Modernityy Environment, and Society on the Arrow Lakes*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

FAR Area Zip Codes

FAR ZIP State Name 99950 AK Ketchikan 99927 AK Point Baker 99926 AK Metlakatla 99925 AK Klawock 99923 AK Hyder 99922 AK Hydaburg 99921 AK Craig 99919 AK Thorne Bay 99903 AK Meyers Chuck 99840 AK Skagway 99835 AK Sitka 99833 AK Petersburg 99829 AK Hoonah 99827 AK Haines 99826 AK Gustavus 99825 AK Elfin Cove 99824 AK Douglas 99801 AK Juneau 99789 AK Nuiqsut 99788 AK Chalkyitsik 99786 AK Ambler 99785 AK Brevig Mission 99784 AK White Mountain 99783 AK Wales 99782 AK Wainwright 99781 AK Venetie 99780 AK Tok 99778 AK Teller 99777 AK Tanana 99774 AK Stevens Village 99773 AK Shungnak 99772 AK Shishmaref 99771 AK Shaktoolik 99770 AK Selawik 99769 AK Savoonga 99768 AK Ruby 99767 AK Rampart 99766 AK Point Hope 99765 AK Nulato 99763 AK Noorvik 99762 AK Nome 99761 AK Noatak 99759 AK Point Lay 99758 AK Minto 99757 AK Lake Minchumina 99756 AK Manley Hot Springs 99755 AK Denali National Park 99753 AK Koyuk 99752 AK Kotzebue 99751 AK Kobuk 99750 AK Kivalina 99749 AK Kiana 99748 AK Kaltag 99747 AK Kaktovik 99746 AK Huslia 99745 AK Hughes 99744 AK Anderson 99743 AK Healy 99742 AK Gambell 99741 AK Galena 99740 AK Fort Yukon 99739 AK Elim 99737 AK Delta Junction 99736 AK Deering 99734 AK Prudhoe Bay 99733 AK Circle 99730 AK Central 99729 AK Cantwell 99727 AK Buckland 99726 AK Bettles Field 99724 AK Beaver 99723 AK Barrow 99722 AK Arctic Village 99721 AK Anaktuvuk Pass 99720 AK Allakaket 99692 AK Dutch Harbor 99691 AK Nikolai 99689 AK Yakutat 99688 AK Willow 99686 AK Valdez 99685 AK Unalaska 99684 AK Unalakleet 99683 AK Trapper Creek 99682 AK Tyonek 99681 AK -

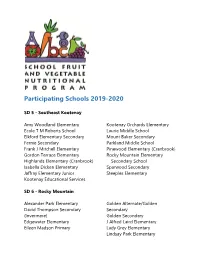

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Brenda Mayson a Very Deserving 2004 Nakusp Citizen of the Year

April 27, 2005 The Valley Voice Volume 14, Number 8 April 27, 2005 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently-owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Brenda Mayson a very deserving 2004 Nakusp Citizen of the Year by Jan McMurray to live, and representatives of the told her story about being Brenda’s moved back, the Dinnings also did, right wind up the evening. All four of her The celebration of Brenda various groups Brenda belongs to. neighbour twice. The first time, Dinning next door to Brenda and Harry. “It was children were there, as well as two Mayson as Nakusp’s Citizen of the Brenda said she was surprised had just moved in and Brenda was at better the second time because Harry nieces and two granddaughters. Year 2004 attracted what several and speechless when she found out the door with a lemon pie. “I was so wasn’t as noisy and the kid finally left,” Susie, Ted’s wife, said that Brenda Rotarians present said was probably she had been named Citizen of the happy to have such a thoughtful she joked. “I hope we’ll be neighbours had been a huge inspiration to her and the biggest crowd the event has ever Year. She thanked all those involved neighbour...but then there was Harry next time, up there,” she said, pointing extended congratulations. Ted said seen. The April 16 banquet and in nominating her, the Rotary Club and Ted,” she lamented jokingly, saying up to heaven. -

ANN ARBOR ARGUS-DEMOCRAT CLOSING THEM out I Money Saving

ANN ARBOR ARGUS-DEMOCRAT VOL. LXVII.—NO 27 ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, JULY 4, 1902. WHOLE NO. 3539 Olivia avenue was badly washed out qnn njTJTTi/triJxnruxnjTjTrinnruxnjTjTjTr^ over its whole extent. HEAVY STORM The road at the corner of Seventh TRAINS THROUGH ANN ARBOR and Madison streets was very l>adly washed out. SCHAIRER & MILLEN A number of people came hi to see E Gentry's circus. The circus got stalled WILL RUN TO PITTSBURG at Chelsea. It was there yet at 11:30 Ann Arbor Loses $5,000 on this forenoon. No trains had come in The Ann Arbor to Become a Part of the Wabash from the west at 3 o'clock this after- Streets and Culverts noon and there had been no western Railroad System CLOSING THEM OUT mails in. It was expected, however, that the east bound trains on the Mich- Suits, Jackets, Walking Ski r STORM KING RAMPANI igan Central would be through shortly The Ann Arbor and Wheeling & Lake Erie to be after 4 this afternoon. Closely Joined—Through Trains Detroit and Silk Waists Cellars of Houses Filled with The cars on the D., Y., A. A. & J. to Toledo Via. Milan Water—Trains Delayed were unable to get past Grass Lake and cars have been run to Chelsea and for Hours backed to Ann Arbor. The theatre car Within the year the Ann Arbor rail- from there to Steubenville, a distance TAILOR MADE SUITS from Detroit last night was held up road is to be made a part of the Wa-of 24 miles. -

Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC

Final Report November 7th 2010 Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC Prepared for the: Fraser Basin Council Kamloops, BC Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC Prepared for the: Fraser Basin Council Kamloops, BC Prepared by: Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. 30 Gostick Place North Vancouver, BC V7M 3G3 Final Report November 7th 2010 Project 35138 DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. in accordance with generally accepted engineering and geoscience practices and is intended for the exclusive use and benefit of the client for whom it was prepared and for the particular purpose for which it was prepared. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made. Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. and its officers, directors, employees, and agents assume no responsibility for the reliance upon this document or any of its contents by any party other than the client for whom the document was prepared. The contents of this document are not to be relied upon or used, in whole or in part, by or for the benefit of others without specific written authorization from Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. and our client. Report prepared by: Ken I. Ashley, Ph.D., Senior Scientist Ken J. Hall, Ph.D. Associate Report reviewed by: Barry Chilibeck, P.Eng. Principal Engineer NHC. 2010. Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan for the Shuswap Lakes, BC. Prepared for the Fraser Basin Council. November 7thth, 2010. © copyright 2010 Shuswap Lake Integrated Water Quality Monitoring Plan i CREDITS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge to Mike Crowe (DFO, Kamloops), Ian McGregor (Ministry of Environment, Kamloops), Phil Hallinan (Fraser Basin Council, Kamloops) and Ray Nadeau (Shuswap Water Action Team Society) for supporting the development of the Shuswap Lakes water quality monitoring plan. -

Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau

LATE PREHISTORIC CULTURAL HORIZONS ON THE CANADIAN PLATEAU Department of Archaeology Thomas H. Richards Simon Fraser University Michael K. Rousseau Publication Number 16 1987 Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Roy L. Carlson (Chairman) Knut R. Fladmark Brian Hayden Philip M. Hobler Jack D. Nance Erie Nelson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 0-86491-077-0 PRINTED IN CANADA The Department of Archaeology publishes papers and monographs which relate to its teaching and research interests. Communications concerning publications should be directed to the Chairman of the Publications Committee. © Copyright 1987 Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau by Thomas H. Richards and Michael K. Rousseau Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Publication Number 16 1987 Burnaby, British Columbia We respectfully dedicate this volume to the memory of CHARLES E. BORDEN (1905-1978) the father of British Columbia archaeology. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................vii List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................iv -

The Valley Voice Is a Locally-Owned Independent Newspaper

February 22, 2012 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 21, Number 4 February 22, 2012 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Ministry slaps suspension on Meadow Creek Cedar’s forest licence by Jan McMurray that the $42,000 fine and the Wiggill also explained that there rather than allowing Meadow Creek for Meadow Creek Cedar. An FPB Meadow Creek Cedar (MCC) remediation order to reforest the is one exception to the company’s Cedar to seize the logs in the bush.” spokesperson reported that the has been given notice that its forest six blocks relate directly to the licence suspension. Operations on He added that if logs are left in the investigation of that complaint is licence is suspended as of February silviculture contravention found in a cutblock in the Trout Lake area, bush too long, there is a vulnerability nearing completion. FPB complaints 29. The company was also given the recent investigation. The decision which include a road permit, will be to spruce budworm. are completely separate from ministry a $42,000 fine for failing to meet to suspend the licence, however, was allowed to continue past the February Wiggill confirmed that some investigations. its silviculture (tree planting) made based on both current and past 29 suspension date. “This is to additional ministry investigations are In addition, many violations of obligations, and an order to have contraventions. essentially protect the interests of the ongoing involving Meadow Creek safety regulations have been found the tree planting done by August 15. -

Slocan Lake 2007 - 2010

BC Lake Stewardship and Monitoring Program Slocan Lake 2007 - 2010 A partnership between the BC Lake Stewardship Society and the Ministry of Environment The Importance of Slocan Lake & its Watershed British Columbians want lakes to provide good water quality, quality of the water resource is largely determined by a water- aesthetics, and recreational opportunities. When these features shed’s capacity to buffer impacts and absorb pollution. are not apparent in our local lakes, people begin to wonder why. Concerns often include whether the water quality is getting Every component of a watershed (vegetation, soil, wildlife, etc.) worse, if the lake has been impacted by land development or has an important function in maintaining good water quality and a other human activities, and what conditions will result from more healthy aquatic environment. It is a common misconception that development within the watershed. detrimental land use practices will not impact water quality if they are kept away from the area immediately surrounding a water- The BC Lake Stewardship Society (BCLSS), in collaboration body. Poor land use practices in a watershed can eventually im- with the Ministry of Environment (MoE), has designed a pro- pact the water quality of the downstream environment. gram, entitled The BC Lake Stewardship and Monitoring Pro- gram, to address these concerns. Through regular water sample Human activities that impact water bodies range from small but collections, we can come to understand a lake's current water widespread and numerous non-point sources throughout the wa- quality, identify the preferred uses for a given lake, and monitor tershed to large point sources of concentrated pollution (e.g. -

