West Mount Airy, Philadelphia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philadelphia House Price Indices

PHILADELPHIA HOUSE PRICE INDICES April 28, 2015 KEVIN C. GILLEN, Ph.D. [email protected] Disclaimers and Acknowledgments: The Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation at Drexel University provides this report free of charge to the public. The report is produced by Lindy Senior Research Fellow Kevin Gillen, in association with Meyers Research LLC. The author thanks Azavea.com, the Philadelphia Office of Property Assessment, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Case-Shiller MacroMarkets LLC, RealtyTrac, Zillow.com, Trulia.com and the NAHB for making their data publicly available. © 2015, Drexel University, All Rights Reserved. © 2015 Drexel University | [email protected] House Price Indices 1980-2015: 1980Q1=100 Philadelphia County v. Philadelphia MSA and U.S. Average 600.0 550.0 Phila. County* Phila. MSA** 500.0 U.S. Avg.** 450.0 400.0 350.0 300.0 250.0 200.0 150.0 Q1 100.0 * Empirically estimated by Kevin C. Gillen, Ph.D. **Courtesy of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). HPIs are available through 2014Q4 only. © 2015 Drexel University | [email protected] “MSA”=Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is the entire 9-county region. Total House Price Appreciation Rates by Geographic Market Philadelphia Philadelphia Period U.S.A.** County* MSA** 36-Year 137.8% 169.1% 127.6% 10-Year 4.5% 19.3% 8.4% 1-Year 4.1% 2.0% 4.8% 1-Quarter -0.3% -1.0% 1.3% *Empirically estimated by Kevin C. Gillen Ph.D. **Source: U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). These numbers are through 2014Q4 only. -

Roxborough Memorial Hospital School of Nursing

ROXBOROUGH MEMORIAL HOSPITAL SCHOOL OF NURSING INFORMATION FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS About Us ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 • The School of Nursing • The Hospital • The Neighborhood School of Nursing Accreditation/ Approval ......................................................................................................... 1 • Accreditation Commission For Education in Nursing, Inc. (ACEN) • The Pennsylvania State Board of Nursing Hospital Accreditation/ School of Nursing Membership. ..................................................................................... 2 • The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (TJC) • The Hospital & Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania (HAP) • The Delaware Valley Healthcare Council of Hospital Association of Pennsylvania (DVHC) The Academic Educational Program .................................................................................................................... 2 Admission Requirements ...................................................................................................................................... 3 • High School Requirements • College Requirements • Non-Discriminatory Policy • Admission Procedures • Time Committment Transfer Policy ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Curriculum -

Federally Qualified Health Centers in Philadelphia

Last updated: March 9th, 2020 by Jefferson Center for Urban Health Federally Qualified Health Centers in Philadelphia Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are clinics which provide free or low-cost medical care to residents of Philadelphia. These clinics will accept patients regardless of insurance status. Many clinics will accept walk-in patients, call ahead to request when walk in hours are. South Philadelphia Facility Address Zip Phone Services Philadelphia Health Center #2 1700 S Broad St Apt 201 19145 215-685-1810 Carl Moore Health Center (GPHA) 1401 S 31st St 19146 215-925-2400 Southeast Health Center (GPHA) 800 Washington Ave 19147 215-339-5100 Philadelphia Health Center #1 1930 S Broad St 19145 215-685-6570 STD/STI Testing Only Al-Assist Behavioral Care (GPHA) 1401 S 4th St 19147 215-339-1070 Snyder Avenue Dental Center (GPHA) 640 Snyder Ave 19148 215-334-4900 Reed Street Health Center 1325 S 33rd St Fl 3 19146 215-471-2761 .. West and Southwest Philadelphia Facility Address Zip Phone Services Philadelphia Health Center #3 555 S 43rd St 19104 215-685-7522 Philadelphia Health Center #4 4400 Haverford Ave 19104 215-685-7630 The Health Annex (FPCN) 6120 Woodland Ave 19142 215-727-4721 The Sayre Health Center 5800 Walnut St Ste 121 19139 215-474-4444 Woodland Ave Health Center (GPHA) 5000 Woodland Ave 19143 215-726-9807 Spectrum Community Health Center 5201 Haverford Ave 19139 215-471-2761 . Center City Philadelphia Facility Address Zip Phone Services Chinatown Medical Services (GPHA) 432 N 6th St 19123 215-925-2400 11th St -

