Composition, endemism, diversity and the environmental controls on the distribution of the thicket types are discussed. 'n Aansienlike gedeelte van die Oos-Kaap word beslaan deur subtropiese oorgangsruigte, wat tradisioneel as valleibosveld bekend is. Hierdie studie is 'n poging om subtropiese oorgangsruigte in sintaksonomiese en strukturele eenhede te klassifiseer en dit op 'n kontinentale basis in verband met ander ruigtetipes te bring. -

The Valuation of Changes to Estuary Services in South Africa As a Result of Changes to Freshwater Inflow

THE VALUATION OF CHANGES TO ESTUARY SERVICES IN SOUTH AFRICA AS A RESULT OF CHANGES TO FRESHWATER INFLOW BY SG HOSKING, TH WOOLDRIDGE, G D1MOPOULOS, M MLANGENI, C-H LIN, M SALE AND M DU PREEZ DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND ECONOMIC HISTORY AND DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY/ UNIVERSITY OF PORT ELIZABETH REPORT TO THE WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION WRC REPORT NO: 1304/1/04 ISBN NO: 1-77005-278-X DECEMBER 2004 II DISCLAIMER This report emanates from a project financed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research in this report emanated from a project funded by the Water Research Commission and entitled: "THE VALUATION OF CHANGES TO ESTUARY SERVICES IN SOUTH AFRICA AS A RESULT OF CHANGES TO FRESHWATER INFLOW" The authors contributed in the following sections: T Wooidridge - Chapters One and Five G Dimopoulos - Chapters One, Three, Five and Six C-H Lin - Chapters Four and Seven M Sale - Chapters Two, Five and Six S Hosking - all Chapters M du Preez assisted S Hosking with the editorial work M Mlangeni - Chapters Five and Six. The Steering Committee responsible for this project consisted of the following persons: Dr GR Backeberg Water Research Commission (Chairman) Dr SA Mitchell Water Research Commission Dr J Turpie University of Cape Town Mr A Leiman University of Cape Town Prof MF Viljoen University of the Free State Dr J Adams University of Port Elizabeth Dr M du Preez University of Port Elizabeth The funding of the project by the Water Research Commission and the contribution of the members of the Steering Committee is gratefully acknowledged. -

The Third War of Dispossession and Resistance in the Cape of Good Hope Colony, 1799–1803

54 “THE WAR TOOK ITS ORIGINS IN A MISTAKE”: THE THIRD WAR OF DISPOSSESSION AND RESISTANCE IN THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE COLONY, 1799–1803 Denver Webb, University of Fort Hare1 Abstract The early colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland, such as the 1799–1803 war, have not received as much attention from military historians as the later wars. This is unexpected since this lengthy conflict was the first time the British army fought indigenous people in southern Africa. This article revisits the 1799–1803 war, examines the surprisingly fluid and convoluted alignments of participants on either side, and analyses how the British became embroiled in a conflict for which they were unprepared and for which they had little appetite. It explores the micro narrative of why the British shifted from military action against rebellious Boers to fighting the Khoikhoi and Xhosa. It argues that in 1799, the British stumbled into war through a miscalculation – a mistake which was to have far-reaching consequences on the Cape’s eastern frontier and in western Xhosaland for over a century. Introduction The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial wars on the Cape Colony’s eastern borderlands and western Xhosaland (emaXhoseni) have received considerable attention from historians. For reasons mostly relating to the availability of source material, the later wars are better known than the earlier ones. Thus the War of Hintsa (1834–35), the War of the Axe (1846–47), the War of Mlanjeni (1850–53) and the War of Ngcayecibi (1877–78) have received far more coverage by contemporaries and subsequently by historians than the eighteenth-century conflicts.2 The first detailed examination of Scientia Militaria, South African the 1799–1803 conflict, commonly known as Journal of Military Studies, Vol the Third Frontier War or third Cape–Xhosa 42, Nr 2, 2014, pp. -

