Mcrofilms ]Hteniatloiial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid Into Alabama'

H-Indiana McMullen on Willett, 'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama' Review published on Monday, May 1, 2000 Robert L. Willett, Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999. 232 pp. $18.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57860-025-0. Reviewed by Glenn L. McMullen (Curator of Manuscripts and Archives, Indiana Historical Society) Published on H-Indiana (May, 2000) A Union Cavalry Raid Steeped in Misfortune Robert L. Willett's The Lightning Mule Brigade is the first book-length treatment of Indiana Colonel Abel D. Streight's Independent Provisional Brigade and its three-week raid in spring 1863 through Northern Alabama to Rome, Georgia. The raid, the goal of which was to cut Confederate railroad lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, was, in Willett's words, a "tragi-comic war episode" (8). The comic aspects stemmed from the fact that the raiding force was largely infantry, mounted not on horses but on fractious mules, anything but lightning-like, justified by military authorities as necessary to take it through the Alabama mountains. Willett's well-written and often moving narrative shifts between the forces of the two Union commanders (Streight and Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge) and two Confederate commanders (Col. Phillip Roddey and Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest) who were central to the story, staying in one camp for a while, then moving to another. The result is a highly textured and complex, but enjoyable, narrative. Abel Streight, who had no formal military training, was proprietor of the Railroad City Publishing Company and the New Lumber Yard in Indianapolis when the war began. -

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The Public Historian, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 80-87 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.80 . Accessed: 23/02/2012 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and National Council on Public History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Historian. http://www.jstor.org 80 n THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The American public increasingly receives its history from images. Thus it is incumbent upon public historians to understand the strategies by which images and artifacts convey history in exhibits and to encourage a conver- sation about language and methodology among the diverse cultural work- ers who create, use, and review these productions. The purpose of The Public Historian’s exhibit review section is to discuss issues of historical exposition, presentation, and understanding through exhibits mounted in the United States and abroad. Our aim is to provide an ongoing assess- ment of the public’s interest in history while examining exhibits designed to influence or deepen their understanding. -

16 043539 Bindex.Qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176

16_043539 bindex.qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176 176 B Boston Public Library, 29–30 Babysitters, 165–166 Boston Public Market, 87 Index Back Bay sights and attrac- Boston Symphony Index See also Accommoda- tions, 68–72 Orchestra, 127 tions and Restaurant Bank of America Pavilion, Boston Tea Party, 43–44 Boston Tea Party Reenact- indexes, below. 126, 130 The Bar at the Ritz-Carlton, ment, 161–162 114, 118 Brattle, William, House A Barbara Krakow Gallery, (Cambridge), 62 Abiel Smith School, 49 78–79 Brattle Book Shop, 80 Abodeon, 85 Barnes & Noble, 79–80 Brattle Street (Cambridge), Access America, 167 Barneys New York, 83 62 Accommodations, 134–146. Bars, 118–119 Brattle Theatre (Cambridge), See also Accommodations best, 114 126, 129 Index gay and lesbian, 120 Bridge (Public Garden), 92 best bets, 134 sports, 122 The Bristol, 121 toll-free numbers and Bartholdi, Frédéric Brookline Booksmith, 80 websites, 175 Auguste, 70 Brooks Brothers, 83 Acorn Street, 49 Beacon Hill, 4 Bulfinch, Charles, 7, 9, 40, African Americans, 7 sights and attractions, 47, 52, 63, 67, 173 Black Nativity, 162 46–49 Bunker Hill Monument, 59 Museum of Afro-Ameri- Berklee Performance Center, Burleigh House (Cambridge), can History, 49 130 62 African Meeting House, 49 Berk’s Shoes (Cambridge), Burrage Mansion, 71 Agganis Arena, 130 83 Bus travel, 164, 165 Air travel, 163 Big Dig, 174 airline numbers and Black Ink, 85 C websites, 174–175 Black Nativity, 162 Calliope (Cambridge), 81 Alcott, Louisa May, 48, 149 The Black Rose, 122 Cambridge Common, 61 Alpha Gallery, 78 Blackstone -

PETITION Ror,RECOGNITION of the FLORIDA TRIBE Or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS