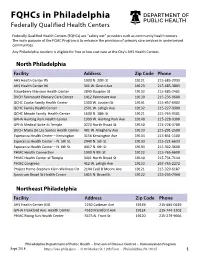

Fqhcs in Philadelphia Federally Qualified Health Centers

FQHCs in Philadelphia Federally Qualified Health Centers Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are “safety net” providers such as community health centers. The main purpose of the FQHC Program is to enhance the provision of primary care services in underserved communities. Any Philadelphia resident is eligible for free or low cost care at the City’s AHS Health Centers. North Philadelphia Facility Address Zip Code Phone AHS Health Center #5 1900 N. 20th St 19121 215-685-2933 AHS Health Center #6 301 W. Girard Ave 19123 215-685-3803 Strawberry Mansion Health Center 2840 Dauphin St 19132 215-685-2401 DVCH Fairmount Primary Care Center 1412 Fairmount Ave 19130 215-235-9600 QCHC Cooke Family Health Center 1300 W. Louden St 19141 215-457-6902 QCHC Family Health Center 2501 W. Lehigh Ave 19132 215-227-0300 QCHC Meade Family Health Center 1600 N. 18th St 19121 215-765-9501 GPHA Hunting Park Health Center 1999 W. Hunting Park Ave 19140 215-228-9300 GPHA Medical Suite At Temple 3223 North Broad St 19140 215-226-3789 DVCH Maria De Los Santos Health Center 401 W. Allegheny Ave 19133 215-291-2500 Esperanza Health Center – Kensington 3156 Kensington Ave 19134 215-831-1100 Esperanza Health Center – N. 5th St. 2940 N. 5th St 19133 215-221-6633 Esperanza Health Center – N. 6th St. 4417 N. 6th St 19134 215-302-3600 PHMC Health Connection 1900 N 9th St 19122 215-765-6690 PHMC Health Center at Temple 3401 North Broad St 19140 215-731-7144 PHMC Congreso 412 W. Lehigh Ave 19133 267-765-2272 Project Home-Stephen Klein Wellness Ctr 2144 Cecil B Moore Ave 19121 215-320-6187 Spectrum Broad St Health Center 1415 N. -

Housing Markets and Social Capital: the Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Culture Builds Community Culture Builds Community Evaluation—1997-2002 6-2001 Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation Mark J. Stern University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Stern, Mark J., "Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation" (2001). Culture Builds Community. 14. https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community/14 The release of the John Street administration’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI) in April 2001 marked a bold step by city government and the private sector to address the long-term problems of economic and social decline in the city of Philadelphia. The plan called for a differentiated strategy of public-private partnership with the goal of reinvigorating housing markets throughout the city. According to the NTI housing market analysis, more than four out of five Philadelphians lived in the bottom three market clusters—transitional, distressed, and reclamation. SIAP's Culture Builds Community inquiry was undertaken from 1996 to 2001 with support by the William Penn Foundation. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation Abstract This paper examines the housing markets described in the Philadelphia Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI), launched by Mayor John Street in April 2001, through the lens of social capital indicators. -

Community 2019

Southeastern Pennsylvania Community 2019 SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT Partnering Hospitals • Abington Hospital • Abington Lansdale Hospital • Chester County Hospital • Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Montgomery NEEDS ASSESSMENT HEALTH COMMUNITY • Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Elkins Park • Grand View Hospital • Holy Redeemer Hospital • Jefferson Bucks Hospital • Jefferson Frankford Hospital • Jefferson Torresdale Hospital • Thomas Jefferson University Hospital • Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience • Jefferson Methodist Hospital • Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania • Pennsylvania Hospital • Penn Presbyterian Medical Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................2 Philadelphia County, PA ..................................127 1. Center City .........................................................128 Partners ....................................................13 2. Far North Philadelphia ......................................130 1. Introduction .......................................................13 3. Far Northeast Philadelphia ...............................134 2. Participating Hospitals and Health Systems ....14 4. Lower Northeast Philadelphia ...........................138 a. Hospital Profiles 5. North Philadelphia – East .................................142 i. Overview of Hospital 6. North Philadelphia – West ................................146 ii. Past CHNA and Community 7. Northwest -

