Skateparks: Trace and Culture Volume 1 Skateparks: Trace and Culture Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11816 Asset Report Wonthella.Indd

WONTHELLA SKATEPARK DRAFT SKATEPARK ASSESSMENT REPORT MARCH 2012 WONTHELLA SKATEPARK ASSET REPORT 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS OBJECTIVE 3 WONTHELLA SKATEPARK OVERVIEW 4 SKATEPARK RATING 5 SUMMARY 5 ACTION ITEMS 6 POSSIBLE WORKS 6 LIFE CYCLE 7 RECOMMENDATIONSNSS 8 CONDITION DETAILSETAILS 9 FUNCTION DETAILSETAILS 11 EXAMPLELE PHOTO APPENDIXAPPE 13 EXPLANATIONNATION OF TERMS 19 KEY CRITERIATERIA 20 TERMS - GENERALGEDRAFT ONLY 21 TERMS - PHOTO APPENDIX 22 AUSTRALIAN STANDARDS & OTHER DOCUMENTS 23 DISCLAIMER 25 PREPARED BY CONVIC FOR THE CITY OF GERALDTON WONTHELLA SKATEPARK ASSET REPORT 3 OBJECTIVE THE PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT IS TO ASSESS THE CURRENT CONDITION AND FUNCTIONALITY OF THE SKATEPARK AND HIGHLIGHT AREAS OF CONCERN FOR COMMUNITY AND COUNCIL. THIS ASSESSMENT PRODUCES AN OVERALL SCORE THAT ESTIMATES THE SKATEPARKSARKS REMAINING USEFUL LIFE BASEDASED ONO KEY CRITERIA. Assessing the skateparktepark is essential tto: • Defi nee potential liabilities and hazards. • Understandstand its capacity,capacitcapa condition and how longg it is viable.viabv • Develop aDRAFT regregular maintenance ONLY schedule and long term plan for the skatepark to maximise its value as a community asset. The report gives valuable information to stakeholders and will provide guidance and advice on how to reduce risks and capitalise on opportunities where applicable. PREPARED BY CONVIC FOR THE CITY OF GERALDTON WONTHELLA SKATEPARK ASSET REPORT 4 WONTHELLA SKATEPARK OVERVIEW Wonthella Skatepark is locatedlocate on the arranged at the top of the platform and a corner of Eighth And Pass St, Wonthella, level change forming a long grind ledge. WA. The skateparkkatepark borboborders a large There are shade shelters and seating sporting complexmplex withw pools and various dispersed in 2 refuge areas around the ovals south ofDRAFTf the skatepark. -

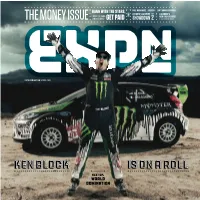

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Etnies Album Download Free Etnies Album Download Free

etnies album download free Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdce05c41a • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdadc384d4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

Skate Catalogue2008

Concrete® Sportanlagen GmbH Skate Catalogue 2008 For the last 50 years Hermann Rudolph Baustoffwerk has been dealing with concrete. Therefore we are claiming to know all about the subtleties of this material. We have Skate Catalogue 2008 more than 150 employees as well as an in-house engi- neering and design department with 18 engineers and technicians. Furthermore we can now take advantage of the extensive experience we gained through design- ing and producing high-class elements for the building industry. This is of great benefit for our leisure facilities. Our leisure facilities are distributed by Concrete ® Spor- tanlagen GmbH. Concrete ® Sportanlagen GmbH www.concrete-skateparks.com www.concrete-sportanlagen.com [email protected] Ellhofen/Steinbißstr. 15 D-88171 Weiler-Simmerberg, Germany Phone +49/8384/8210-90 JAN 2008 DESIGN BY WWW.NZWG.DE Telefax +49/8384/8210-91 Contents General Information 4 Modular Elements 12 Grind Elements 36 Single Ramps 60 Funboxes 72 Run-up and Boundary Elements 96 Miniramps and Halfpipes 112 Pools/Mellows/Volcanoes 118 Accessories 160 General Information Skate Park Planning The most essential thing: the right contact By now Concrete® Skateparks are able to look back on many years of experience in the field of skate and BMX parks. Experience in cooperation with the target groups, the awarded engineering offices, the city councils and the mu- nicipalities shows that the creation of a fantastic and, and as a result also highly frequented, skate park is hardly possible without communication with everyone involved. Not every town planner or architect has the knowledge of what the local roller sportsmen would like to have for their recreational activities. -

