Rory Ellinger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maneaterdaily-2016-02-22-To-2016-02-28.Pdf (718.0Kb)

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS A daily rundown of news at the University of Missouri, presented View this email in your by Mizzou Student Media. browser Monday, February 22, 2016 Today's Weather Remember that beautiful weekend? Cherish those memories. It will be partly cloudy with a high of 53 degrees and a low of 33. Have You Heard? Two years, no progress: Revisiting the University Village collapse On-campus child care and affordable university-sponsored housing options have long been demanded by graduate students. The conversation gained momentum when, two years ago, a walkway at the University Village student housing complex collapsed, killing Columbia firefighter Lt. Bruce Britt. On the anniversary of his death, we look at what progress has been made. Slate drops out of Residence Halls Association presidential election A little over a week after the slates for the upcoming RHA election were announced, one of the two slates dropped out. Voting is set to start March 2, but the RHA justices don’t want Matt Bourke and Martha Pangborn to win by default. So now voters will be able to select either the Bourke/Pangborn slate or no confidence. How do you like them odds? Office of Civil Rights and Title IX investigates vulgar email One MU sophomore has apologized after a rather graphic email he sent about the women of Pi Beta Phi was leaked on social media. Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Cathy Scroggs called it disgusting, and Panhellenic Association executive board said it challenged the role of women in the Greek community. For more news, see our top stories Let's dig a little deeper The University Village walkway collapsed two years ago today. -

Jaya Ghosh 510 High Street, Apt 220 (573) 953-0775 Columbia, MO 65201 [email protected]

Jaya Ghosh 510 High Street, Apt 220 (573) 953-0775 Columbia, MO 65201 [email protected] Highly motivated, focused and experienced leader offering entrepreneurial and technical expertise to expand the breadth of our biomedical technologies, and unifying diverse groups to achieve common goals. Resourceful and forward-thinking professional capable of managing personnel and processes, identifying needs, implementing improvements, and communicating in an efficient manner. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE University of Missouri, Columbia, MO July 2015-Present Program Director, MU-Coulter Biomedical Accelerator January 2019-Present Assistant Program Director, MU-Coulter Biomedical Accelerator July 2015-December 2018 • Promoted to Program Director to lead and manage all program processes and activities, market the program, develop overall program annual budget and oversee program expenditures • Manage and improve all processes associated with proposal solicitation, review, project selection and reporting • De-risk proposed projects in aspects such as intellectual property and market opportunity, identify and engage early with potential partners with financing and product development capabilities, and then fund specific determinative experiments in a disciplined, managed process • Work with Project Investigators to track the progress of all funded projects against project milestones on a bi-monthly basis and communicate the progress and/or changes to the project timeline to all stakeholders • Work with the Office of Technology Management and Industry -

The Maneater Daily: Marches and Wiretappin

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS The Maneater Daily View this email in your browser Monday, January 30, 2017 The weekend’s warm weather continues into the week. Today’s high will be 55 degrees, and the low will be 35. It’ll be partly cloudy throughout the day. University of Missouri professor Melissa Stormont lays flowers on the steps of the Islamic Center of Central Missouri. | Lane Burdette/Photographer Local citizens hold solidarity march in Columbia in response to Trump's "Muslim ban" President Donald Trump signed an executive order Friday that limits the immigration from seven majority Muslim countries. The rally started in Peace Park to stand with local Muslims. A representative of the Islamic Center of Central Missouri led about 200 people from the park to the mosque at the corner of Fifth and Locust streets, where they were greeted with cookies, snacks and juice. The marchers left their signs and flowers on the front steps of the mosque and then returned to Peace Park. CPD faces allegations of illegally recording client-attorney calls The complaint was filed against the Columbia Police Department by attorney Stephen Wyse on Jan. 23. Wyse filed the complaint after he read about a drunk driving case in the Columbia Daily Tribune, in which cops violated attorney-client privilege by covertly observing and recording the conversation. Federal law makes it illegal to intentionally intercept, disclose or use any wire, oral or electronic communication through the use of a “device,” and law enforcement officers may only wiretap a conversation in which one of the parties involved in the conversation has consented to the recording. -

