Reflecting on Zimbabwe's Constitution-Making Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Courage Newsletter

Civil Courag e News Journal of the Civil Courage Prize Vol. 11, No. 2 • September 2015 For Steadfast Resistance to Evil at Great Personal Risk Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Guatemalans Claudia Paz y Paz and Yassmin Micklethwait to Deliver Keynote Barrios Win 2015 Civil Courage Prize Speech at the Ceremony for Their Pursuit of Justice and Human Rights ohn Micklethwait, Bloomberg’s his year’s recipients of the JEditor-in-Chief, oversees editorial TCivil Courage Prize, Dr. content across all platforms, including Claudia Paz y Paz and Judge Yassmin news, newsletters, Barrios, are extraordinary women magazines, opinion, who have taken great risks to stand television, radio and up to corruption and injustice in digital properties, as their native Guatemala. well as research ser- For over 18 years, Dr. Paz y Paz vices such as has been dedicated to improving her Claudia Paz y Paz Bloomberg Intelli - country’s human rights policies. She testing, wiretaps and other technol - gence. was the national consultant to the ogy, she achieved unprecedented re - Prior to joining UN mission in Guatemala and sults in sentences for homicide, rape, Bloomberg in February 2015, Mickle- served as a legal advisor to the violence against women, extortion thwait was Editor-in-Chief of The Econo - Human Rights Office of the Arch - and kidnapping. mist, where he led the publication into the bishop. In 1994, she founded the In - In a country where witnesses, digital age, while expanding readership stitute for Com- prosecutors, and and enhancing its reputation. parative Criminal judges were threat - He joined The Economist in 1987, as Studies of Guate- ened and killed, she a finance correspondent and served as mala, a human courageously Business Editor and United States Editor rights organization sought justice for before being named Editor-in-Chief in that promotes the victims of the 2006. -

Ccpnewsletter Aug07.Qxd (Page 1)

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” —Edmund Burke AUGUST 2007 Civil Courage VOL. 3, NO. 2 Steadfast Resistance to Evil at Great Personal Risk The Newsletter of The Train Foundation 67A East 77 Street,CCP New York, NY 10075 • Tel: 212.737.1011 • Fax: 212.737.6459 • www.civilcourageprize.org The Rev. Phillip Buck, formerly of North Korea, Wins 2007 Civil Courage Prize for Help to Fleeing Refugees Aided Thousands to Escape North Korea; Was Imprisoned by Chinese for 15 Months The Rev. Phillip Jun Buck, who was born in North Korea in 1941, has been selected as the winner of the 2007 Civil Courage Prize of The Train Foundation. He will be awarded the Prize of $50,000 at a ceremony to be held October 16 in New York. His life has been marked by tireless efforts to help refugees from North Korea to escape that country, many through China, which, contrary to international law,tracks down and repatriates refugees. Since Pyong Yang deems it a crime to leave the country,the refugees returned by China are treated as criminals, and are subject to imprisonment in a gulag or worse. China persecutes those who aid refugees, as well. Rev. Buck himself was arrested in Yanji, China in May 2005, while aiding refugees, and spent 15 months in prison there.Thanks to the U.S. Embassy,his case was kept before the Chinese authorities and he was released in August 2006, though he suffered from malnutrition, intense interrogation and sleep deprivation. -

HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS on the FRONT LINE Debut A5.Qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 2 Debut A5.Qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 3

debut_a5.qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 1 HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS ON THE FRONT LINE debut_a5.qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 2 debut_a5.qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 3 Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders / FIDH and OMCT Human Rights Defenders on the Front Line Annual Report 2004 Foreword by Lida Yusupova debut_a5.qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 4 Drafting, editing and co-ordination : Catherine François, Julia Littmann, Juliane Falloux and Antoine Bernard (FIDH) Delphine Reculeau, Mariana Duarte, Anne-Laurence Lacroix and Eric Sottas (OMCT) The Observatory thanks Marjane Satrapi, comic strip author and illustrator of the annual report cover, for her constant and precious support. The Observatory thanks all partner organisations of FIDH and OMCT, as well as the teams of these organisations. Distribution : this report is published in English, Spanish and French versions. The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) authorise the free reproduction of extracts of this text on condition that the source is credited and that a copy of the publication containing the text is sent to the respective International Secretariats. FIDH – International Federation for Human Rights 17, passage de la Main d'Or – 75 011 Paris – France Tel.: + 33 (0) 1 43 55 25 18 – Fax: + 33 (0) 1 43 55 18 80 [email protected] / www.fidh.org OMCT – World Organisation Against Torture 8, rue du Vieux-Billard – Case postale 21 – 1211 Geneva 8 – Switzerland Tel.: + 41 22 809 49 39 – Fax: + 41 22 809 49 29 [email protected] / www.omct.org debut_a5.qxp 04/04/2005 12:04 Page 5 FOREWORD UNITED AGAINST HORROR by Lida Yusupova Human rights defenders in Chechnya have to work in an extremely difficult environment. -

