Historic Preservation Recommendations for the Upper Northwest Planning District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1908 In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College M. Carey Thomas Bryn Mawr College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Thomas, M. Carey, In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College. (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Bryn Mawr College, 1908). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. #JI IN MEMORY OF WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Service held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. , • y • ./S-- I I .... ~ .. ,.,, \ \ " "./. "",,,, ~ / oj. \ .' ' \£,;i i f 1 l; 'i IN MEMORY OF \ WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Servic~ held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. • T his memorial address was published originally in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, Februar)I, I905, and is now reprinted by perntission of the Board of Editors of the Lantern, with slight verbal changesJ in response to the request of some of the many adm1~rers of the architectural beauty of Bryn 1\;[awr College, w'ho believe that it should be more widely l?nown than it is that the so-called American Collegiate Gothic was created for Bryn Mawr College by the genius of John Ste~vardson and ""Valter Cope. -

The Pennsylvania Assembly's Conflict with the Penns, 1754-1768

Liberty University “The Jaws of Proprietary Slavery”: The Pennsylvania Assembly’s Conflict With the Penns, 1754-1768 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the History Department in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Steven Deyerle Lynchburg, Virginia March, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Liberty or Security: Outbreak of Conflict Between the Assembly and Proprietors ......9 Chapter 2: Bribes, Repeals, and Riots: Steps Toward a Petition for Royal Government ..............33 Chapter 3: Securing Privilege: The Debates and Election of 1764 ...............................................63 Chapter 4: The Greater Threat: Proprietors or Parliament? ...........................................................90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................113 1 Introduction In late 1755, the vituperative Reverend William Smith reported to his proprietor Thomas Penn that there was “a most wicked Scheme on Foot to run things into Destruction and involve you in the ruins.” 1 The culprits were the members of the colony’s unicameral legislative body, the Pennsylvania Assembly (also called the House of Representatives). The representatives held a different opinion of the conflict, believing that the proprietors were the ones scheming, in order to “erect their desired Superstructure of despotic Power, and reduce to -

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania's Connection to Slavery

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania’s Connection to Slavery Clay Scott Graubard The University of Pennsylvania, Class of 2019 April 19, 2018 © 2018 CLAY SCOTT GRAUBARD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 OVERVIEW 3 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION 4 PRIMER ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 5 EBENEZER KINNERSLEY (1711 – 1778) 7 ROBERT SMITH (1722 – 1777) 9 THOMAS LEECH (1685 – 1762) 11 BENJAMIN LOXLEY (1720 – 1801) 13 JOHN COATS (FL. 1719) 13 OTHERS 13 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION CONCLUSION 15 FINANCIAL ASPECTS 17 WEST INDIES FUNDRAISING 18 SOUTH CAROLINA FUNDRAISING 25 TRUSTEES OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 31 WILLIAM ALLEN (1704 – 1780) AND JOSEPH TURNER (1701 – 1783): FOUNDERS AND TRUSTEES 31 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706 – 1790): FOUNDER, PRESIDENT, AND TRUSTEE 32 EDWARD SHIPPEN (1729 – 1806): TREASURER OF THE TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE 33 BENJAMIN CHEW SR. (1722 – 1810): TRUSTEE 34 WILLIAM SHIPPEN (1712 – 1801): FOUNDER AND TRUSTEE 35 JAMES TILGHMAN (1716 – 1793): TRUSTEE 35 NOTE REGARDING THE TRUSTEES 36 FINANCIAL ASPECTS CONCLUSION 37 CONCLUSION 39 THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 40 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 42 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 2 INTRODUCTION DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 3 Overview The goal of this paper is to present the facts regarding the University of Pennsylvania’s (then the College and Academy of Philadelphia) significant connections to slavery and the slave trade. The first section of the paper will cover the construction and operation of the College and Academy in the early years. As slavery was integral to the economy of British North America, to fully understand the University’s connection to slavery the second section will cover the financial aspects of the College and Academy, its Trustees, and its fundraising. -

