Rabbit-Proof Fence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 04/14 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 04/14 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 339 - Mai 2014 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 04/14 (Nr. 339) Mai 2014 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, ben, sondern auch den aufwändigen liebe Filmfreunde! Proben beizuwohnen und uns ausführ- lich mit Don Davis zu unterhalten. Das Wenn Sie sich in den letzten Wochen gesamte Bild- und Tonmaterial, das gefragt haben, warum wir nur sehr ein- dabei entstanden ist, hat eine Größe geschränkt telefonisch erreichbar wa- von über 100 Gbyte und wird in den ren, dann finden Sie die Antwort auf nächsten Wochen in ein Video umgear- dieser Seite. Nicht nur hielt uns die beitet, das nach Fertigstellung natür- jährlich stattfindende FMX in Atem, lich auf unserem Youtube-Kanal abruf- sondern auch noch ein Filmmusik-Kon- bar sein wird. zert der besonderen Art. Und da aller guten Dinge bekanntlich Doch zunächst zur FMX. Hierbei han- drei sind, haben wir die Gelegenheit delt es sich um einen Branchentreff der genutzt, den deutschen Kameramann Visual Effects Industrie, der jedes Jahr Alexander Sass bei seinem Kurzbesuch Oben: Hollywood-Produzent Jon Landau Unten: Hollywood-Produzent Chris DeFaria renommierte VFX-Spezialisten in die in Stuttgart vor unsere Kamera zu ho- schwäbische Hauptstadt holt. Diese len. Was er uns erzählte und auch den Spezialisten präsentieren dort im Haus Zuschauern bei der Sondervorführung der Wirtschaft ihre neuesten Arbeiten seines neuesten Films FASCINATING und geben damit tiefe Einblicke in die INDIA 3D, können Sie demnächst auf Welt der visuellen Effekte. -

Phillip Noyce by : INVC Team Published on : 28 Nov, 2011 12:10 AM IST

The Indian market has opened up to global movies and the acceptability of international projects has flourished - Phillip Noyce By : INVC Team Published On : 28 Nov, 2011 12:10 AM IST INVC,, Goa,, Acclaimed Australian film director Phillip Noyce has said that the Indian market has opened up to global movies and the acceptability of international projects has flourished here. He stated that cinema has progressed by leaps and bounds across the world and it was really heartening to see its growing reach in a country as diverse as India. Addressing a press conference here today, director Phillip Noyce spoke about his movies and the inspiration which lead him to the art of filmmaking. The master film director who is best known for his much acclaimed movies like ‘Clear and Present Danger’, ‘The Bone Collector’, ‘Newsfront’ and others talked about his life, his motivation to create cinematic masterpieces and what he intends to present to the audience in the future. Phillip Noyce is one of the most famous cinematic directors of the Australian Film Industry. A master of espionage films, Noyce is best known for movies like ‘Newsfront’ which won the Australian Film Institute (AFI) awards for Best Film, Director and Screenplay along with ‘Rabbit-Proof Fence’ which won the Australian Film Institute (AFI) Award for the Best Film in 2002. Noyce has been one of the most successful Australian film directors in Hollywood and has been much acclaimed for his ventures in the American Film Industry. Films like ‘Dead Calm’ which released in 1989 turned Nicole Kidman into a star, the 1994 Tom Clancy spy thriller ‘Clear and Present Danger’ starring Harrison Ford, ‘The Quiet American’- a 2002 film which gave Michael Caine an Academy Award Best Actor nomination and the 2010 action thriller ‘Salt’ starring Angelina Jolie, have all stamped Phillip Noyce’s position as one of the most bankable Australian directors in Hollywood. -

