Chichester Psalms Is a Fascinating Hybrid of Culture, Religion, and Language — It’S a Gloriously Colorful and Unique Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

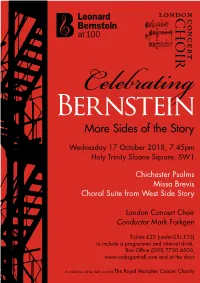

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Seasons/08-09/Chichester Translation.Pdf

In 1965, Leonard Bernstein received a commission from the 1965 Southern Cathedral Festival to compose a piece for the cathedral choirs of Chichester, Winchester, and Salisbury. The result was the three-movement Chichester Psalms, a choral setting of a number of Hebrew psalm texts. This is Bernstein's version of church music: rhythmic, dramatic, yet fundamentally spiritual. The piece opens with the choir proclaiming Psalm 108, verse 2 (Awake, psaltery and harp!). This opening figure (particularly the upward leap of a minor seventh) recurs throughout the piece. The introduction leads into Psalm 100 (Make a joyful noise unto the Lord), a 7/4 dance that fits the joyous mood of the text. At times, this movement sounds like something out of West Side Story - it is percussive, with driving dance rhythms. The second movement starts with Psalm 23, with only a solo boy soprano and harp (suggesting David); the sopranos of the choir enter, repeating the solo melody. Suddenly and forcefully, the men interrupt in the middle of the Psalm 23 text (just after "Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me") with Psalm 2. The setting of this text differs greatly from the flowing melodic feel of Psalm 23; it is evocative of the conflict in the text, with the men at times almost shouting. The men's voices gradually fade, and the initial peaceful melody returns (along with the rest of the Psalm 23 text), with the men continuing underneath. Movement 3 begins with an instrumental introduction based on the opening figure of the piece. The choir then enters with Psalm 131, set in a fluid 10/4 meter. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Leonard Bernstein

chamber music with a modernist edge. His Piano Sonata (1938) reflected his Leonard Bernstein ties to Copland, with links also to the music of Hindemith and Stravinsky, and his Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1942) was similarly grounded in a neoclassical aesthetic. The composer Paul Bowles praised the clarinet sonata as having a "tender, sharp, singing quality," as being "alive, tough, integrated." It was a prescient assessment, which ultimately applied to Bernstein’s music in all genres. Bernstein’s professional breakthrough came with exceptional force and visibility, establishing him as a stunning new talent. In 1943, at age twenty-five, he made his debut with the New York Philharmonic, replacing Bruno Walter at the last minute and inspiring a front-page story in the New York Times. In rapid succession, Bernstein Leonard Bernstein photo © Susech Batah, Berlin (DG) produced a major series of compositions, some drawing on his own Jewish heritage, as in his Symphony No. 1, "Jeremiah," which had its first Leonard Bernstein—celebrated as one of the most influential musicians of the performance with the composer conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony in 20th century—ushered in an era of major cultural and technological transition. January 1944. "Lamentation," its final movement, features a mezzo-soprano He led the way in advocating an open attitude about what constituted "good" delivering Hebrew texts from the Book of Lamentations. In April of that year, music, actively bridging the gap between classical music, Broadway musicals, Bernstein’s Fancy Free was unveiled by Ballet Theatre, with choreography by jazz, and rock, and he seized new media for its potential to reach diverse the young Jerome Robbins. -

Quarter Notes JIM HOGAN, EDITOR MARCH 2020

(ped. simile) Edward Weiss CALIFORNIA YOUTH SYMPHONY CALIFORNIA YOUTH SYMPHONY AddressAddress Service Service Requested Requested Forest Piano Quarter Notes JIM HOGAN, EDITOR MARCH 2020 Quarter Notes MARCH (CONCERT) MADNESS www.newagepianolessons.com Copyright © 2011 Edward Weiss The first three weekends of March offer music lovers some fabulous opportunities to enjoy California Youth Symphony music – concerts in San Mateo, Redwood City and the Sierra Foothills involving four of our stellar ensembles. Check out the details in this issue and be sure to join us for what is sure to be a marvelous musical month. Moderato con rubato MUSIC IN THE MOUNTAINS AND IN THE BAY After our widely acclaimed concert in Grass Valley, CA last season, in conjunction with Music in the Mountains, we are delighted to have been invited to perform there once CALIFORNICALIFORNIA YOUTHA YOUTH SYMPHONY SYMPHONY again. This year’s concert on Sunday, March 8, which will be repeated the following 6 Sunday, March 15 at the San Mateo Performing Arts Center, will mark an historic first LeoLeo Eyla Eylar, Conductorr, Conductor for CYS: for the first time in Maestro Leo Eylar’s 30-year tenure11 as Music Director the orchestra will join forces with a full chorus to perform Leonard Bernstein’s deeply 16 moving and profoundly beautiful choral masterpiece Chichester Psalms. The Music PresentingPresenting the theWorld World Premiere Premiere of of in the Mountains Chorus of over 100 members, under the direction of Maestro Ryan Murray, will collaborate with CYS on both March 8 and 15 as we perform this choral/ CALIFORNIA YOUTH SYMPHONY orchestral gem. -