Industries in Perth

Japan Chamber of Commerce & Industries in Perth INSIGHT Members Directory 2016 AON RISK SERVICED PTY LTD JCCIP ALLENS ASHURST AUSTRALIA CHIYODA OCEANIA PTY.LTD. INSIGHT JERA AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD.(CHUBU ELECTNIC AUSTRALIA) CLAYTON UTZ CORRS CHAMBERS WESTGARTH Directory 2016 CUBE SERVICE INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD. DELOITTE TOUCHE TOHMATSU DORAL PTY. LTD. EY HERBERT SMITH FREEHILLS H.I.S. AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. HITACHI AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. HYOGO PREFECTURAL GOVERNMENT CULTURAL CENTRE INPEX CORPORATION ITOCHU AUSTRALIA LTD. JAPAN ALUMINA ASSOCIATES (AUSTRALIA) PTY.LTD. JAPAN AUSTRALIA LNG (MIMI) PTY.LTD. JFE SHOJI TRADE AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. JGC CORPORATION JRCS AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. KANSAI ELECTRIC POWER AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. KING & WOOD MALLESONS KINTETSU WORLD EXPRESS (AUSTRALIA) PTY.LTD. KOMATSU AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. KPMG KYUSHU ELECTRIC AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. LAA INDUSTRIES PTY. LTD . MARUBENI AUSTRALIA LTD. MARUBENI IRON ORE AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. MARUBENI-ITOCHU TUBULARS OCEANIA PTY. LTD. MC RESOURCES AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. MITSUBISHI AUSTRALIA LIMITED MITSUBISHI MATERIALS TRADING CORPORATION MITSUI & CO. (AUSTRALIA) LTD. MITSUI E&P AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. MITUSI IRON ORE CORPORATION MITUSI IRON ORE DEVELOPMENT PTY.LTD. MITSUI O.S.K. BULK SHIPPING PTY LTD. MIZUHO BANK LTD. OSAKA GAS AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. PRICEWATERHOUSE COOPERS AUSTRALIA SHARK BAY SALT PTY. LTD. SOJITZ AUSTRALIA LIMITED PERTH OFFICE SUMITOMO AUSTRALIA PTY.LTD. SUMITOMO MITSUI BANKING CORPORATION PERTH BRANCH SUMMIT RURAL (WA) PTY.LTD. JERA DARWIN INVESTMENT PTY.LTD, (TEPCO AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD.) TOHO GAS AUSTRALIA -

INVEST in NEIGHBORHOODS: an Agenda for Livable Philadelphia Communities

INVEST IN NEIGHBORHOODS: An Agenda for Livable Philadelphia Communities Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations May 2003 PACDC Members CDC Members Bridesburg/Kensington CDC Production Kensington Area Revitalization Project, New Kensington CDC Over the past ten years, our CDC Center City members have leveraged over $650 Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation million in investment to our neigh- borhoods. They have: Chestnut Hill/Germantown East Falls Development Corporation, Greater Germantown Housing Development Corpora- Developed nearly 3,500 homes and tion, Mt. Airy USA, Nicetown CDC, Urban Resources Development Corporation apartments for first time home buyers, lower income families and special needs Lower North Philadelphia populations Advocate CDC, Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha, Inc., Friends Rehabilitation Pro- gram, Kensington South CDC, Project H.O.M.E., Renaissance CDC, Spring Garden Civic Asso- Created over 1.1 million square feet ciation, Women’s Community Revitalization Project, Yorktown CDC of commercial and facilities space, including supermarkets and retail space, job training centers, child care centers, Near Northeast Philadelphia and charter schools Frankford CDC, Frankford United Neighbors CDC, Mayfair CDC Assisted or created over 2,000 Olney/Oak Lane businesses Campus Boulevard Corporation, Fern Rock-Ogontz-Belfield CDC, Greater Olney Circle of Friends CDC, Inter-Community Development Corporation, Ogontz Avenue Revitalization Corporation, Provided job training or placement for -

HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 Student HADDBDDH 1948- 1949

P. M. C. 0 Student -HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 Student HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 0 Pennsylvania 5J1ilita'Ly College Cfteste\, Pennsylvania FRESHMAN HANDBOOK 3 PREFACE TO THE STUDENTS The Student Handbook is published for you and is supported by funds provided by the non-athletic activities fee. It was firs~ published in September 1948 as the Fresh man Handbook. This year it is available for all students in the hope that it will be a useful and profitable guide. Its purpose is to anticipate and answer questions you may have, to acquaint you with the history of P.M.C., to apprise you of academic rules and regulations, to point out what is ex pected of you by the faculty and yo~ fel low students, and to urge you to participate in some extra-curricular activity. THE EDITOR. 4 FRESHMAN HANDBOOK ••• • • • II I • I I- ~~-------· ----· FRESHMAN HANDBOOK 6 PRESIDENT HYATT'S MESSAGE TO T"HE MEMBERS OF THE ENTERING CLASS It is my great pleasure, in behalf of the faculty and the student body, to extend t9 you, the members of the new freshman class, both cadets and veteran students, a most cordial welcome to the Pennsylvania Military College. It is only since the last war that P.M.C. has had a civilian student body in addition to its corps of cadets. It has been gratify ing to see these two groups of college stu dents work hand in hand toward a common goal-a stronger and better P.M.C. I am sure that you, too, will cooperate in the same manner. -

