Volume 12 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

Yeshiva University • Rosh Hashana To-Go • Tishrei 5769

1 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY • ROSH HASHANA TO-GO • TISHREI 5769 Dear Friends, ראש השנה will enhance your ספר It is my sincere hope that the Torah found in this virtual (Rosh HaShana) and your High Holiday experience. We have designed this project not only for the individual, studying alone, but also for a a pair of students) that wishes to work through the study matter together, or a group) חברותא for engaged in facilitated study. להגדיל תורה With this material, we invite you, wherever you may be, to join our Beit Midrash to enjoy the splendor of Torah) and to discuss Torah issues that touch on) ולהאדירה contemporary matters, as well as issues rooted in the ideals of this time of year. We hope, through this To-Go series, to participate in the timeless conversations of our great sages. בברכת כתיבה וחתימה טובה Rabbi Kenneth Brander Dean, Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future Richard M Joel, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Kenneth Brander, Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Robert Shur, General Editor Ephraim Meth, Editor Copyright © 2008 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 413, New York, NY 10033 [email protected] • 212.960.5400 x 5313 2 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY • ROSH HASHANA TO-GO • TISHREI 5769 Table of Contents Rosh Hashana 2008/5769 The Mitzvah of Shofar: Who’s Listening? Rabbi Reuven Brand The Teshuvah Beyond Teshuvah Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman Rosh HaShanah's Role as the Beginning of a New Fiscal Year and How It Affects Us Rabbi Josh Flug Aseret Yemei Teshuva: The Bridge Between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur Rabbi Shmuel Hain The Music of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Selected Minhagim of Rosh Hashana Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer The Personal and Collective Journey to Har haMoria Mrs. -

2020 Appendixes

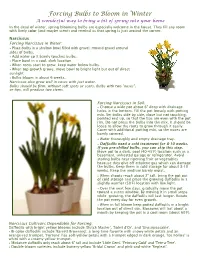

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

The Vasa Star

THETHE VASA VASA STAR STAR VasastjärnanVasastjärnan PublicationPublication of of THE THE VASA VASA ORDER ORDER OF OF AMERICA AMERICA JULY-AUGUSTJULY-AUGUST 2010 2010 www.vasaorder.comwww.vasaorder.com MEB-E Art Björkner MEB-W Ed Netzel MEB-M Sten Hult MEB-S Ulf Alderlöf MEB-C Ken Banks VGS Gail Olson GS Joan Graham VGM Tore Kellgren GM Bill Lundquist GT Keith Hanlon The Grand Master’s Message Bill Lundquist Dear Vasa Brothers and Sisters, they were when we were founded in 1896, promoting our cul- I humbly and proudly accept the most prestigious office as tural heritage and providing a program of social fellowship. Grand Master of the Vasa Order and thank you for graciously We have suffered losses by death but many from lack of inter- electing me. I assume this office with excitement and much est. I plan to put programs in place to give you ideas to help enthusiasm but well aware of the challenges ahead. I am keep your current members interested and active as well as grateful and truly appreciative of your confidence in my ability make more interesting to potential members. New members to lead the Order for the next four years. I pledge to you that I bring in new enthusiasm, new ideas and new workers. will do my utmost to fulfill the goals I have set for this term. Scandinavians are no strangers to challenges. One such These include but are not limited to goals in the following challenge for all of us over the next four years is the reduced areas: Improvement in transparency between the Grand Lodge budget to The Vasa Star. -

Purifying the Impure?