Philadelphia Neighborhoods Or a Recommendation of Particular Resources

A Guide to Philadelphia Neighborhood Resources for Infants, Toddlers, Preschoolers, & their Families City of Neighborhoods: A Guide to Philadelphia Neighborhood Resources for Infants, Toddlers, Preschoolers and Their Families (2007) Parents need to have a vision about where they see children participating and what they see them doing in the future. It is important for parents and professionals to have a vision of children participating in educational AND community-based opportunities. This guide focuses on assisting parents and professionals to envision a child in community-based opportunities. It is intended as a starting point to inspire thoughts about including children in community-based opportunities. Professionals can use it as a reference that can be carried with them as they visit children and families and work together with caregivers to identify general community resources that support the development and participation of all infants, toddlers and young children in everyday learning opportunities. A special thanks to the parents and professionals who contributed to the creation of the first edition (2002) of this guide and its 2007 revision: Mary Mikus, Suzanne Milbourne, Mary Muhlenhhaupt, Kimberly Rayfield and Jean Ann Vogelman. There are many comprehensive guides and directories that are available in Philadelphia to help professionals find a variety of resources for specific needs. This guide is not intended to replace the wide number of available resources. Nor, is it intended to be a comprehensive listing of all resources in all Philadelphia neighborhoods or a recommendation of particular resources. City of Neighborhoods: A Guide to Philadelphia Neighborhood Resources for Infants, Toddlers, Preschoolers & Their Families (2007) Envisioning children in the community ...........................................................................................................3 Examples of Community Resources............................................................................................................3 Where to begin . -

MSSP Internship Sites

ORGANIZATION MISSION ADDRESS WEBSITE Alliance for Excellent Education The Alliance for Excellent Education is a 1201 Connecticut Avenue http://www.all4ed.org/ policy, research and advocacy NW organization that is helping to Suite 901 formulate and implement a national Washington, DC 20036 policy to provide proven, research- based assistance to secondary schools that house the nation's most American Association of The American Association of University 1111 16th St. NW http://www.aauw.org/ University Women (AAUW) Women promotes equity in education Washington, DC 20036 for women and girls through advocacy, education, philanthropy and research. American Civil Liberties Union of The ACLU's Clara Bell Duvall P.O. Box 40008 http://www.aclupa.org/ Pennsylvania (ACLU) Reproductive Freedom Project's mission Philadelphia, PA 19106 is to ensure that individuals' reproductive rights are not compromised because of their race, youth or economic status. American Friends Service The American Friends Service 1501 Cherry Street http://afsc.org/ Committee (AFSC) Committee is a practical expression of Philadelphia, PA 19102 the faith of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). It is committed to the principles of nonviolence and justice. American Institutes for Research American Institutes for Research (AIR) 1000 Thomas Jefferson, NW www.air.org is a on profit research organization Washington, DC providing professional services in human service sectors domestically and overseas. American Youth Policy Forum American Youth Policy Forum's mission 1836 Jefferson Place NW http://www.aypf.org/ is to broaden the awareness and Washington, DC 20036 understanding of policymakers by strengthening the youth policymaking process and by bridging policy, practice and research. -

City of Philadelphia

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA Private Paving Fil DEPARTMENT OF STREETS MICHAEL CARROLL,P.E. 7th Floor – Municipal Services Building Commissioner 1401 John F. Kennedy Boulevard Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102-1676 ___________ ___, 2016 To: Developer You have elected to restore the utility ditches at the following addresses at your own cost rather than pay for the City to restore these ditches: Address Address Address Address Address Address You have the following responsibilities with regard to these ditches: • Inform your plumber that he must obtain a plumber fee waiver letter from the Streets Department prior to purchasing the plumber permit to open the street. These are available from the Highways Division, Room 930, Municipal Services Building, 1401 JFK Blvd. Call 215-686-5682 to arrange an appointment. • Maintain the ditches in a safe condition until final restoration. If the ditches are unsafe and must be made safe by the Streets Department, the developer or plumber will be billed for labor and material as determined by the Streets Department. • Restore the ditches in accordance with all applicable Streets rules and regulations regarding ditch restoration. • Schedule an appointment with the Highway district inspector to come to the site prior to the concrete pour on the day of the pour. The inspector will examine the backfill and observe the concrete pour to ensure that all Streets Department restoration standards are met. The Highway district office should be contacted at least two days in advance to schedule the site visit. Phone numbers -