Flooding Renata May 1, 2013

Flooding Renata May 1, 2013 Hi Thomas, Thank you for this lovely essay about the 3 Gorges Dam. Where did you find out about it? Did you know that a dam in BC flooded the town in which your Great‐Great‐Granduncle lived? His name was Jacob (like yours), but people called him “Jake”. He and his wife lived in a small town called Renata on the Arrow Lakes of the Kootenay region in BC. They had a farm there with a lovely orchard of apples, cherries, pears, and peaches and a big garden of vegetables and flowers. I remember visiting the town when I was a bit older than you – maybe 14 or 15 years old (about 1958). We slept in an old yellow school bus that they had fixed up like a camper. They used it during the fall for farm workers to live in when they came by for the harvest. I have included a photo of it. I remember finding it strange because it had a side door near the back. Down the road from the farmhouse was an old wharf where a paddlewheeler would dock. They used a paddlewheeler in those days because they had a shallow draft (ask Zachary what that means if you don’t know) so the boat could come in very close to the many shallow spots along the Arrow lakes. The most famous of those sternwheelers was the Minto – pictured here in this photograph. It is docked at the wharf just in front of my Great‐Uncle Jake’s farm. -

RG 42 - Marine Branch

FINDING AID: 42-21 RECORD GROUP: RG 42 - Marine Branch SERIES: C-3 - Register of Wrecks and Casualties, Inland Waters DESCRIPTION: The finding aid is an incomplete list of Statement of Shipping Casualties Resulting in Total Loss. DATE: April 1998 LIST OF SHIPPING CASUALTIES RESULTING IN TOTAL LOSS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA COASTAL WATERS SINCE 1897 Port of Net Date Name of vessel Registry Register Nature of casualty O.N. Tonnage Place of casualty 18 9 7 Dec. - NAKUSP New Westminster, 831,83 Fire, B.C. Arrow Lake, B.C. 18 9 8 June ISKOOT Victoria, B.C. 356 Stranded, near Alaska July 1 MARQUIS OF DUFFERIN Vancouver, B.C. 629 Went to pieces while being towed, 4 miles off Carmanah Point, Vancouver Island, B.C. Sept.16 BARBARA BOSCOWITZ Victoria, B.C. 239 Stranded, Browning Island, Kitkatlah Inlet, B.C. Sept.27 PIONEER Victoria, B.C. 66 Missing, North Pacific Nov. 29 CITY OF AINSWORTH New Westminster, 193 Sprung a leak, B.C. Kootenay Lake, B.C. Nov. 29 STIRINE CHIEF Vancouver, B.C. Vessel parted her chains while being towed, Alaskan waters, North Pacific 18 9 9 Feb. 1 GREENWOOD Victoria, B.C. 89,77 Fire, laid up July 12 LOUISE Seaback, Wash. 167 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. July 12 KATHLEEN Victoria, B.C. 590 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. Sept.10 BON ACCORD New Westminster, 52 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 GLADYS New Westminster, 211 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 EDGAR New Westminster, 114 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. -

2018 General Local Elections

LOCAL ELECTIONS CAMPAIGN FINANCING CANDIDATES 2018 General Local Elections JURISDICTION ELECTION AREA OFFICE EXPENSE LIMIT CANDIDATE NAME FINANCIAL AGENT NAME FINANCIAL AGENT MAILING ADDRESS 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Wally Bramsleven Wally Bramsleven 5538 Park Dr 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Leon Chretien Leon Chretien 6761 McMillan Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Ralph Fossum Ralph Fossum 5648-103 Mile Lake Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Laura Laing Laura Laing 6298 Doman Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Cameron McSorley Cameron McSorley 4481 Chuckwagon Tr PO Box 318 Forest Grove, BC V0K 1M0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 David Mingo David Mingo 6514 Hwy 24 Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Chris Pettman Chris Pettman PO Box 1352 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Maureen Pinkney Maureen Pinkney PO Box 735 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Nicole Weir Nicole Weir PO Box 545 108 Mile Ranch, BC V0K 2Z0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Mitch Campsall Heather Campsall PO Box 865 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Rita Giesbrecht William Robertson 913 Jens St PO Box 494 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Glen Macdonald Glen Macdonald 6007 Walnut Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E3 Abbotsford Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Jaspreet Anand Jaspreet Anand 2941 Southern Cres Abbotsford, BC V2T 5H8 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Bruce Banman Bruce Banman 34129 Heather Dr Abbotsford, BC V2S 1G6 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Les Barkman Les Barkman 3672 Fife Pl Abbotsford, BC V2S 7A8 This information was collected under the authority of the Local Elections Campaign Financing Act and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.