Summer Chorus Summer Philharmonic

Summer Music 2018 Summer Chorus Summer Philharmonic Dominick DiOrio, Conductor Sam Ritter, Assistant Conductor “Set the Wild Echoes Flying” Psalms and Songs for Voices and Orchestra Joseph Ittoop, Tenor Jennie Moser, Soprano David Smolokoff, Tenor Nathanael Udell, Horn Michael Walker, Countertenor Auer Concert Hall Saturday, July 7, 2018 8:00 p.m. BLANK PAGE Thirty-Sixth Program of the 2018-19 Season _______________________ Summer Music 2018 Summer Chorus Summer Philharmonic Dominick DiOrio, Conductor Sam Ritter, Assistant Conductor “Set the Wild Echoes Flying” Psalms and Songs for Voices and Orchestra Joseph Ittoop, Tenor Jennie Moser, Soprano David Smolokoff, Tenor Nathanael Udell, Horn Michael Walker, Countertenor _________________ Auer Concert Hall Saturday Evening July Seventh Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu “Set the Wild Echoes Flying” Psalms and Songs for Voices and Orchestra Chichester Psalms (1965) ..................... Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) Michael Walker, Countertenor Denique Isaac, Soprano Elise Anderson, Mezzo-Soprano Rodney Long, Tenor Grant Farmer, Baritone I Psalm 108, vs. 2 Urah, hanevel, v’chinor! Awake, psaltery and harp: A-irah shachar I will rouse the dawn! Psalm 100 Hariu l’Adonai kol haarets Make a joyful noise unto the Lord all ye lands. Iv’du et Adonai b’simcha. Serve the Lord with gladness. Bo-u l’fanav bir’nanah. Come before His presence with singing. D’u ki Adonai Hu Elohim. Know ye that the Lord, He is God. Hu asanu, v’lo anachnu. It is He that hath made us, and not we ourselves. Amo v’tson mar’ito. We are His people and the sheep of His pasture. Bo-u sh’arav b’todah, Enter into His gates with thanksgiving, Chatseirotav bit’hilah, And into His courts with praise. -

Riends of Music

CHRIST AND ST. LUKE’S CHURCH 2017/2018 SEASON ACRED MUSIC IN THE LITURGY This year’s liturgical offerings give the best of what the Anglican Tradition has to offer. Special music at our Principal Sunday morning liturgies are highlighted, as well as services of Choral Evensong, often called the Jewel in the Anglican Crown. All events are free-will offering. Sunday, October 1, 4pm Reformation Hymn Festival 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. Join in a hearty afternoon singing hymns of the Christian faith led by chapter organists. Sponsored by the American Guild of Organists and Virginia Wesley- an University. Sunday, October 22, 10:15am Choral Matins and Eucharist for St. Luke’s Day We celebrate our Patronal Feast with a special service of Choral Matins (Morning Prayer) and Eucharist. Sunday, November 12, 6pm Season highlight Fauré Requiem & Bernstein Chichester Psalms On the heels of Leonard Bernstein’s 100th birthday, the Parish Choir presents his Chichester Psalms, as well as Ga- briel Fauré’s beloved Requiem with full orchestra. Sunday, December 3, 5:30pm Advent Lessons & Carols The Parish Choir will lead a candle-lit service of Lessons and Carols, in the tradition of King’s College, Cambridge. Enter the holy season of preparation with this beautiful and meditative service. Christmas Eve, Sunday, December 24, 9:30pm Benjamin Britten’s Ceremony of Carols As the Christmas Eve Carol Prelude, the women of the Parish Choir present Britten’s beloved work with gifted harpist Barbara Chapman. Sunday, January 7, 2018, 5pm Choral Evensong for Epiphany (@St. Paul’s) The Choirs of Christ and St. -

Delve Deeper Discover More About the Cathedral’S 900 Year History, and the Shared Heritage Between Sussex and the US