The Bone Collector (1999) Directed by Phillip Noyce

Lincoln, Lincoln, I’ve Been Thinkin’ By Fearless Young Orphan The Bone Collector (1999) Directed by Phillip Noyce A casual viewing of The Bone Collector will probably provide an entertaining movie experience. There are big stars (Denzel Washington, Angelina Jolie, Queen Latifah, Ed O’Neill), there is a sexy plot (serial killer investigations are always sexy plots) and there is an interesting twist on the mix. Washington plays Lincoln Rhyme, an expert forensic detective, textbook author, and decorated cop, who is now paralyzed from the neck down and must do all his detective work from a hospital bed surrounded by high-tech equipment. There is something of Rear Window in this, and something of Silence of the Lambs, in the way he takes a young cop under his wing and grooms her for forensics. Really, what could I have to complain about? Oh, lots. Lots and lots. I’ve seen it twice now. I hated it the first time I saw it. On the second viewing, for purposes of creating a Chunk, I found myself more disappointed in its missed potential than actively hating what it put on screen. Still, that’s enough to Chunk about. Let’s begin! 1. The Serial Killer. I realize I’m coming at this from the back end. Of course we don’t know until the last ten minutes who the killer is and why he’s killing. Naturally, because this is a movie, he is someone we’ve already come to know in the movie’s context. That way, it’s a shocking twist! Yeah, he’s been skulking around Lincoln’s apartment the entire time. -

Download (277Kb)

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This chapter presents the introduction of the research. It describes background of the study, literature review, limitation of the study, problem statement, objective of the study, benefit of the study, research method and research paper organization. A. Background of the Study Human beings were born with the two kinds of sex, male and female. Actually the term male and female in society has a different way since they were born, either physically or habits. People have basic trust that male have to be strong, powerful, and think rationally while female is powerless, emotional, and weaker than male. Its differences and also the patriarchal line that held in society automatically make the different treatments to the two sexes. Today not only man has courage, but also the woman. How the woman fights against injustice and criminal with her courage will be the fact that woman shows her powerful. Actually courage is the mental and moral strength to venture, persevere, and withstand danger, fear, or difficulty (www.wikiepedia.com). An action is courageous if it is an attempt to achieve an end despite penalties, risks, costs, or difficulties of sufficient gravity to deter most people. Similarly a state such as cheerfulness is courageous if it is sustained in spite of such difficulties. A courageous person is 1 2 characteristically able to attempt such actions or maintain such states. For Aristotle, courage is dependent on sound judgment, for it needs to be known whether the end justifies the risk incurred. Similarly, courage is not the absence of fear (which may be a vice), but the ability to feel the appropriate amount of fear; courage is a mean between timidity and overconfidence. -

167558354.Pdf

ngelina Jolie (/dʒoʊˈliː/ joh-LEE, born Angelina Jolie Voight; June 4, 1975) is an American actress, film director, and screenwriter. She has received an Academy Award, two Screen Actors Guild Awards, and three Golden Globe Awards, and was named Hollywood's highest-paid actress by Forbes in 2009 and 2011.[2][3] Jolie promotes humanitarian causes, and is noted for her work with refugees as a Special Envoy and former Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). She has often been cited as the world's "most beautiful" woman, a title for which she has received substantial media attention.[4][5][6][7] Jolie made her screen debut as a child alongside her father Jon Voight in Lookin' to Get Out (1982), but her film career began in earnest a decade later with the low-budget production Cyborg 2 (1993). Her first leading role in a major film was in the cyber- thrillerHackers (1995). She starred in the critically acclaimed biographical television films George Wallace (1997) and Gia (1998), and won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in the drama Girl, Interrupted (1999). Jolie achieved wide fame after her portrayal of the video game heroine Lara Croft in Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), and established herself among the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood with the sequel The Cradle of Life (2003).[8] She continued her action star career with Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005), Wanted (2008), and Salt (2010)—her biggest live-action commercial successes to date[9]—and received further critical acclaim for her performances in the dramas A Mighty Heart (2007) and Changeling (2008), which earned her a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actress. -