{PDF EPUB} Hosoi My Life As a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor by Christian Hosoi from a Jail Cell to a Church

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hosoi My Life as a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor by Christian Hosoi From a jail cell to a church. Long before he was legally old enough to drink, the skateboarder nicknamed “Christ” was a stud on the pro circuit who was touted as an emerging rival to the legendary Tony Hawk. Hosoi’s fame brought him a lot of money, parties and girls, but he also rode his board into a downward spiral of substance abuse that eventually landed him in prison. The skateboarder known for his “Christ Air” move has since reformed himself as a Huntington Beach resident and pastor at The Sanctuary church in Westminster. Now 44, he’s come out with a tell-all autobiography, titled “Hosoi: My Life as a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor.” At 7 p.m. Wednesday, Hosoi will sign copies of his book at Barnes & Noble, 7881 Edinger Ave., No. 110, in the Bella Terra shopping center. In the memoir, Hosoi recounts his life as a youth skateboarder and celebrity. He learned to skateboard at a Marina del Rey skatepark and turned pro at 14. His biggest competition was Hawk, who was around his same age. Hosoi grew close with pro skateboarders Tony Alva and Jay Adams, and graced the cover of Thrasher Magazine several times. Even though he was underage — as he was for most of his career — he could get immediate access to any nightclub. Then he started to drift into drugs. When Hosoi was 8, his father introduced him to marijuana. From there, Hosoi tried “every drug under the sun,” including cocaine, acid, Ecstasy and, eventually, methamphetamine. -

Magazine Subscriptions

Magazine Subscriptions PTP 2707 Princeton Drive Austin, Texas 78741 Local Phone: 512/442-5470 Outside Austin, Call: 1-800-733-5470 Fax: 512/442-5253 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magazinesptp.com Jessica Cobb Killeen ISD Bid for 16-20-06-207 (Magazine Subscriptions) 7/11/16 Purchasing Dept. Retail Item Percent Net Unit Ter Unit No. Discount Price Subscription Title Iss. m Price 0001 5.0 MUSTANG & SUPER FORDS now Muscle Mustangs & Fast Fords 12 1Yr. $ 44.99 30% $ 31.49 0002 ACOUSTIC GUITAR 12 1Yr. $ 36.95 30% $ 25.87 0003 ACTION COMICS SUPERMAN 12 1Yr. $ 29.99 30% $ 20.99 0004 ACTION PURSUIT GAMES Single issues through the website only 12 1Yr. $ - 0005 AIR & SPACE SMITHSONIAN 6 1Yr. $ 28.00 30% $ 19.60 0006 AIR FORCE TIMES **No discount 52 1Yr. $ 58.00 0% $ 58.00 0007 ALFRED HITCHCOCKS MYSTERY MAGAZINE 12 1Yr. $ 32.00 30% $ 22.40 0008 ALL YOU 2015 Dec: Ceased 12 1Yr. $ - 0009 ALLURE 12 1Yr. $ 15.00 30% $ 10.50 0010 ALTERNATIVE PRESS 12 1Yr. $ 15.00 15% $ 12.75 0011 AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 12 1Yr. $ 64.00 15% $ 54.40 0012 AMERICA (National Catholic Weekly) 39 1Yr. $ 60.95 15% $ 51.81 0013 AMERICAN ANGLER 6 1Yr. $ 19.95 30% $ 13.97 0014 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF **No discount 4 1Yr. $ 95.00 0% $ 95.00 0015 AMERICAN BABY 2015 May: Free Online at americanbaby.com 12 1Yr. $ - 0016 AMERICAN CHEERLEADER 6 1Yr. $ 17.95 30% $ 12.57 0017 AMERICAN COWBOY 6 1Yr. $ 26.60 15% $ 22.61 0018 AMERICAN CRAFT 6 1Yr. -

Skating to Success: What an Afterschool Skateboard Mentoring Program Can Bring to PUSD Middle Schoolers