Delve Deeper Discover more about the Cathedral’s 900 year history, and the shared heritage between Sussex and the US. chichestercathedral.org.uk/american-patrons Explore Chichester Cathedral We hope that we can welcome you to the Cathedral in person, but until then here are some tasters to enjoy from your own home. Complete an online pilgrimage Make an online pilgrimage to The Shrine of St Richard, our own Saint and 13th century Bishop. The Shrine was one of the most important for pilgrims during Medeival times and thousands continue to visit and pray here each year. Click here to make your pilgrimage >> 1 Image: The Shrine of Saint Richard, with the anglo-german tapestry by artist Ursula Benker-Schirmer Page 1 Image: The Cathedral’s Organist & Master of the Choristers Charles Harrison Join us online for Evensong Join us for Evensong and enjoy the exceptional beauty of our Cathedral choir whose 2 singing has a global reputation. We encourage you to find a comfortable position that helps you to pray. Click here to join the service from 3rd March (5.00pm EST) >> Page 2 Did you know? ? Here are just a few of the many historical American links to East and West Sussex for you to explore. Revolution The father of the American Revolution Thomas Paine came from Lewes, East Sussex. Thomas Paine was introduced to Benjamin Franklin by the third Duke of Richmond, whose Goodwood Estate lies just outside of Chichester. The Duke gained the title of the ‘Radical Duke’ reflecting his support for the American Revolution. The Sussex Declaration, a rare copy of the American Declaration of Independence, is held at the West Sussex Archives. -

Celebrating Bernstein Flyer.Pdf

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and Music Director: drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Mark Forkgen include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord Nathan Mercieca is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut countertenor from the score of the musical. Richard Pearce In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in organ medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed Daniel de-Fry it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, harp countertenor soloist and percussion. After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is Sacha Johnson and rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Alistair Marshallsay West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, percussion America and Somewhere. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Leonard

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms: An Analysis and Companion Piece A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Joshua Henry Fishbein 2014 © Copyright by Joshua Henry Fishbein 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms: An Analysis and Companion Piece by Joshua Henry Fishbein Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two parts to this dissertation: the first is an analytical monograph, and the second a music composition, both of which are described below. Part One (Analytical Monograph) In his composition, Chichester Psalms for choir, solo treble, and orchestra, Leonard Bernstein assembles excerpts in Hebrew from the Book of Psalms to narrate a story of conflict and resolution. Bernstein develops his narrative musically by foreshadowing, summarizing, and dramatizing conflict. Specifically, he alludes to key areas in advance of their arrival by manipulating sequential repetition, melodic contour, and ambiguous harmonies. He concisely restates the music he has already presented in an eclectic juxtaposition of keys, textures, and themes. Finally, the composer dramatizes conflict by exploring distant keys at the micro and ii macro levels. The musical application of these devices is notable for the way that it illuminates the meaning of the text. Part Two (Music Composition) Using Bernstein’s music as inspiration, I composed an original Judeo-Christian interfaith companion piece to Chichester Psalms, titled Psalms, Songs, and Blues. In five movements, this piece sets both Psalm excerpts and portions of the Jewish liturgy in English, Hebrew, and Latin, for cantor (baritone), SATB chorus, and orchestra. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Friday 6 November 2015 7.30pm Barbican Hall WYNTON MARSALIS WORLD PREMIERE Bernstein Prelude, Fugue and Riffs Wynton Marsalis Concerto in D (world premiere) London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements Bernstein Chichester Psalms James Gaffigan conductor Nicola Benedetti violin Ben Hill boy treble London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.50pm 2 Welcome 6 November 2015 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. APPLICATIONS OPEN FOR THE 2016 We are delighted to welcome back American PANUFNIK COMPOSERS SCHEME conductor James Gaffigan, following his debut performance with the Orchestra in 2014, for a The LSO Panufnik Composers Scheme is an exciting programme of works by Bernstein, Wynton Marsalis initiative offering six emerging composers each year and Stravinsky. the opportunity to write for and work with a world- class symphony orchestra. It has been devised by The concert opens with Bernstein’s Prelude, Fugue the Orchestra in association with Lady Panufnik in and Riffs for jazz combo and clarinet, in which the memory of her late husband, the composer Sir Andrzej Orchestra’s Principal Clarinet Chris Richards is Panufnik, and is generously supported by the Helen featured. This is followed by the world premiere Hamlyn Trust. of a new Violin Concerto by America’s pre-eminent jazz musician, Wynton Marsalis. Concerto in D was We are now accepting applications for the 2016 composed in close collaboration with violinist scheme. The programme begins in February 2016 Nicola Benedetti – also a great friend of the LSO’s – and culminates with a public workshop in April 2017.