Annual Report Sometimes Brutally

“Human rights defenders have played an irreplaceable role in protecting victims and denouncing abuses. Their commitment Steadfast in Protest has exposed them to the hostility of dictatorships and the most repressive governments. […] This action, which is not only legitimate but essential, is too often hindered or repressed - Annual Report sometimes brutally. […] Much remains to be done, as shown in the 2006 Report [of the Observatory], which, unfortunately, continues to present grave violations aimed at criminalising Observatory for the Protection and imposing abusive restrictions on the activities of human 2006 of Human Rights Defenders rights defenders. […] I congratulate the Observatory and its two founding organisations for this remarkable work […]”. Mr. Kofi Annan Former Secretary General of the United Nations (1997 - 2006) The 2006 Annual Report of the Observatory for the Protection Steadfast in Protest of Human Rights Defenders (OMCT-FIDH) documents acts of Foreword by Kofi Annan repression faced by more than 1,300 defenders and obstacles to - FIDH OMCT freedom of association, in nearly 90 countries around the world. This new edition, which coincides with the tenth anniversary of the Observatory, pays tribute to these women and men who, every day, and often risking their lives, fi ght for law to triumph over arbitrariness. The Observatory is a programme of alert, protection and mobilisation, established by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) in 1997. It aims to establish -

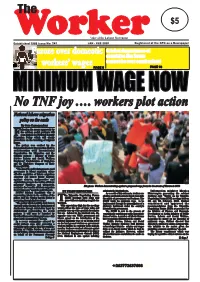

No TNF Joy .… Workers Plot Action

The $5 Voice of the Labour Movement Established 88 19 Is u e No: 2 41 JAN - FEB 2 20 0 Regist er e dt e at h G wPO as a Ne p s aper Cricket: importance of Furore over domestic countries Zim Tours workers’ wages cannot be over emphasised PAGE 6 PAGE 16 MINIMUM WAGE NOW No TNF joy .… workers plot action National labour migration policy on the cards By Own Correspondent ollowing the recent approvals by the cabinet, social partners will Fsoon launch the National Labour Migration Policy which will clarify procedures on the handling of migrant issues. The policy was crafted by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in collaboration with International Organisation for Migration and the tripartite partners - Ministry of Public Service Labour and Social Welfare; Employers' Confederation of Zimbabwe and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU). “The aim of the policy is to promote good governance in labour migration; ensure effective regulation of labour migration; empower and protect labour migrants against abuses, malpractice and exploitation; promote the welfare of labour migrants' families; and ultimately, File photo: Workers demonstrating against a proposed wage freeze in the streets of Harare in 2016 maximize the benefits of labour migration for development,” reads the policy in part. BY STAFF REPORTER salaries to the interbank rate. Information minister Monica ZCTU's Michael Kandukutu who is As a result of this stalemate, workers are Mutsvangwa presenting the cabinet representing labour in the crafting of the he Tripartite Negotiating Forum plotting a national action to knock sense into decisions said; “Update on the Tripartite policy, told The Worker that the policy is (TNF) meetings have come and the minds of government and business. -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Zimbabwe April 2004 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the Document 1.1 –1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 – 4.193 Independence 1980 4.1 - 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983-87 4.6 - 4.9 Elections 1995 & 1996 4.10 - 4.11 Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) 4.12 - 4.13 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.14 - 4.23 - Background 4.14 - 4.16 - Election Violence & Farm Occupations 4.17 - 4.18 - Election Results 4.19 - 4.23 - Post-election Violence 2000 4.24 - 4.26 - By election results in 2000 4.27 - 4.28 - Marondera West 4.27 - Bikita West 4.28 - Legal challenges to election results in 2000 4.29 Incidents in 2001 4.30 - 4.58 - Bulawayo local elections, September 2001 4.46 - 4.50 - By elections in 2001 4.51 - 4.55 - Bindura 4.51 - Makoni West 4.52 - Chikomba 4.53 - Legal Challenges to election results in 2001 4.54 - 4.56 Incidents in 2002 4.57 - 4.66 - Presidential Election, March 2002 4.67 - 4.79 - Rural elections September 2002 4.80 - 4.86 - By election results in 2002 4.87 - 4.91 Incidents in 2003 4.92 – 4.108 - Mass Action 18-19 March 2003 4.109 – 4.120 - ZCTU strike 23-25 April 4.121 – 4.125 - MDC Mass Action 2-6 June 4.126 – 4.157 - Mayoral and Urban Council elections 30-31 August 4.158 – 4.176 - By elections in 2003 4.177 - 4.183 Incidents in 2004 4.184 – 4.191 By elections in 2004 4.192 – 4.193 5 State Structures 5.1 – 5.98 The Constitution 5.1 - 5.5 Political System: 5.6 - 5.21 - ZANU-PF 5.7 - -

Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders / FIDH and OMCT

Debut.qxd 02/04/04 17:17 Page 1 HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS IN A «SECURITY FIRST» ENVIRONMENT Debut.qxd 02/04/04 17:17 Page 2 Debut.qxd 02/04/04 17:17 Page 3 Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders / FIDH and OMCT Human Rights Defenders in a «Security First» Environment Annual Report 2003 Foreword by Shirin Ebadi Nobel Peace Prize Debut.qxd 02/04/04 17:17 Page 4 Drafting, editing and co-ordination: Juliane Falloux, Catherine François and Antoine Bernard, with the collaboration of Julia Littman (FIDH). Anne-Laurence Lacroix, Alexandra Kossin, Sylvain de Pury and Eric Sottas (OMCT). The Observatory thanks Marjane Satrapi, author of comics, for her collaboration to this report, as well as all the partner organisations of FIDH and OMCT, as well as the teams of these organisations. Distribution: this report is published in English, Spanish and French versions. A German version is available on the Web sites of both organisations. The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) authorise the free reproduction of extracts of this text on condition that the source is credited and that a copy of the publication containing the text is sent to the respective International Secretariats. FIDH – International Federation for Human Rights 17, passage de la Main d'Or – 75 011 Paris – France Tel.: + 33 (0) 1 43 55 25 18 – Fax: + 33 (0) 1 43 55 18 80 [email protected]/www.fidh.org OMCT – World Organisation Against Torture 8, rue du Vieux-Billard – Case postale 21 – 1211 Geneva 8 – Switzerland Tel.: + 41 22 809 49 39 – Fax: + 41 22 809 49 29 [email protected]/www.omct.org Debut.qxd 02/04/04 17:17 Page 5 FOREWORD by Shirin Ebadi 2003 Nobel Peace Prize After the wave of arrests in the 1980s, which forced human rights defenders into exile or long prison sentences with loss of civic rights, it was particularly difficult to resume the fight for fundamental freedoms in Iran. -

TF Human Rights Committee’S 2005 Decision Requiring the Representatives

Civil Courage News Journal of the Civil Courage Prize Vol. 9, No. 2 • September 2013 For Steadfast Resistance to Evil at Great Personal Risk Physician Denis Mukwege Wins 2013 Civil Courage Prize for Championing Victims of Gender-based Violence in DR Congo New York Times Columnist Bill Keller to Deliver Keynote Speech ill Keller, Op-Ed columnist and Bformer executive editor of The New York Times, will give the keynote address at the Civil Courage Prize Ceremony this October 15th his year’s Civil Courage Prize needing surgery and aftercare. On the at the Harold Pratt House in New will be awarded to Denis subject of sexual violence as a weapon, York City. Mr. Keller was at the helm TMukwege. Founder of the Dr. Mukwege has noted that “It’s a of The New York Times for eight Panzi Hospital in Bukavu in Eastern strategy that destroys not only the vic- years, during which time the paper Congo, Dr. Mukwege is renowned for tim; it destroys the whole family, the won 18 Pulitzer Prizes and expanded his treatment of survivors of sexual vio- whole community.” its Internet presence and digital sub- lence and his active public denunciation In September 2012, Dr. Mukwege scription. Previous to that he had of mass rape. The Panzi Hospital has spoke publicly, at the UN in New York, been both managing editor and for- treated more than 30,000 women since of the need to prosecute the crime of eign editor for a number of years, its inception in 1999, many of whom mass rape and rape as a tool of war and and had been chief of the Johannes- have suffered the intolerable conse- terror. -

January 2020

Civil Courage News Journal of the Civil Courage Prize Vol. 16, No. 1 • January 2020 For Steadfast Resistance to Evil at Great Personal Risk Videos at the Ceremony The 2019 Civil Courage Prize- Highlight the Importance Winner Gonzalo Himiob Santomé of the Laureate's Wo r k Speaks of Venezuela's Struggles t this year's Civil Courage Prize n October 21, 2019, the normal citizen," who is willing to A ceremony, highlights included O Train Foundation award- fight "in order to get peace, justice, videos about the human rights work ed the Civil Courage Prize to and freedom back when it has been done by Gonzalo Himiob Santomé and Venezuelan lawyer, writer, musician, wrongfully taken away." The Prize Foro Penal in Venezuela. poet, and human rights activist "reminds us that anyone who truly Because she was not able to attend, Gonzalo Himiob wishes to…can former U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Santomé. He, and make a difference." Samantha Power, who nominated Alfredo Romero, He noted how Himiob for the prize, sent a video. with whom he "the evil, violence, At the U.N., Power became familiar "shares the honor," persecution, and with Himiob's work; both his personal co-founded Foro death, has invaded involvement in individual cases and his Penal, an organiza- almost each aspect coordination of the efforts of Foro tion that helps to of our lives," mak- Penal’s lawyers and volunteers who help free prisoners arbi- ing people believe people "subjected to politically moti- trarily detained by "the lines between vated arrests." She also saw their work his government, what is correct and with families of those killed by security and also documents Gonzalo Himiob Santomé incorrect, what is forces while they protested the corrup- detainees, political prisoners, right and wrong, are vague and even tion and failure of the Maduro regime. -