Skating to Success: What an Afterschool Skateboard Mentoring Program Can Bring to PUSD Middle Schoolers Zander Silverman Urban Environmental Policy Senior Comprehensive Project Professor Cha, Professor Matsuoka 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary – 2 Acknowledgements - 3 Introduction - 4 Background - 5 Literature Review - 7 Culture of Skateboarder - 7 Sexism in Skateboarding - 8 Skateboarding and Adolescent Development - 9 Public Perception of Skateboarding - 10 Skateboarding and Struggles for Urban Space - 11 Afterschool Programs - 14 Social Benefits - 14 Educational Benefits - 16 Physical/Health Benefits - 17 Methodology - 22 Research Questions - 22 Participants - 22 Materials - 22 Design and Procedure - 23 Case Study Introduction - 23 Findings - 27 Overview - 27 Benefits of Skateboarding - 28 Sexism in Skateboarding - 30 Skateboarding and Higher Education - 31 Skateboarding and After School Programs - 33 Role of After School Programs - 36 Components/Obstacles to After School Programs - 37 Attitudes Toward Skateboarding Mentoring Program - 38 Analysis - 39 Recommendations - 45 #1.Amend PUSD Policy to Remove Skateboarding from “Activities with Safety Risks” - 45 # 2: Adapt PUSD Policy on Community Partnerships to a Skateboard Mentoring Program - 46 # 3. Remove Skateboarding From Prohibited Activities at Occidental College - 47 #4. Expand the Skateboard Industry’s Support to NGO’s -48 #5. Expand Availability of Certification Methods for Skateboard Programmers - 49 Conclusion - 51 Appendix # 1: Full List of Interviewees and Titles – 53 Appendix # 2: PUSD Policy AR 1330.1 Joint Use Agreements - 54 Appendix # 3: SBA Australia Certification Process – 55 Bibliography - 56 2 Executive Summary The following report discusses the potential of an afterschool skateboard mentoring program that pairs college students with middle schoolers in Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD). -

Subject List - Rbdigital Magazines Subscriptions (March 7, 2017)

Subject List - RBdigital Magazines Subscriptions (March 7, 2017) Architecture Affaires Plus (French) Business Today –Taiwan AD – China Capital France AD - Germany Economist AD - Italia Entrepreneur Magazine Architectural Digest Fast Company Architectural Digest - India Inc. Magazine Architectural Digest - Mexico Kiplinger's Personal Finance Rotman Art & Photography Children Aperture Artist’s Magazine National Geographic Kids ARTnews National Geographic Little Kids Digital Photo Digital Photo Pro Digital SLR Photography Chinese Language Drawing Drawing: The Complete Course AD China Juxtapoz: Art & Culture Magazine Business Today – Taiwan Outdoor Photographer Common Health Magazine – Taiwan Photoshop Creative Cosmopolitan – Hong Kong PleinAir Elegant Beauty - Taiwan Popular Photography Elle - Taiwan Queen’s Quarterly Esquire - Taiwan Shutterbug Evergreen – Taiwan Wallpaper GQ - China Watercolor Artist Global Views Monthly – Taiwan Harper’s Bazaar – Hong Kong Bridal Health 2.0 – Taiwan Marie Claire – Hong Kong Marie Claire - Taiwan Brides Men’s Uno - Taiwan Destination Weddings & Honeymoons Mombaby - Taiwan The Knot Weddings Magazine Next Magazine – Taiwan Martha Stewart Weddings Or - China Rhythms Monthly – Taiwan Business Ryori - Taiwan Scientific American – China Adweek Supertaste – Taiwan 1 Computers Handcrafted Jewelry Handwoven Apple Magazine Interweave Crochet Computer Music Interweave Knits Game informer Jewelry Stringing Gamesmaster Knit & Spin GamesTM Knitscene iPhone Life Knitter MacLife Knitting & Crochet from Woman’s Weekly -

So You Think You're As Good As the Dudes That Go on King of the Road? Well, Now's Your Time to Step Up: Thrasher Magazine'

So you think you’re aS good as the dudes that go on King of the Road? Well, now’s your time to step up: Thrasher magazine’s King of the Rad At-Home Challenge is your chance to bust and film the same tricks that the pros are trying to do on the King of the Road right now. The four skaters who land the most tricks and send us the footage win shoes for a year from Etnies, Nike SB, C1RCA, and Converse. You’ve got until the end of the King of the Road to post your clips—Monday, Oct 11th, at 11:59 pm. THE RULES King of the Rad Rules Contestants must film and edit their own videos The individual skater who earns the most points by landing and filming the most KOTR tricks, wins Hard tricks are worth 20 points Harder tricks are worth 30 points Hardest tricks are worth 50 points Fucked-Up tricks are worth 150 points (not available for some terrain) You can perform tricks from any category. The most points overall wins The top four skaters will be awarded the prize of free shoes for a year (that’s 12 pairs) from Nike SB, Converse, Etnies, and C1RCA All non-professional skaters are eligible to compete Deadline for posting footage is Oct. 11th, 11:59 pm Judging will be done by Jake Phelps, & acceptance of sketchy landings, etc will be at his discretion Meet the challenges to the best of your abilities and understanding. Any ambiguities in the wording of the challenges are unintentional. -