Phillip Noyce: Director of Many Moods

E-CineIndia April-June 2020 ISSN: 2582-2500 Article Ranjita Biswas Phillip Noyce: Director of Many Moods Rabbit Proof Fence Celebrated Australian director Phillip Noyce Noyce’s obsession with the moving imag- cannot be boxed into a particular ‘genre’ of es began when he was introduced to ‘under- filmmaking. On one hand, he made block- ground’ (as opposed to Hollywood big studio busters in Hollywood like The Quiet Ameri- films and its distribution network and made can with Michael Caine, The Bone Collector more as personal expression by passionate with Angelina Jolie, etc. and then back in his followers of cinema) short films in 1968 made homeland he made Rabbit Proof Fence, a tale by a group of young Australian filmmakers of human tenacity based on a true story of under the Ubu banner on a shoe-string bud- three Aborigine girls escaping from a deten- get. As Noyce recalls, after watching their tion camp when the then Australian govern- seventeen short films which he attended more ment set up these to ‘educate’ and ‘civilize’ out of curiosity and expectation to enjoy some the indigenous people of mixed parentage ‘vicarious thrills’ as the ‘underground’ term with white fathers. This film was screened, connoted, he was stunned by the experience. along with his other works, at the 24th Kol- ‘On that night I guess my whole attitude to kata International Film Festival (2018) when art, my whole attitude to movies-in fact my Australia was the focus country. Noyce was whole life-changed’, thinking, ‘I’m gonna present at the festival and conducted a couple make movies like that. -

RABBIT-PROOF FENCE Aua Strali , 2002Z Phillip Noyce

RABBIT-PROOF FENCE AUA straLI , 2002Z Phillip NOYCE SYNOPSIS Based on Doris Pilkington’s autobiographical book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, this film is the true story of three Aboriginal girls who are forcibly taken from their families in 1931 to be trained as domestic servants as part of official Australian government policy. Gracie and Daisy cling to Molly for support, and Molly decides they need to return to their parents. Molly plans a daring escape, and the three girls begin an epic journey back to Western Australia, travelling 1,500 miles on foot with no food or water, and navigating by following the fence that has been build across the nation to stem an over-population of rabbits. For days they walk north, following the fence and eluding their pursuers, a native tracker and the regional constabulary. DIRECTOR’s BIOGRAPHY Noyce was born in Griffith, New South Wales, attended Barker College, Sydney, and began making short films at the age of 18, starting with Better to Reign in Hell, using his friends as the cast. He joined the Australian Film & Television School in 1973, and released his first professional film in 1977. Many of his films feature espionage, as Noyce grew up listening from his father’s stories with the Z Special Force during World War II, and has an interest in the theme. After his debut feature, the medium-length Backroads (1977), Noyce achieved commercial and critical success with Newsfront (1978), which won Australian Film Institute (AFI) awards for Best Film, Director, and Screenplay. Noyce worked on two miniseries for Australian television with fellow Australian filmmaker George Miller: The Dismissal (1983) and The Cowra Breakout (1984). -

Movie Talk and Chinese Pirate Film Consumption from the Mid-1980S to 2005

International Journal of Communication 6 (2012), 501–529 1932–8036/20120501 Broadening the Scope of Cultural Preferences: Movie Talk and Chinese Pirate Film Consumption from the Mid-1980s to 2005 ANGELA XIAO WU Northwestern University How do structural market conditions affect people’s media consumption over time? This article examines the evolution of Chinese pirate film consumption from the mid-1980s to 2005 as a structurational process, highlights its different mechanisms (as compared to those of legitimate cultural markets), and teases out an unconventional path to broadening the scope of societal tastes in culture. The research reveals that, in a structural context consisting of a giant piracy market, lacking advertising or aggregated consumer information, consumers developed “movie talk” from the grassroots. The media environment comprised solely of movie talk guides people’s consumption of films toward a heterogeneous choice pattern. The noncentralized, unquantifiable, and performative features of movie talk that may contribute to such an effect are discussed herein. Introduction Literatures in both cultural sociology and communication endeavor to explain cultural preferences. Current research concerns mainly cross-sectional studies with individuals as the unit of analysis (Griswold, Janssen, & Van Rees, 1999; Webster, 2009). The majority of extant theories focus on linking cultural consumption patterns to individual consumers’ psychological predispositions (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974) or socioeconomic statuses (Bourdieu, 1984; Van Rees & Van Eijck, 2003). However, chronological changes in the consumption patterns are relatively underexplored (Tepper & Hargittai, 2009, pp. 227–228). For instance, longitudinal research of the formative role of structured I am grateful to Joseph Man Chan, Jennifer Light, Eszter Hargittai, James Webster, Wendy Griswold, Janice Radway, and Elizabeth Lenaghan for their generous and helpful comments. -