MU-Map-0118-Booklet.Pdf (7.205Mb)

visitors guide 2016–17 EVEN WHEN THEY’RE AWAY, MAKE IT FEEL LIKE HOME WHEN YOU STAY! welcome Stoney Creek Hotel and Conference Center is the perfect place to stay when you come to visit the MU Campus. With lodge-like amenities and accommodations, you’ll experience a stay that will feel and look like home. Enjoy our beautifully designed guest rooms, complimentary to mizzou! wi-f and hot breakfast. We look forward to your stay at Stoney Creek Hotel & Conference Center! FOOD AND DRINK LOCAL STOPS table of contents 18 Touring campus works up 30 Just outside of campus, an appetite. there's still more to do and see in mid-Missouri. CAMPUS SIGHTS SHOPPING 2 Hit the highlights of Mizzou’s 24 Downtown CoMo is a great BUSINESS INDEX scenic campus. place to buy that perfect gift. 32 SPIRIT ENTERTAINMENT MIZZOU CONTACTS 12 Catch a game at Mizzou’s 27 Whether audio, visual or both, 33 Phone numbers and websites top-notch athletics facilities. Columbia’s venues are memorable. to answer all your Mizzou-related questions. CAMPUS MAP FESTIVALS Find your way around Come back and visit during 16 29 our main campus. one of Columbia’s signature festivals. The 2016–17 MU Visitors Guide is produced by Mizzou Creative for the Ofce of Visitor Relations, 104 Jesse Hall, 2601 S. Providence Rd. Columbia, MO | 573.442.6400 | StoneyCreekHotels.com Columbia, MO 65211, 800-856-2181. To view a digital version of this guide, visit missouri.edu/visitors. To advertise in next year’s edition, contact Scott Reeter, 573-882-7358, [email protected]. -

The Maneater Daily

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS The Maneater Daily View this email in your browser Monday, February 6, 2017 Yesterday’s warm weather continues today, with a high of 57 degrees and a low of 52. Be sure to pack an umbrella and wear your rain boots, because there will be thunderstorms later in the day. Eric Greitens | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Gov. Eric Greitens withdrew two nominations from the UM Board of Curators, leaving five seats vacant As of the first meeting of the year, the Board of Curators will be down five members out of the usual total of nine members. Gov. Greitens has yet to make his own nominations to fill the open positions. With the withdrawal of the nominations of Jon Sundvold and Patrick Graham, an MU senior, the board loses its student representation. The first meeting will still be held next week in Columbia with two curators — Donald Cupps and Pamela Henrickson — serving past their term expiration. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Recap: THE SUPER BOWL The Falcons opened the game strong against the team everyone loves to hate: the Patriots. By halftime, the score was 21-3 Falcons. The Patriots ended up coming out on top, finishing the game with a score of 34-28. What to Watch: The St. Louis Blues play the Philadelphia Flyers at 6 p.m. on NBCS. Courtesy of YouTube This weekend proved to be jampacked: Melissa McCarthy returned to SNL for a 7-minute sketch as Press Secretary Sean Spicer. The bit spread around the internet like wildfire, especially due to McCarthy’s uncanny resemblance to Spicer. -

2019 - 2020 Resource Guide

2019 - 2020 RESOURCE GUIDE 2019 - 2020 RESOURCE GUIDE Since 1853, the Mizzou Alumni Association has carried the torch of alumni support for the University of Missouri. From our first president, Gen. Odon Guitar, until today we have been blessed with extraordinary volunteer leadership. Thanks in large part to that leadership, the Association has been a proud and prominent resource for the University and its alumni for 165 years. This resource guide is the product of our commitment to communicate efficiently and effectively with our volunteer leaders. We hope the enclosed information is a useful tool for you as you serve on our Governing Board. It is critical that you know and share the story of how the Association proudly serves the best interests and traditions of Missouri’s flagship university. We are proud to serve a worldwide network of 325,000 Mizzou alumni. Your volunteer leadership represents a portion of our diverse, vibrant and loyal membership base. While Mizzou has many cherished traditions, the tradition of alumni support is one that we foster by our actions and commitment to the Association and the University. Thank you for your selfless service to MU and the Association. With your involvement and engagement, I am confident we will reach our vision of becoming the preeminent resource for the University of Missouri. Our staff and I look forward to working with you in 2019 - 2020. Go Mizzou! Todd A. McCubbin, M Ed ‘95 Executive Director Mizzou Alumni Association Photo By Sheila Marushak Table of Contents Table of Contents of -