List of Tax Reform Good News

List of Tax Reform Good News 1,200 examples of pay raises, charitable donations, special bonuses, 401(k) match hikes, business expansions, benefit increases, and utility rate reductions attributed to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act As of August 17, 2020. Please send any additions to this list to John Kartch at [email protected] This list and all 50 state lists are constantly updated – please access this national list and all 50 state lists at www.atr.org/list A 1A Auto, Inc. (Westford, Massachusetts) -- Bonuses for all full-time employees: Massachusetts based online auto parts retailer 1A Auto announced across the board cash bonuses for all full-time employees. CEO Rick Green says that the decision was based on recent changes to tax policy. In a company meeting Wednesday, Green told employees, "Ultimately the tax savings will be passed to our customers in the form of lower prices, but we want to also share some of the savings with you, our hard-working employees." Jan. 25, 2018 1A Auto, Inc. press release 2nd South Market (Twin Falls, Idaho) -- A food hall is opening because of the TCJA Opportunity Zone program, and is slated to create new jobs: One of the nation’s fastest-growing trends, food halls, is coming to Twin Falls. 2nd South Market, slated to open this summer, will be housed in the historic 1926 downtown Twin Falls building formerly occupied by the Salvation Army. 2ndSouth Market will be the first Opportunity Zone project to open in Idaho and the state’s third Opportunity Zone investment. -

Some of the Busiest, Most Congested and Stress-Inducing Traffic Is Found on Roads Crossing Southeastern Pennsylvania—The Penns

Protect and Preserve What You Can Do It’s easy to get involved in the Pennypack Greenway. The possibilities are limited only by your imagination. n Encourage your municipal officials to protect the Within one of the most rapidly developing environmentally sensitive lands identified in local parts of Pennsylvania is found a creek open space plans. n Get dirty! Participate in one of the creek cleanups and watershed system that has sustained held throughout the Greenway. remnants of the primal beauty and wildlife n Stand up for the creek at municipal meetings when your commissioners and council members are that have existed within it for thousands discussing stormwater management. of years. It is the Pennypack Creek n Enjoy one of the many annual events that take place along the Greenway such as sheep shearing, Maple watershed, a system that feeds Pennypack Sugar Day, and Applefest at Fox Chase Farm. Creek as it runs from its headwaters in Bucks and Montgomery counties, through If You Have a Yard n Make your yard friendlier for wildlife by planting Philadelphia and into the Delaware River. native trees, shrubs and wildflowers. Audubon Publicly accessible pockets of this graceful Pennsylvania’s “Audubon At Home” program can help. n Minimize or eliminate your use of pesticides, natural environment are used daily by herbicides, and fertilizers. thousands of citizens, young and old, providing a refuge from the pressures n Control (or eliminate) aggressive non-native plants of daily life. Yet this system faces real threats. Undeveloped land alongside infesting your garden. n Reduce the paving on your property to allow Pennypack Creek is sought after for development and there isn’t a protected rainwater to percolate into the soil, and install rain passage through it. -

The First Design for Fairmount Park

The First Design for Fairmount Park AIRMOUNT PARK IN PHILADELPHIA is one of the great urban parks of America, its importance in landscape history exceeded only by FNew York’s Central Park. Its name derives from the “Faire Mount” shown on William Penn’s plan of 1682, where the Philadelphia Museum of Art now perches, and where the gridded Quaker city suddenly gives way to an undulating scenery of river and park. Measuring over 3,900 acres, it is one of the world’s largest municipal parks. Nonetheless, for all its national importance, the origin of the park, its philosophical founda- tions, and its authorship have been misunderstood in the literature.1 About the principal dates there is no dispute: in 1812–15 a municipal waterworks was built on the banks of the Schuylkill, the site of which soon became a popular resort location and a subject of picturesque paintings; in 1843 the city began to acquire tracts of land along the river to safeguard the water supply; in 1859 the city held a competition for the design of a picturesque park; finally, in 1867, the Fairmount Park Commission was established to oversee a much larger park, whose layout was eventually entrusted to the German landscape architect Hermann J. Schwarzmann. This is the version rehearsed in all modern accounts of the park. All texts agree that 1867 marks the origin of the park, in conception and execution. They depict the pre–Civil War events as abortive and inconclusive; in particular, they dismiss the 1859 competition. According to George B. Tatum, writing in 1961, a series of “plans were prepared,” I am indebted to five generous colleagues who read this manuscript and contributed suggestions: Therese O’Malley of CASVA; Sheafe Satterthwaite and E. -