'l PETITION rOR,RECOGNITION OF THE FLORIDA TRIBE or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS TH;: FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS and the Administra tive Council, THE NORTHWEST FLORIDA CREEK INDIAN COUNCIL brings this, thew petition to the DEPARTMENT Or THE INTERIOR OF THE FEDERAL GOVERN- MENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, and prays this honorable nation will honor their petition, which is a petition for recognition by this great nation that THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is an Indian Tribe. In support of this plea for recognition THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS herewith avers: (1) THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS nor any of its members, is the subject of Congressional legislation which has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship sought. (2) The membership of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is composed principally of persons who are not members of any other North American Indian tribe. (3) A list of all known current members of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS, based on the tribes acceptance of these members and the tribes own defined membership criteria is attached to this petition and made a part of it. SEE APPENDIX----- A The membership consists of individuals who are descendants of the CREEK NATION which existed in aboriginal times, using and occuping this present georgraphical location alone, and in conjunction with other people since that time. - l - MNF-PFD-V001-D0002 Page 1of4 (4) Attached herewith and made a part of this petition is the present governing Constitution of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEKS INDIANS. -

Funding for Cultural Organizations in Boston and Nine Other Metropolitan Areas

UNDERSTANDING BOSTON Funding for Cultural Organizations in Boston and Nine Other Metropolitan Areas The Boston Foundation Publication Credits Author Susan Nelson, Principal, TDC Additional Research Anne Freeh Engel, TDC Karen Urosevich, TDC Project Coordinator and Editor Ann McQueen, Program Officer, Boston Foundation Editorial Consulting Angel Bermudez, Co-director of Program, Boston Foundation Terry Lane, Co-director of Program, Boston Foundation Design Kate Canfield, Canfield Design Cover Photo: Richard Howard The Boston Lyric Opera’s September 2002 presentation of Bizet’s Carmen attracted 140,000 people to two free performances on the Boston Common. © 2003 by The Boston Foundation. All rights reserved. Contents Preface . 4 Executive Summary. 5 Introduction . 11 CHAPTER ONE What are the Characteristics of Each Cultural Market?. 14 CHAPTER TWO How are Financial Resources Distributed Across the Sector?. 22 Cultural nonprofit institutions with annual budgets greater than $20 million . 24 Cultural organizations with annual budgets between $5 and $20 million . 26 Cultural nonprofit organizations with annual budgets between $1.5 and $5 million. 29 Organizations with budgets between $500,000 and $1.5 million . 32 Organizations with budgets under $500,000. 35 CHAPTER THREE What Types of Contributed Resources are Available? . 38 Government Funding. 39 Foundation Funding. 43 Corporate Funding. 46 Public Funding Strategies in Large Markets. 48 Public Funding Strategies in Small Markets. 49 Individual Giving . 53 CHAPTER FOUR What are the Implications of These Findings? . 54 End Paper . 56 APPENDIX ONE Data Sources Demographic Statistics. i Arts Nonprofit Organizations . ii State Arts Funding. ii Foundation Giving. ii Corporations . iii Local Arts Agencies . iii Literature. iii APPENDIX TWO Local Arts Agencies Boston . -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

Black Pilots, Patriots, and Pirates: African-American Participation in the Virginia State and British Navies During the Revolutionary War in Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Black Pilots, Patriots, and Pirates: African-American Participation in the Virginia State and British Navies during the Revolutionary War in Virginia Kolby Bilal College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bilal, Kolby, "Black Pilots, Patriots, and Pirates: African-American Participation in the Virginia State and British Navies during the Revolutionary War in Virginia" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626268. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4hv4-ds79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLACK PILOTS, PATRIOTS, AND PIRATES African-American Participation in the Virginia State and British Navies During the Revolutionary War in Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Kolby Bilal 2000 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Bilal Approved, April 2000 James Axtell John Sel f U J Ronald Schecter For Michael and all of the other African American navy veterans who preceded him honor, courage, and dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABSTRACT vi INTRODUCTION 2 CHAPTER I 11 CHAPTER II 29 CONCLUSION 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 VITA 47 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Professor James Axtell, under whose guidance this thesis was prepared, for his attempts to make me a better writer. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

1 LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ewis Hayden died in Boston on Sunday morning April 7, 1889. L His passing was front- page news in the New York Times as well as in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald and Boston Evening Transcript. Leading nineteenth century reformers attended the funeral including Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights champion Lucy Stone. The Governor of Massachusetts, Mayor of Boston, and Secretary of the Commonwealth felt it important to participate. Hayden’s was a life of real signi cance — but few people know of him today. A historical marker at his Beacon Hill home tells part of the story: “A Meeting Place of Abolitionists and a Station on the Underground Railroad.” Hayden is often described as a “man of action.” An escaped slave, he stood at the center of a struggle for dignity and equal rights in nine- Celebrate teenth century Boston. His story remains an inspiration to those who Black Historytake the time to learn about Month it. Please join the Town of Framingham for a special exhibtion and visit the Framingham Public Library for events as well as displays of books and resources celebrating the history and accomplishments of African Americans. LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Presented by the Commonwealth Museum A Division of William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Opens Friday February 10 Nevins Hall, Framingham Town Hall Guided Tour by Commonwealth Museum Director and Curator Stephen Kenney Tuesday February 21, 12:00 pm This traveling exhibit, on loan from the Commonwealth Museum will be on display through the month of February. -