Klipsun Magazine, 2010, Volume 40, Issue 04-Spring

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Klipsun Magazine Western Student Publications Spring 2010 Klipsun Magazine, 2010, Volume 40, Issue 04 - Spring Allison Milton Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Milton, Allison, "Klipsun Magazine, 2010, Volume 40, Issue 04 - Spring" (2010). Klipsun Magazine. 251. https://cedar.wwu.edu/klipsun_magazine/251 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Klipsun Magazine by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDITOR'S NOTE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Allison Milton MANAGING EDITOR Gabrielle Nomura COPY EDITOR Stephanie Castillo STORY EDITORS Megan Brown Amy Sanford JillianVasquez ONLINE EDITOR Kelsey Sampson DESIGNERS Audrey Dubois-Boutet Rebecca Rice Lauren Sauser Dear Reader, PHOTO EDITOR Angelo Spagnolo You may not realize it, or acknowledge it in any way, but you re doing it right now. Your eyes are going LEAD PHOTOGRAPHER from right to left as you read these words. Time is passing, Cejae Thompson the clock is ticking and somewhere in the world, someone is fighting for social justice and maybe even for his or her PHOTOGRAPHERS right to party. Reiko Endo Movement. It s not just a physical action. Of course, Brooke Loisel movement is incorporated into our workouts and daily Rhys Logan routines. We move from one place to another. We move Madeline Stevens up in the professional world. And we even move our hips Skyler Wilder when Shakira tells us they don’t lie. -

I. Race, Gender, and Asian American Sporting Identities

I. Race, Gender, and Asian American Sporting Identities Dat Nguyen is the only Vietnamese American drafted by a National Football League team. He was an All-American at Texas A & M University (1998) and an All-Pro for the Dallas Cowboys (2003). Bookcover image: http://www.amazon.com/Dat-Tackling-Life-NFL-Nguyen/dp/1623490634 Truck company Gullwing featured two Japanese Americans in their platter of seven of their “hottest skaters,” Skateboarder Magazine, January 1979. 2 Amerasia Journal 41:2 (2015): 2-24 10.17953/ aj.41.2.2 Skate and Create Skateboarding, Asian Pacific America, and Masculinity Amy Sueyoshi In the early 1980s, my oldest brother, a senior in high school, would bring home a different girl nearly every month, or so the family myth goes. They were all white women, punkers in leath- er jackets and ripped jeans who exuded the ultimate in cool. I thought of my brother as a rock star in his ability to attract so many edgy, beautiful women in a racial category that I knew at the age of nine was out of our family’s league. As unique as I thought my brother’s power of attraction to be, I learned later that numerous Asian stars rocked the stage in my brother’s world of skateboarding. A community of intoxicatingly rebellious Asian and Pacific Islander men thrived during the 1970s and 1980s within a skater world almost always characterized as white, if not blatantly racist. These men’s positioning becomes particularly notable during an era documented as a time of crippling emas- culation for Asian American men. -

Oral History Interview with Ken Block, Professional Rally Driver, Hoonigan Racing

Transcript for: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH KEN BLOCK, PROFESSIONAL RALLY DRIVER, HOONIGAN RACING Accession 2021.48 Interview conducted 12 November 2019 Hoonigan Racing Park City, Utah Interviewers: Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, The Henry Ford Source: KenBlock-Full-Interview.mp4 Running Time: 01:04:49 1 The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org TIME IN COMMENT 00:00 Graphic 00:05 Matt Anderson My name is Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. Today is November 12th, 2019. We are with Ken Block in his uh, shop out of Park City, Utah. Thank you very much for making the time for us today and uh, we’ll start with just a few uh, warm-up questions to kind of get things going. First of all, what’s your favorite kind of music? 00:25 Ken Block Wow, uh, starting off light, huh? [laughter] Uh well I grew up in the ’80s, so I grew up listening to punk rock and new wave, so the current version of that would be called alternative rock, but I also grew up loving hip hop and rap, so I still listen to that too, not as much though. 00:47 Matt Anderson Do you have a favorite movie? 00:50 Ken Block Another tough one, jeez! Uh, it used to be Blazing Saddles, but that isn’t as PC anymore. So uh, I don’t know. Something odd I guess comes to mind something like Fight Club. Yeah something like that.