Amathole District Municipality

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 2012 - 2017 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN Amathole District Municipality IDP 2012-2017 – Version 1 of 5 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT The Executive Mayor’s Foreword 4 Municipal Manager’s Message 5 The Executive Summary 7 Report Outline 16 Chapter 1: The Vision 17 Vision, Mission and Core Values 17 List of Amathole District Priorities 18 Chapter 2: Demographic Profile of the District 31 A. Introduction 31 B. Demographic Profile 32 C. Economic Overview 38 D. Analysis of Trends in various sectors 40 Chapter 3: Status Quo Assessment 42 1 Local Economic Development 42 1.1 Economic Research 42 1.2 Enterprise Development 44 1.3 Cooperative Development 46 1.4 Tourism Development and Promotion 48 1.5 Film Industry 51 1.6 Agriculture Development 52 1.7 Heritage Development 54 1.8 Environmental Management 56 1.9 Expanded Public Works Program 64 2 Service Delivery and Infrastructure Investment 65 2.1 Water Services (Water & Sanitation) 65 2.2 Solid Waste 78 2.3 Transport 81 2.4 Electricity 2.5 Building Services Planning 89 2.6 Health and Protection Services 90 2.7 Land Reform, Spatial Planning and Human Settlements 99 3 Municipal Transformation and Institutional Development 112 3.1 Organizational and Establishment Plan 112 3.2 Personnel Administration 124 3.3 Labour Relations 124 3.4 Fleet Management 127 3.5 Employment Equity Plan 129 3.6 Human Resource Development 132 3.7 Information Communication Technology 134 4 Municipal Financial Viability and Management 136 4.1 Financial Management 136 4.2 Budgeting 137 4.3 Expenditure -

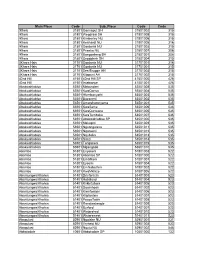

Mainplace Codelist.Xls

Main Place Code Sub_Place Code Code !Kheis 31801 Gannaput SH 31801002 315 !Kheis 31801 Wegdraai SH 31801008 315 !Kheis 31801 Kimberley NU 31801006 315 !Kheis 31801 Kenhardt NU 31801005 316 !Kheis 31801 Gordonia NU 31801003 315 !Kheis 31801 Prieska NU 31801007 306 !Kheis 31801 Boegoeberg SH 31801001 306 !Kheis 31801 Grootdrink SH 31801004 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 316 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Ses-Brugge AH 31701003 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Klippunt AH 31701002 315 42nd Hill 41501 42nd Hill SP 41501000 426 42nd Hill 41501 Intabazwe 41501001 426 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mabundeni 53501008 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQonsa 53501004 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Hlambanyathi 53501003 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Bazaneni 53501002 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Amatshamnyama 53501001 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaSeme 53501006 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQunwane 53501005 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaTembeka 53501007 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Abakwahlabisa SP 53501000 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Makopini 53501009 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Ngxongwana 53501011 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqotweni 53501012 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqubeka 53501013 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Sitezi 53501014 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Tanganeni 53501015 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mgangado 53501010 535 Abambo 51801 Enyokeni 51801003 522 Abambo 51801 Abambo SP 51801000 522 Abambo 51801 Emafikeni 51801001 522 Abambo 51801 Eyosini 51801004 522 Abambo 51801 Emhlabathini 51801002 522 Abambo 51801 KwaMkhize 51801005 522 Abantungwa/Kholwa 51401 Driefontein 51401003 523 -

Amathole District Municipality WETLAND REPORT | 2017

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY WETLAND REPORT | 2017 LOCAL ACTION FOR BIODIVERSITY (LAB): WETLANDS SOUTH AFRICA Biodiversity for Life South African National Biodiversity Institute Full Program Title: Local Action for Biodiversity: Wetland Management in a Changing Climate Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Southern Africa Cooperative Agreement Number: AID-674-A-14-00014 Contractor: ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – Africa Secretariat Date of Publication: June 2017 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FOREWORD Amathole District Municipality is situated within the Amathole District Municipality is also prone to climate central part of the Eastern Cape Province, which lies change and disaster risk such as wild fires, drought in the southeast of South Africa and borders the and floods. Wetland systems however can be viewed Indian Ocean. Amathole District Municipality has as risk reduction ecological infrastructure. Wetlands a land area of 21 595 km² with approximately 200 also form part of the Amathole Mountain Biosphere km of coastline stretching along the Sunshine Coast Reserve, which is viewed as a conservation and from the Fish River to just south of Hole in the Wall sustainable development flagship initiative. along the Wild Coast. Amathole District Municipality coastline spans two bio-geographical regions, namely Amathole District Municipality Integrated the warm temperate south coast and the sub-tropical Development Plan (IDP) recognises the importance east coast. of wetlands within the critical biodiversity areas of the Spatial Development Framework (SDF). Amathole District Municipality is generally in a good Sustainable development principles are an natural state; 83.3% of land comprises of natural integral part of Amathole District Municipality’s areas, whilst only 16.7% are areas where no natural developmental approach as they are captured in the habitat remains. -

Literatura, Lei De Terras E Colonialismo Em Sword and Assegai (África Do Sul, Década De 1890)