Rabbit-Proof Fence

Rabbit-Proof Fence Rabbit-Proof Fence Film Guide Brendan Maher freshfilmfestival Rabbit-Proof Fence Rabbit Proof Fence Introduction received Dead Calm in 1989. The film Director Philip Noyce Set in 1930’s Australia, Rabbit Proof featured Nicole Kidman and Sam Neill. Australia - USA/90 mins/2002/Colour Fence details the true story of a nine Noyce continued to work in the week trek made by three Aboriginal thriller genre with films such as Sliver girls from the adoptive state home (1993) and The Saint (1997). His two Cast where they were forcibly taken, films from Tom Clancy’s books Patriot Everlyn Sampi Molly Craig back to their family home. Philip Games (1992) and Clear and Present Tianna Sansbury Daisy Kadibill Noyce’s film tells us of a generation of Danger (1994) were generally well Laura Monaghan Gracie Fields Aboriginal children who, because of received. In advance of making Rabbit David Gulpilil Moodoo State Law in Australia, were removed Proof Fence, he said: Ningali Lawford Maud from their homes in order to be “After ten years in Hollywood, I’m still an Myarn Lawford Molly’s Grandmother re-educated and assimilated into outsider, a migrant guest worker telling Deborah Mailman Mavis the white community. Rabbit Proof other people’s stories. As a citizen of the Jason Clarke Constable Riggs Fence recounts the bravery of these world, without nationality, I’ve become the Kenneth Branagh A.O. Neville individual children whilst also depicting ultimate Hollywood foot soldier, directing Natasha Wanganeen the social and political views which action/adventure, escapist stories designed Nina, Dormitory Boss caused their flight. -

YEAR in REVIEW Celebrating Australian Screen Success and a Record Year for AFI | AACTA YEAR in REVIEW CONTENTS

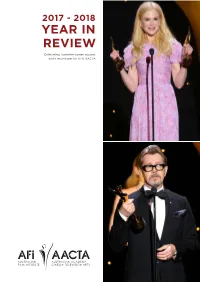

2017 - 2018 YEAR IN REVIEW Celebrating Australian screen success and a record year for AFI | AACTA YEAR IN REVIEW CONTENTS Welcomes 4 7th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel 8 7th AACTA International Awards 12 Longford Lyell Award 16 Trailblazer Award 18 Byron Kennedy Award 20 Asia International Engagement Program 22 2017 Member Events Program Highlights 27 2018 Member Events Program 29 AACTA TV 32 #SocialShorts 34 Meet the Nominees presented by AFTRS 36 Social Media Highlights 38 In Memoriam 40 Winners and Nominees 42 7th AACTA Awards Jurors 46 Acknowledgements 47 Partners 48 Publisher Australian Film Institute | Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Design and Layout Bradley Arden Print Partner Kwik Kopy Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. The publisher does not accept liability for errors or omissions. Similarly, every effort has been made to obtain permission from the copyright holders for material that appears in this publication. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Comments and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of AFI | AACTA, which accepts no responsibility for these comments and opinions. This collection © Copyright 2018 AFI | AACTA and individual contributors. Front Cover, top right: Nicole Kidman accepting the AACTA Awards for Best Supporting Actress (Lion) and Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama (Top Of The Lake: China Girl). Bottom Celia Pacquola accepting the AACTA Award for Best right: Gary Oldman accepting the AACTA International Award for Performance in a Television Comedy (Rosehaven). Best Lead Actor (Darkest Hour). YEAR IN REVIEW WELCOMES 2017 was an incredibly strong year for the Australian Academy and for the Australian screen industry at large. -