University of Missouri

Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri University of Missouri A Journal of Undergraduate Writing Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence Lauren Reagan When prospective students first tour the University of Missouri-Columbia’s campus, they are thinking about academic programs, Tiger football, and the incredible recreational center. The last thing that crosses a student’s mind is being in danger, and tour guides are not likely to mention campus violence. When parents bring up safety issues, the emergency call system and campus police force assures them, and the problems Mizzou faces with assault, rape and robbery can be ignored. In accordance with the Clery Act, the University of Missouri must send students emails every time a violent act occurs on campus (Evaluation of Green Dot 777). For most MU students, this is the first they hear of campus danger. Many factors such as gender roles, alcohol use and societal norms lead to violence on Mizzou’s campus. These crimes cause not only physical, but also emotional and mental damage to victims, and students are beginning to protest. The Maneater published an editorial urging students to take a stand against violence, and former MSA president, Xavier Billingsely, sent a mass email in November 2012 urging the same. Current university prevention programs are simply not producing enough results. It is time for students, faculty and community members to change how violence is addressed. http://artifactsjournal.missouri.edu/2013/05/our-home-away-from-home-putting-a-stop-to-college-campus-violence/[9/15/2014 1:13:04 PM] Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri College campuses can be a breeding ground for violence, and a place society expects to be a learning community can become extremely dangerous. -

FY 10 Gov Bd Manual Indd.Indd

On the occasion of the Mizzou Alumni Association’s sesquicentennial, the association asked a researcher to dig up its history. The story is one of loyal alumni and citizens acting on behalf of Mizzou. (Perhaps what says it best is the legend of how alumni and locals saw to it that the Columns became Mizzou’s foremost campus icon.) MU alumni and citizens gather at the base of the Columns in the days after a fi re that destroyed Academic Hall in 1892. Keep your hands off these Columns he Mizzou Alumni Association was founded in 1853, but perhaps the best story that encapsulates its meaning to MU comes from a tenuous time in the University’s history. It’s the story of loyal alumni Tand citizens acting on behalf of Mizzou and how the Alumni Association saw to it that the Columns became Mizzou’s foremost campus icon. The inferno that consumed Academic Hall in 1892 somehow spared the six limestone Columns. To many alumni and Columbians at the time, they quickly became an enduring symbol of all they held dear about the University. But to others, including the University’s Board of Curators, the Columns looked out of scale with the new University buildings they hoped to construct around them. They resolved that the Columns would have to come down. Few people now know – perhaps because it weakens the legend – that the board originally intended to leave the Columns in place or reposition them on campus. But the board changed its mind, and some alumni and locals didn’t like it. -

The Maneater Daily: Stand Your Ground and Ragtag Oscars Movies

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS The Maneater Daily View this email in your browser Monday, February 20, 2017 The weirdly warm weather continues into this week. The high today will be 69 degrees, and the low will be 50. Be sure to pack your umbrellas for early thunderstorms and afternoon rain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons A new "Stand Your Ground" law was cited in a recent Columbia shooting Senate Bill 656, which went into effect Jan. 1, allows citizens to use deadly force whenever they feel reasonably threatened, without retreating first. This is commonly referred to as “Stand Your Ground.” Columbia resident Karl Henson was arrested last month for first-degree felony after shooting at a man who tried to steal his cellphone. “The only reason I thought it was okay to shoot at him while he was running away was because of what happened with the new year on the law change,” Henson said in the probable cause statement for the Jan. 23 incident. Column: It's brutal having someone sit in your unassigned assigned seat Columnist Kennedy Horton tackles the problem we’ve all experienced: someone stealing your unassigned assigned seat. “Determining one’s seat happens in the first two days of class. The rules of a classroom versus a lecture hell are a bit different, because after a certain row in a lecture, it doesn’t matter; it’s just all counted as “the back.” Nevertheless, there are still rules. After two days of class, you should be locked in and solidified. You’re essentially sworn into that seat until the end of time, or at least the semester. -