Philadelphia's Housing Market Deteriorates Sharply in Q1

Philadelphia’s Housing Market Moves from Red Hot to White Hot in Q4 Prices, Sales and Turnover accelerate…and Philadelphia’s Price Appreciation Surpasses Most US Cities February 24, 2021: 2020 may have been unpleasant for people, but not for houses. Here’s the latest numbers: • The average price of Philadelphia homes rose by 5.0% in Q4 on a quality- and seasonally- adjusted basis. This is a significant acceleration from the previous quarter’s rate of 0.7%. • Philadelphia’s house prices are currently up an average of 12.8% from one year ago (YoY). This increase is nearly triple the city’s historic annual average house price appreciation rate of 4.5%, and it is also an acceleration of the YoY increase of 8.4% that Philadelphia experienced in the previous quarter. The last time that Philadelphia saw such large double-digit appreciation was in 2006. • After breaking the $200,000 barrier for the first time in Q2, the median house price in Philadelphia broke another record by hitting $210,000 in Q4. This was just the second time in 12 months that Philadelphia broke this record. • Philadelphia is also outpacing most other large US cities…and by a large margin Philadelphia’s house prices increased by an average of 12.8% in 2020, while Case-Shiller’s 10-City composite house price index (which excludes Philadelphia) is up by just 9.8% during the same period. • Annualized (YoY) house price changes in individual submarkets continue to be uniformly positive—and also well above their historic averages—but were also generally higher in the outer neighborhoods than in the central ones. -

Young Adult Resource Guide

RESOURCE GUIDE CHILD CARE & EARLY LEARNING • DOMESTIC VIOLENCE • DROP-IN CENTERS • DRUG & ALCOHOL TREATMENT • EDUCATION/ CAREER • FAMILY PLANNING/ REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH • FOOD RESOURCES • GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES • HOUSING/ SHELTER • LEGAL SERVICES • MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES • PARENTING EDUCATION • TEEN PARENT RESOURCES • OTHER RESOURCES Last updated January 15, 2021 This resource guide was compiled with the help of the Youth Justice Project Coalition The Youth Justice Project (YJP) was created in 2015 by Community Legal Services and Philadelphia Legal Assistance to more holistically address the needs of youth living in poverty in Philadelphia. YJP seeks to transform advocacy on behalf of low-income and vulnerable youth ages 16 to 24 by: 1) Creating a holistic and age-sensitive model for legal representation, 2) Developing strategic community partnerships to facilitate referrals and share resources among youth advocates in Philadelphia, and 3) Advancing needed policy changes to ensure youth can transition successfully to adulthood. Members of the Youth Justice Project Coalition include: Community Legal Services Philadelphia Legal Assistance Juvenile Law Center Education Law Center Youth Sentencing and Reentry Project Defender Association of Philadelphia The Pennsylvania DMC Youth/ Law Enforcement Corporation Legal Clinic for the Disabled ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHILD CARE/EARLY LEARNING....Page 1 La Puerta Abierta/The Open Door Child Care Information Services Mural Arts Crisis Care Nurseries Office of Vocational Rehabilitation Pennsylvania Early -

Communitysoutheastern Pennsylvania HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT TABLE of CONTENTS

CommunitySoutheastern Pennsylvania HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................2 Philadelphia County, PA ..........................................127 1. Center City .........................................................128 Partners ................................................................13 2. Far North Philadelphia ......................................130 1. Introduction .......................................................13 3. Far Northeast Philadelphia ...............................134 2. Participating Hospitals and Health Systems ....14 4. Lower Northeast Philadelphia ...........................138 a. Hospital Profiles 5. North Philadelphia – East .................................142 i. Overview of Hospital 6. North Philadelphia – West ................................146 ii. Past CHNA and Community 7. Northwest Philadelphia .....................................150 Benefit Impact Statements 8. River Wards .......................................................154 iii. Target Community Benefit 9. South Philadelphia – East .................................158 Service Areas and Demographics 10. South Philadelphia – West ................................162 3. Partner Organizations .......................................58 11. Southwest Philadelphia.....................................166 4. Our Collaborative Approach ..............................60 12. West Philadelphia ..............................................170 Bucks County, PA ....................................................69