2011-Summer Timelines

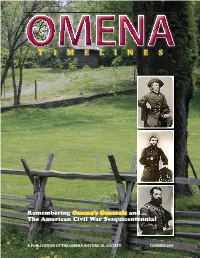

OMENA TIMELINES Remembering Omena’s Generals and … The American Civil War Sesquicentennial A PUBLICATION OF THE OMENA HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2011 From the Editor Jim Miller s you can see, our Timelines publica- tion has changed quite a bit. We have A taken it from an institutional “newslet- ter” to a full-blown magazine. To make this all possible, we needed to publish it annually rather than bi-annually. By doing so, we will be able to provide more information with an historical focus rather than the “news” focus. Bulletins and OHS news will be sent in multiple ways; by e-mail, through our website, published in the Leelanau Enterprise or through special mailings. We hope you like our new look! is the offi cial publication Because 2011 is the sesquicentennial year for Timelines of the Omena Historical Society (OHS), the start of the Civil War, it was only fi tting authorized by its Board of Directors and that we provide appropriately related matter published annually. for this issue. We are focusing on Omena’s three Civil War generals and other points that should Mailing address: pique your interest. P.O. Box 75 I want to take this opportunity to thank Omena, Michigan 49674 Suzie Mulligan for her hard work as the long- www.omenahistoricalsociety.com standing layout person for Timelines. Her sage Timelines advice saved me on several occasions and her Editor: Jim Miller expertise in laying out Timelines has been Historical Advisor: Joey Bensley invaluable to us. Th anks Suzie, I truly appre- Editorial Staff : Joan Blount, Kathy Miller, ciate all your help. -

The American Revolution

The American Revolution The American Revolution Theme One: When hostilities began in 1775, the colonists were still fighting for their rights as English citizens within the empire, but in 1776 they declared their independence, based on a proclamation of universal, “self-evident” truths. Review! Long-Term Causes • French & Indian War; British replacement of Salutary Neglect with Parliamentary Sovereignty • Taxation policies (Grenville & Townshend Acts); • Conflicts (Boston Massacre & Tea Party, Intolerable Acts, Lexington & Concord) • Spark: Common Sense & Declaration of Independence Second Continental Congress (May, 1775) All 13 colonies were present -- Sought the redress of their grievances, NOT independence Philadelphia State House (Independence Hall) Most significant acts: 1. Agreed to wage war against Britain 2. Appointed George Washington as leader of the Continental Army Declaration of the Causes & Necessity of Taking up Arms, 1775 1. Drafted a 2nd set of grievances to the King & British People 2. Made measures to raise money and create an army & navy Olive Branch Petition -- Moderates in Congress, (e.g. John Dickinson) sought to prevent a full- scale war by pledging loyalty to the King but directly appealing to him to repeal the “Intolerable Acts.” Early American Victories A. Ticonderoga and Crown Point (May 1775) (Ethan Allen-Vt, Benedict Arnold-Ct B. Bunker Hill (June 1775) -- Seen as American victory; bloodiest battle of the war -- Britain abandoned Boston and focused on New York In response, King George declared the colonies in rebellion (in effect, a declaration of war) 1.18,000 Hessians were hired to support British forces in the war against the colonies. 2. Colonials were horrified Americans failed in their invasion of Canada (a successful failure-postponed British offensive) The Declaration of Independence A. -

The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: a Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3

THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND U.S. General Services Administration VOL. 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: Burial African York New History and of the Archaeology Biology, Skeletal The THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Volumes of A Synthesis Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc Research, Statistical by Prepared . The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. ISBN: 0-88258-258-5 9 780882 582580 HOWARD UNIVERSITY HUABG-V4-Synthesis-0510.indd 1 5/27/10 11:17 AM THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology, and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. HOWARD UNIVERSITY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 Published in association with the United States General Services Administration The content of this report is derived primarily from Volumes 1, 2, and 3 of the series, The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York. Application has been filed for Library of Congress registration. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. General Services Administration or Howard University. Published by Howard University Press 2225 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite 720 Washington, D.C.