Deprescribing for Older Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Or Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers and the Risk of Developing Rheumatoid Arthritis in Antihypertensive Drug Users

Jong, H.J.I. de, Vandebriel, R.J., Saldi, S.R.F., Dijk, L. van, Loveren, H. van, Cohen Tervaert, J.W., Klungel, O.H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis in antihypertensive drug users. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety: 2012, 21(8), 835-843 Postprint Version 1.0 Journal website http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pds.3291 Pubmed link http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22674737 DOI 10.1002/pds.3291 This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis in antihypertensive drug users†‡ HILDA J. I. DE JONG1,2,3, ROB J. VANDEBRIEL1, SITI R. F. SALDI3, LISET VAN DIJK4, HENK VAN LOVEREN1,2, JAN WILLEM COHEN TERVAERT5, OLAF H. KLUNGEL3,* ABSTRACT Purpose: Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are effective in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Next to effects on hypertension and cardiac function, these drugs have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties which may either facilitate or protect against the development of autoimmunity, potentially resulting in autoimmune diseases. Therefore, we determined in the current study the association between ACE inhibitor and ARB use and incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Methods: A matched case–control study was conducted among patients treated with antihypertensive drugs using the Netherlands Information Network of General Practice (LINH) database in 2001–2006. Cases were patients with a first-time diagnosis of RA. Each case was matched to five controls for age, sex, and index date, which was selected 1 year before the first diagnosis of RA. -

Ace Inhibitors (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme)

Medication Instructions Ace Inhibitors (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme) Generic Brand Benazepril Lotensin Captopril Capoten Enalapril Vasotec Fosinopril Monopril Lisinopril Prinivil, Zestril Do not Moexipril Univasc Quinapril Accupril stop taking Ramipril Altace this medicine Trandolapril Mavik About this Medicine unless told ACE inhibitors are used to treat both high blood pressure (hypertension) and heart failure (HF). They block an enzyme that causes blood vessels to constrict. This to do so allows the blood vessels to relax and dilate. Untreated, high blood pressure can damage to your heart, kidneys and may lead to stroke or heart failure. In HF, using by your an ACE inhibitor can: • Protect your heart from further injury doctor. • Improve your health • Reduce your symptoms • Can prevent heart failure. Generic forms of ACE Inhibitors (benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, and lisinopril) may be purchased at a lower price. There are no “generics” for Accupril, Altace Mavik, and of Univasc. Thus their prices are higher. Ask your doctor if one of the generic ACE Inhibitors would work for you. How to Take Use this drug as directed by your doctor. It is best to take these drugs, especially captopril, on an empty stomach one hour before or two hours after meals (unless otherwise instructed by your doctor). Side Effects Along with needed effects, a drug may cause some unwanted effects. Many people will not have any side effects. Most of these side effects are mild and short-lived. Check with your doctor if any of the following side effects occur: • Fever and chills • Hoarseness • Swelling of face, mouth, hands or feet or any trouble in swallowing or breathing • Dizziness or lightheadedness (often a problem with the first dose) Report these side effects if they persist: • Cough – dry or continuing • Loss of taste, diarrhea, nausea, headache or unusual fatigue • Fast or irregular heartbeat, dizziness, lightheadedness • Skin rash Special Guidelines • Sodium in the diet may cause you to retain fluid and increase your blood pressure. -

Icatibant Compared to Steroids and Antihistamines for ACE-Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema

KNOWLEDGE TO PRACTICE DES CONNAISSANCES ÀLA PRATIQUE CJEM Journal Club Icatibant Compared to Steroids and Antihistamines for ACE-Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema Reviewed by: Tudor Botnaru, MD, CM*; Antony Robert, MD, MASc*; Salvatore Mottillo, MD, MSc* syndromes, and acute heart failure NYHA class III or Article chosen IV,aswellasthosepregnantandlactating,were Bas M, Greve J, Stelter K, et al. A Randomized Trial of excluded. Icatibant in ACE-Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema. N Engl J Med 2015;372:418-25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312524. STUDY DESIGN This was an industry and government funded, multi-centre, Keywords: angioedema, icatibant, corticosteroids, ACE-inhibitor, antihistamines double-blind, double-dummy randomized phase 2 study. Block randomization was performed online. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio. Primary investigators and BACKGROUND patients were blinded to the treatment. Investigators who were responsible for the randomization, study-drug administration, and assessment of injection site reactions Angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibitor (ACEI) induced were aware of study assignments. Patients in the treatment angioedema occurs in 0.68% of those taking the group received icatibant 30 mg subcutaneously and those in medication1 and accounts for one-third of angioedema the control group (standard therapy group) received pre- cases treated in the emergency department. Upper airway dnisolone 500 mg and clemastine 2 mg (an antihistamine) compromise, potentially leading to acute laryngeal intravenously. Patients assessed the intensity of symptoms obstruction and death, may occur in up to 10% of cases.1,2 at several intervals within 48 hours. Blinded investigators Standard therapy consists of glucocorticoids and anti- further assessed the signs and symptoms. If there was no histamines. -