DOI: 10.47694/issn.2674-7758.v3.i8.2021.3050 ANNA HOWARTH E AS GUERRAS DAS FRONTEIRAS: LITERATURA, LEI DE TERRAS E COLONIALISMO EM SWORD AND ASSEGAI (ÁFRICA DO SUL, DÉCADA DE 1890) Evander Ruthieri da Silva1 Resumo: O período entre as décadas de 1870 e 1890 marcou um contexto de transformações sociais e políticas nos territórios localizados ao sul da África, ocasionadas pela expansão econômica e territorial decorrente das atividades na mineração e agricultura. Diversas medidas foram adotadas pelo colonato branco com o objetivo de controlar as terras ancestrais e a mão de obra da população negra, em especial, a legislação de terras. Diante desse quadro, o artigo concentra-se em Sword and Assegai (1899), de Anna Howarth, um romance de aventura ambientado nas “guerras das fronteiras” da região oriental da Colônia do Cabo (atualmente África do Sul) entre as décadas de 1830 a 1850. O destaque recai na caracterização dos guerreiros Xhosa, compreendendo a ênfase da romancista no “barbarismo” como uma forma de legitimação pública das práticas políticas coloniais, em especial, da apropriação de terras africanas empreendida pela elite colonial. Palavras-chave: História e Literatura. África do Sul. Colonialismo. ANNA HOWARTH AND THE FRONTIER WARS: LITERATUR, LAND LEGISLATION AND COLONIALISM IN SWORD AND ASSEGAI (SOUTH AFRICA, 1890s) Abstract: The period between the 1870s and 1890s marked a context of social and political changes in southern Africa, caused by economic and territorial expansion resulting from mining and agriculture activities. Several measures were adopted by white colonizers in order to control 30 African ancestral lands and workforce, such as by land legislation. -

National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act: Amendment Of

STAATSKOERANT, 27 MAART 2013 No. 36295 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS No. 236 27 March 2013 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT: PROTECTED AREAS ACT, 2003 (ACT NO. 57 OF 2003) AMENDMENT OF SCHEDULE 2 TO THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT: PROTECTED AREAS ACT, 2003 (ACT NO. 57 OF 2003) I, Bomo Edith Edna Molewa, Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs, in terms of section 20(6)(b) of the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, 2003 (Act No. 57 of 2003), hereby amend Schedule 2 to the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, 2003 (Act No. 57 of 2003) in the Schedule hereto. BOM ED IA MOLEWA MINISTER OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS 4 No. 36295 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 27 MARCH 2013 SCHEDULE In terms of section 20(6)(a) of the Act, each area defined shall be a national park under the name assigned to it in the Schedule. In terms of section 47(1) of the Act, the air space to a level of 2 500 feet above the highest point of the park (included in the Schedule) is included in the national park. [Schedule 2 amended by Proc. 294/78, s. 2 of Act 60/79, Proc. 201/79, Proc. 44/82, Proc.125/83, Proc. 132/83, Proc. 8/84, Proc. 210/84, Proc. 35/85, Proc. 138/85, GN 1933/86, GN 1934/86, GN 5/87, GN 1385/87, GN 1753/87, GN 2509/87, GN 2814/87, GN 2856/87, GN 225/88, GN 1047/88, GN 1249/88, GN 1490/88, GN 577/89, GN 703/89, GN 1374/89, GN 395/91, GN 1211/91, GN 2159/92, GN 214/93, GN 1766/93, GN 2201/93, GN 2202/93, GN 37/94, GN 183/94, GN 248/94, GN 857/94, GN 1227/94, GN 1228/94, GN 1705/94, GN 1947/94 , GN 2244/94, GN 1582/95, GN 1732/95, GN 537/96, GN 538/96, GN R599/96, GN 1077/96, GN 1138/96, GN 1139/96, GN 1140/96, s. -

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study For

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa Using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data Pilot Study – Catchment Management Area 15 by D van Bladeren, P K Zawada and D Mahlangu SRK Consulting & Council for Geoscience Report to the Water Research Commission on the project “Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data” WRC Report No 1260/1/07 ISBN 078-1-77005-537-7 March 2007 DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION During the past 10 years South Africa has experienced several devastating flood events that highlighted the need for more accurate and reasonable flood estimation. The most notable events were those of 1995/96 in KwaZulu-Natal and north eastern areas, the November 1996 floods in the Southern Cape Region, the floods of February to March 2000 in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Eastern Cape provinces and the recent floods in March 2003 in Montagu in the Western Cape. These events emphasized the need for a standard approach to estimate flood probabilities before developments are initiated or existing developments evaluated for flood hazards. The flood peak magnitudes and probabilities of occurrence or return period required for flood lines are often overlooked, ignored or dealt with in a casual way with devastating effects. The National Disaster and new Water Act and the rapid rate at which developments are being planned will require the near mass production of flood peak probabilities across the country that should be consistent, realistic and reliable.