Consummate-Love of Evelyn Salt in Philip Noyce's Salt Movie (2010): a Psychoanalytic Approach

CONSUMMATE-LOVE OF EVELYN SALT IN PHILIP NOYCE’S SALT MOVIE (2010): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLES Submitted As a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department Proposed by: ARUM DWI HASTUTININGSIH A320080135 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2012 2 CONSUMMATE-LOVE OF EVELYN SALT IN PHILIP NOYCE’S SALT MOVIE (2010): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH. Arum Dwi Hastutiningsih (Student) Dr. Phil. Dewi Chandraningrum, M.Ed. (Consultant I) Titis Setyabudi, S.S., M. Hum. (Consultant II) (School of Teacher Training and Education, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta) [email protected] ABSTRACT The problem statement of this study is How Consummate-Love of Evelyn Salt influences her personality in Phylip Noyce’s SALT movie. The object of the research is the movie entitled SALT, directed by Phylip Noyce published in 2010. The researcher uses Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory. The writer uses the primary data source is SALT movie itself and the secondary data is the other source related to the analysis such as the author biography, books of literary theory and also psychological books, particularly related to the Psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud. The method of the data collection is library research. The technique of the data analysis is descriptive analysis. From the result analysis, it can be drawn by some conclusions. Firstly, the element of the movie present a good unity. It consists of exposition, complication, climax and resolution. Secondly, the consummate-love of Evelyn Salt influences her to do something under her sense. As the work Ego, Evelyn fulfills the Id demand. -

DREAMWORKS SKG Presenta

DREAMWORKS SKG presenta Diretto da JOHN STEVENSON e MARK OSBORNE Musiche di HANS ZIMMER e JOHN POWELL Soggetto di ETHAN REIFF e CYRUS VORIS Sceneggiatura di JONATHAN AIBEL e GLENN BERGER Coprodotto da JONATHAN AIBEL e GLENN BERGER Produttore Esecutivo BILL DAMASCHKE Prodotto da MELISSA COBB Uscita 29 Agosto 2008 Durata: 92 minuti www.kungfupanda-ilfilm.it “Kung Fu Panda” Note di Produzione 2 Sinossi Grande, vivace e un po’ maldestro, Po (Jack Black, nominato al Golden Globe) è il fan di kung fu più sfegatato che si sia mai visto…e la cosa potrebbe non essere molto adatta a chi deve lavorare tutti i giorni nel negozio di spaghetti della sua famiglia. Improvvisamente chiamato ad esaudire un’antica profezia, i sogni di Po si avverano e il piccolo panda entra a far parte del mondo del kung fu per allenarsi al fianco dei suoi idoli, i leggendari Cinque Cicloni: Tigre (l’attrice premio Oscar® Angelina Jolie); Gru (attore vincitore di un Emmy Award, David Cross); Mantide (Seth Rogen, nominato all’Emmy); Vipera (Lucy Liu, nominata all’Emmy e al SAG Award); e Scimmia (superstar internazionale Jackie Chan), e il loro guru, il Maestro Shifu (Dustin Hoffman, due volte premio Oscar®). Ma prima che possano rendersene conto, il vendicativo e traditore leopardo delle nevi Tai Lung (Ian McShane, premiato con l’Emmy e il Golden Globe) ne fiuta le tracce, e toccherà a Po difendere tutti dall’incombente minaccia. Riuscirà il piccolo panda a diventare un vero maestro di kung fu? Po ci metterà il cuore, e l’improbabile eroe alla fine scoprirà che le sue maggiori debolezze possono diventare un grande punto di forza.