Certificate of Authority Change of Name Charter

11/05/2015 MONTGOMERY COUNTY LAW REPORTER Vol. 152, No. 45 Willow Step, Inc. has been incorporated under the provisions of the Pennsylvania Business Corporation Law CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORITY of 1988. Albert L. Chase, Esquire Notice is hereby given that a Foreign Registration 2031 N. Broad Street, Ste. 137 Statement has been filed with the Department Lansdale, PA 19446-1003 of State of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for the purpose of obtaining a Certificate of Authority pursuant to the provisions of CHARTER APPLICATION NONPROFIT the Business Corporation Law of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Act of December 21, 1988 (P.L. 1444, Ignite Ministry, Inc. has been incorporated No. 177). under the provisions of the PA Nonprofit Corporation The name of the corporation is: Diversus, Inc. Law of 1988. The State of incorporation is Delaware and Mullaney Law Offices the address of its principal office is 13010 Morris Road, 598 Main Street Building I, 6th Floor, Alpharetta, GA 30004. P.O. Box 24 The address of the corporation’s registered office Red Hill, PA 18076 in Pennsylvania is: 1012 W. 9th Avenue, Suite 250, King of Prussia, PA 19406. Scott H. Spencer, Esquire Notice is hereby given that Operation Inspiration Stevens & Lee, has been incorporated under the Pennsylvania Business 17 N. 2nd Street, 16th Floor Corporation Law of 1988 as a Domestic Nonprofit Harrisburg, PA 17101 Corporation, effective July 3, 2015. Kenneth E. Picardi, Esquire Yergey. Daylor. Allebach. Scheffey. Picardi. CHANGE OF NAME 1129 East High Street P.O. Box 776 IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF Pottstown, PA 19464-0776 MONTGOMERY COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA CIVIL ACTION - LAW NO. -

Transportation Plan

CHAPTER EIGHT Transportation Plan Broadly defined, the transportation plan is a plan for the movement of people and goods throughout the township. More specifically, it documents township roadway classifications and traffic volumes, while providing recommendations on mitigating congestion and safety problems. It also examines alternative transportation modes such as public transit and pedestrian and bicycle pathways. With the degree to which the recommendations contained in this chapter are implemented, it would not only allow for the continued efficient flow of people and goods, but will also help to maintain and enhance the quality of life currently enjoyed in the township. This chapter is comprised of three main sections: roadways, public transit, and pedestrian/bicycle path- ways. Each section contains its own specific set of recommendations. Roadways The township’s original comprehensive plan of 1965 presents a bold, optimistic outlook on the future of Whitemarsh’s road network. Traffic congestion would be eliminated through the construction of new roads and bridges; expressways are envisioned bisecting the township and a bridge would provide a direct connec- tion to the Schuylkill Expressway. Hazardous intersections would be eliminated through improvements and realignments. An ambitious document, it is a reflection of a time when the answer to current woes was new construction that was bigger and therefore better. While the merits of new expressways and wider roads are still a debatable point, for the township it is moot. Despite the fact that this plan contained many valid ideas, most of the new roadway opportunities have been lost through subsequent development and a greater appre- ciation for older structures makes road widenings difficult. -

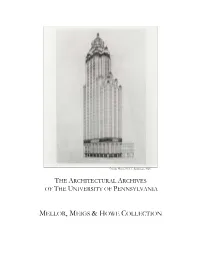

Finding Aid for the Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The

George Howe, P.S.F.S. Building, ca. 1926 THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MELLOR, MEIGS & HOWE COLLECTION (Collection 117) A Finding Aid for The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection, 1915-1975, bulk 1915-1939. Coll. ID: 117 Origin: Mellor, Meigs & Howe, Architects, and successor, predecessor and related firms. Extent: Architectural drawings: 1004 sheets; Photographs: 83 photoprints; Boxed files: 1/2 cubic foot. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection comprises architectural records related to the practices of Mellor, Meigs & Howe and its predecessor and successor firms. The bulk of the collection documents architectural projects of the following firms: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Mellor & Meigs; Howe and Lescaze; and George Howe, Architect. It also contains materials related to projects of the firms William Lescaze, Architect and Louis E. McAllister, Architect. The collection also contains a small amount of personal material related to Walter Mellor and George Howe. Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group.