Zimbabwe: the Road to Reform Or Another Dead End?

ZIMBABWE: THE ROAD TO REFORM OR ANOTHER DEAD END? Africa Report N°173 – 27 April 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. DEVELOPMENTS UNDER THE INCLUSIVE GOVERNMENT ............................. 2 A. GPA REFORM PROGRESS ............................................................................................................. 3 B. OUTSTANDING ISSUES .................................................................................................................. 6 C. RE-RUN OF THE 2008 ELECTION VIOLENCE? ................................................................................ 8 III. CONSTITUTION-MAKING ......................................................................................... 11 A. GPA PROVISIONS AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ........................................................... 11 B. FUNDING .................................................................................................................................... 12 C. ALL-STAKEHOLDERS CONFERENCE ............................................................................................ 12 D. KEY ISSUES ................................................................................................................................ 13 1. Executive authority ................................................................................................................... -

Mission Report Zimbabwe Final

THE OBSERVATORY FOR THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS L’O BSERVATOIRE EL OBSERVATORIO pour la Protection des Défenseurs para la Protección de los Defensores de des Droits de l’Homme Derechos Humanos Report International Fact-finding Mission ZIMBABWE: Run up to the March 29 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections - A Highly Repressive Environment for Human Rights Defenders I - Introduction II. Patterns of human rights violations against defenders, including main perpetrators . III. Individual recounts and experiences of human rights defenders A. Human rights defenders of civil and political rights B. Human rights defenders of economic, social and cultural rights C. Cases of repression against journalists human rights defenders IV. Conclusions and recommendations Un programme de la FIDH et de l’OMCT - A FIDH and OMCT venture - Un programa de la FIDH y de la OMCT International Federation of Human Rights 17, Passage de la Main d’Or World Organisation Against Torture 75 011 Paris, France Case postale 21 - 8 rue du Vieux-Billard 1211 Geneva 8, Switzerland March 2008 Content I. INTRODUCTION 1. Delegation’s composition and objectives 2. Historical account of the present situation 3. Context in the run up of the March 29, 2008 harmonised Presidential and Parliamentary elections II. PATTERNS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AGAINST DEFENDERS, INCLUDING MAIN PERPETRATORS . 1. Legal sanction and restrictive legislation 2. Arrest, police assault, acts of torture (sometimes leading to death) and arbitrary detentions 3. Surveillance visits and breakdown of offices 4. Death threats, harassment and acts of intimidation 5. Defamation and media hate propaganda 6. Abductions and disappearances 7. Restriction on public meetings and events 8. -

Kasukuwere, ZYC Under Fire

Kasukuwere, ZYC under fire THE beleaguered Zimbabwe Youth Coun- would legitimise the process. cil (ZYC) has been plunged into turmoil “We will not waste our time trying to get following the Minister of Youth, Indigeni- into this board because we know that the pro- sation and Empowerment Saviour cess is not transparent. We saw how the previ- Kasukuwere’s decision to dissolve the ous board was frustrated when they wanted to ZYC board in December amid revelations carry out their duties so we feel that for as long that the finance committee of the board as the ZYC Act is not amended and is not in was about to institute a probe on ZYC di- tandem with the African Youth Charter, we rector Livingstone Dzikira and his cronies will be wasting our time,” said one youth lead- at the institution. er who requested to be anonymous. Allegations are that he Finance com- However, some youth leaders say that they mittee had for the past year unearthed a are also worried about the role that is being series of fraudulent activities that allegedly played by UNICEF and UNDP in this whole involved Kasukuwere, Dzikira and other circus saying that the two multilateral agencies key council personnel. were wasting money fuelling an institution that Close sources in the board told this is becoming an enemy of young people which reporter Tuesday that the finance commit- they say is not serving any purpose at all. tee had questioned the irregular procure- Meanwhile, all is not well at the troubled ment of furniture delivered to institution with news filtering through to The Kasukuwere’s office by the ZYC using New Age Voices that Dzikira has embarked on funds availed to ZYC for the procurement a clean-up exercise of the Institution where of office furniture by the United Nations those who are deemed unsympathetic to his Development Programme (UNDP).