Angiotensin Modulators/Calcium Channel Blocker Combinations Review 02/05/2009

Angiotensin Modulators/Calcium Channel Blocker Combinations Review 02/05/2009 Copyright © 2004 - 2009 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Comments and suggestions may be sent to [email protected]. -

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors Summary Blood pressure reduction is similar for the ACE inhibitors class, with no clinically meaningful differences between agents. Side effects are infrequent with ACE inhibitors, and are usually mild in severity; the most commonly occurring include cough and hypotension. Captopril and lisinopril do not require hepatic conversion to active metabolites and may be preferred in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Captopril differs from other oral ACE inhibitors in its rapid onset and shorter duration of action, which requires it to be given 2-3 times per day; enalaprilat, an injectable ACE inhibitor also has a rapid onset and shorter duration of action. Pharmacology Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II through competitive inhibition of the angiotensin converting enzyme. Angiotensin is formed via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), an enzymatic cascade that leads to the proteolytic cleavage of angiotensin I by ACEs to angiotensin II. RAAS impacts cardiovascular, renal and adrenal functions via the regulation of systemic blood pressure and electrolyte and fluid balance. Reduction in plasma levels of angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor and negative feedback mediator for renin activity, by ACE inhibitors leads to increased plasma renin activity and decreased blood pressure, vasopressin secretion, sympathetic activation and cell growth. Decreases in plasma angiotensin II levels also results in a reduction in aldosterone secretion, with a subsequent decrease in sodium and water retention.[51035][51036][50907][51037][24005] ACE is found in both the plasma and tissue, but the concentration appears to be greater in tissue (primarily vascular endothelial cells, but also present in other organs including the heart). -

Effects of Statins on Renin–Angiotensin System

Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease Review Effects of Statins on Renin–Angiotensin System Nasim Kiaie 1,†, Armita Mahdavi Gorabi 1,†, Željko Reiner 2, Tannaz Jamialahmadi 3,4, Massimiliano Ruscica 5 and Amirhossein Sahebkar 6,7,8,9,* 1 Research Center for Advanced Technologies in Cardiovascular Medicine, Tehran Heart Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1411713138, Iran; [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (A.M.G.) 2 Department of Internal Diseases, School of Medicine, University Hospital Center Zagreb, Zagreb University, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] 3 Quchan Branch, Department of Food Science and Technology, Islamic Azad University, Quchan 9479176135, Iran; [email protected] 4 Department of Nutrition, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad 9177948564, Iran 5 Department of Pharmacological and Biomolecular Sciences, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 6 Biotechnology Research Center, Pharmaceutical Technology Institute, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad 9177948564, Iran 7 Applied Biomedical Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad 9177948564, Iran 8 School of Medicine, The University of Western Australia, Perth 6009, Australia 9 School of Pharmacy, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad 9177948564, Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] † Equally contributed. Abstract: Statins, a class of drugs for lowering serum LDL-cholesterol, have attracted attention because of their wide range of pleiotropic effects. An important but often neglected effect of statins is their role in the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) pathway. This pathway plays an integral role in the progression of several diseases including hypertension, heart failure, and renal disease. -

Online Appendix

The More We Die, The More We Sell? A Simple Test of the Home-Market Effect Online Appendix Arnaud Costinot Dave Donaldson MIT, CEPR, and NBER MIT, CEPR, and NBER Margaret Kyle Heidi Williams Mines ParisTech and CEPR MIT and NBER December 28, 2018 1 Contents A Theoretical Appendix3 A.1 Multinational Enterprises (Section III.1)..........................3 A.2 Log-Linearization (Section III.2)...............................3 A.3 Beyond Perfect Competition (Section III.3).........................6 A.3.1 Monopolistic Competition..............................6 A.3.2 Variable Markups...................................7 A.3.3 Endogenous Innovation...............................8 A.3.4 Price Regulations...................................9 A.4 Bilateral Sales (Section VI.1)................................. 12 B Empirical Appendix 12 B.1 Rich versus Poor Countries................................. 12 B.2 Additional Empirical Results................................ 13 B.3 Benchmarking IMS MIDAS data.............................. 13 B.3.1 Benchmarking to the OECD HealthStat Data................... 13 B.3.2 Benchmarking to the MEPS Data.......................... 14 B.4 ATC to GBD Mapping.................................... 15 2 A Theoretical Appendix A.1 Multinational Enterprises (Section III.1) In this appendix, we illustrate how to incorporate multinational production into our basic envi- ronment. Following Ramondo and Rodríguez-Clare(2013), suppose that each firm headquartered in country i that sells drugs targeting disease n in country j 6= i can choose the country l in which its production takes place. If l = i, then the firm exports, if l = j, it engages in horizontal FDI, and if l 6= i, j, it engages in platform FDI. Like in Ramondo and Rodríguez-Clare(2013), we assume that firm-level production functions exhibit constant returns to scale, but we further allow for external economies of scale at the level of the headquarter country for each disease. -

Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Fingerprint in Patients with Primary

1 181 P Wolf and others RAAS activity in adrenal 181:1 39–44 Clinical Study insufficiency Identifying a disease-specific renin– angiotensin–aldosterone system fingerprint in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency Peter Wolf1, Johanna Mayr1, Hannes Beiglböck1, Paul Fellinger1, Yvonne Winhofer1, Marko Poglitsch2, Alois Gessl1, Alexandra Kautzky-Willer1, Anton Luger1 and Correspondence should be addressed Michael Krebs1 to M Krebs 1Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine III, Medical University of Vienna and Email 2Attoquant Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria michael.krebs@meduniwien. ac.at Abstract Background: In patients suffering from primary adrenal insufficiency (AI) mortality is increased despite adequate glucocorticoid (GC) and mineralocorticoid (MC) replacement therapy, mainly due to an increased cardiovascular risk. Since activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) plays an important role in the modulation of cardiovascular risk factors, we performed in-depth characterization of the RAAS activity. Methods: Eight patients with primary AI (female = 5; age: 56 ± 21 years; BMI: 22.8 ± 2 kg/m2; mean blood pressure: 140/83 mmHg; hydrocortisone dose: 21.9 ± 5 mg/day; fludrocortisone dose: 0.061 ± 0.03 mg/day) and eight matched healthy volunteers (female = 5; age: 52 ± 21 years; BMI: 25.2 ± 4 kg/m2; mean blood pressure:135/84 mmHg) were included in a cross-sectional case–control study. Angiotensin metabolite profiles (RAS-fingerprints) were performed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Results: In patients suffering from primary AI, RAAS activity was highly increased with elevated concentrations of renin concentration (P = 0.027), angiotensin (Ang) I (P = 0.022), Ang II (P = 0.032), Ang 1-7 and Ang 1-5. -

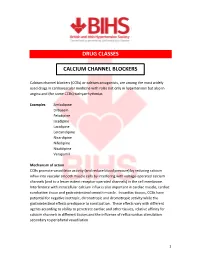

Calcium Channel Blockers (Ccbs)

DRUG CLASSES CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKERS Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) or calcium antagonists, are among the most widely used drugs in cardiovascular medicine with roles not only in hypertension but also in angina and (for some CCBs) tachyarrhythmias. Examples Amlodipine Diltiazem Felodipine Isradipine Lacidipine Lercanidipine Nicardipine Nifedipine Nisoldipine Verapamil Mechanism of action CCBs promote vasodilator activity (and reduce blood pressure) by reducing calcium influx into vascular smooth muscle cells by interfering with voltage-operated calcium channels (and to a lesser extent receptor-operated channels) in the cell membrane. Interference with intracellular calcium influx is also important in cardiac muscle, cardiac conduction tissue and gastrointestinal smooth muscle. In cardiac tissues, CCBs have potential for negative inotropic, chronotropic and dromotropic activity while the gastrointestinal effects predispose to constipation. These effects vary with different agents according to ability to penetrate cardiac and other tissues, relative affinity for calcium channels in different tissues and the influence of reflux cardiac stimulation secondary to peripheral vasodilation. 1 Although often considered as a single class, CCBs can be subdivided according to structural and functional distinctions. Dihydropyridine derivates : amlodipine, felodipine, isradipine, lacidipine, lercanidipine, nicardipine, nifedipine, nisoldipine Phenylalkylamine : verapamil Benzothiazepine derivative : diltiazem Dihydropyridine derivatives have pronounced -