בס“ד Parshiyot Shemini/Parah 23 Adar II, 5779/March 30, 2019 Vol. 10 Num. 30 (#408) This issue is sponsored by the families of Irwin, Jim and David Diamond in memory of their father, Morris Diamond z”l לזכר ולעילוי נשמת אבינו מורינו ר‘ משה בן דוד שלמה ז“ל Purifying the Impure? Ezer Diena In delineating the rules of purity and 1: The student may be right Rabbi Abulafia’s characterization of this impurity, the Torah warns us very According to Rabbeinu Tam (cited in person as one who is able to overcome a strongly to avoid defiling ourselves by Tosafot to Eruvin and Sanhedrin ibid.), challenge can be further split into two eating or otherwise coming into the student and judge meant to prove tests: the logical, and emotional. contact with the carcasses of only that a sheretz would not cause s her atz i m, literally “creeping impurity if an olive-sized piece were One test is to see a Torah ruling which creatures” [singular: sheretz]. (Vayikra transported, and this may have basis in seems illogical, even by the Torah’s 11:29-38, 41-44) Not only that, but the traditional sources. The ability to permit standards. Certain laws relating to sheretz gained special status as the a sheretz in this way simply indicates purity and impurity may very well fall paradigm of uncleanliness in the detailed knowledge and halachic into this category! In fact, one of the Talmud (Taanit 16a): acumen. However, other commentaries more challenging details of ritual purity, raise technical halachic questions which we read about in Parshat Parah “Rabbi Adda bar Ahavah said: A against this approach, and reject it. -

The Best Part of Waking up Birchas Hatorah on Shavuos Morning Rabbi Shmuel Maybruch Faculty, Stone Beit Midrash Program

The Best Part of Waking Up Birchas HaTorah on Shavuos Morning Rabbi Shmuel Maybruch Faculty, Stone Beit Midrash Program The Importance of Birchas HaTorah One of the most significant berachos we recite throughout the day is the birchas haTorah. This series of berachos30 is not only a halachic requirement, but a powerful testament to the importance of Torah study. For example, the Talmud (Nedarim 81a) asks why Torah scholarship often does not pass from a father who is a Torah scholar to his children. Ravina explains that it is result of the scholar’s omission of birchas haTorah: ומפני מה אין מצויין ת"ח לצאת Why is it uncommon for Torah scholars to produce Torah scholars as ת"ח מבניהן? רבינא אמר... their children? Ravina said: Because they [the Torah scholars] do שאין מברכין בתורה תחלה. not recite the berachos [of birchas haTorah] prior [to studying Torah] The Beis Yosef (O.C. 47) quotes his Rebbi, Rabbeinu Yitzhak Abohav, who explains Ravina’s intent: ורבינו הגדול מהר"י אבוהב ז"ל Our great Rebbi, Mahar"i Abohav zt"l, wrote that the [explanation כתב שהטעם שאינם זוכים of the] reason [given by the Talmud] that they are not privileged to לבנים תלמידי חכמים מפני שאין have children that are Torah scholars “because they do not recite the מברכין בתורה הוא לפי שמאחר beracha [of birchas haTorah]” is that since they do not recite שאין מברכין על התורה מורה berachos on the Torah, it demonstrates that they are not studying it שאין קורין אותה לשמה אלא for its own sake, rather merely like a common occupation. -

Cultivating a Jewish Tax Ethic

ARI HART Civilization’s Price: Cultivating a Jewish Tax Ethic Introduction SUPREME COURT JUSTICE Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. famously wrote that taxes are “the price of civilization”. Judaism recognizes them as more. Taxes are a means of civilization, and their creation and collection reveals a tremendous amount about a society’s priorities and values. Recent scandals involving Jews shirking their tax responsibilities have led to much ink being spilled, in certain circles, on whether or not Jew must pay taxes. The Jewish ethical answer in a free democracy is unequivocally “yes”. 1 Does the Jewish ethical tradition have anything to say beyond this basic question? Aside from how they should be paid (regularly, fully), can we artic - ulate a Jewish tax ethic? The Torah contains several kinds of taxes and tithes in its economic sys - tem. p Terumah was levied to support the priests who did not own prop - erty and devoted themselves to the communal good including running the Temple. Terumah, was given, according to rabbinic mandate at a level of between a fortieth, fiftieth or sixtieth of total produce, depending on the generosity of the payer. p Ma’aser rishon , a tenth taken after terumah was taken, was given to support the landless Levi’im in their service educating and serving the Jewish people. RABBI ARI HART is Assistant Rabbi at the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale and Director of Recruitment at Yeshivat Chovevei Torah. 78 Ari Hart 79 p Ma’aser sheini is a share of produce that had to be eaten in the capital, Jerusalem, or sold and substituted with food bought in Jerusalem, to support its economy. -

Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Grimoire University Publications Spring 2005 Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005" (2005). Grimoire. 14. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grimoire by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. spring 2005 volume 4 4 fetter from the editress “Staring at the blank page before you, Open up the dirty window, Let the sun illuminate the words that you could not find...” Each time the lyrics of Natasha Bedingfield’s “Unwritten” play over in my head, I can’t help but be reminded of the seemingly unattainable goals I dream up for myself every day. Not just the dream, but also the struggle to make those visions real— to voice the words and feelings that no one else can— quickly becomes more tiring and frustrating than life itself. Compared to the size of the whole, the simple goal of being published in this unknown, student-run maga zine is but a small accomplishment. This becomes obvious, as this book may eventually (and most likely will) pass from your hand, the reader’s, to the ground, or a trashcan, or— if we’re lucky— tossed out of a third-story dorm window. But the Grimoire is more than just a magazine— it’s a monument on which is carved the legacy of hundreds of students. -

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the Inner Circle of DWP

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the inner circle of DWP There is no better way to reflect on the year passing us by and celebrate the start of a new one, quite like the kick-off of an impossible-to-resist portal to all things luxe and beautiful. The launch of the DWP - Insider editorial portfolio is exactly that. I find myself diving into the fascinating dynamics of two luxury industries, that rake in billions of dollars a year- weddings and travel. If you've found yourself staring down the barrel of done- and-dusted wedding trends, filled with nothing but aspirations to be innovative and different, then we've got your back. We have worked hard to create a platform that hand-picks the best in the business, scouting the most coveted frontrunners to become a ‘go-to’ journal for not only the bride and groom, but the entire bridal squad and all high-life aficionados. This inevitable next step in the Destination Wedding Planner Congress journey, takes an in- depth approach to the glamorous side of the luxury wedding industry - the elite ceremonies, the opulent jewelry and couture, and that of lavish destinations and their unique décor, food and wellness offerings. With each digital post and each bi-annual issue, we reveal the jewels in this season’s bridal crown– all perfectly bound in a must-have journal, that aims to connect partners and advertisers with select clientele; and enrich the reader culturally. Aishwarya Tyagi Editor, Destination Wedding Planner- Insider [email protected] The Reader Wedding Planners Wedding budgets and Brides-to-be ranging from from 65+ countries. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, Ceremonial obJeCts & GraphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, nov ember 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 61 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, GR APHIC & CEREMONIAL A RT INCLUDING A SINGULAR COLLECTION OF EARLY PRINTED HEBREW BOOK S, BIBLICAL & R AbbINIC M ANUSCRIPTS (PART II) Sold by order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th November, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th November - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 16th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Sempo” Sale Number Sixty Six Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky (Consultant) Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

ON the MITZVOT of NON-JEWS: an ANALYSIS of AVODAH ZARAH 2B-3A Rabbi Dov Linzer

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 25 Rabbi Dov Linzer is the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School and the Chair of the Yeshiva’s Departments of Talmud and Jewish Law. ON THE MITZVOT OF NON-JEWS: AN ANALYSIS OF AVODAH ZARAH 2B-3A Rabbi Dov Linzer I. THE SUGYAH Non-Jews are commanded to observe the seven Noahide laws.1 A logical corollary of this is that they are to be rewarded for their performance of these mitzvot, and held liable for transgressing them.2 This assumption, however, is brought into question by the sugyah around the statement of Rav Yosef in Avodah Zarah 2b-3a (paralleled in Bava Kama 35a): 1 Tosefta Avodah Zarah 8:4; Sanhedrin 74b 2 The idea of a world of future reward and punishment for non-Jews is consistent with the position that righteous non-Jews have a portion in the World-to-Come (Tosefta Sanhedrin 13:2; Sanhedrin 105a). It is prima facie difficult to understand how the opposing position, that even the righteous amongst the non-Jews has no share in the World-to-Come, can explain the significance of Noahide mitzvot for a non-Jew. The answers to this question are beyond the scope of this paper, but we can immediately sug- gest three possible solutions: (1) The phrase “World-to-Come” may not refer to the totality of future metaphysical reward, but only one aspect of it; (2) The primary focus of the Noahide laws might be to enforce behavior on this world and do not suggest a meta- physical religious system for non-Jews and (3) While assured no future reward, non-Jews might suffer different degrees of punishment for the degree of their transgressions.