2016 Front.Indd

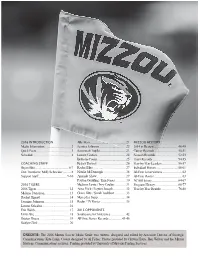

2016 INTRODUCTION Allie Hess ............................................21 MIZZOU HISTORY Media Information .................................2 Jessica Johnson .................................22 2014 in Review ..............................48-49 Quick Facts ...........................................3 Savannah Trujillo ................................23 Career Records .............................50-51 Schedule ............................................... 4 Lauren Gaston ....................................24 Season Records ............................52-53 Bethany Coons ...................................25 Team Records ...............................54-55 COACHING STAFF Kelsey Dossey ....................................26 Year-by-Year Leaders ....................56-57 Bryan Blitz .........................................6-7 Rachel Hise ........................................27 Individual Honors ...........................58-61 Don Trentham / Molly Schneider ..........8 Natalie McDonough ............................38 All-Time Letterwinners ........................62 Support Staff ....................................9-10 Amanda Shaw ....................................29 All-Time Roster ...................................63 Payton Goulding / Erin Jones .............30 NCAA History .................................64-67 2016 TIGERS Madison Lewis / Izzy Coulter ..............31 Program History .............................68-77 2016 Tigers .........................................12 Anna Frick / Peyton Joseph ................32 Year-by-Year -

Mstylebook 2012-13

MSTYLEBOOK 2012-13 INSIDE THe book FIRST EDITION HISTORY Winter 1998 by Editor-in-Chief Jennifer Dlouhy and Managing Editor Kelly Wiese The Maneater stylebook was first printed in February 1998, revised SECOND EDITION by Editor-in-Chief Jennifer Dlouhy and Managing Editor Kelly Wiese. Summer Session 1998 by For this, the 14th edition, revisions were made in Summer 2012 by Editor-in-Chief John Roby Copy Chiefs Tony Puricelli and Katie Yaeger. THIRD EDITION Fall Semester 1999 by Managing Editor Julie Bykowitz INSIDE FOURTH EDITION Winter Semester 2001 by Managing Editor The first portion of the stylebook is dedicated to general policies and Chris Heisel and Copy Chief Kristen Cox administrative guidelines for the newspaper. FIFTH EDITION The second portion is dedicated to entries much like one would find Summer 2002 by Managing in the AP Stylebook. These are guidelines for copy-editing decisions at Editor Stephanie Grasmick SIXTH EDITION The Maneater for the newspaper, MOVE Magazine, themaneater.com Summer 2004 by Copy Chief Amy Rainey and move.themaneater.com. Editors, writers, designers, photographers SEVENTH EDITION and online staff should be familiar with these. Winter 2006 by Copy Chiefs Aaron Richter The third section is geared to accommodate the specific styles of and Sarah Larimer, Managing Editor Coulter cutlines and crime and sports copy. Jones and Editor-in-Chief Jenna Youngs EIGHTH EDITION The fourth section is devoted to style for Arts & Entertainment copy Fall 2006 by Copy Chiefs Jenn Amur and and content for MOVE Magazine. Courtney French, Managing Editor Maggie This is followed by the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Asso- Creamer and Editor-in-Chief Lee Logan ciation supplement of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender terminology. -

2020 Missouri Press Foundation Annual Report 0

2020 Missouri Press Foundation Annual Report 0 MISSOURI PRESS FOUNDATION 2020 Annual Report 2020 Missouri Press Foundation Annual Report 0 MISSOURI PRESS FOUNDATION 2020 Annual Report Preserving the Past Focused on the Future 2020 Missouri Press Foundation Annual Report 1 HIGHLIGHTS FOR OUR STAKEHOLDERS Financial Highlights In 2020, we cancelled several activities to mitigate and prevent the spread of COVID-19, a global pandemic that paradoxically made newspapers more essential while reducing the capacity of people to support them. The most exciting financial news is definitely growth in the Page Builders program. With a new high of 55 Page Builders and an increased match from Missouri Press Services, the Foundation raised almost $55,000 through the donation of ad space and/or the giving of advertising revenue. There are also more than 100 members of the giving Society of 1867, including 14 members who joined for the first time or increased in giving levels last year. Key Performance Indicators The Missouri Press Foundation’s mission is to honor the past, protect the present, and build the future of journalism in general and Missouri newspapers in particular as a vibrant force in a democratic society. The Key Performance Indicators that measure our success are: • Awards and inductions that honor those in the newspaper industry • Summer interns who offer vital energy to Missouri newspapers and acquire vital skills to succeed as journalists going forward • Financial support that helps our industry thrive, including scholarships that make educational opportunities a reality for young journalists • Downloads of our Newspapers in Education activities to increase newspaper information literacy rates among young readers and writers • Participation in events that bring us together to celebrate and collaborate Looking Ahead Early this year, the Foundation was on a continued upward trajectory.