Use of an Ace-Inhibitor to Treat Or Prevent Depression

Europaisches Patentamt J European Patent Office © Publication number: 0 413 929 A2 Office europeen des brevets EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number: 90111991.7 © lnt.Cl.S:A61K 31/675, A61K 31/10 © Date of filing: 25,06.90 The title of the invention has been amended © Applicant: E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, INC. (Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, A-lll, Lawrenceville-Princeton Road, P.O. Box 4000 7.3). Princeton New Jersey 08543-4000(US) © Priority: 26.06.89 US 371161 © Inventor: Sudilovsky, Abraham 712 Winchester Ave @ Date of publication of application: Lawrenceville, NJ 08648(US) 27.02.91 Bulletin 91/09 © Designated Contracting States: © Representative: Josif, Albert et al AT BE CH DE DK ES FR GB GR IT LI LU NL SE Baaderstrasse 3 D-8000 Munchen 5(DE) © Use of an ace-inhibitor to treat or prevent depression. © A method is provided for inhibiting onset of or treating depression by administering an ACE inhibitor, which is (S)-1-[6-amino-2-[[hydroxy(4-phenylbutyl)phosphenyl]oxy]-1-oxohexyl]-L-proline, fosinopril or zofenoprii, alone or in combination with an antidepressant drug such as lithium, over a prolonged period of treatment. CM O) CO o a. LU Xerox Copy Centre EP 0 413 929 A2 METHOD FOR PREVENTING OR TREATING DEPRESSION EMPLOYING AN ACE INHIBITOR The present invention relates to a method for preventing or treating depression by administering an ACE inhibitor, which is SQ 29,852, zofenopril, or fosinopril. The use of captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, for treating depression is disclosed in the following references: 5 Deicken, R.F., "Captopril Treatment of Depression," Biol Psychiatry, 1986; 21:1425-1428; Zubenko, G.S., "Mood-Elevating Effect of Captopril in Depressed Patients," Am. -

Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2020 EPHMRA ANATOMICAL

EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2020 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2020 "The Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products has been developed and maintained by the European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association (EphMRA) and is therefore the intellectual property of this Association. EphMRA's Classification Committee prepares the guidelines for this classification system and takes care for new entries, changes and improvements in consultation with the product's manufacturer. The contents of the Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products remain the copyright to EphMRA. Permission for use need not be sought and no fee is required. We would appreciate, however, the acknowledgement of EphMRA Copyright in publications etc. Users of this classification system should keep in mind that Pharmaceutical markets can be segmented according to numerous criteria." © EphMRA 2020 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2020 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 1 B BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS 28 C CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 35 D DERMATOLOGICALS 50 G GENITO-URINARY SYSTEM AND SEX HORMONES 57 H SYSTEMIC HORMONAL PREPARATIONS (EXCLUDING SEX HORMONES) 65 J GENERAL ANTI-INFECTIVES SYSTEMIC 69 K HOSPITAL SOLUTIONS 84 L ANTINEOPLASTIC AND IMMUNOMODULATING AGENTS 92 M MUSCULO-SKELETAL SYSTEM 102 N NERVOUS SYSTEM 107 P PARASITOLOGY 118 R RESPIRATORY SYSTEM 120 S SENSORY ORGANS 132 T DIAGNOSTIC AGENTS 139 V VARIOUS 141 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2020 INTRODUCTION The Anatomical Classification was initiated in 1971 by EphMRA. It has been developed jointly by Intellus/PBIRG and EphMRA. It is a subjective method of grouping certain pharmaceutical products and does not represent any particular market, as would be the case with any other classification system. -

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor–Induced Angioedema

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor–Induced Angioedema Abduljabar A. Theyab, MD; David S. Lee, MD; Amor Khachemoune, MD Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors the cumulative risk for developing angioedema is frequently are prescribed for the management of believed to be higher due to the long-term nature cardiovascular disorders. In addition to their ther- of treatment with ACE inhibitors and the fact that apeutic potential, ACE inhibitors are associated angioedema can occur at any point during therapy.6 with numerous adverse effects, some of which More than 3 decades after the first description of may be lethal. Angioedema is an uncommon but ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema, more is now serious acute event that may affect any individual understood about its underlying pathophysiology and taking an ACE inhibitor. This review outlines the variable clinical manifestations. In this article, we advances in our understanding of the pathogen- review the historical context of this phenomenon, esis, clinical presentation, and management of proposed molecular mechanisms, and clinical con- this medical emergency. siderations in the diagnosis and management of this Cutis. 2013;91:30-35. potentially fatal entity (Table). CUTISHistory ngiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibi- Angioedema was first described in the literature by tors are among the most commonly pre- Milton7 in 1876. The term angioneurotic angioedema scribed drugs in modern medicine with more was coined in 1882 by Quincke.8 Almost a century A 1 9 than 40 million patients using them. Numerous later, Wilkin et al characterized the association of ACE inhibitors are currently available (eg, captopril, angioedema with ACE inhibitor use in 1980 in a case benazepril, fosinopril, enalapril, zofenopril, ramipril, series involving 22 patients who received captopril, quinaprilDo hydrochloride, perindopril Not erbumine, lisino- which atCopy the time was a newly marketed antihyper- pril), differing primarily in their duration of action tensive agent.